The 1860 election that made Abraham Lincoln president is sometimes recalled as the ultimate showdown between two politicians—Lincoln and Stephen Douglas—whose dueling arguments in the previous decade helped determine the course of slavery in America and the likelihood of war. What is rarely mentioned is that Douglas not only lost the 1860 election, he didn’t even come in second. In the Electoral College, he came in fourth behind John Bell, the candidate for the Constitutional Union Party.

The man who came in second, the candidate who came closest in electoral votes to defeating Lincoln, was John C. Breckinridge, the standard-bearer of Southern Democrats. But for a split among the Democrats, Abraham Lincoln, who garnered much less than 50 percent of the popular vote, might not have placed first.

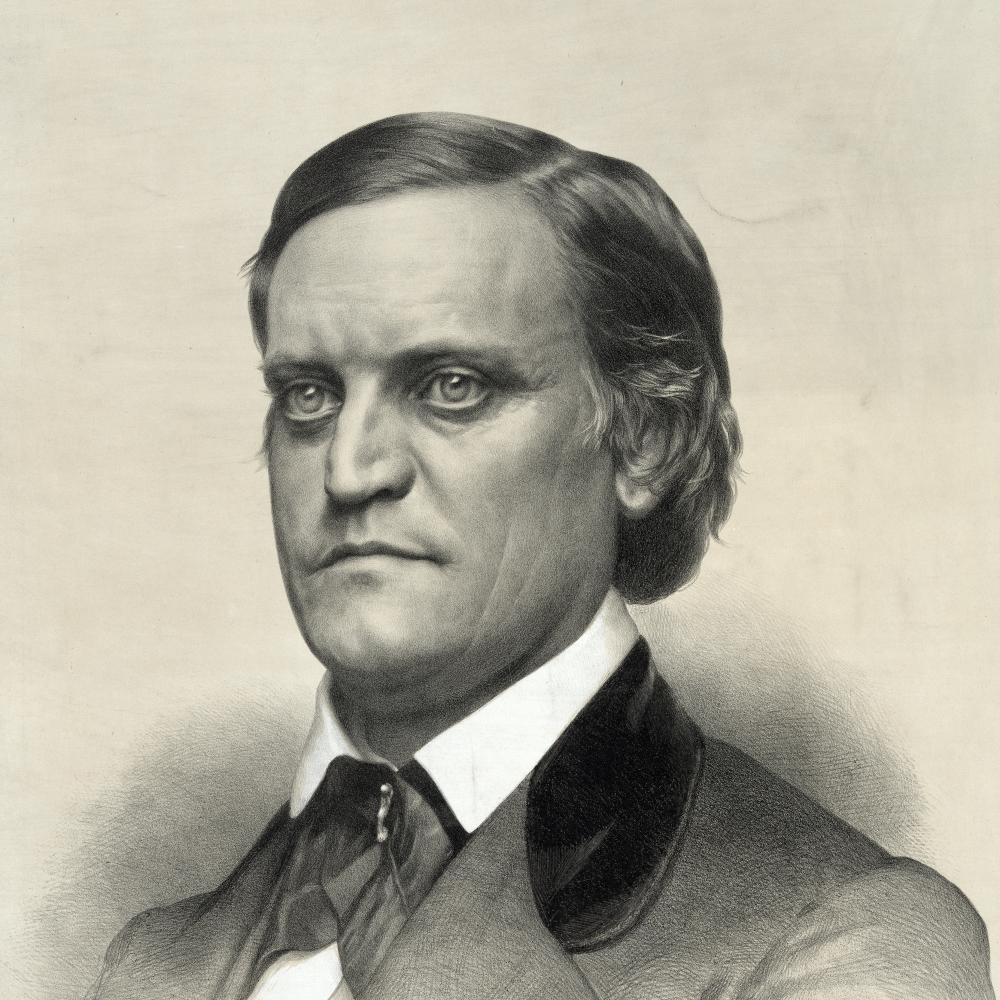

It is surprising that Breckinridge is not better known. He was the youngest vice president ever, elected at the age of thirty-five, and he was the second former vice president, after Aaron Burr, to be accused of treason. A look at his career reveals a man with politics in his blood, but whose personal convictions made it difficult to navigate a moderate course in an era of moral and political extremes. And a look at the 1860 election shows a Democratic Party in severe disarray, such that it could not unite to defeat the Republican upstart from Illinois. Although history is, of course, the study of what did happen, the facts of the 1860 election make it hard to avoid wondering what might have happened instead.

