When Library of America published a collection of Pauline Kael’s film writing last year, many of Kael’s admirers fondly recalled her as the first writer to elevate film criticism to literature. But that distinction actually belongs to an earlier LOA author, James Agee.

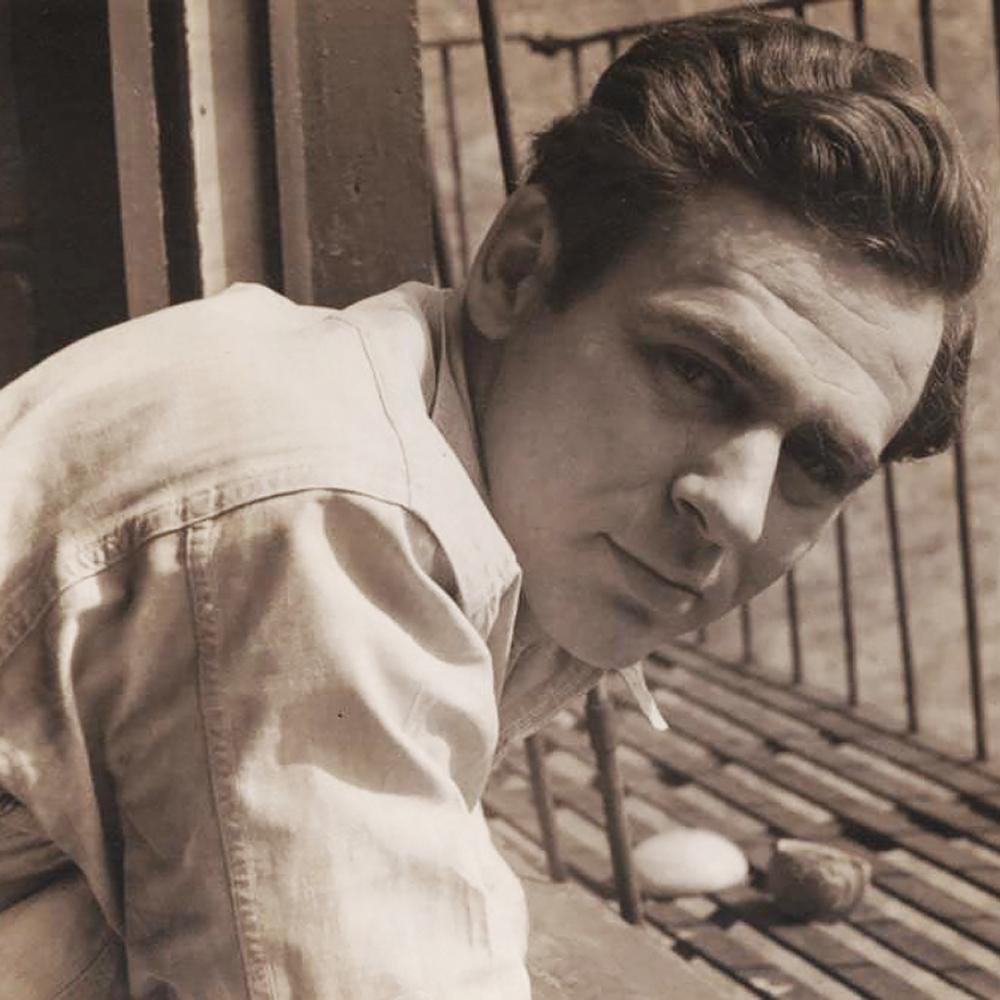

In 1942, a generation before Kael gained fame for her New Yorker reviews, Agee (pronounced Ay-jee) signed on as a movie critic for both Time and the Nation, penning reviews often more memorable than the movies that inspired them. The Agee style—intensely literary and endlessly alert to the textual nuances of an emerging medium—was a striking departure from the prevailing movie coverage, which often seemed little more than a willing arm of the studio publicity mill. When Agee died in 1955 at the age of forty-five, fans of his film work immediately began clamoring for a book that would preserve his best reviews within covers, and Agee on Film appeared in 1958. The book’s publication affirmed the stature of film criticism as its own art form, creating a standard that subsequent generations of reviewers have tried to match.

Decades after Agee’s passing, the idea of film reviewing as something intellectually valuable seems thoroughly mainstream. But when Agee was making his way as a journalist in the 1930s and 1940s, few editors were interested in devoting “think pieces” to something so seemingly transient as a Hollywood flick. In fighting for film’s place in the pantheon of modern culture, Agee was defying convention, even at the risk of stalling his career.

