Shot on Good Friday and dead on Saturday: The timing of the assassination made Easter Sunday 1865 a particularly important—and confusing—occasion, as shocked mourners came to church for what should have been a day of rejoicing over both the resurrection of Christ and military victory.

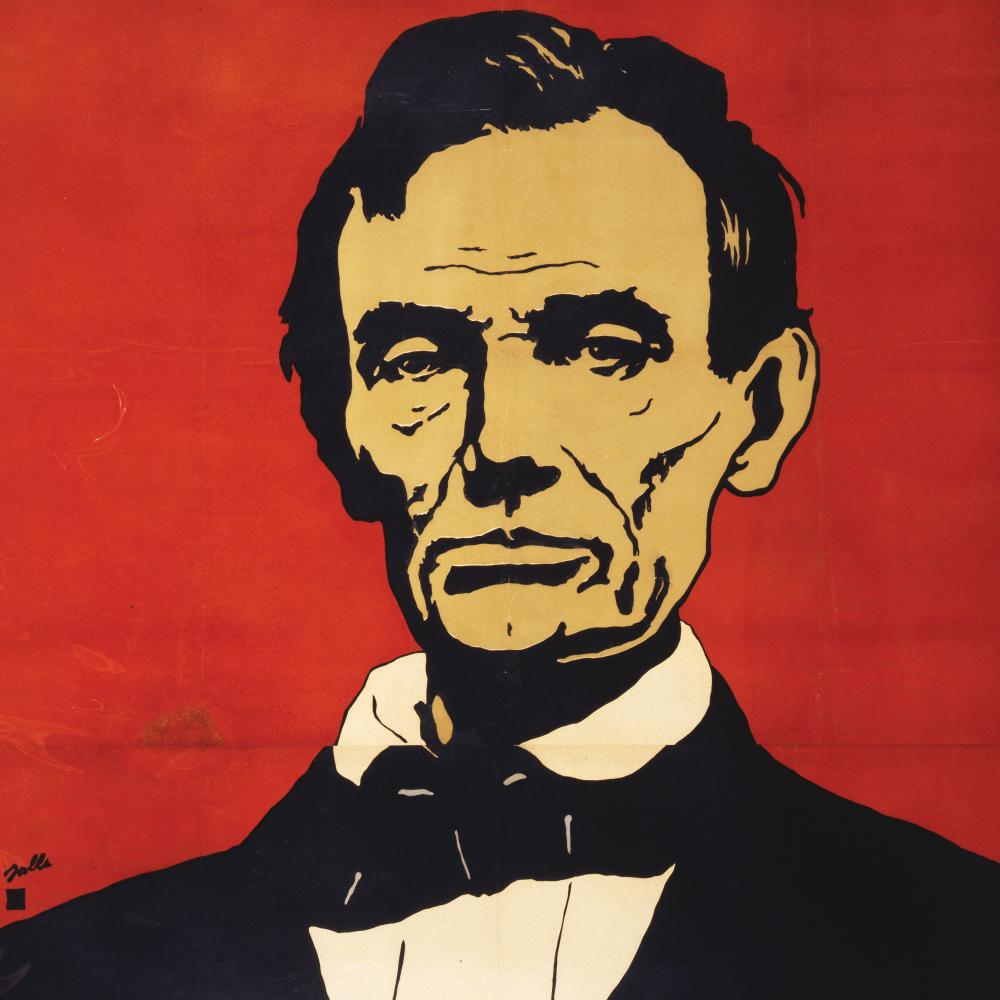

The reversal of fortunes was manifested materially, as churchwomen rearranged the colorful springtime displays they had readied. Easter decoration had become something of a commercial enterprise by the mid nineteenth century, with elaborate presentations meant to reflect religious devotion. Flowers played a central role, and now the women highlighted the white blossoms as they searched for black fabric to cover railings and arches, chancel and altar, pulpit and organ, and placed portraits of the late president amid the myrtle, tea roses, and heliotrope. As a congregant in Boston recorded, grappling with the juxtaposition of joy and sorrow, “This glorious Easter morn our Church put on the garb of mourning.”

