In 1966, Eric Carle designed a full-page advertisement for Chlor-Trimeton Repetabs that featured a lobster and the caption “When yesterday’s indulgence becomes today’s allergy.” Carle had yet to illustrate a children’s book, but the tissue-paper collage lobster might have crawled from the pages of one of his future best-sellers, inhabiting the ocean floor in Mister Seahorse or answering a child’s cry of “Lobster, lobster, what do youhear?”

Bill Martin Jr. saw immediately that the lobster was born to be in books. He asked Carle to illustrate Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?—their first collaboration and Carle’s earliest foray into children’s books.

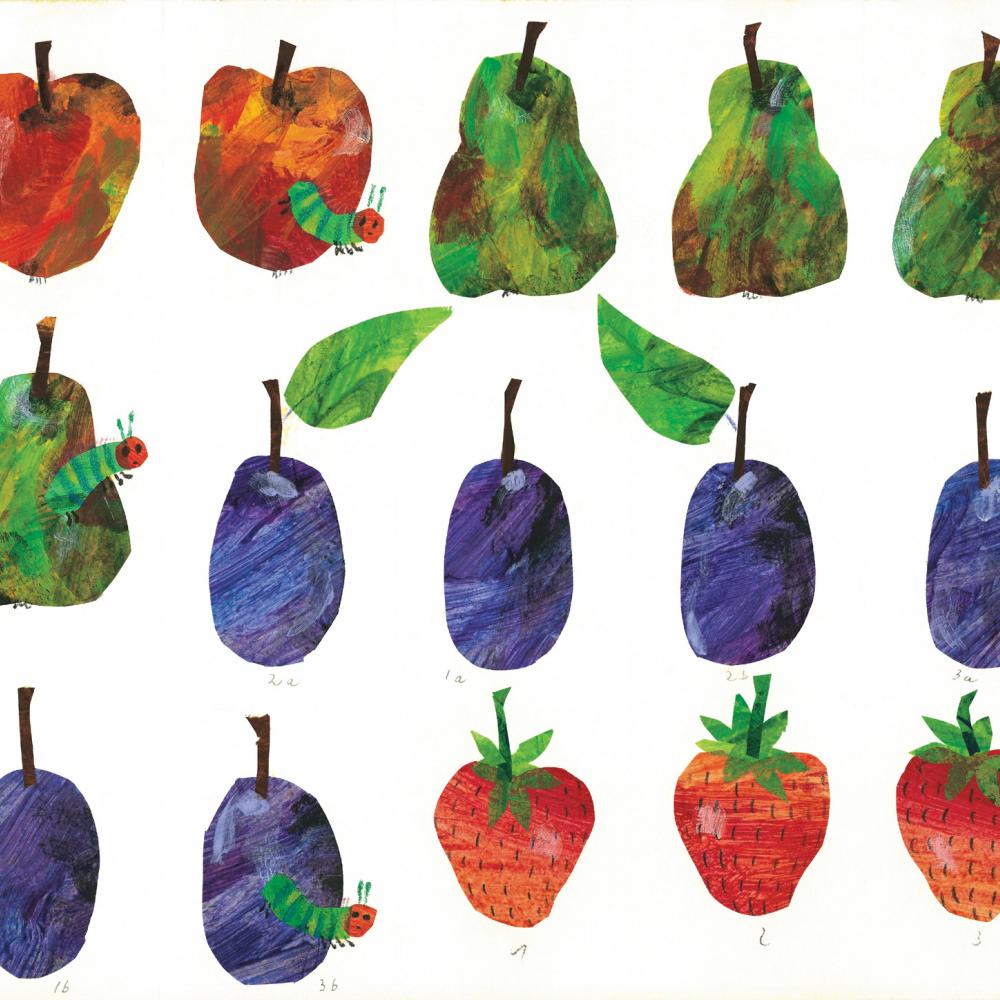

The lobster is one of the earliest instances of food imagery in Carle’s work. Eric Carle’s food illustrations are the subject of the exhibit “A Feast for the Eyes,” which runs through March 20 at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, with support from Mass Humanities.

