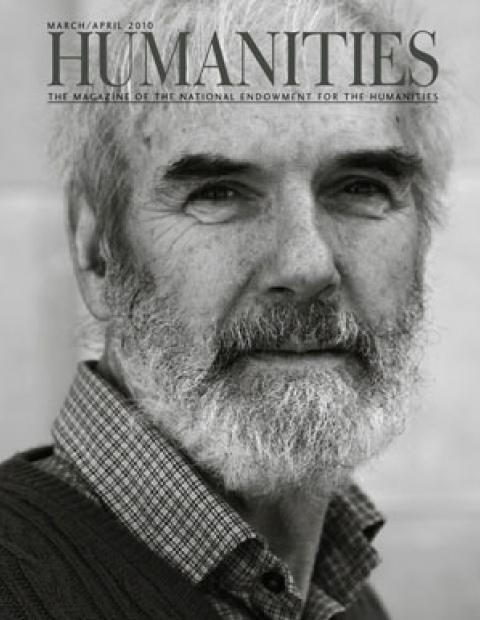

JIM LEACH: You were born in Surrey, England, attended Winchester College and then Clare College, Cambridge. You showed a literary bent, studied European history, and came to Yale to study. Then you switched to Chinese history. Why?

JONATHAN SPENCE: Well, it’s probably one of the most complicated decisions I’ve made. It wouldn’t have happened, as far as I can tell, unless I had gotten an exchange fellowship to the United States. I had never really studied Asia, except peripherally where it happened to impinge on British imperial history.

In 1959, I got offered a two-year fellowship to do a master’s degree. It was a program funded by Paul Mellon, a loyal Yale graduate and donor who endowed this fellowship for English people, specifically from Cambridge. This gave me a chance to sample Yale’s curriculum. I won’t weary you with the different attempts I made to see which subject needed studying the most, and I found there were too many for me to make a logical decision.

In the summer of ’59, two wonderful China scholars had joined the Yale faculty, Arthur Wright and Mary Wright. My quite fortuitous arrival coincided with their coming to New Haven.

While talking to them, I suddenly thought this would be fun to explore. So I plunged into the equivalent of Chinese History One and Basic Chinese Language One and got fascinated by this completely different history, and I’ve stayed with it. That’s the serendipity of it all.

LEACH: When one thinks of Chinese history, one thinks of dynasties. And in British history, one thinks of kingships. Did that analogy help you?

SPENCE: I think the dynastic structure was of a more complex scale than the more rapid changes in rulership in British history. In terms of comparative study, there wasn’t much made of that.

In the late fifties and early sixties, the area of comparative study that interested me was between the gentry or the intellectual elite and landowning, which you did find in China and in the United Kingdom. We can look at how this group was educated and how from being educated, in the Chinese case, they took over governance. In England, advancement turned out to be more directly based on landholding.

We could look at different lifestyles—different education patterns, marriage patterns, child-raising patterns. I remember finding that fascinating. It was a true linkage of the social sciences with the humanities that dominated much thought about China in the early 1960s.

LEACH: When did you first visit China?

SPENCE: I was in Taiwan back in 1963; I didn’t go to mainland China until 1974, two years after President Nixon’s visit. I’d also been in Hong Kong, which then was still controlled by the British.

My research into archival material was initially done in Taiwan. In those days, with the threat of war being discussed both in mainland China and in Taiwan, the documents were kept in air-raid shelter conditions.

One needed a complex series of introductions to get at them. I was lucky to get an introduction to a curator of what became the National Palace Museum in Taiwan and was able to do some research into imperial documents of the early Qing rulers of the seventeenth century, the people who became my favorite subjects of study.

I was able to hold in my hand the original writings of the emperor of China. It was something that is still very emotional for me, and it was a major moment for my thinking about the past.

LEACH: The prior generation of American Chinese scholarship was symbolized probably by John King Fairbank. One has a sense of a man who was deeply motivated by influencing and training people who would be part of foreign policy making. Was that instinct ever part of your nature?

SPENCE: I knew Professor Fairbank quite well. He was a formidable presence, and he could be very gracious to younger scholars. In fact, Mary Wright, who became my dissertation director, had done her dissertation under Fairbank. So, in a sense, I was sort of his grandson. And Arthur Wright had also studied the history of China at Harvard, working in earlier Chinese history and Chinese Buddhism. Mary Wright had studied the great rebellions of the nineteenth century and the way China had tried to hold together under foreign pressure.

Neither of them had the specific agenda that John Fairbank had. And they didn’t have the same entrepreneurial interest in making an enormous center at Yale. They were concentrating more on having a tightly run center in which there would be a balance between early modern history, early and modern religious studies, language, literature, and art history.

