Gale Peterson’s plan to teach high school history had one fatal flaw. Not his B.S. in History and Government from Iowa State University. Not his master’s degree and doctorate from the University of Maryland. Not his work as a researcher for the Smithsonian Institution’s Living Historical Farms project.

“I couldn’t coach football,” Peterson says with a chuckle. “I don’t know how I thought I could teach high school history when I couldn’t coach athletics.”

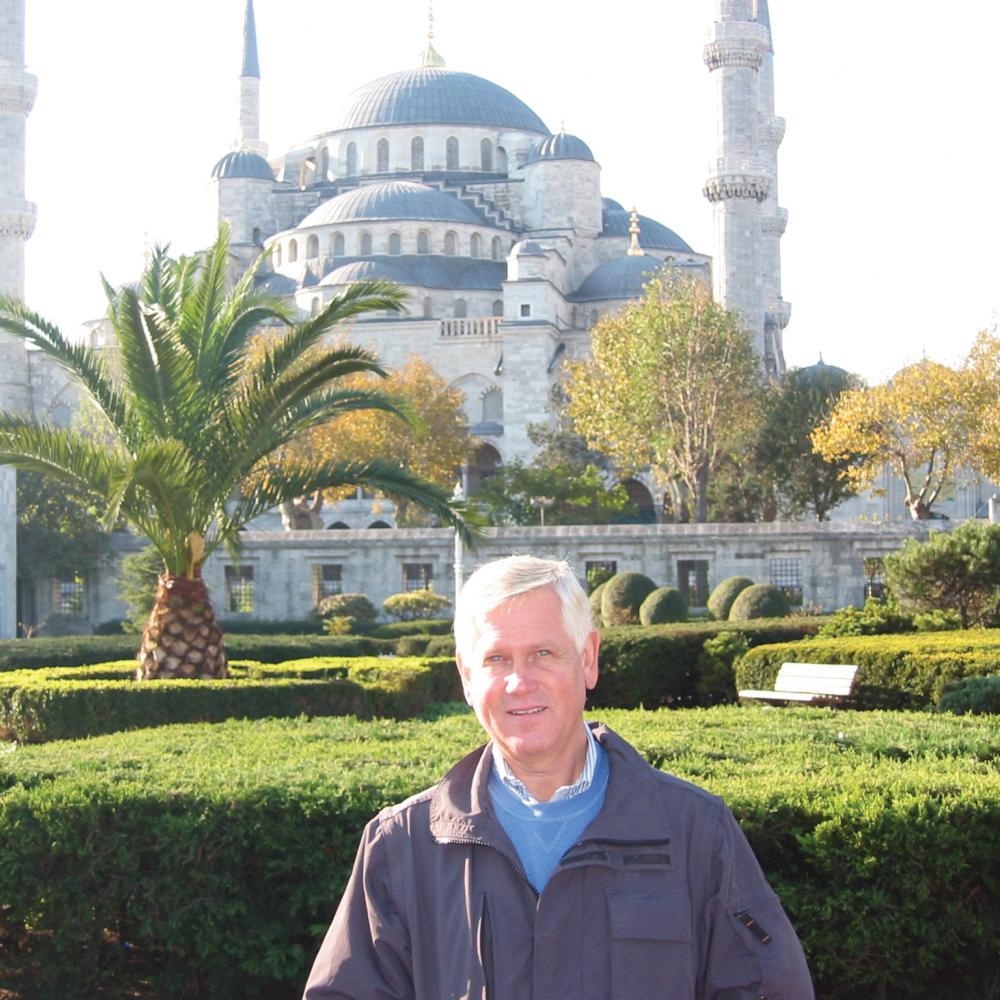

Instead, Peterson embarked in 1973 on a career in the museum world that culminated in the job he has held for the last thirteen years: director of the Ohio Humanities Council.

“I have always loved history since I was a boy growing up in Iowa,” Peterson says. “And as I grew older I recognized that history was important, yes, but that it also needed to be taught well.”

Peterson first worked at the Organization of American Historians, where he helped conceptualize what became the NEH’s United States Newspaper Program.

In 1978, he began his life’s work of “making history more accessible to the people” when he became executive director of the Cincinnati Historical Society. He held the job for nearly two decades before leaving for the Ohio Humanities Council.

Peterson has a passion for making the humanities “accessible to a wider audience” and “bridging the gap” (between scholars and the general public). That’s why he points to the council’s Ohio Chautauqua program as one of his defining endeavors.

“So often scholars speak only to their peers,” he says. “A typical historical monograph might have a press run of only five hundred copies. I appreciate the historian’s work. Documentaries and television programs couldn’t exist without the historian’s spadework. I think part of our job is to distribute that work, to create ways to engage people beyond the monograph or the classroom. We want to celebrate history, but also help people analyze it. We’re the context people.”

The Chautauqua, a staple during Peterson’s tenure at the council, is a five-day traveling tent show held in Ohio towns and featuring scholar-actors who assume the roles of historical figures. The most recent Chautauqua included first-person historical portrayals of W. C. Fields, Margaret Mitchell, Paul Robeson, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Orson Welles.

“The Chautauqua is living history,” Peterson says. “And because we take the Chautauqua to towns like Archbold and Gallipolis and Cambridge, we’re able to raise our profile throughout the state and reach into places that wouldn’t normally have access to this sort of entertainment and history.”

One of Ohio’s greatest strengths is also one of Peterson’s greatest challenges: its remarkable diversity.

“Is there an Ohio?” Peterson wonders. “People in Youngstown and Cleveland hardly know Cincinnati exists. People in Toledo don’t think they have much in common with Ohioans living in Appalachia. There are eight distinct media markets. It’s complicated.”

Not like Iowa, where Peterson spent his childhood.

“I grew up in Marathon, Iowa, about a hundred and fifty miles away from the state capital, but the Des Moines Register was our hometown newspaper. We were all Iowans in a way that’s not true in Ohio,” he says.

“When we look at our state as Ohioans, we don’t see it as a whole. But it’s such a rich state for its history, for its role in the Civil War and ending the institution of slavery, in the civil rights and the labor movements.”

Peterson said he’s also proud of the council’s oral history workshops, taught by scholars from Ohio and the Midwest and held every summer for eleven years on the campus of Kenyon College in Gambier. Out of the workshops came the book Catching Stories: A Practical Guide to Oral History, published by the Ohio University Press in 2009. Booklist praised Catching Stories for creating “a compelling context for recording the stages of one’s life.”

“We teach interviewing and transcription and the ethics of oral history,” Peterson says. “When you’re conducting oral history you’re in a sense an informant, and we teach neutrality. We really take novices and give them professional standards so that they can create oral history at the highest standards.”

Though he didn’t fulfill his dream of teaching high school history, Peterson has no regrets. All of his jobs in history have been interesting and provided the kid from Marathon an opportunity to see the country and then the world. “I’ve been able to make some good things happen.”