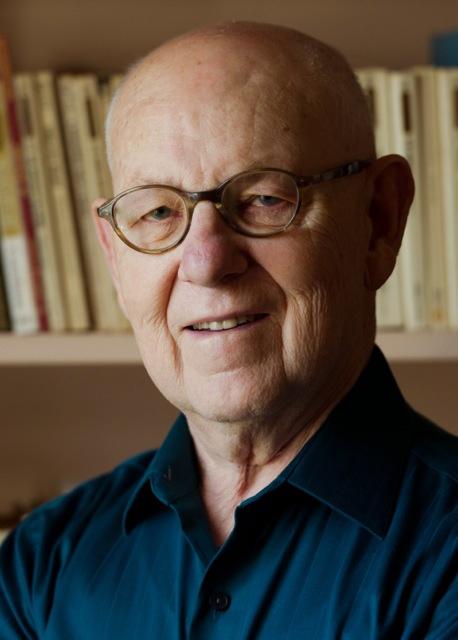

For this edition of IQ, we’re spreading the Gospel, building churches, and meeting monks. In his new book, The First Thousand Years: A Global History of Christianity, Robert Louis Wilken follows Christianity as it developed from a small following into a political and spiritual powerhouse. Wilken, the William R. Kenan Professor of the History of Christianity Emeritus at the University of Virginia, used an NEH fellowship early in his career to research the growth of Christianity in Palestine during the Byzantine Period.

You describe Jesus as a sage and not a philosopher. What do you see as the difference?

No metaphysics or epistemology in the sayings of Jesus. He spoke about real things that people care about: how to get along with family, neighbors, and friends, about anxiety and fear, about faithfulness, love, generosity, and forgiveness. He taught that what delights our frail hearts brings little real satisfaction. The “ideas” are few, but the examples—the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son—are one of the reasons so many of his stories are remembered.

When and where was the term “Christian” first used?

In Antioch in greater Syria sometime about 40 CE.

Early church figure that you don’t think gets enough love from historians?

Eusebius, bishop in Caesarea on the coast of Palestine (north of present-day Tel Aviv) and the first historian of Christianity. His book, covering people and events of the first four centuries, is an indispensable source even today, because he quotes many ancient writings that are no longer extant. But he writes with a distinctive slant that makes it difficult to sort out what is reliable and what is opinion, and he uncritically celebrates the reign of the first Christian emperor Constantine. Even so, it would be hard to write a history of the first three centuries without his Ecclesiastical History.

When did Christians first start thinking of Jerusalem as the “holy land”?

In the fifth century in Palestine. By that time the number of Christians in the ancient land of Israel was mounting and Christian churches were being built all over the country. Christians began to think of the region as a Christian land, and it became a place where Christian life and culture blossomed. Jerusalem, because it was the place where Christ died and rose again,was revered as the premier Christian city. There one could touch with the fingertips the places where Jesus walked and kiss the wood of the cross on which he died.

How was monasticism integral to the development of early Christianity?

There was an ascetic strain in Christianity from the beginning. Paul was not married and Jesus spoke of becoming “eunuchs” for the sake of the kingdom of God. Already in the second century, men and women seeking a way to devote themselves more fully to God stepped out of conventional roles within society to live a solitary life. Monachos, from which we get monasticism, means solitary. As the number of Christians grew, the solitary men and women gave the Christian world models of radical devotion to God.

Favorite monk?

There are so many to choose from. Symeon of Stylite spent decades perched atop a pillar more than twenty feet off the ground. Antony went into the Egyptian desert to live alone and many adopted his way of life. Euthymius came from Armenia, because he wanted to live near the holy city of Jerusalem. Benedict wrote a discerning little book on the life of a monastic community that displays a spirit of moderation and a keen understanding of human nature. What most endears me to the monks is their wisdom.

Some of the sayings of John, a monk in Gaza, remind one of advice columns in the daily newspaper. He was once asked: “If someone is not actually criticizing another person but is gladly listening to criticism, is he also condemned for that?” To which he replied: “Even listening gladly to criticism is criticism.”

At the end of the first century CE, there were fewer than ten thousand Christians in the Roman Empire. By 300 CE, there were six million. Why the huge growth?

We don’t really know. The simple and most reasonable answer was that Christ was unlike any other holy man in the ancient world. As the decades passed, the story of his life, his simple teachings, his miracles, his quiet suffering—making no defense when accused—and, of course, his resurrection from the dead, won the hearts and minds of people from every walk of life.

The church had a knack for attracting leading thinkers to its fold, but you put Augustine above them all. What makes him so special?

He was the most intelligent man in the world. He was a seductive stylist and his sentences captivate the reader. His feelings ran deep and the pages of his books and his letters reveal a man made of flesh not marble. In reading Augustine, it is hard to keep one’s distance. His words soar off the page to sink into the soul of the reader, moving the affections as well as stirring the intellect.

I was surprised to learn that the church had made it all the way to China in the eighth century. What fueled its spread East?

There was a large Syriac-speaking church in Persia (the Sasanian empire, present-day Iraq and Iran), what is today known as the Church of the East. From there, Syriac-speaking missionaries were sent to central Asia, India, China, and perhaps even to Tibet. The most energetic promoter of the mission to the East was Timothy I, the patriarch or catholicos of the Church of the East in Baghdad in the eighth century.

Favorite archive?

The Library of Congress. It is, of course, much more than an archive. We moved to Washington, D.C., ten years ago, and it was serendipitous that we bought a house not too far from the Library of Congress. So much of the research for this book was done in the magnificent domed main reading room.