They were young, they were in love, they got married. Simple. But this was Virginia in 1958 and nothing was simple.

The groom, twenty-four-year-old Richard Loving, was your average Joe—a country guy who loved music and drag racing on weekends. He had a knack for fine-tuning engines and won trophy after trophy for his souped-up cars. With his pale eyes, his blond buzz cut, his powerful physique, his face and arms weathered from the elements, he looked like a farmer—or an army sergeant. He worked in construction doing hard physical labor—laying bricks, building houses. A man of few words, Richard knew one thing and was ready to profess it: He loved his wife, Mildred.

And small wonder. A willowy eighteen-year-old with large, liquid brown eyes and a beatific smile that radiated warmth, Mildred moved with uncommon grace. She was so skinny that she had earned the nickname “Stringbean,” which Richard affectionately shortened to “Bean.” They complemented each other: While he was taciturn, and, in public, might appear even a bit brusque, she was gentle and soft-spoken—and expressed herself directly, from the heart. They seemed the perfect couple but for one small detail: her coffee-colored skin. She was, in the fiercely-protected racial borderland of Virginia, a “colored” woman, which made her off-limits as a marriage partner for Richard in the eyes of the law.

The two of them had grown up in an area of rural Caroline County, Virginia, where “people had been mixing all the time” in Mildred’s words. Neither Richard’s nor Mildred’s family saw anything wrong with their dating. It seemed the most natural thing in the world. It had been “love at first sight,” according to one family member, and after several years of courting, the couple decided to make it official. Their home state did not ratify unions such as theirs, but Washington, D.C., did, so they drove ninety miles north, got legally married, and returned home with a wedding certificate, which they proudly hung on the wall in their bedroom.

About a month later, at two o’clock in the morning, Richard and Mildred were roused from sleep by the sound of angry voices and the harsh glare of flashlights in their eyes. As if trapped in the middle of a nightmare, they saw Sheriff Garnett Brooks—the powerful local figure whom everybody in the county knew and feared—looming above them. He was the law, and he was carrying a warrant issued several days earlier by the commonwealth’s attorney; it called for the arrest of the newlyweds. The sheriff had brought two accomplices with him, probably as backup in case there was trouble. Why are you in bed together, the posse demanded? “I’m his wife,” Mildred said. “Not here, you’re not,” the sheriff retorted. When Richard pointed to the marriage certificate on the wall, he was told it didn’t mean squat in Virginia. The couple were hustled out of bed and locked up in the county jail.

Richard was allowed bail the next day, but Mildred was confined for several more days—terrified—in a squalid cell. Though there were other interracial couples living together in the region, either married or unmarried—none of them doing anybody any harm—the local arbiters of justice had decided to make an example of the Lovings. How dare they flout the law? Their crime was compounded because they’d left the state to get married and then returned—a provision in the law specifically outlawed that kind of evasion.

The Lovings had broken the state’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act, a law that went to nearly insane lengths to keep anyone with even one drop of black blood from mixing with a white person. Propped up by pseudoscientific theories that proclaimed the racial superiority of the white race—and using equally suspect methods of classifying who exactly was “white” and “colored” (most Virginia Indians were summarily stripped of their Native American identity and considered “colored”)—the law was based on the notion, held by some, that the white race would be weakened, debased, and made “mongrel” if there were any mixing. For almost four hundred years in Virginia, people had been falling in love across racial lines—and those smitten didn’t give a hoot about abstract notions of “racial purity.” Such was the case with Richard and Mildred. But the state decreed that their marriage, and their love for one another had to be sacrificed on the altar of white supremacy.

Faced with at least a year in prison, the newlyweds took a plea bargain. On January 6, 1959, the local magistrate, Judge Leon Bazile, rendered his verdict: The Lovings’ prison sentence would be suspended for twenty-five years, on the condition that “both accused leave Caroline County and the state of Virginia at once and do not return together or at the same time to said county and state for a period of twenty-five years.” It was a banishment from their home, their families, and their community for a quarter century.

The couple moved to Washington, D.C., where Mildred had a cousin, but they found it hard getting used to city ways. They were country people and they wanted to go home. They missed the open spaces and the slower-paced way of life. They felt adrift. Even if they couldn’t live in Caroline County, Mildred and Richard thought that they could at least visit their families. But they discovered, the hard way, how profound their banishment was: When they went back together to visit Caroline County that first Easter, they were arrested again. From that time on, they had to return surreptitiously, arriving separately, and taking care never to be seen together in public. A neighbor recalled that Richard would scarcely, if ever, leave the house when he was in the county. People might talk. And if the sheriff knew, the couple would be thrown back in jail.