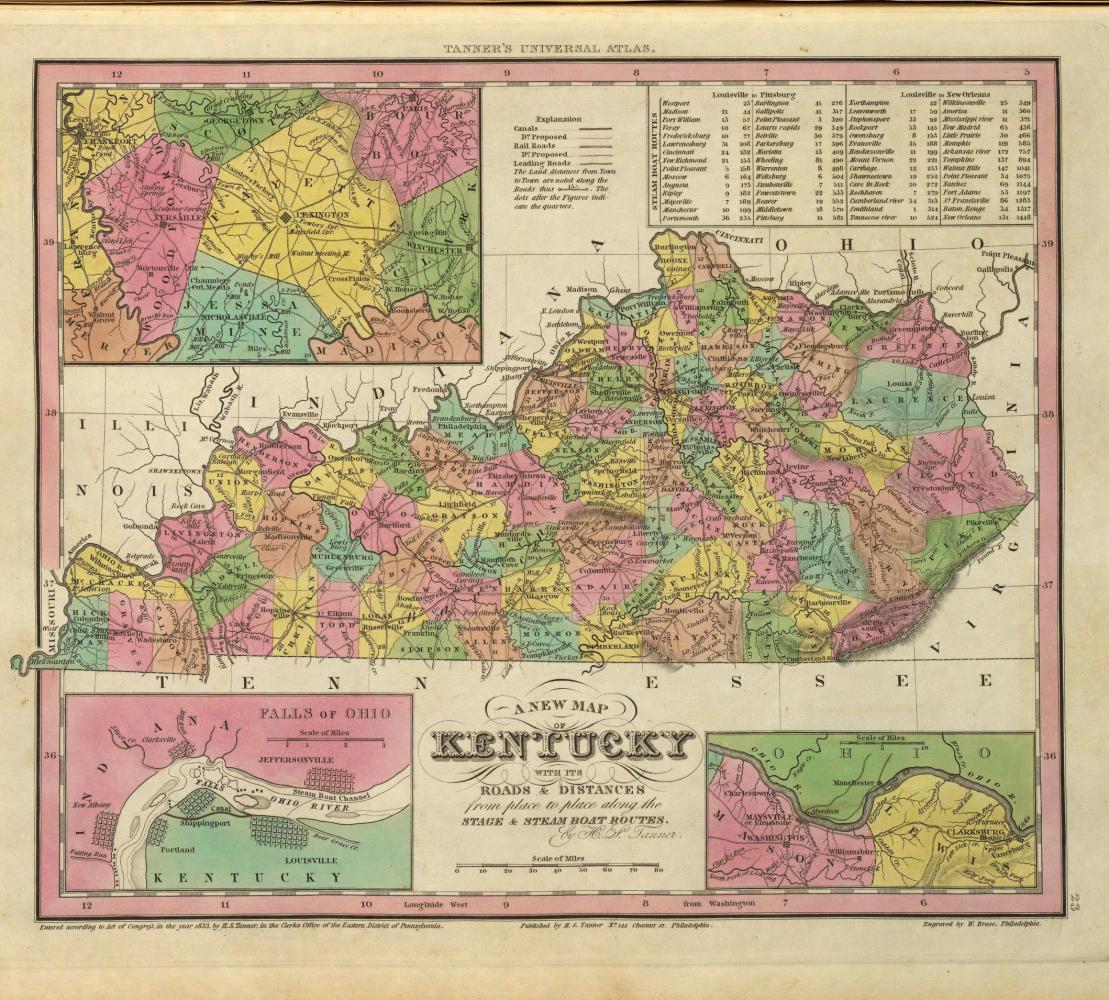

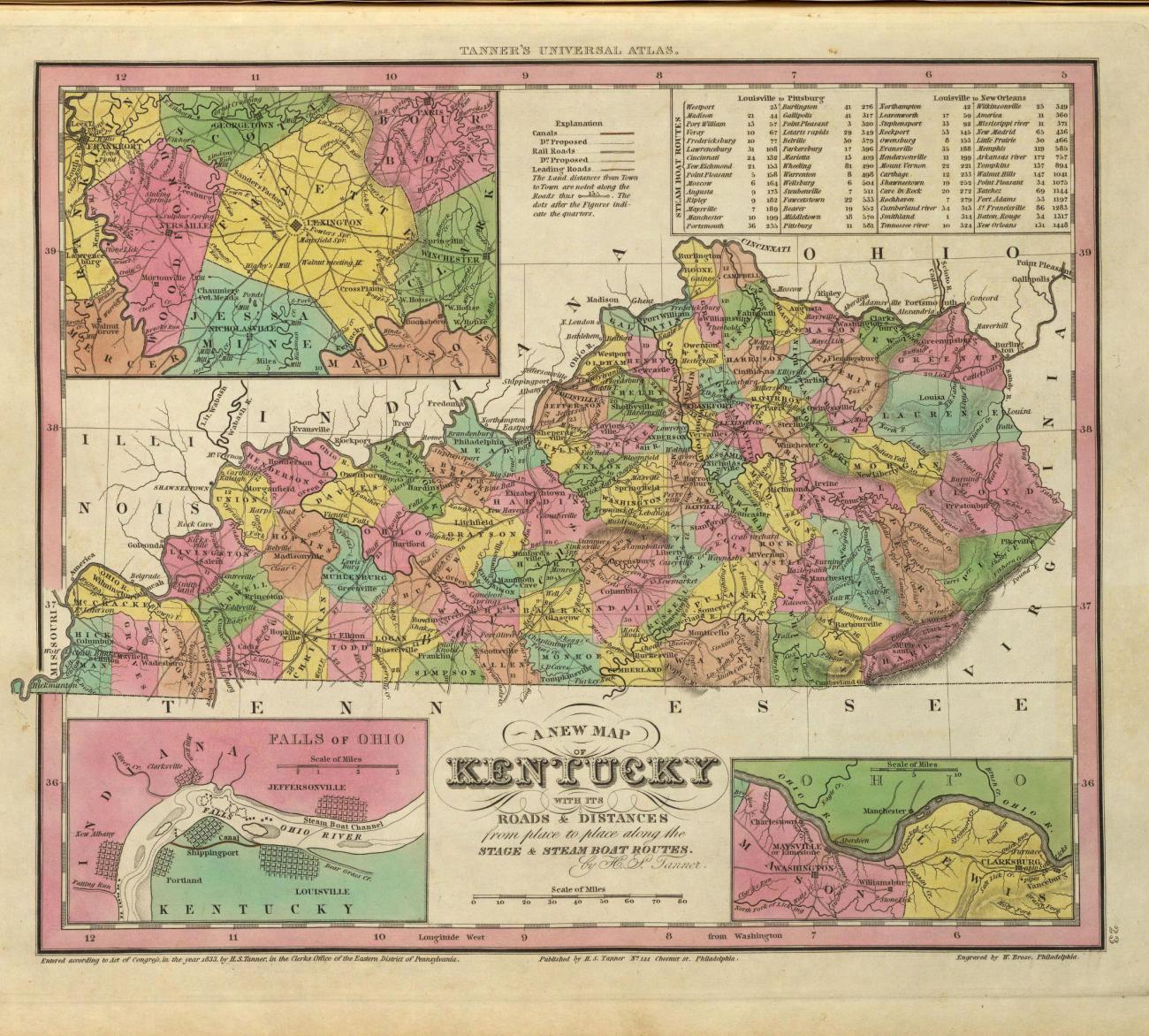

Kentucky Son

That John Cabell Breckinridge became a political force was not surprising. Born on January 16, 1821, in Lexington, Kentucky, he was named after his grandfather, who represented Kentucky in the U.S. Senate and served as Thomas Jefferson’s attorney general. Breckinridge’s father also made a mark on Kentucky politics until a sudden illness felled him in September 1823. Polly Breckinridge, nicknamed “Grandma Black Cap” because of her perpetual mourning attire, took her son’s family into her home. She doted on her grandson, telling him stories of his namesake’s political career, stories that celebrated honor and duty to one’s country. “This teary-eyed old lady and her talk of the law and politics and the principles for which her husband had fought so hard had a profound impact on ‘little Breckinridge,’” writes William C. Davis, author of Breckinridge: Statesman, Soldier, Symbol. It is to Davis that a debt is owed for assembling the details of Breckinridge’s life.

In the fall of 1834, Breckinridge headed to Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, for a more formal education. He developed a taste for the classics, committing to memory the orations of Demosthenes, a Greek statesman known for his political rhetoric, and Pericles, general and “first citizen of Athens.” His studies seem to have made a lasting impression, as Breckinridge would gain renown for his oratory. Upon completing his four years, Breckinridge’s uncle Robert arranged for him to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) for six months.

Breckinridge had decided to read law and began his studies at Princeton, continuing them upon his return to Kentucky under the direction of Judge William Owsley, a prominent Whig jurist and politician. Owsley worked him hard, making him read all four volumes of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England—twice. After six months under Owsley’s tutelage, Breckinridge wrote his uncle: “I am much pleased with the study of law, and having worked the science with something like shape and symmetry, in my mind, I begin to apprehend with some clearness, the leanings of one part of it upon another, and the great principles which govern the system.” A year studying law at Lexington’s Transylvania University followed. In February 1841, he graduated and was found fit to practice law. Breckinridge was all of twenty years old.

