In early 1861, twenty-three-year-old Henry Adams sailed from East Boston aboard the steamer Niagara, traveling in the company of his father, mother, and sisters. After the family made port in Liverpool, they journeyed to London. Henry’s father, Charles Francis Adams, had been appointed American minisiter to Britain, a position held by his father, John Quincy, and his grandfather, John. Henry had been called away from his law studies in order to serve as his father’s unofficial private secretary, a duty that would prove both trying and exciting. Years later, when writing The Education of Henry Adams, a memoir of his adventures and life lessons, Henry titled the chapter of his first year in London “Diplomacy.”It was an apt title, but only vaguely suggested the drama that had engulfed his father and the Union. The Adamses arrived in London just as relations between the Union and Britain came to a boil over Britain’s recognition of the Confederate States of America and its neutrality in the Civil War.

During the next seven months, Henry received an education in just how close two countries could come to war.

The Problem with Being Neutral

Following the creation of the Confederate States of America in February 1861, President Jefferson Davis set his sights on gaining recognition by the European powers. He believed that Britain and France’s dependency on cotton—and the need to keep their factories humming with the production of cloth—would make them naturally sympathetic to the South. The very idea of a European power recognizing the Confederacy struck terror in the hearts of Lincoln’s cabinet. Recognition would signal the legitimacy of the rebel state and possibly lead to outside support for its war effort.

In the spring of 1861, the Confederacy sent a three-man delegation to Europe to make its case for recognition. The delegation met informally with British foreign secretary Lord John Russell on May 3. During the meeting, the envoys stressed the peaceful intent of the new Confederate state and the importance of the cotton trade to Britain. Emphasizing cotton was a savvy strategy given that Britain imported three-fourths of its cotton from the American South. The delegation’s message of peace, however, rang hollow. News of the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter in mid-April had just reached London. The North and South were officially at war.

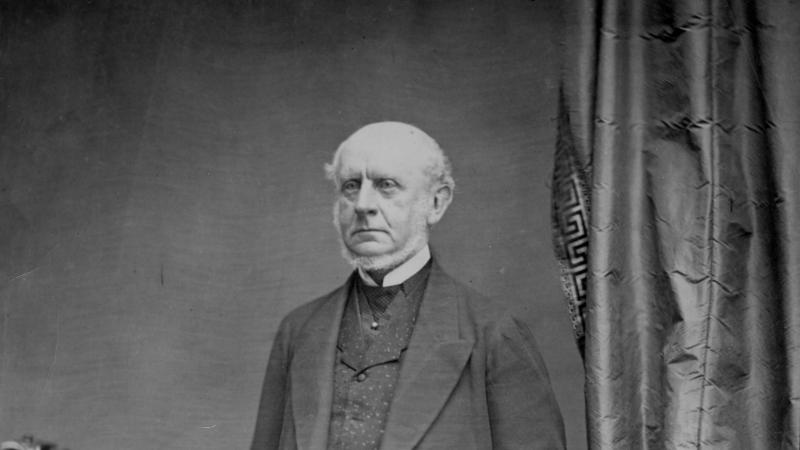

Rather than sit idle, the Lincoln administration launched its own diplomatic offensive, appointing Adams as the new minister to Britain. Aside from being descended from American political royalty, Adams had campaigned against slavery and acquitted himself well in the Massachusetts legislature and as a U.S. congressman from 1859 to 1861. He’d also built a reputation for himself as a historian and biographer of his grandfather’s life and career. Adams had one other key qualification: He was good friends with Secretary of State William Henry Seward.

Adams had the misfortune of arriving in London on May 14, the day after Britain declared that it would remain neutral in the war. Since he hadn’t even presented his credentials to the queen, let alone set foot in the American embassy, Adams’s mission could not be seen as a failure. Still, it wasn’t the best way to start off his new post. When he was presented to Queen Victoria on May 16, Adams expressed “in few words the desire of our government to continue our amiable relations.”

From Washington, it appeared that Britain was slowly laying the groundwork for recognizing the Confederacy. By declaring itself neutral, Britain had conferred on the Confederacy the status of a belligerent power, no small thing. Under international law, the Confederacy could now use loans to purchase war matériel from neutral countries. But for Russell and Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, British neutrality wasn’t about helping the South, but about keeping Britain from becoming embroiled in the Civil War and protecting British trade.