Nearly everyone is familiar with The Very Hungry Caterpillar and his Saturday romp through junk food. Fewer people know that the caterpillar grew out of another food-related project. In the mid sixties, Carle worked with editor Ann Beneduce on a cookbook, Red-Flannel Hash and Shoo-Fly Pie, which he illustrated using simple linoleum block prints. The strong, elemental shapes of those prints echo in his tissue-paper collages of today.

Sensing a receptive mind, Carle approached his editor with an idea for a children’s book—a bookworm who overeats. Beneduce doubted the appeal of a worm and suggested a caterpillar. Carle instantly foresaw the transformation into a butterfly, and the book was born.

One of the curatorial team’s challenges was toning down the presence of the famous caterpillar (he appears only twice in the exhibit, in the twenty-fifth and thirtieth anniversary commemorative posters) to make way for less familiar images. The exhibit comprises mainly illustrations from four lesser-known books, Walter the Baker, Pancakes, Pancakes!, My Apron, and Today Is Monday, in which children enjoy a different food each day of the week.

The first image is Carle’s author photo from Walter the Baker. Carle—looking like a lean Santa Claus—wears a tall chef’s hat and chef’s uniform. He holds a whisk, prepared to whip up a skillet full of the hand-painted tissue papers he uses to construct his bright-colored collages. “I have always fantasized about being a chef,” Carle writes in an e-mail.

If you’re lucky enough to be invited to the Carles’ Florida home, he’ll cook you pancakes, says the museum’s chief curator, H. Nichols B. Clark. Pancakes bridge the gap between Carle’s own childhood and his audience’s. In Pancakes, Pancakes!, a young boy, hair askew in triangular wedges, legs bare beneath vivid green and blue pajamas, tells his mother, “I’d like to have a big pancake for breakfast.” Carle writes, “During the war, when I was a child, food was scarce and pancakes were a meal my mother could make out of simple ingredients. One egg, a cup of flour, and so forth. . . . And even though it was simple, a pancake was a special treat.”

My Apron is less obviously a food book than the others. The exhibit’s original illustration from My Apron depicts a boy (Carle) having lunch with his Uncle Adam. But My Apron is about building construction, and its history is intertwined with the museum’s, says Clark. When construction workers placed the last steel beam in the museum, staff members presented them with copies of My Apron as a gift.

In a departure from Eric Carle’s signature style, My Apron pays homage to Fernand Léger, a modernist French artist. Writes Carle, “I outlined the figures with a heavy black line, then superimposed it over the colorful collage. It makes the pictures bolder, stronger, the kind of pictures that should be in a book about working people.” A print of Léger’s Le Cycliste hangs in the exhibit to emphasize his influence: black, curvy, cubist outlines of man and bike starkly superimposed over simple shapes in mostly primary colors.

The exhibit, one of several at the museum, is small, but young museum goers can hunt through the gallery for food images from A to Z—apron, blueberry, chickens, and so on. In the museum’s arts-and-crafts studio, open whenever the museum is, educators hand children a paper plate, a napkin, and a spoon and invite them to improvise with glue and a rainbow array of crafts materials. There’s also a research library stuffed to the gills with children’s books.

Although the museum is cleverly tailored to amuse children, it’s a mistake to dismiss this as just a children’s exhibit. Of course, food has an incredible power over most, if not all, children. But it has an even greater power over adults, as Carle himself hints when he reminisces about his Uncle Walter, the inspiration for Walter the Baker. “I do remember visiting my uncle at his bakery when I was a boy. . . . I still love going to bakeries and smelling that scent of fresh bread when you first walk in,” Carle writes. It’s that power, to return us, swiftly and primitively, to childhood, that Carle harnesses and the museum named for him celebrates.