Like many young men, Breckinridge wanted to make something of himself and loosen the apron strings that tied him to his prominent family. In the fall of 1841, he borrowed $100 from his uncle and set out for the newly created Iowa Territory. Joining him on his frontier adventure was his cousin Thomas Bullock, with whom he intended to open a law practice. The two men settled in Burlington, the territorial capital and a jumping-off point for settlers venturing farther west. “No doubt I shall suffer many of the trials and hardships incident to a new country,” Breckinridge wrote home, “but if I can preserve my health I have the strongest confidence in attaining my wishes and supporting the honor of our name.” Business, however, developed slowly, and payment frequently came in grain and produce.

In between rendering legal services and cutting a swath as an elegant young bachelor, Breckinridge also flirted with the Democratic Party, which dominated Burlington politics, a development that appalled his Whig relations. The elite families of Kentucky supported the Whigs and their elder statesman, Henry Clay, not those Democrats who hero-worshipped Andrew Jackson. “I felt as I would have done if I had heard that my daughter had been dishonored,” his uncle William wrote Breckinridge upon hearing the news.

Breckinridge’s Iowa sojourn was cut short after a visit home in the summer of 1843 resulted in an engagement to Mary Cyrene Burch, the seventeen-year-old cousin of his partner, Bullock. Rather than bring Mary out to Iowa, Breckinridge closed down his practice in Burlington. He and Mary settled first in Georgetown, Kentucky, before moving to Lexington in 1846. It was by all accounts a loving marriage, producing six children. Years later, their daughter Mary would remark, “I never knew any human love more devoted and loyal than that of my Mother for my Father.”