Adams would serve as a check on Seward’s bellicose impulses. Upon hearing of the meeting between Russell and the Confederate envoys, the secretary of state exploded: “God damn them, I’ll give them hell.” When he learned of Britain’s declaration of neutrality, Seward poured his anger into a dispatch that ordered Adams to break off relations if Britain had any more dealings with the Confederacy. Should that day come, wrote Seward, “we from that hour, shall cease to be friends and become once more, as we have twice before been forced to be, enemies of Great Britain.”

Seward’s message, which has become known as his “bold remonstrance,” was tempered by Lincoln, who didn’t share Seward’s quarrelsome approach. Lincoln circled the inflammatory passage in the draft, asking that it be removed. In case the passage made it in, Adams was instructed to use the dispatch only for guidance. He was not to share it with anyone in the British government.

Even toned down, Adams and his son Henry found the language alarming. “A despatch arrived yesterday from Seward,” Henry wrote his brother, “so arrogant in tone and so extraordinary and unparalleled in its demands that it leaves no doubt in my mind that our Government wishes to force a war with all of Europe.”

Rather than rattle his sabre in Whitehall, Adams set about courting British officials, attending a string of dinners and functions. Growing up in American legations in London and St. Petersburg had taught Adams the importance of restraint and charm. “Adams concealed Seward’s iron fist in a velvet glove,” writes James McPherson in Battle Cry of Freedom. For his efforts, Adams was rewarded with a confession from Russell that Britain had no intention for the foreseeable future of recognizing the Confederacy.

As his father settled into his diplomatic duties, Henry found it hard to find his place. Four decades later he described the isolation he suffered at this moment, writing about himself in the third person in The Education of Henry Adams: “To him, the Legation was social ostracism, terrible beyond anything he had known. Entire solitude in the great society of London was doubly desperate because his duties as private secretary required him to know everybody and go with his father and mother everywhere they needed an escort. He had no friend, or even enemy, to tell him to be patient.”

Two Men Depart from Havana

In the wake of the South’s victory at Bull Run on July 21, 1861, Jefferson Davis again decided to press Britain and France to recognize the Confederacy and selected new envoys for the task. For London, Davis chose James M. Mason, a Virginia lawyer who had led the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for a decade. Mason authored the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and backed the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, both of which helped fan the flames of abolitionism. Adams regarded Mason as “provincial and intensely arrogant.” Around the Capitol, Mason was known as much for his support of slavery as for his habit of chewing tobacco and regularly missing the spittoon.

To court Napoleon III, Davis enlisted John Slidell. After a duel forced him to flee New York, Slidell claimed Louisiana as home, climbing his way to political prominence in his adopted state. He served as President James Polk’s envoy to Mexico during the U.S.-Mexican War and managed Buchanan’s presidential campaign. While serving as a U.S. senator from 1853 to 1861, Slidell became one of the foremost advocates of states’ rights. Adams feared Slidell’s appointment, calling him “the most dangerous person to the Union the Confederacy could select for diplomatic work in Europe.”

In sending them on their way, Davis charged the duo with making London and Paris understand that “the Confederate States have thus been forced to take up arms in defence of their right to self-government and in the name of that sacred right they have appealed to the nations of the earth not for material aid or alliances offensive and defensive but for the moral weight which they would derive from holding a recognized place as a free and independent people.” The Confederate states wanted legitimacy and the right to trade—nothing more.

The Union blockade of Southern ports prevented Mason and Slidell from booking direct passage to Europe. Instead, they would have to take a ship to the Caribbean, and from there catch a British mail packet sailing for Southampton. Mason and Slidell’s mission was an open secret, which meant the Union Navy was on the lookout for any ship that might be carrying their party. Nevertheless, on October 12, under the cover of darkness and aided by a rainstorm, Mason and Slidell slipped out of Charleston Harbor, past the Union blockade, and made for Havana.