LEACH: You mentioned Mary Wright and her interest in nineteenth-century rebellions, one of the most interesting being the Taiping rebellion. Americans are not particularly aware that something occurred that might have been a larger civil war than our own. One is struck by the fact that the leader of the uprising was influenced by the teachings of Western missionaries. And so, you have an example of a Western cultural impact on the course of Chinese revolutionary movements. Do you consider that a significant event in terms of how Chinese look at the West today and worry about groups like the Falun Gong?

SPENCE: It remains something deeply worth thinking about. Mary Wright’s first book was called The Last Stand of Chinese Conservatism. And that gives us, perhaps, a sense of where she was going.

She was interested not just in this group called the Taiping and their revolutionary aspects or in their Christian aspects, which, by the way, some people say were not very deep. Others say it ran extremely deep in the Taiping—they had studied with foreign missionaries, usually fairly informally, and some of the leaders certainly knew the main outlines of Christian doctrine.

But Mary Wright’s main interest was how the state coalesces again after a colossal civil war and an internal rebellion that led to fifteen to twenty million casualties. This enormous loss of life ended in 1864, and the ruling elite was able to reestablish itself for another forty-five years of imperial rule. Was there a valid tradition of Chinese conservative thinking that could be linked to the bureaucracy and the examination system to the practical skill that allowed the ruling elite to reestablish itself after the rebellion?

What Mary Wright tried to understand was the toughness that came with this education that enabled a country to pull together when it had really been in danger of total disintegration.

The Taiping rebellion was only one of four rebellions that struck China in the 1860s and 1870s. The scale of the disaster and the chaos that was caused certainly exceeded that of the American Civil War.

But Mary Wright had a broader agenda there, which was looking at the structure of the later political parties. And by jumping forward in time from that study of the suppression of the rebellion and the reassertion of central power, Mary Wright took a parallel look at the Nationalist party of China controlled by Chiang Kai-shek and its claim to have a conservative background.

So this was not without political implications, especially during the Cold War. Mary Wright’s book had, I think, a real influence in broadening our thinking about the linkage of past catastrophe and present regimes and meant that we were encouraged to take a broad look at Chinese nationalism.

We should remember the title of her book. It wasn’t just that a new kind of dramatic conservatism was going to win in China. If there had been a last stand of Chinese conservatism, the title implied that it was over. We were now going to have to deal with a completely new, different kind of regime. And you could argue, if you wish, that we’re still doing just that.

LEACH: What drew you to write about the Italian Jesuit cartographer Matteo Ricci?

SPENCE: Ricci wrote in the late sixteenth century and into the early seventeenth, presenting a portmanteau of Western values and religious experience of different kinds. He represented the cutting edge of Jesuit Counter-Reformation forces, the reassertion of Catholic power and influence.

It was the period of the second to last dynasty, the Ming dynasty, which collapsed after a swift, but massive civil war. And this meant that China was again dislocated. This dislocation coincided with the arrival of particularly skillful Jesuit scholar missionaries. And Ricci was one of them.

He’s one of the most interesting people I’ve ever studied, and it took me some time to write about him because he was awesomely complicated and a man of great subtlety. I didn’t want to mess around with the record until I felt a little more confident that I could understand him, read his original journals, and get some sense of what he was trying to do in China and why Chinese scholars around the year 1600 would have cared what a Westerner thought.

We take it for granted that, of course, they were interested in us. But why? Why, when they had this huge tradition of their own and their own bureaucracy, their own religion, their own cartography, their own sense of time and place, their own sense of geography? All of these are areas Westerners claim to have a superior knowledge of. And yet the Chinese were doing extremely well. So the mystery can be rephrased. What was it that the Jesuits called upon in order to attract Chinese elites to share a Western religious system and the social values that went with it?

This led me in every conceivable direction—the nature of prayer and the nature of conversion, the nature of a pastoral elite in China, the relationship of the Chinese experience with Buddhism or Taoism, to which now was added Christianity and into which Islam and Judaism had already been partially incorporated.

So China was a cross section, if you like, of mosques and churches and temples and shrines. Because of their intellectual power and their willingness to learn the Chinese language, the best of these Western missionaries developed an ability to preach and teach in Chinese, whether they were from Italy or Portugal or Spain or France.

In Ricci’s case, he made an astonishing jump. He was able to write books in Chinese after he had been in China for six or seven years. And that’s still something most of us would not have any chance of doing, really, to write an elegant book on Western religion in Chinese and circulate it in China. That would be rare. So Ricci was a major pioneer.