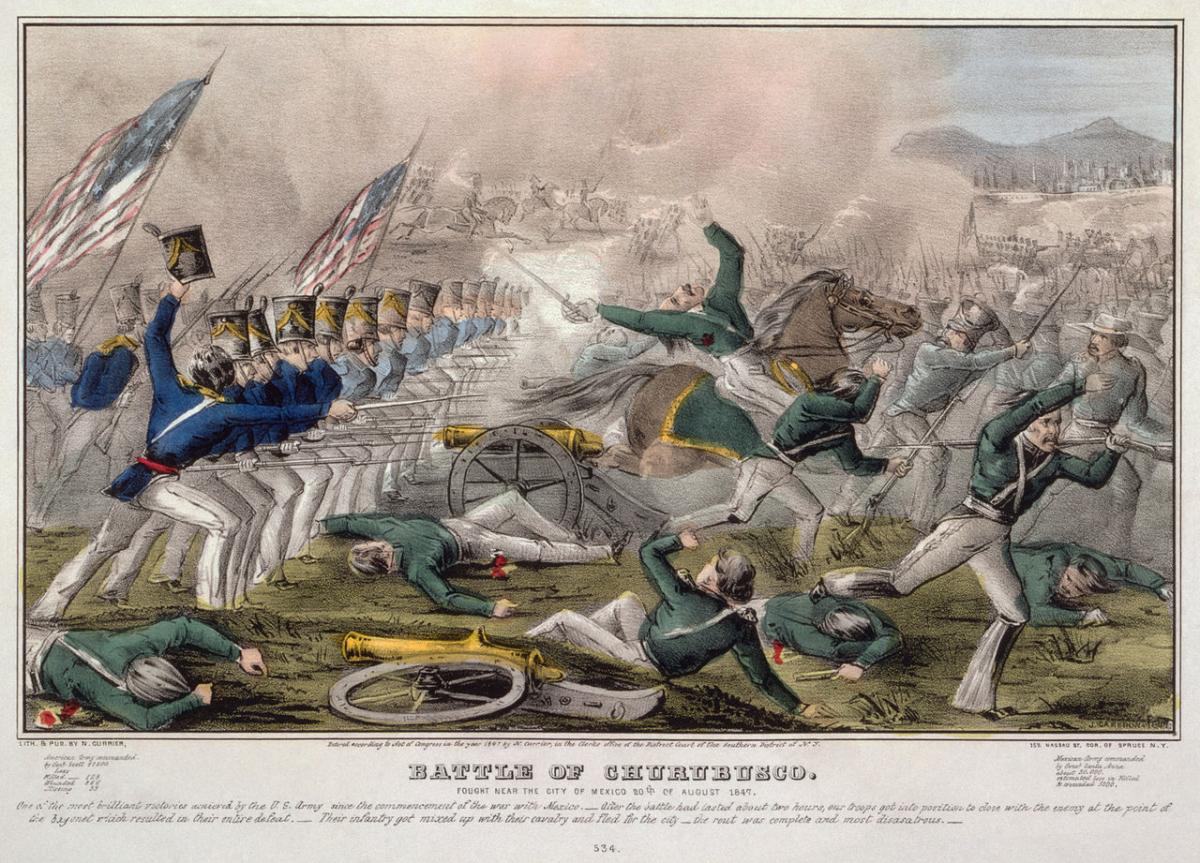

Mexican Adventure

At the end of 1845, the United States annexed Texas, touching off a dispute with Mexico over who owned the land and whether the border should be drawn at the Nueces or the Rio Grande. The Mexican president refused to negotiate (he knew U.S. President James Polk intended to offer him a bum deal), so Polk sent American troops under the command of General Zachary Taylor into the disputed territory. Near the end of April 1846, a Mexican contingent attacked Taylor’s troops, resulting in sixteen American casualties. Shortly thereafter, Polk asked Congress to declare war: “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil.”

For a man like Breckinridge, war offered a chance for both adventure and career advancement. He applied for a commission in the Kentucky Volunteers, only to have his application rejected. Commissions were available for Whigs only. As his friends and colleagues marched off to war, Breckinridge consoled himself by building up his law practice.

In July 1847, Breckinridge was called on to deliver the eulogy honoring officers from Kentucky regiments killed at the Battle of Buena Vista. Speaking at the state cemetery before a crowd estimated between ten and twenty thousand, Breckinridge praised the bravery and lamented the loss of Kentucky’s sons and fathers. Legendary statesman Henry Clay, who mourned a son, wept at Breckinridge’s words. The eulogy is also said to have inspired Theodore O’Hara’s poem “The Bivouac of the Dead,” stanzas of which later adorned Confederate war monuments and headstones, as well as Arlington Cemetery.

In August, Governor William Owsley called up two more regiments. Owsley retained a fondness for his former apprentice, and like many other Whigs he admired Breckinridge’s recent eulogy. Breckinridge thus became the only Democrat to become a commissioned officer. At the beginning of November, Major Breckinridge and the Third Kentucky Volunteers boarded a steamboat for the journey downriver to New Orleans. From there, they steamed to Veracruz, Mexico, making port in late November. By the time Breckinridge and his men marched through the gates of Mexico City in mid-December, the American force had become an army of occupation.

In between his duties, Breckinridge found time to join the Aztec Club, which had been founded by the Army officers who conquered the capital. Within the walls of the club’s headquarters, a palace originally built for the viceroy of New Spain, Breckinridge met men he would later fight with and against on Civil War battlefields: Lieutenants P. G. T. Beauregard, Richard S. Ewell, Ulysses S. Grant, and George B. McClellan; and Captains Robert E. Lee and John C. Pemberton.

Breckinridge’s legal talents also embroiled him in a political conspiracy. When General Winfield Scott seized the port of Veracruz and captured Mexico City, he became a national hero. Scott made no secret of his presidential ambitions. Major General Gideon J. Pillow, a Democrat and Polk’s former law partner, feared that Scott’s popularity would lead to Polk’s defeat in the next election. To poison Scott’s record, Pillow manufactured letters and reports, giving himself credit for Scott’s victories. When Scott brought charges in early 1848, Breckinridge agreed to defend Pillow. The trial became a newspaper sensation, making Breckinridge a national figure as journalists chronicled his monthlong cross-examination of witnesses. The court-martial concluded without reaching a verdict.

Major Breckinridge Goes to Washington

Upon his return from the war, Breckinridge’s political career began to soar. In June 1849, the Democrats drafted him to run for the Kentucky House of Representatives. The campaign proved challenging on a personal level: His uncles William and Robert endorsed the Whig candidate, and his law partner died in the cholera epidemic that engulfed Lexington. Breckinridge, however, prevailed.

In the legislature, Breckinridge made his first official statements on the issue that would define his political career. Slavery, he believed, was a “wholly local and domestic” question, and Congress did not have jurisdiction to regulate or outlaw it. Slaves were also property that needed to be protected. While advocating states’ rights, Breckinridge declared his loyalty to the Union, discounting the notion that disunion could solve the political challenges presented by slavery.

Whereas abolitionists believed slavery to be a moral issue, Breckinridge regarded it as a political matter. The Constitution, he thought, had left it to the states to decide the slavery question. He also had a complicated relationship with slavery personally. As a young man, he advocated the return of slaves to Africa, yet after he returned to Kentucky, he purchased a handful of slaves to help manage the demands of his growing family. At the same time, he represented freed men as part of his legal practice. He was a product of a culture that couldn’t quite transcend the peculiar institution.

While he was in the state legislature, Breckinridge’s political ambitions received a blessing from none other than Henry Clay, who had been at the center of Kentucky and American politics for more than fifty years. At a festival to honor Clay in October 1850, Breckinridge delivered the main toast, praising Clay’s character and career. Moved by the young man’s words, Clay told the crowd that he hoped Breckinridge would use his talents for “the benefit of the country,” as his father and grandfather had. Clay then embraced Breckinridge as a father would a son to a roar of approval from the crowd.

That Clay, an elder Whig statesman, had blessed this rising Democrat didn’t go unnoticed. Sensing an opportunity, Democrats enlisted Breckinridge to run for the U.S. House of Representatives. The seat they picked was the Eighth District, which encompassed Lexington, a traditional Whig stronghold, and Ashland, Henry Clay’s plantation. Breckinridge squared off against General Leslie Combs, a veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. Stumping for six months, he sometimes delivered up to six speeches a day. His hard work paid off. At the age of thirty, Major Breckinridge became Congressman Breckinridge.

