A little more than a century ago, admitting that one was addicted to alcohol or drugs was akin to confessing to a horrible crime. Addicts existed on the margins of society, either shunted off to asylums for inebriates or banished to prisons where they rarely received help for their addictions. Today, the range of treatment facilities and therapeutic options for addiction are immense, and our collective fascination with addictive behavior remains: What makes the addict tick? Is it possible to change?

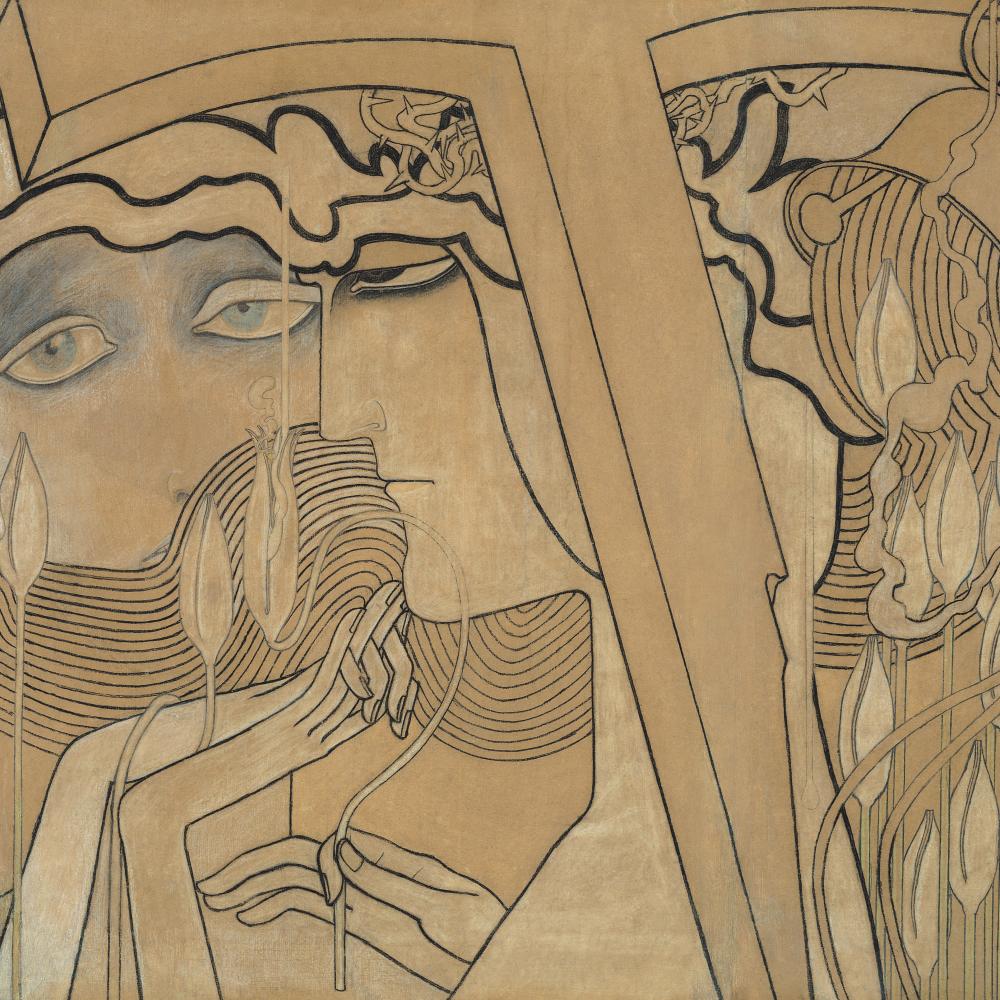

Such questions have fascinated readers since Thomas De Quincey’s 1821 memoir, Confessions of an English Opium Eater, first offered descriptions of the author’s fantastical cravings for “the divine luxuries of opium.” After a friend of Leo Tolstoy’s regaled him with stories of the American Temperance movement, Tolstoy denounced both alcohol and tobacco use in his 1891 essay “Why Do Men Stupefy Themselves?”—and eventually gave up both substances in his quest for spiritual enlightenment. In these and other nineteenth- and early twentieth-century accounts, addiction is described as a moral and spiritual problem, one that could only be overcome by eschewing the addictive substance and committing oneself to a higher authority—namely, God. Once renewed, a person could reinvent himself. In the American popular imagination, the possibilities for reinvention and renewal have also long been linked to relocation, whether moving from town to city, or, in the nineteenth century, heading west. Mobility effectively erased the stigma that might otherwise linger over a former addict. He could simply leave town.

Today, an increasing number of addicts and former addicts are as eager to describe their experiences as to escape them. Narratives of addiction and recovery dominate all forms of media: reality television shows, such as Celebrity Rehab and Sober House, follow celebrities in recovery, while the documentary-style show Intervention tells the stories of ordinary people seeking treatment for drug and alcohol abuse. Memoirs of addiction are now a staple of nonfiction publishing. Recently, the “Vows” column in the New York Times featured a couple who, in addition to discussing the details of their courtship and marriage, also described their long struggles with alcohol and drug use. If print media is any guide, the list of new addictions with which Americans struggle grows annually and now includes sex, food, shopping, Internet use, clutter, and gambling.