Mason and Slidell’s arrival and stay in Cuba were reported in the local papers, catching the eye of Charles Wilkes, the captain of the twelve-gun USS San Jacinto. In the twilight of an undistinguished career, the sixty-two-year-old Wilkes longed to leave his mark on history. He fastened on to the idea of preventing Mason and Slidell from making it to Europe. But he had a problem: The Confederate envoys would be sailing on a neutral British ship, which meant Wilkes needed a legal pretext for stopping the ship and arresting them.

Wilkes poured over international law books looking for a pretext. The U.S. Consul General in Havana also studied the question at Wilkes’s request, but couldn’t find one. Back on the San Jacinto, Wilkes continued his search, finally settling on a somewhat fanciful rationale: Mason and Slidell were the “embodiment of dispatches,” which made them contraband and subject to seizure.

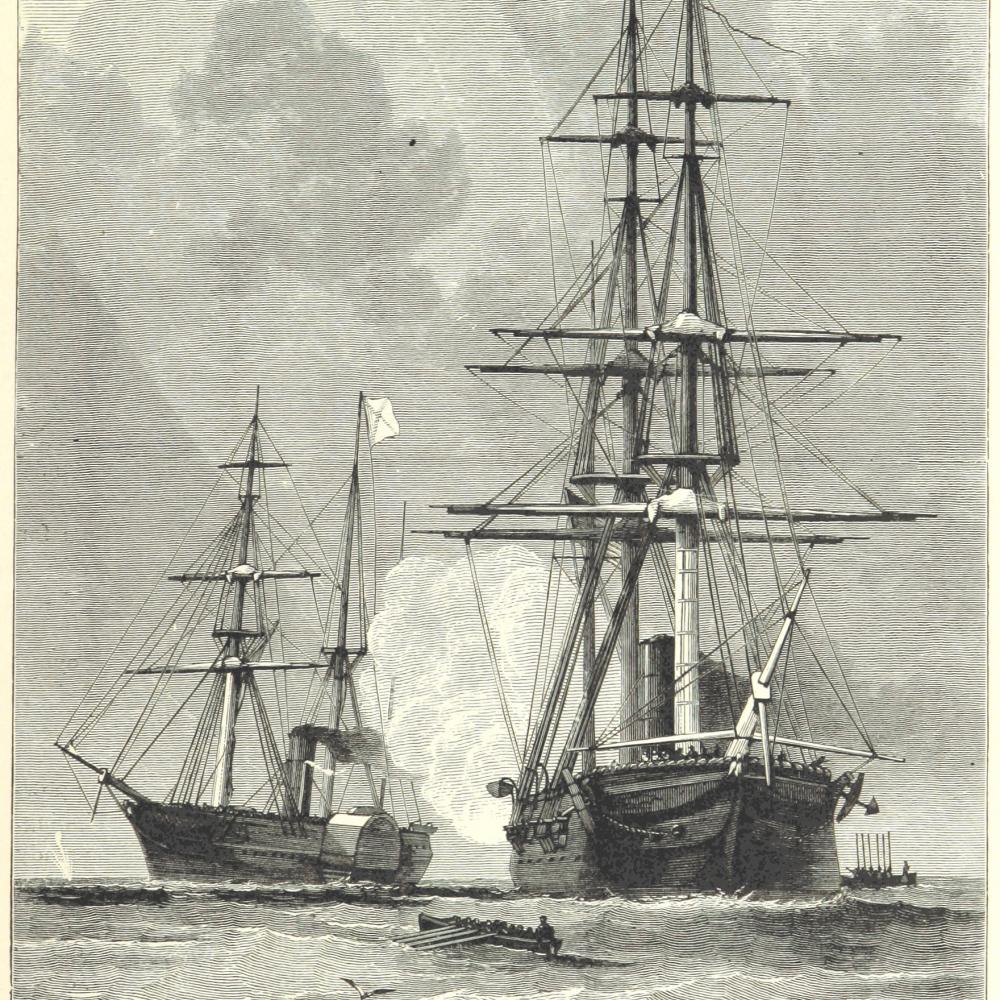

On the morning of November 7, the RMS Trent, a British mail packet, left Havana, carrying Mason and Slidell. Shortly after noon on November 8, the Trent caught sight of a steamer with the appearance of a man-of-war. The steamer didn’t show her colors, so the Trent went about her business. At a quarter past one, the San Jacinto fired a shot across the bow of the Trent and ran up her colors, revealing herself as an American ship. Another shot followed, this one landing only about one hundred yards ahead of the Trent. The captain of the San Jacinto intended to board the Trent.