In his other writing projects as well, Agee was reliably rebellious. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, his almost maddeningly obscure account of life among Depression-era Alabama sharecroppers, was a commercial flop when it was released in 1941, although the book now stands as a landmark piece of social documentary. Far more accessible, but no less visionary, is Agee’s most popular book, the posthumously published and largely autobiographical novel A Death in the Family. The current vogue in memoirs about loss, such as Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking and Joyce Carol Oates’s A Widow’s Story, extends a tradition greatly popularized by Agee’s 1957 roman à clef, which uses beautifully poetic prose to recall how the sudden death of Agee’s father radically altered his family’s future.

In addition to reviewing films, Agee was also a groundbreaking screenwriter, adapting Davis Grubb’s novel The Night of the Hunter into the vividly creepy 1955 movie of the same name, and also helping to adapt C. S. Forester’s novel The African Queen into the 1951 film classic.

The Library of America’s collection of Agee’s work spans two volumes: Agee: Film Writing and Selected Journalism and Agee: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, A Death in the Family, and Shorter Fiction.

As a critic of films—and an occasional writer on movie projects—Agee favored productions that seemed to indulge intuition and surprise rather than careful calculation. “Movies are made for respectable people now,” he lamented in 1950. “(They) were better when made for lowbrows and made with instinct and delight.”

If Agee liked to think of the world cinematically, it’s possibly because his life, so touched by deep tragedy, soaring success, and wretched excess, often seemed like a movie in itself.

James Rufus Agee was born on November 27, 1909, in Knoxville, Tennessee, the son of a working-class father and a mother with a more socially connected background. The contrast informed Agee’s view of the world throughout his life. Later, despite a résumé that included a Harvard degree and positions at the top of national journalism, Agee retained a populist sympathy for the have-nots, embracing an aggressive brand of liberalism that sometimes compromised his professional aspirations.

When Agee was only six years old, his father died in a car accident, leaving an absence that would intensely haunt him the rest of his life. Not long after the loss, Agee was sent to an Episcopal boarding school in Sewanee, Tennessee, where he developed an enduring friendship with Father James Harold Flye, a sensitive and intellectual cleric who became Agee’s surrogate father. When he was sixteen, Agee was sent to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, an elite boarding school that proved a culture clash for the unconventional teen.

“He was a Southern boy of a complex background, already in his own way a populist, an earthy, crunchy, idiosyncratic, rebellious—very rebellious—young man,” writes Robert Coles, a prominent social thinker and Agee admirer. “He arrived at the staid New England private school at a time when it was much stiffer and more exclusionary, almost exclusively populated by wealthy East Coast scions of privilege.”

Shortly after his arrival at Exeter, Agee began an affair with a forty-year-old librarian, the early chapter of a libertine sex life that would, by the time of his death, include three marriages and several extramarital relationships. By his high school years, Agee was also a heavy drinker and smoker, two habits that further complicated his personal life and almost certainly shortened it.

Along with his darker tendencies, Agee’s gifts as a writer were emerging, too, as he led the school’s magazine and literary society and churned out a steady stream of stories, criticism, and poetry. The movies had also captured young Agee’s attention, a passion he confessed to Exeter alumnus and Yale undergraduate Dwight Macdonald. “To me, the great thing about movies,” Agee told Macdonald in 1927, “is that it’s a brand new field. I don’t see how much more can be done with writing or the stage. In fact, every kind of recognized ‘art’ has been worked pretty nearly to the limit. Of course, great things will be done in all of them, but, possibly excepting music, I don’t see how they can avoid being at least in part imitations. As for the movies, however, their possibilities are infinite.”

Although he was an indifferent student, Agee’s writing talent secured him strong recommendations for admission to Harvard, where he continued to refine his literary technique. Ever the experimentalist, Agee told Flye that he aspired “to combine what Chekhov did with what Shakespeare did—that is, to move from the dim, rather eventless beauty of (Chekhov) to huge, geometric plots such as Lear . . . I’ve thought of inventing a sort of amphibious style—prose that would run into poetry when the occasion demanded poetic expression.”