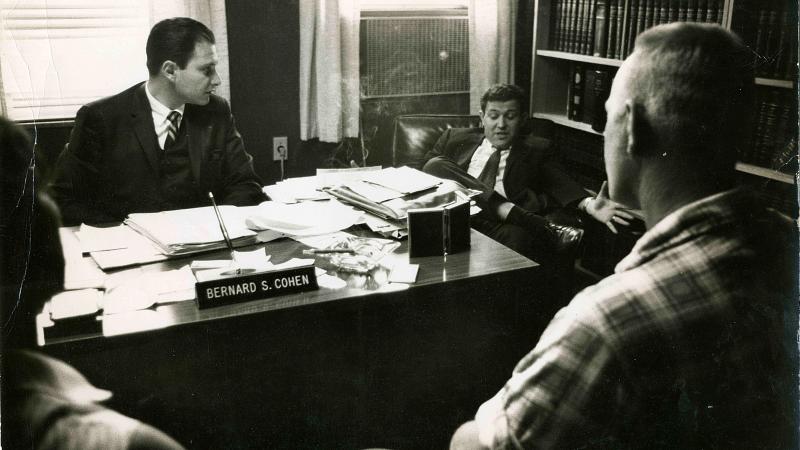

Yet they were determined to remain connected to their home place. Why shouldn’t they? They were Americans. They felt they should be allowed to choose their spouse and live where they wanted. Mildred gave birth to all three of their children in Virginia, but then, each time with a heavy heart, she’d have to return to Washington. She hated bringing up her young ones in the city, and she moaned about it endlessly to her cousin. Then one day in 1963, Mildred’s son was hit by a car. It was, she said, “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” She realized, “I had to get out of there.” Her cousin, sick to death of hearing complaints, suggested that Mildred write to Robert Kennedy, then attorney general of the United States. Mildred composed an eloquent letter to Kennedy, outlining her story. She had been an exile for years. Would he help? Kennedy suggested she contact the American Civil Liberties Union, and the case was soon taken up by a bright young lawyer named Bernard Cohen.

Cohen was barely out of law school, but he was eager to resurrect the case and get it back into the court, which required some deft legal maneuvering on his part, given that the Lovings had been arrested and charged five years earlier. Judge Bazile, who’d sentenced the pair, was in no rush to review his own ruling on their plea. Cohen was soon joined by another newly minted lawyer—Philip J. Hirschkop, who’d cut his teeth on civil rights cases in the Deep South with the activist attorney William Kunstler. Hirschkop would later admit that while he found Mildred “very articulate” and “instantly likeable,” he was immediately suspicious of her husband: “Boy, he looked like a redneck.” But love is a private affair—a mysterious chemistry, at times unfathomable to others.

Hirschkop would discover just how deep his client’s commitment was to his wife. No matter what the end legal result, Richard announced with finality, “I’m not going to divorce her.”

In January 1965, Judge Bazile presided at a hearing on whether to reverse his ruling. He refused to budge. The marriage remained, in the judge’s words, “absolutely void in Virginia.” But he couldn’t resist ending with a rhetorical flourish:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

When that judge used such “horrible language,” Hirschkop declared years later, “he couldn’t have done us a bigger favor.” Cohen agreed: “That racist opinion gave us a clear shot to appeal to the Supreme Court of Virginia.” The highest state court upheld the validity of the law banning interracial marriage, and the Lovings’ convictions remained in place. The U.S. Supreme Court was their final prayer.

It seemed a million-to-one chance that a couple of neophyte lawyers would succeed in bringing this heartrending case to the highest court in the land. But they did. The most basic American rights of freedom and the pursuit of happiness were at stake—the right to live in one’s own home and to choose one’s spouse without undue interference from the state. In the spring of 1967, arguments began over the constitutionality of Virginia’s miscegenation law. The case was identified as Loving v. Virginia.

Richard Loving refused to attend the Supreme Court hearing—he was a private man, averse to publicity. He was not a rabble-rouser, nor was his wife, who opted to stay behind with him awaiting the verdict that would transform their life—one way or the other. But Richard, the man of few words, did have something he wanted his lawyer to convey to the nine justices deciding his fate: “Tell the court I love my wife.” Cohen used that personal plea in the most stirring moment of his argument.

The justices voted unanimously to strike down Virginia’s law, declaring that the “fundamental freedom” of marriage could not be abridged on account of race. The opinion rendered by Chief Justice Earl Warren read in part: “The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” With the court’s ruling, similar laws in fifteen other states eventually would fall.

“I feel free now,” Mildred sighed with relief afterward. Richard announced that he was finally going to build that house for his family that he’d been dreaming of; it would be on land that his father had given him in Caroline County. They could finally go home in peace. And so they did. Eight years later, in June of 1975, a drunk driver crashed into the Lovings’ car, killing Richard. Mildred lost an eye—but even worse, her life’s partner. In a 1994 interview, Mildred would say, “I married the only man I ever loved, and I’m happy for the time we had together.”

A new documentary film, The Loving Story, follows the harrowing tale of this courageous couple. The director, Nancy Buirski, was inspired to take on the project after reading Mildred Loving’s obituary in 2008. “I had a vision for the film immediately,” the filmmaker says. “I wanted to do it in a very narrative way and approach it as a love story.”

While interviewing the lawyers Cohen and Hirschkop, Buirski had a stroke of luck: She learned that a young cinema verité filmmaker from New York, a woman named Hope Ryden, had been moved by the Lovings’ plight in the 1960s and had come south to film events as they unfolded during the court cases. Ryden focused primarily on the family itself—Richard and Mildred and their three children—as they went about their days in hiding at a house outside Caroline County, their lives on hold.

Buirski, along with fellow producer and film editor, Elisabeth Haviland James, and other team members, ferreted out additional archival news footage, even home movies made by a local amateur chronicling life in Caroline County at that time. Eventually, they amassed some one hundred hours of footage. The filmmakers artfully distilled the material and interwove it with evocative photographs that had been taken for Life magazine by Grey Villet, giving the documentary an immediacy and intimacy rare in such films. The viewer can feel the steely determination and quiet dignity of the Loving family. Just regular folks, with no political agenda, trapped by forces larger than themselves. Yet they triumphed.

At a recent screening, Richard and Mildred’s daughter, Peggy—her voice cracked with emotion—said how proud her parents would have been of the film, for it confirmed how utterly committed they had been to one another, and to their marriage. “The only divorce they got was when he was killed by a car accident,” Peggy said. The film will have its first nationwide airing on HBO television—appropriately, on Valentine’s Day.