The crowds were phenomenal. Pews always filled to capacity on Easter, but no one had ever seen anything like April 16, 1865. Wherever the news had arrived, from the East Coast to the Midwest to the Pacific Ocean, black churches and white churches were jammed. Aisles and galleries were full, choir steps packed tight. Men carried in extra settees and benches, leaving not an inch of floor space to spare. Many who spilled out the doors strained to hear the service, and those at the back of the outdoor crowds stood too far away to hear anything at all. The same was true in army camps, where Union officers and soldiers gathered in unprecedented numbers to listen to whoever was preaching and however many sermons were offered. The same as the day before, mourners craved company in order to absorb the tragic event. The shock had not yet dissipated, and just as in the streets on Saturday, on Sunday people observed the grief of their neighbors in church or their comrades in camp, reading the faces around them for confirmation that it was not, after all, a hoax or a dream.

Very sad: Those two words conveyed the heavy sorrow that had mixed with the initial shock from the first moment Lincoln’s supporters had counted the news as credible. In Baton Rouge, a Union army chaplain found the hundreds of freedpeople “all very sad.” In Minnesota, “the people all feel very sad,” a soldier wrote in his diary. It was, Mary Emerson wrote from Paris, in her petit souvenir journalier, the “saddest saddest news we ever heard.” Others employed more vivid vocabulary. The news “threw a mantle of sadness over every heart,” or people were “struck down” in anguish, “crest fallen and agitated.” One soldier thought even the defeat of Sherman or Grant would have brought less gloom to camp. Just as mourners had draped their churches, so too did they imagine nature attired in grief. Where it rained, people saw the clouds “weeping copiously,” where skies were blue, “the very sunshine looked mournful.” A former slave in Washington said that even the trees were weeping for Lincoln.

For communities of freedpeople across the South, grief washed through like a tidal wave. From Norfolk and Portsmouth, Beaufort and Charleston came the most “heartfelt sorrow,” “troubled countenances,” and “very great” grief. Everywhere children cried audibly and grown-ups wept bitterly. Some cried all night, others just felt numb. One woman described herself as “nearly deranged” with grief. Black soldiers were utterly bereft. Edgar Dinsmore of the 54th Massachusetts felt “a loss irreparable.” One man compared the circumstances to a horrific scene he had witnessed as a slave: a mother whipped forty lashes for weeping when white people took away her children. The violence had traumatized him, “but not half so much as the death of President Lincoln,” he confessed. Some white officers in black regiments felt the sense of loss magnified. “Oh how Sad, How Melancholy,” James Moore wrote to his wife. Such intense sorrow overcame him that it seemed “an impossibility to rally from it.” In Petersburg, Thomas Morris Chester saw both “unfeigned grief” and an “undisguised feeling of horror,” for the question hadn’t gone away: Would they “have to be slaves again”?

African Americans claimed for themselves a special place in the outpouring of sorrow, and the prayers and sermons of Easter Sunday magnified Lincoln’s role as the Great Emancipator. A New Orleans minister asserted that his people felt “deeper sorrow for the friend of the colored man,” and black clergymen in the North allowed that their people felt the loss “more keenly” and “more than all others.” Journalists singled out the “dusky-skinned men of our own race” as the “chief—the truest mourners,” and black soldiers maintained that “as a people none could deplore his loss more than we.” Frederick Douglass, speaking extemporaneously in Rochester on Saturday, told the overflowing crowd that he felt the loss “as a personal as well as national calamity” because of “the race to which I belong.” Even the most stricken white mourners conceded the point. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles thought the “colored people” to be the “truer mourners.” In the words of one minister, “We who are white know little of the emotions which thrill the black man’s heart to-day,” and as another told his congregation, “intense as is our grief,” no white person could “fathom the sorrow” of black people. White mourners also pondered this difference in their personal writings. “How I pity the poor colored people,” wrote one, “who share perhaps most deeply in our great calamity!”