He spent two terms in Congress, playing a key role in the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. In the early 1850s, the slavery issue telescoped around the Kansas and Nebraska territories. Southern congressmen wanted the territories organized without any restrictions on slavery. The problem was that the Nebraska territory was subject to the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which prohibited slavery north of the 36°30' parallel in states derived from the Louisiana Territory. Southern Whigs proposed repealing the Missouri Compromise. U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat from Illinois, countered with popular sovereignty: Let the citizens of Kansas and Nebraska vote on whether to own slaves. Douglas’s proposal accorded with Breckinridge’s own views, prompting him to help corral support for the bill. At the end of May 1854, President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

Douglas, Breckinridge, and others who supported the popular sovereignty approach hoped that it would settle the slavery issue. Breckinridge believed that the constant debate over slavery at a national and federal level “distracted the country and threatened the public safety.” Instead, the act touched off what became known as “Bleeding Kansas,” a brutal struggle between pro-slavery and abolitionist forces, the violence of which made many Northerners sympathetic to the goals of the nascent Republican Party.

Mr. Vice President

After serving two terms in Congress, Breckinridge declined another run. While he was in Washington, the Whig machine in Kentucky had redrawn the lines of his district, making defeat in the next election inevitable. Instead, he returned to his law practice and worked the twenty-six acres of land his family called home. He even turned down an offer from President Pierce to serve as ambassador to Spain.