With the Trent stopped, a landing party set out from the San Jacinto under the command of Lt. Donald Fairfax. The Trent’s captain, James Moir, didn’t appreciate being stopped by the Union nor did he think much of Fairfax’s demand to search his ship. According to one eyewitness, Moir let Fairfax have a piece of his mind: “For a damned impertinent, outrageous puppy, give me, or don’t give me a Yankee. You go back to your ship, young man, and tell her skipper that you couldn’t accomplish your mission, because we wouldn’t let ye. I deny your right of search. D’ye understand that?” Moir’s bravado was his best weapon. The San Jacinto sat only two hundred yards away, with her ship’s company at quarters, ports open, and guns at the ready.

Moir’s bluster, along with the angry response of the crew and passengers, seemed to unsettle Fairfax, who was under orders to search the ship, seize any correspondence, and arrest the Confederate envoys. Instead, Fairfax seized only Mason, Slidell, and their secretaries, taking four prisoners total. Slidell made a misguided attempt to escape out of a porthole, an act of desperation that only could have led to a watery grave but fortunately didn’t. Lt. Fairfax left behind the Confederate dispatch bag, which had been locked in the mailroom, shortly before the Americans boarded.

Rather than seize the Trent as a prize, as is custom in such situations, Wilkes let her go, explaining at a later date that he didn’t want to inconvenience the passengers or interfere with British trade. With the envoys stowed safely aboard the San Jacinto, Wilkes sailed for Union waters.

Finding the Words

The American public learned of the Trent incident on November 16, when reports began appearing in newspapers. After the Union disaster at Bull Run, the North was hungry for a victory against the South and the Trent incident seemed to offer a small one. Within days, Wilkes was feted as a hero as legal scholars declared his actions within the boundaries of international law. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles was thrilled with the news, but wondered if failure to seize the Trent set a bad precedent. Seward wanted to lock up the prisoners and throw away the key. The House of Representatives passed a resolution thanking Wilkes for his “brave, adroit and patriotic conduct in the arrest and detention of the traitors.”

Not everyone in Washington found joy in the news. President Lincoln and Charles Sumner, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, worried that Wilkes’s actions spelled trouble for the Union’s relations with Britain.

For Lord Lyons, the British minister to Washington, it meant his greatest fear had come to fruition. “I have all along been expecting some such blow as the capture on board the Trent,” he wrote Russell. “I am so worn out with the never-ending labour of keeping things smooth, under the discouragement of the doubt whether by so doing I am not after all only leading these people to believe that they may go all lengths with us with impunity that I am sometimes half tempted to wish that the worst may have come already.”

“The worst” was open conflict, or even war, with Britain. All would depend on Britain’s response.

In 1861, the transatlantic cable wasn’t operational, which meant it took two weeks for the news to reach Britain, and when it did the London newspapers went mad. The London Morning Post predicted a rapid victory: “In one month, we could sweep all the San Jacintos from the sea, blockade Northern ports, and turn to a direct and speedy issue the tide of the war now raging.”

The American embassy learned of the incident on November 27. In Yorkshire visiting a friend, Adams rushed back to London, only to find that Seward had sent no instructions. When the British government entered its deliberations on November 28, Adams had nothing to offer.

“What part is reserved to us to play in this very tragical comedy I am utterly unable to tell. The Government has left us in the most awkward and unfair position,” wrote Henry. “They have given no warning that such an act was thought of, and seem almost to have purposely encouraged us to waste our strength in trying to maintain the relations which it was itself intending to destroy. I am half-mad with vexation and despair.”