But as Trysh Travis’s The Language of the Heart: A Cultural History of the Recovery Movement from Alcoholics Anonymous to Oprah Winfrey reminds us, although we are steeped in the language of recovery, we know little of its history. Her study of one of the earliest and most successful treatment programs, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), offers an intriguing examination of how a culture’s notion of a vice (and a sign of individual moral failing) can, over time, change, and see it as merely a regrettable and treatable disease.

AA began in 1935 amid the challenges of the Great Depression. One of its founders, Bill Wilson, had unsuccessfully struggled with his own alcoholism for years; both Wilson and his cofounder, Dr. Bob Smith, had been involved in a non-denominational Christian fellowship called the Oxford Group which according to AA’s own history, “practiced a formula of self-improvement by performing self-inventory, admitting wrongs, making amends, using prayer and meditation, and carrying the message to others.” The Twelve-Step program that emerged from Wilson and Smith’s conversations in the 1930s became the basis for the AA program, whose preamble described it as: “a fellowship of men and women who share their experience, strength and hope with each other that they may solve their common problem and help others recover from alcoholism.” AA does this by encouraging alcoholics to attend regular meetings with other AA members to talk about their struggles, providing them with a “sponsor” who has successfully navigated the AA program, and, as Travis shows, sustaining a thriving print culture of books and pamphlets aimed at helping people conquer addiction.

Since the organization’s founding, it has grown to nearly two million members worldwide, and its twelve-step program has helped countless addicts and spawned many imitators. AA has helped well-known people such as astronaut Buzz Aldrin and film critic Roger Ebert, and for decades has been featured in films such as Something to Live For (1952), Days of Wine and Roses (1962) and When a Man Loves a Woman (1994). We all likely know someone whose efforts at sobriety have been aided by the twelve-step model. Although he never attended AA meetings, former President George W. Bush, in a 1999 Washington Post interview, credited AA’s philosophy, particularly its emphasis on trusting in God, for helping him to stop drinking. It remains one of the most effective addiction treatment programs in the world.

And yet, one of the more interesting aspects of Alcoholics Anonymous is how quaint the organization’s insistence on anonymity now seems. Recovery from addiction is today viewed less as an embarrassing common problem than an individual journey—in part because of AA’s success in destigmatizing alcoholism. Recovery from addiction is so acceptable that it has become a cultural commodity that can be parlayed into an equally addictive kind of pseudo-celebrity on television and in print.