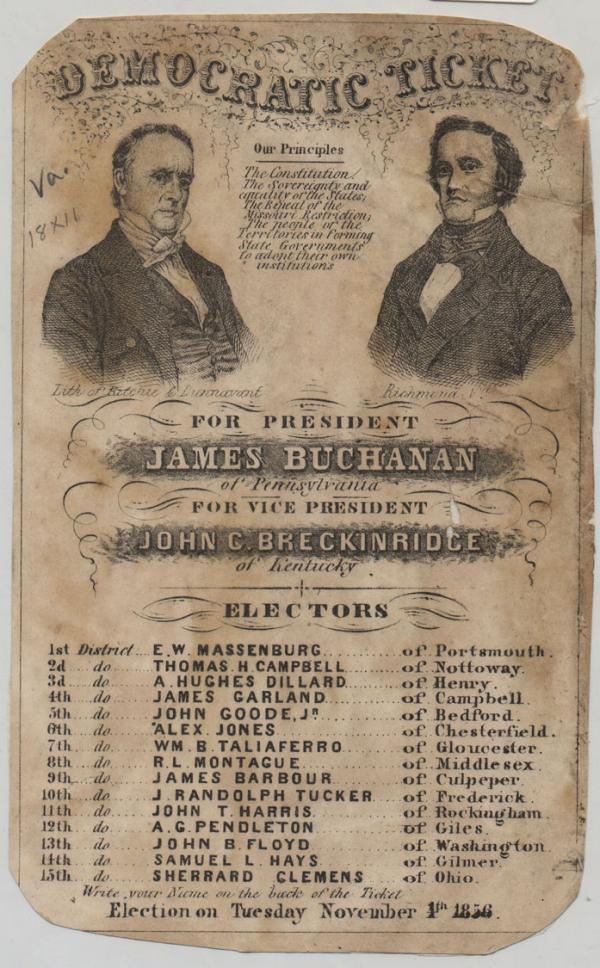

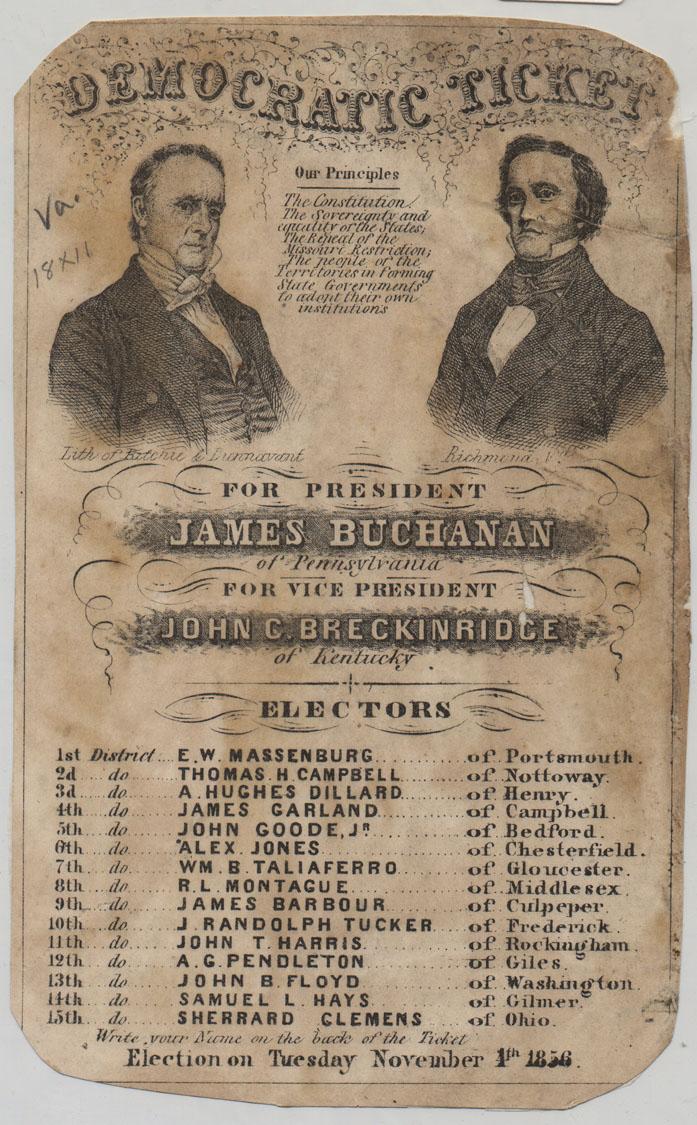

With the 1856 presidential election on the horizon, Democratic politics once again beckoned. Breckinridge journeyed to Cincinnati in June to attend the nominating convention as a delegate from Kentucky. Three men vied for the nomination: incumbent Franklin Pierce, Stephen Douglas, and James Buchanan. Four years earlier, Pierce had campaigned on a platform of uniting the country, but the Kansas-Nebraska Act had only made the slavery issue more divisive and Pierce unelectable. The same went for Douglas. That left Buchanan, a sixty-five-year-old bachelor with a resume that included representing Pennsylvania in both the House and Senate and serving as Polk’s secretary of state. In Buchanan’s favor was that he had nothing to do with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, having been in England acting as U.S. ambassador to the Court of St. James’s from 1853 to 1856. After seventeen ballots, the nomination belonged to Buchanan.

That left the vice presidential slot. Congressman William Richardson of Illinois decided that his good friend Breckinridge would make a fine vice president and quietly lobbied his fellow delegates. A Breckinridge candidacy made sense: He had a national reputation, Douglas and the Northern Democrats would regard him as an ally, and Southern Democrats could claim him as their own. There was, however, a problem with Richardson’s plan: Linn Boyd, also from Kentucky, had been campaigning for the job. That meant the Kentucky delegation couldn’t put Breckinridge’s name forward.

When the call came for nominations for vice president, Breckinridge was stunned to hear the Louisiana delegation offer his name. His supporters had chosen to keep their plan secret, giving him no advance warning. Standing on a chair so he could be seen and heard, he offered gratitude followed by regret. He would not oppose Boyd. One delegate, J. Stoddard Johnson, wrote of the scene: “That speech was irresistible . . . though sincerely declining made him more votes on the first ballot than . . . Boyd secured after a year or two’s active electioneering and wire pulling.” After the end of the first round of balloting, Breckinridge polled second, behind John Quitman of Mississippi and ahead of Boyd. The next round delivered the nomination to Breckinridge, sending the convention into a deafening round of cheers and applause.

The convention delegates also approved a party platform that endorsed states’ rights, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the annexation of Cuba, which allowed slavery.

Buchanan and Breckinridge were in for a tough fight. Bleeding Kansas and the slavery issue had led to the collapse of the Whig Party and the birth of the Republican Party. In July 1854, Free Soilers, anti-slavery Democrats, and disaffected Whigs held a meeting in Jackson, Michigan, to organize a new party devoted to repealing slavery, which they regarded as “the great moral, social, and political evil.” Over the next two years, the Republican Party made inroads in the North and West, making it the country’s first major sectional party. It is important to note that not everyone who joined the Republican Party was an abolitionist or opposed slavery on moral grounds. Some merely wished to maintain the status quo or stop its spread for economic reasons. Many Northern businessmen believed that slavery gave the South an unfair economic advantage.

The Republicans held their first nominating convention in June 1856 in Philadelphia. The delegates picked John C. Frémont, an explorer whose maps and reports helped guide thousands of settlers over the Rocky Mountains to California, as their presidential candidate and William Dayton, a former Whig senator from New Jersey, for vice president. The Republican platform called for Kansas to be admitted to the Union as a free state, no further extension of slavery, and the construction of a transcontinental railroad.

To make things interesting, former president Millard Fillmore ran as the candidate for the Know-Nothing Party. Born of a secret society founded in the early 1840s in New York, the Know-Nothings were anti-immigration and anti-Catholic. They believed that only native-born Americans should hold elected office, and citizenship should be conferred only after an individual had lived in the United States for twenty-one years. Their party platform advocated popularity sovereignty in the territories and preservation of the Union.

The fall of 1856 saw a flurry of picnics, mass meetings, torchlight parades, and scathing editorials—along with beatings, riots, and dirty tricks—as the parties campaigned. Placards and posters celebrated Buchanan and Breckinridge as defenders of the Union. There were even songs:

Oh! Buck and Breck are bound to win—

No power can stop their coming;

The Pennsylvania steed is lucky;

And so [is] the one from Old Kentucky

Pennsylvania is safe and lucky

So’s the hoss from Old Kentucky.

Buchanan heeded the convention of the era, which dictated candidates abstain from campaigning. Breckinridge, however, put his oratorical skills to work, giving speeches around the country.

The Democrats triumphed in November, earning 45.3 percent of the popular vote (174 electoral votes), with the Republicans earning 33.1 percent (114 electoral votes). The victory made John C. Breckinridge the youngest vice president in the history of the country, a distinction he still holds.

Once installed in the White House, Buchanan had no use for his wunderkind vice president, rarely meeting or consulting with him. Buchanan regarded Breckinridge with suspicion, because Breckinridge initially backed Douglas for president.

Breckinridge’s primary duty while serving as vice president was presiding over the Senate. In early 1859, he cast a tie-breaking vote to defeat the Homestead Act, but the chamber regrouped and passed the measure, only to have Buchanan veto it. Breckinridge also presided over the final session of the Senate in the Old Chamber, delivering a much-printed speech that celebrated the institution, while also reminding his colleagues that they had an obligation “to preserve, to extend, and adorn” the inheritance passed down to them by the Founding Fathers. In a country where talk of secession by the Southern states had gone from hushed whispers to outright calls, Breckinridge made a plea for unity.

Presidential Candidate

In December 1859, the Kentucky General Assembly appointed Breckinridge to the U.S. Senate, with his term to start in March 1861. His return to Washington was assured, but there was no reason he couldn’t return to the White House. Rumors began to swirl of a possible presidential candidacy. Breckinridge, however, played his hand close to his vest, letting people speculate as to his intentions. He told his uncle, “I have neither said or done anything to encourage [such talk]—and am firmly resolved not to do so.”