In a more casual mood, Agee penned a parody of Time magazine that would be followed, ironically enough, by a postgraduation job working for Time publisher Henry Luce, who hired Agee to work on a sister publication, Fortune. Bohemian and left of center, Agee seemed an odd fit for the staff of a business publication created by Luce, the conservative publisher. But over the years, Luce would bring a number of liberal writers into his stable, including Macdonald, Archibald MacLeish, and Keynesian economist John Kenneth Galbraith. Despite the political divide within the office, Luce benefited from the talent he had assembled, and his writers, in turn, enjoyed well-paying positions. In 1932, when Agee started at Fortune, the economic downturn had made such jobs an especially coveted prize.

Staff writers also stood to benefit from Luce’s deft editorial pen, Galbraith would recall many years later in a fond remembrance of his days at Fortune. “No one who worked for him ever again escaped the feeling that he was there looking over one’s shoulder,” Galbraith remembered. “In his hand was a pencil; down on each page one could expect, any moment, a long swishing wiggle accompanied by the comment: ‘This can go.’ Invariably it could. It was written to please the author and not the reader.”

Agee, though, was more resistant to editorial direction—and, it seemed, direction of any kind. Macdonald would later recall Agee’s tense sessions with Luce, in which Luce attempted, often in vain, to temper Agee’s prolix narratives. At one point, an exasperated Agee fantasized about shooting Luce.

Beyond issues of editorial judgment, Agee proved, in countless other ways, to be a decidedly unconventional Luce employee. “As Luce and his magazine were moving into the Chrysler Building in midtown Manhattan,” Coles writes, “the legend of James Agee was becoming known to the literary community of Manhattan: the enormously talented writer who drank a lot, slept around, and who would write while listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony so loudly and so often that people worried whether the Chrysler Building would withstand the orchestral blasts.”

But the odd-couple relationship between Agee and his publisher, whatever its limitations, coincided with what was perhaps Agee’s most fruitful period as a writer. For Fortune, Agee wrote pieces on everything from orchids to the Tennessee Valley Authority. In the bargain between Agee’s poetic largesse and the more practical sensibility of Luce’s house style, one can find magazine journalism that, like the newspaper reportage of Charles Dickens, crackles with the wry intensity of literary ambition.

Here’s how Agee opens his 1934 Fortune piece on cockfighting:

You are a gentleman. You have a taste for sport (most likely horses), leisure to indulge it, and an estate. One quiet morning you walk down to your stables. As you come around the side of the barn, you hear a soft but violent fluttering of wings, an agitated hissing, a passionate exclaiming of low voices. You look down, and there are your Negroes (if you happen to be a southern gentleman) crouched in a wide circle on the ground, leaning on bent knuckles, peering into the center of the ring. They are watching two birds, large and brightly colored, that cling together beak to beak with arched necks, dancing up and down, while their wings whir and they slash at each other viciously, rapidly, with their spurs. The birds are gamecocks, most ferocious of all domestic creatures, and their dance is fatal—it can end only in death.

Notice how, even within the compass of a magazine article, Agee is already polishing his skills as a screenwriter. The opening sounds like stage direction, followed by a plot synopsis, as if Agee is writing

a pitch for a movie project.

To read Agee is to be reminded that he thought in pictures, which is why, one gathers, he was such a perceptive movie critic. His review

of The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, from 1944, promises to be around longer than the movie itself. “The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek,” he begins,

is a little like taking a nun on a roller coaster. Its ordinary enough subject—the difficulties of a small-town girl, pregnant, without a husband—is treated with the catnip giddiness to be expected from Writer-Director Preston Sturges. . . . The chief failures are his, too. Some of the fun is painfully unfunny, because it is like a joker who outroars his audience’s reaction. Some of the pity is not pitiful because it is smashed before it has a chance to crystallize. Most of the finest human and comic potentialities of the story are lost because Sturges is so much less interested in his characters than in using them as hobbyhorses for his own wit.

Agee was an early enthusiast of Alfred Hitchcock, praising Hitchcock’s 1944 movie, Lifeboat, as “one of the most ambitious films in years,” and comparing it to the poetry of E. E. Cummings. He was also a friend and champion of Charlie Chaplin, lionizing Chaplin and other silent-era comics in a lengthy retrospective for Life in 1949. Agee persuasively affirmed the value of Chaplin and his contemporary comic screen actors, even as the talkies were nudging their legacies into the background.

As Agee progressed in film reviewing, influential readers took notice. Among his admirers was the poet W. H. Auden, who wrote a glowing fan letter to the Nation in 1944. “In my opinion, his column is the most remarkable event in American journalism today,” Auden said of Agee. “What he says is of such profound interest, expressed with such extraordinary wit and felicity, and so transcends its ostensible—to me, rather unimportant—subject, that his articles belong in that very select class—the music critiques of Berlioz and Shaw are the only other members I know—of newspaper work which has permanent literary value.”