From the moment the news arrived, Lincoln’s mourners cried as they recorded their emotions, smudging the ink in their journals and letters. Up Broadway in New York, with black drapery obscuring all facades, everything “looked so—sorrowful—& sad,” Emily Watkins wrote haltingly to her husband, her dashes perhaps standing in for intermittent sobs. In a small town in Indiana, a young southern Unionist likewise drew dashes (and comforted herself with imagined universality): “The horror and the sorrow are intense—Tears are in all eyes—sobs in every voice—old men and children—rich and poor, white and black.” By the rules of American culture (which applied most strictly to the middle and upper classes), expressions of grief were meant to be properly bounded: too much, and one was overly self-indulgent; too little, and one was not quite sensitive enough. Still, the antebellum decades had witnessed a new sentimentalization of death, as the harshness of the Puritan legacy crumbled, and communities and families increasingly attended to the emotions of earthly survivors. On this particular day, all societal pressure lost its power, and most mourners made little effort to conceal their feelings. For the second day in a row, men wept openly, including clergymen. One minister “broke down & the tears rolled down his cheeks.” Children saw their male Sunday school teachers barely able to get through a prayer. “Even the boys,” Anna Lowell wrote, appeared stricken through the hymns.

Finding words to speak aloud or write down could be a challenge. Frederick Douglass, who had met President Lincoln for the third time only weeks earlier, had “scarcely been able to say a word” to friends who had grasped his hands and looked into his eyes. A black soldier in Florida saw sorrow and misery on every face, yet still “none could express their feelings.” Silence, allowed another black mourner in the South, was the “sure sign of sorrow, and when the heart is full it is difficult to speak.” The same was true for white mourners. After recording facts and details, many stumbled in their attempts to articulate their sentiments on paper. “I cannot express my feelings” and “I cannot describe my feelings” became common refrains for men and women alike. Some conveyed the point more poetically. A Philadelphia man felt a “dull & stupefied sense of calamity.” The British writer Edward Peacock found himself stymied, since any description of genuine emotion would appear “wildly exaggerated.”

Others couldn’t write anything at all. “I have heard such dreadful news today that I feel totally unfit for writing a letter,” a Massachusetts woman confessed to her mother. From the battlefront, General Carl Schurz explained to his wife that he would have written earlier had he been able to “shake off the gloom.” At the same time, those who routinely committed but few words to paper betrayed their sorrow by writing more than usual. Whereas Unitarian minister George Ellis normally kept a bare roster of church doings and dining companions, he now added two descriptive words to his log: “awful consternation.” The perfunctory journal of Elizabeth Childs, usually home to memos like “Fanny dined here,” now carried the notation, “Sad day.”

Complete listlessness could take over from the inability to speak or write. “Do not feel like doing anything,” wrote sixteen-year-old Margaret Howell in Philadelphia (she then crossed out the word thing, and changed it to “work or sewing”). For a Union soldier in Alabama, the news made him feel “so bad,” he told his wife, “that I went to bed and I have not felt like getting up since.” For others, it was just the opposite. “Sleep was out of the question!” wrote a disconsolate English woman. Grief affected people’s physical well-being too, in all kinds of ways: lightheadedness or debilitating headaches, prolonged trembling, “prostration of the nervous system,” even days of indefinable sickness. The declaration of victory had enabled Moses Cleveland, serving outside Mobile, to bear his poor health more easily, but the assassination brought him back to the army surgeon, who dispensed medicine and orders to rest. Henry Gawthrop’s body reacted the other way around; suffering in a Virginia field hospital with an amputated foot and a bleeding stomach, he found that the terrible tidings made him “almost forget bodily pain.” From the start of the ordeal, from the first moments the shock began to wear away to reveal the truth of President Lincoln’s murder, in rushed overwhelming sorrow.

Excerpted from Mourning Lincoln by Martha Hodes, published 2015 by Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.