That Breckinridge was being talked of as a candidate indicates how much Democratic fortunes had shifted. In the previous two elections, the party had been able to unify behind a Northern Democrat with a moderate approach to the slavery issue. The advent of the Republican Party made that approach more difficult. The Democrats faced a conundrum: how to appeal to Northern voters sympathetic to abolition, while maintaining the support of proslavery Southerners. For some Southern Democrats, Breckinridge represented a possible solution—a candidate who could unify the party and have mass appeal.

The Democratic convention was set for Charleston, South Carolina, in late April 1860. For Northern Democrats, traveling to South Carolina, a hotbed of secession fever, was akin to traveling into hostile territory. Since John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, the South had been boiling with indignation at Northern interference in its affairs. Brown, a firebrand abolitionist, assaulted the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in order to procure weapons that could be used to start slave uprisings. Local militia and a contingent of U.S. Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee foiled the assault. Brown was found guilty of treason and sent to the gallows at the end of December.

“John Brown’s ghost stalked the South as the election year of 1860 opened,” writes James McPherson in Battle Cry of Freedom. The Harpers Ferry raid and Brown’s plans to incite mass slave uprisings represented the daylight manifestation of Southern whites’ worst nightmare. While the slave-holding South contended that slaves were treated well and happy, they also lived in fear of a mass slave rebellion. Their fears weren’t without foundation: In 1860, there were four million slaves in the South. “Keyed up to the highest pitch of tension, many slave holders and yeoman alike were ready for war to defend hearth and home against those Black Republican brigands,” writes McPherson.

The Southern Democrats came to the convention ready to fight for the preservation of slavery—and a candidate other than the Northerner, Douglas. Breckinridge, who did not attend the convention, asked his friends not to nominate him. Another Kentucky son, James Guthrie, president of Louisville and Nashville Railroad, was keen on the nomination, and Breckinridge had pledged to support him. Breckinridge’s friends reluctantly agreed, even withdrawing his name when it was placed into consideration.

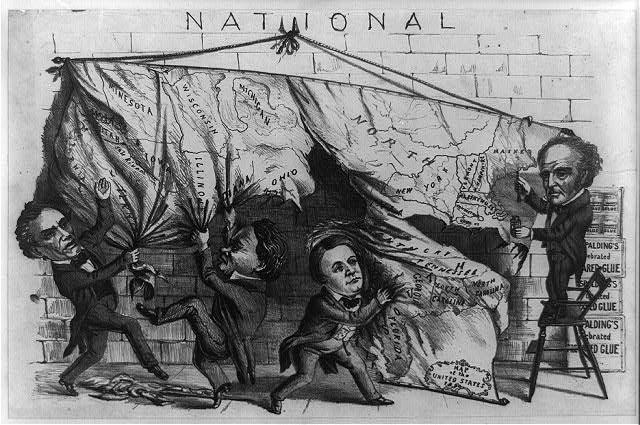

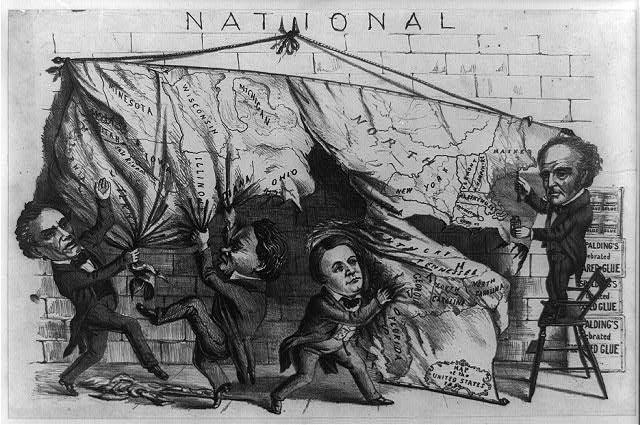

But before the nominations for president and vice president could begin, the convention had to settle on the party platform. When Southern Democrats demanded a plank calling for federal protection of slavery and its extension into new territories, the Northern Democrats refused. They wanted popular sovereignty as the party plank. The Northern Democrats prevailed after two days of intense bargaining, but then the Southern delegates walked out. Unable to agree on a platform or a candidate—Douglas couldn’t muster the required two-thirds votes—the convention dissolved.

In June, the Democrats reconvened in Baltimore, their ranks consisting mostly of Northern states. They nominated Douglas for president and adopted a popular sovereignty platform. Shortly after, the Southern Democrats met in the same city and selected Breckinridge as their presidential candidate. Breckinridge, who was in Washington, D.C., learned of his nomination by letter. In the time between the two conventions, Breckinridge’s attitude toward a candidacy had changed, owing in part to the acrimonious proceedings in Charleston and the Democratic Party’s refusal to accommodate the wishes of its Southern wing. In accepting the nomination, Breckinridge wrote that “I feel that it does not become me to select the position I shall occupy, nor shrink from the responsibilities of the post to which I have been assigned. Accordingly I accept the nomination from a sense of public duty, and, as I think, uninfluenced in any degree by the allurements of ambition.”

It was a disingenuous acceptance from a politically ambitious man, but Breckinridge also accepted out of a desire to preserve the Union. “It is well to remember that the chief disorders which have afflicted our country have grown out of the violation of State equality, and that as long as this great principle has been respected we have been blessed with harmony and peace,” he wrote. The party he represented, however, advocated states’ rights, slaves as personal property, entry of territories into the Union whose citizens vote for slavery, and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. Breckinridge may have seen himself as defending a constitutional principle, but the new party—the Southern Democrats—defended slavery. And many in the party were prepared to secede if the Republicans were elected.

By accepting the nomination, Breckinridge knowingly allowed the Democratic Party to split. It was one thing for the Southern wing to hold a convention, quite another for it to field its own candidate. The Democrats and Republicans both understood that the split would almost guarantee a Republican victory. Indeed, Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi tried to broker a withdrawal of both Breckinridge and Douglas in favor of a candidate acceptable to both factions of the party, but his efforts came to naught. In the end, Douglas proved to be the main obstacle. He felt betrayed by the Southern Democrats and believed that he alone was acceptable to Northern Democrats.