Like many Britons, Lord Palmerston regarded the Trent incident as an affront to Britain’s honor. He famously opened the emergency Cabinet meeting by tossing his hat on the table and declaring, “I don’t know whether you are going to stand this, but I’ll be damned if I do!” Palmerston’s disdain for the United States ran deep. He had welcomed the advent of the Civil War because of the prospect of the Union permanently dissolving. But he wasn’t the only one ready to fight. Others in the Cabinet believed that war was inevitable, with both the Duke of Argyll and Lord Stanley blaming American hubris for the current crisis.

Not everyone in Britain was for war. The opposition leaders—Liberals Richard Cobden and John Bright—didn’t believe the Union wanted one. It didn’t make sense that the Union would intentionally start a war, as many in Britain were charging, while fighting one on its own soil. “The accusation is so utterly irrational that it would be regarded as a proof that we want to take advantage of their weakness and to force a quarrel on them,” wrote Cobden.

As the Cabinet crafted a response, it lacked a key piece of information: Did the Union order the seizure of the envoys or did Wilkes do it on his own? Reports varied and the Union failed to provide any clarification. The Cabinet, therefore, focused on what it did know: Wilkes didn’t take the Trent as a prize. By not doing so, he violated international law and owed reparations. After a cantankerous debate, the Cabinet decided to issue an ultimatum: The Union had one week to release the prisoners, or else.

On the night of November 29, the dispatch summarizing the Cabinet’s position was delivered to Queen Victoria for approval. Unhappy with the belligerent tone, her husband and consort, Prince Albert, rose from his sick bed to redraft the dispatch, taming the language and offering the Americans a way to save face. The dispatch, which left for Washington on November 30, is considered the Prince’s last great service for the Crown. He died two weeks later, after succumbing to typhoid.

This War Will Begin in 7. . . 6 . . . 5 . . . 4 . . .

As Britain’s ultimatum sailed across the Atlantic in early December, the Cabinet made preparations for war. The Caribbean fleet was increased from twenty-five to forty warships, and the British troop presence in Canada was boosted from 5,000 to more than 17,000 men. If the Americans refused to cooperate, Britain would be ready to fight.

Adams, meanwhile, still had no instructions from Seward. He took to dodging Russell rather than having to confess, yet again, that he hadn’t heard from Washington. Henry felt for his father’s predicament. “I wonder what Seward supposes a Minister can do or is put here for, if he isn’t to know what to do or to say. It makes papa’s position here very embarrassing, and if he were to see Lord Russell coming along the street, I believe he’d run as fast as he could down the nearest alley.”

In mid-December, Lord Lyons received his instructions from the Foreign Office. While waiting for guidance, Lyons had avoided broaching the subject with Seward, resulting in a cordial, but high-stakes standoff. In a private letter that accompanied the formal instructions, Russell wrote that the dispatches “which I have signed this morning impose upon you a disagreeable task.” Russell believed that if the Confederate envoys were released and allowed to continue their journey to England, and an apology was given through Adams in London, Britain would consider the issue settled. “But if the Commissioners are not liberated, no apology will suffice. . . . The feeling here is very quiet but very decided. There is no party about it: all are unanimous.” The Americans had seven days to comply. If they failed to do so, Lyons was to sever diplomatic relations.

The dispatch that Lyons was instructed to share with Seward—the one redrafted by Prince Albert—is a marvel of diplomatic prose:

Her Majesty’s Government, bearing in mind the friendly relations which have long subsisted between Great Britain and the United States, are willing to believe that the United States’s naval officer who committed this aggression was not acting in compliance with any authority from his Government, or that if he conceived himself to be so authorized, he greatly misunderstood the instructions which he had received.

For the Government of the United States must be fully aware that the British Government could not allow such an affront to the national honour to pass without full reparation, and Her Majesty’s Government are unwilling to believe that it could be the deliberate intention of the Government of the United States unnecessarily to force into discussion between the two Governments a question of so grave a character, and with regard to which the whole British nation would be sure to entertain such unanimity of feeling.

Britain gave the Union an opening to foist all blame for the Trent incident on Wilkes, whether guilty or innocent.