In literature as in film, Agee consistently favored artists who took risks, even if it made them less accessible to the public at large. In the book reviews he filed for Time, Agee’s heart quickened when he read writers who embraced experiment: Aldous Huxley, William Faulkner, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf.

Agee’s most audacious attempt at avant-garde expression involved his assignment by Fortune in 1936 to write a story about the struggles of sharecroppers. Agee traveled to Alabama with photographer Walker Evans, whose achingly beautiful pictures of poor farming families are profoundly moving precisely because of their striking simplicity. In Evans’s haunting, black-and-white images, as in the best documentary photography, there’s no obvious sense of mediation between the subject and the viewer. The gaunt but resilient faces of Evans’s sharecroppers confront us directly, with inch-close immediacy. Evans tends to dissolve into the background of this meeting between those who are seen and those who see them, as sublimely quiet as a stage hand parting a curtain. Evans’s presence in this equation is discernible, but subtle. In some of his most memorable images, Evans’s sharecroppers stand or sit for him as if posing for a formal studio photograph. Their posture, which mimics the rituals of refined family portraits, only serves to underscore their ragged clothing, worn faces, and wearying poverty. What Evans seems to be saying, without quite saying so, is that these sharecroppers are worthy of dignity, too, in spite of their estrangement from economic promise.

But if Evans’s pictures are a study in sublimation, Agee’s accompanying text about the sharecroppers seems as much about Agee as the rural folk he’s supposed to be chronicling. With the title of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which comes from a passage in the apocrypha, an ancient group of texts excluded from the Bible, Agee sounds the keynote of a narrative dense with literary allusion, riddles, and cosmic speculation. To get a flavor of the book, consider Agee’s disclaimer, in which he says that although his nominal subject is Alabama sharecroppers, his real goal “is to recognize the stature of a portion of unimagined existence, and to contrive techniques proper to its recording, communication, analysis, and defense. More essentially, this is an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.”

Not surprisingly, Agee’s Fortune editors balked at his approach, and the story never made it into the magazine’s pages. Agee and Walker eventually expanded the project and got it published as a book, but the volume sold only six hundred copies after its 1941 release and was quickly remaindered. For the most part, readers either embrace Agee’s prose in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, or they simply endure it.

Among the fans is Coles, who celebrates Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in Handing One Another Along, a 2010 book in which he reflects on literature that’s deeply shaped his moral sensibility. When reading Agee’s narrative, says Coles, “I think of Agee as singing in an opera—a sustained, passionate oratorio. I think of the long discourses of the poets of Greece and Rome. . . .”

But even some admirers of Agee’s Alabama odyssey concede that his travelogue is an acquired taste. Novelist David Madden, whose enthusiasm for Agee has slowly grown into “sustained admiration” over the years, admits that, at first, passages in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men struck him as “precious, mannered, pompous, the tone as condescending.”

A much greater critical consensus has gathered around A Death in the Family, the novel Agee was finishing at the time of his own death, and which was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1958. In a story that can often read like a documentary account of Agee’s own childhood, he seems to reconcile his literary expansiveness with the more linear patterns of traditional fiction, creating lovely sentences that quickly invite comparisons to Proust.

“Knoxville: Summer 1915,” a straight autobiographical essay that was written and published years before A Death in the Family and later employed for the novel’s opening, is perhaps the most beautiful evocation ever written of summer as seen through the eyes of a child. Here, Agee describes the evening routine:

Supper was at six and was over by half past. There was still daylight, shining softly and with a tarnish, like the lining of a shell; and the carbon lamps lifted at the corners were on in the light, and the locusts were started, and the fire flies were out, and a few frogs were flopping in the dewy grass, by the time the fathers and the children came out.

The prose of Agee’s boyhood remembrance proved so lyrical that Samuel Barber set a section of “Knoxville: Summer 1915” to music. It was a notable nod to the genius of Agee, who wouldn’t live to see the enduring critical reception he obviously craved.

On May 16, 1955, while putting the last touches on his novel about a family prematurely robbed of its father, Agee died of a heart attack in a New York City taxicab, leaving a wife and children behind. He was a few months shy of his forty-sixth birthday.

If Agee’s life were, indeed, a movie script, then Agee the critic would no doubt have dismissed it as overwritten.