Breckinridge found himself in a four-way race for the presidency. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois beat out Senator William Seward of New York to secure the Republican nomination. The remnants of the Whig Party coalesced into the Constitutional Union party, devoted to the preservation of the Union. They nominated John Bell of Tennessee, a former Speaker of the House of Representatives as their candidate.

With the Republicans not even on the ballot in ten Southern states, the election of 1860 devolved into a sectional contest: Lincoln versus Douglas in the North and Breckinridge versus Bell in the South. All of the candidates, except for Douglas, who actively campaigned, stayed home and let their lieutenants and parties campaign for them.

Breckinridge’s silence enabled critics on both sides to make hay of his record. Because he had never made militant proslavery remarks, it was easy to paint him as sympathetic to emancipation. His oft heard plea to preserve the Union didn’t sit well with those clamoring for secession. In September, he decided to confront his critics in the one and only speech he gave as a presidential candidate. Before a crowd gathered at Henry Clay’s Ashland estate, Breckinridge challenged anyone in the audience to name a time when he had voiced sympathy with emancipation. No one offered a challenge. He then turned to the question of secession, arguing that he and his party were running to preserve the Union. Breckinridge, however, refused to engage the question of whether the Southern states would be justified in seceding if Lincoln was elected. “The address won great applause, and wide praise,” writes Davis, “but it was, nevertheless, a disappointment. Breckinridge said nothing that he had not said before, and he left too many questions unanswered.”

When the votes were tallied, Lincoln had earned 180 electoral votes, Breckinridge 72, Bell 39, and Douglas 12. Douglas, however, placed second in the popular vote, earning 29.5 percent to Lincoln’s 39.8 percent. Breckinridge earned only 18.1 percent, with Bell claiming 12.6 percent. Breckinridge won eleven states—Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas—but failed to win Kentucky. He lost his home state to Bell by almost 13,000 votes. “By and large, what Breckinridge did represent in this election was the spirit of moderation and conciliation,” writes Davis. “Those who stood the most to lose by emancipation or abolition, and the most to gain by disunion, had gone for Bell.”

What would have happened if the Democratic Party hadn’t split? Could the Democrats have won? The answer lies in the math. With 303 votes up for grabs in the Electoral College, a candidate needed 152 votes to win. Lincoln won 180 electoral votes. There were only three states where combining the votes earned by Breckinridge, Douglas, and Bell would have handed those electoral votes to a unified Democratic ticket: California, New Jersey, and Oregon. Together, they account for only 11 electoral votes, which still leaves Lincoln on top with 169. There were two other states, where Lincoln’s margin of victory was slim: Indiana (51.1 percent) and Illinois (50.7 percent). Lincoln would have needed to lose both states—and their combined 24 electoral votes—in order to give the Democrats a victory. Could Breckinridge alone have delivered those votes? It’s not likely as voters in those states overwhelmingly preferred Douglas to him. A Breckinridge-Douglas ticket? That just might have been a game changer.

Lincoln’s election triggered what became known as “Secession Winter,” as seven states seceded and formed the Confederate States of America on February 4, 1861.

Breckinridge returned to Washington in early 1861 to conclude his duties as vice president and take up his Senate seat. His home state of Kentucky still remained in the Union. On February 13, Breckinridge, acting as president of the Senate, announced the results of the election: “Abraham Lincoln, of Illinois, having received a majority of the whole number of electoral votes, is elected President.” In March, he swore in the new vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, and took his seat in a greatly reduced Senate. Even though his heart lay with the South, he had come to Congress, he told his colleagues “with a lingering hope that something might yet be done to avert a war.”

It was a short road from secession to war. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston’s harbor, kicking off the Civil War that would grip the country for the next four years. Despite his misgivings, Breckinridge stayed in Washington, frequently casting the single vote against Lincoln’s policies. He opposed the blockade of the Southern coast and what he regarded as the president’s usurpation of the Constitution. He also dreaded what lay ahead for the nation: “grim war, with death and devastation in train, with ruin for every interest, and sable for many a hearthstone.”

At the end of the Senate term, Breckinridge returned to Lexington, only to watch as both Union and Confederate troops invaded Kentucky during the fall. When Kentucky renounced its neutrality and sided with the Union, Breckinridge became a wanted man, fleeing to Confederate territory. There he joined the Confederate cause, assuming the rank of brigadier general. In a manifesto published in October 1861, Breckinridge explained that Lincoln’s despotism had forced him to abandon the Union: “I exchange with proud satisfaction a term of six years in the United States Senate for the musket of a soldier.”

Breckinridge’s oratorical powers and embrace of the newly formed Democratic Party helped him climb quickly in Kentucky and national politics. But his moderate stance in an era of extremes could only take him so far. Breckinridge’s moderation also perhaps accounts for his not being better known. A man who tries to chart a middle way through a provocative period in history doesn’t lend himself to a dramatic story in the same way as a firebrand abolitionist or an upstart lawyer. When it comes to an issue like slavery, we are also perhaps uncomfortable with those who tried to find accommodation on an issue that appears morally non-negotiable more than 150 years later.

Despite dreading the war, Breckinridge distinguished himself on the battlefield, leading Confederate troops at Shiloh, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Cold Harbor. In 1864, Breckinridge, working with Jubal Early, mounted a bold raid on Washington, D.C., laying eyes on the U.S. Capitol before being forced to retreat. In 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, tapped Breckinridge, now a major general, to be his secretary of war. Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox in April 1865 turned Breckinridge into a fugitive. Accused of treason for his role in the Confederacy, Breckinridge joined Aaron Burr in the rogues’ gallery of disgraced vice presidents. He fled to Cuba, then England, and Canada. The general pardon of Confederates issued by President Andrew Johnson on Christmas Day in 1868 allowed him to return to his home state of Kentucky. He never entered politics again.