Knowing that once he shared the dispatch, the clock would start ticking, Lyons had an informal chat with Seward about the terms. When Seward asked if it came with an ultimatum, Lyons admitted that one existed, prompting Seward to beg for a copy of the dispatch. “So much depended upon the wording of it, that it was impossible to come to a decision without reading it,” said Seward. Lyons agreed to give him a copy provided its substance remained between Seward and Lincoln. Within minutes of its delivery, Seward appeared in Lyons’s office. “He told me he was pleased to find that the despatch was courteous and friendly, and not dictatorial or menacing,” wrote Lyons.

The clock officially started ticking on December 23. Lyons expected to have an answer by the end of the seven days, but had little inkling of which way the Americans would go. “There is no doubt that both government and people are very much frightened, but I still do not think that anything but the first shot will convince the bulk of the population that England will really go to war.” In London, Russell was more optimistic, telling Palmerston, “I am still inclined to think Lincoln will submit, but not till the clock is 59 minutes past 11.”

On Christmas Day, Lincoln called a meeting at ten o’clock in the morning to discuss options. The question confronting Lincoln and his cabinet was, Could the Union afford to go to war with Britain? The war with the South wasn’t going well. A break with Britain over the Trent incident would likely lead to Britain supporting the South, which would be a disaster for the Union. Britain’s response to the incident also went beyond diplomatic posturing. Additional troops were already en route to Canada and reports from London suggested that the British public’s support for war against the United States had not wavered. A letter from Adams reported that “the leading newspapers roll out as much fiery lava as Vesuvius is doing, daily. The Clubs and the army and navy and the people in the streets are generally raving for war.”

There was another aspect to consider. The Union obtained most of its saltpeter, the primary ingredient in gunpowder, from India, a British colony. During the fall, a Union agent secretly bought every bit of the mineral he could find in Britain. Five ships loaded with 2,300 tons of saltpeter were ready to weigh anchor, but when news of the Trent incident arrived, the British government embargoed the ships. They would be released only after the Trent incident was resolved. The Union couldn’t fight a war without saltpeter.

At a dinner at the Portuguese legation, Seward boasted through a fog of brandy and cigar smoke, “We will wrap the whole world in flames!” By the time of the Christmas meeting, however, he had come around to supporting the release of Mason and Slidell. Sumner pressed for conciliation as well. Lincoln, however, remained opposed.

The cabinet met again the following day. After four hours of discussion, it recommended that Mason and Slidell be released, to which Lincoln raised no objections. Surprised by Lincoln’s change of heart, Seward asked the president what had inspired it. He is reported to have answered, “I found that I could not make an argument that would satisfy my own mind, and that proved to me your ground was the right one.”

When confronted with whether to go to war with Britain, Lincoln is famously said to have uttered, “One war at a time.” While there was plenty of reason for the Lincoln administration to be exacerbated by Britain’s decision to remain neutral and her handling of the Trent incident, the Union needed all of its resources to defeat the Confederacy. A two-front war would have spelled disaster for a Union war effort that had not yet found its footing.

On December 27, Seward delivered a bombastic twenty-six-page letter cataloging every aspect of the case and the Union’s just response. He also blamed Wilkes for failing to take the Trent as a prize. Having said his piece, he ended the letter by telling Lyons that Mason and Slidell would be “cheerfully liberated.” Lyons merely had to indicate a time and place for receiving them.

“Those who have not seen the Americans near, will probably be much more surprised than I am at the surrender of the prisoners,” Lyons wrote Russell. “I was sure from the first day that they would give in, if it were possible to convince them that war was really the only alternative.”

The “Trent affair passed like a snowstorm, leaving the Legation, to its surprise, still in place,” wrote Henry Adams. The “crisis of his diplomatic career” had died with a whimper. While the Union and Britain continued to quarrel over the course of the Civil War about the blockade, trade, and the Confederacy, disagreement never again pushed the United States and Britain to the brink of war. The bonds bred by the crisis also served both countries well. Seward and Lyons had taken the measure of each other in Washington, while Adams and Russell formed a congenial working relationship in London.

Davis’s dream of having Britain recognize the Confederacy also died with the Trent incident. Upon their release, Mason and Slidell made the journey to London and Paris, but couldn’t make any headway diplomatically. Britain continued its neutral stance throughout the war, and the Confederacy found it had few friends in Whitehall.