This transformation is striking when one compares contemporary recovery narratives, which are emotionally promiscuous and unabashedly revealing in tone, with earlier stories of addiction, which often began with a preemptive apology from the author. In his effort to be “useful and instructive” about his opium addiction, for example, De Quincey offered an “apology for breaking through that delicate and honourable reserve, which, for the most part, restrains us from the public exposure of our own errors and infirmities.” He acknowledged that nothing was “more revolting to English feelings, than the spectacle of a human being obtruding on our notice his moral ulcers or scars, and tearing away that ‘decent drapery,’ which time, or indulgence to human frailty, may have drawn over them.” Few remnants of De Quincey’s “decent drapery” can be found in contemporary recovery narratives. James Frey’s now-discredited addiction memoir, A Million Little Pieces, which suffered from an unapologetically childish tone throughout, included elaborate descriptions of the crude things he wanted to do to the recovery literature he read during his stint in rehab.

As a culture, we also nurture expectations about the direction recovery narratives should take, namely, the swift and dramatic transformation of the offending addict. On television shows, this is known as The Reveal—the moment in the broadcast when the addict finally admits his or her addictions and vows to change—and it is the dramatic peak of the program. In print, the narrative arc moves from despair, to hope, to eventual renewal and recovery, and it is the modern expression of our culture’s long-standing fascination with personal reinvention, a skill perfected by nineteenth-century entertainer P. T. Barnum, who published multiple versions of his autobiography, each tailored to suit the particular needs of his audience at the time.

Today, addiction is yet another thing we are supposed to overcome on the road to personal transformation. This optimism about the ability to change your life is a recurring theme in American culture; it is the reason you will always find a well-stocked self-help section in every American bookstore. We have come to expect the reassuring language of therapy in nearly all aspects of our lives, from the automated message that “your time is valuable to us” we hear when we’re holding on the phone to the uplifting bromides that appear on the side of every Starbucks latte we order.

This expectation is perhaps clearest when it comes to public figures. As Travis notes in her book, political commentary during the Clinton and George W. Bush years often invoked the language of addiction and therapy to shape its narrative: “Critics on both the left and the right talked about the Clinton and Bush regimes in terms of addiction and recovery, and recovery-inflected readings of the two presidencies appeared in the most respectable media outlets,” she writes, even though this did not always have an edifying effect on political discourse. So, too, when a public figure finds himself enmeshed in scandal, we expect him not only to apologize for his conduct, but also to discuss his plans for therapy and his ongoing devotion to recovery, as golfer Tiger Woods did after being exposed for his extramarital affairs.

For critics of this therapeutic sensibility, it is worrisome when a culture’s narratives of recovery focus more on personal fulfillment than personal discipline; when we want more Eat, Pray, Love and less Epictetus, for example. Several decades ago, in one of the more blistering attacks on the culture of recovery and its therapeutic sensibility, Christopher Lasch wrote in The Culture of Narcissism: “People today hunger not for personal salvation, let alone for the restoration of an earlier golden age, but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being, health, and psychic security.” For this, they turn not to their priests but to their therapists, “in the hope of achieving the modern equivalent of salvation, ‘mental health.’” Lasch was especially critical of the quasi-spiritual language invoked by those who hawked therapy to the masses, and he likely would not have been impressed with contemporary gurus like Eckhart Tolle, whose philosophy is renowned not for its intrinsic worth but for the fact that its diminutive promulgator regularly appears on the Oprah Winfrey Show.

If a key metaphor of nineteenth-century American culture was reinvention through geographical transplantation, a central premise of the twentieth century was recovery through inner transformation. What does the future hold? In a culture where self-incrimination has become the backbone of popular culture, and where we can easily broadcast, track, and tag our every behavior with ironic enthusiasm, there is an even greater need than before for the genuinely earnest tenets of movements such as Alcoholics Anonymous. They challenge people to look inward, not to wallow in self-pity or to mine their inner lives for public consumption, but simply to change their behavior for the better. As AA’s rather mundane motto, “One day at a time,” suggests, this is hardly the stuff of sensationalist narrative. But for many people, it is the one thing that offers hope for honest transformation and a better life.