LEACH: We have this idea of cultural exchanges, which might better be described as cultural elbowing.

SPENCE: Cultural elbowing? That’s a very nice phrase.

LEACH: Did the various Westerners in China have shared themes and common understandings or misunderstandings?

SPENCE: That’s an important question. It was important in the period just before the Korean War. And it’s important in the opening up of China and the post-Maoist period. And it’s important now.

The phrase “closed China” has sometimes been used. It was extremely difficult to work and live in China without permission from the government. And as Western powers got more assertive and were more able to impinge on China, they got more and more frustrated by the Chinese attempt to stop this from happening.

I was intrigued by this long ago. I wrote my second book, which I called To Change China, on this idea—the ongoing quest for transforming a society into a mirror image of Western society.

By connecting the dots from the Jesuits right through to the Russian and American technical advisers, one could frame a sort of longitudinal study in which we can see at least some of what the West was trying to impose on China.

This was a really complex patterning. And I didn’t want to oversimplify it. But in broad outline, you can see a strong lay missionary impetus among Westerners, not just a religious impetus, but laymen or laywomen using aspects from Western culture to change China in what they thought was the direction it ought to be going.

Now, to do that is an extremely dangerous thing. It’s part of foreign policy in many periods of time. But this was almost an international group of pressures trying to force the Chinese to join a value system that was being developed by the West.

And this went into many areas we think of as arcane: things like tariff structures, the way that China should be allowed to tax protected Western goods that were coming into China, the development of import and export markets, shifts in international currency, the shift between Chinese domestic interests in silver and a Western attempt to keep gold standards, a geographical expansion, the Japanese rise to power.

All of this extraordinarily complex mixture ended up with apparently ceaseless period of harassment of the Chinese polity. And it ended, I think, with an ambiguous situation. If you take Mao as a turning point, that would be the period in which there was a real closure of China and a declaration that enough was enough and that Western influence was to be barred from China while it tried to find its own revolutionary goals.

There was a kind of unity to that huge period. And it contains some amazing men and women who tried to change Chinese values.

It led to a situation in which Westerners who had hoped passionately to change China were deeply disappointed when the Chinese decided not to use their help. The result was a kind of embittered attitude toward China, a real anger with the Chinese for rejecting our values and a feeling that they were being stubborn and pigheaded about this. And it wasn’t just some natural cultural resistance. It was deeper.

So, much later on, I came to try and unravel some of these cultural attitudes in The Chan’s Great Continent, the book I did in the early nineties. It looked more at the whole range of ways that China itself had values to pass on to the West and how the West tried to interpret shifts in Chinese civilization. I’ve found this a grand theme, and I’ve explored it in different ways for more than forty years.

LEACH: In the nineteenth century, we followed the European spheres of influence approach. And in 1899, we announced the Open Door Policy.

SPENCE: Yes.

LEACH: And we Americans thought this policy set us apart from European powers. But I’m not so sure the Chinese looked at it that way. What’s your take?

SPENCE: I think the simple answer to a huge question would be that, from the Chinese perspective, the Americans were maybe more easygoing than, for instance, British or French or other colonial powers, but the Americans were interested in exploiting China just the same way that Europeans were.

They just had a different rhetoric and practice. The Open Door Policy on paper, at least, seemed more generous than the overt British expansionism into Chinese cities along the coastline or the French development of a power base in southwestern China. Then the Japanese developed a power base as well.

The United States was often on the periphery of these major movements until the 1930s or early 1940s. But Pearl Harbor changed this and brought American forces into China in a different kind of alliance.

I think in terms of studying negative foreign impact in China, the Chinese textbooks would refer to all these different aspects of foreign pressure, including the American, as being different kinds of imperialist pressure on the Chinese people and its government and its economy. Even though there have been conspicuous examples of Chinese enthusiasm for specific figures from the United States, there’s no huge legacy of pro-American feeling—for instance, note the Chinese feeling that American aid against Japan in World War II was not particularly necessary.

This is something very hard for Americans to take. And I can understand why, because huge sacrifices were made.

LEACH: In the twentieth century, China moved towards a communist model after it defeated the Kuomintang. Geostrategists like to compare the Chinese model of communism and the Soviet. Historians like to inquire whether or not the Chinese model of communism is compatible with Western democracy and with Chinese cultural history. What are your thoughts on either of those subjects?

SPENCE: There’s a lot to say about both. And it’s the stuff of much study of modern Chinese history.

I think the basic premise, though it’s not without opposition, is this: When the Soviet Union was in its revolutionary days from 1917 up to about 1921, when the Communist party in China was founded, it had a strong influence on the formation of the Chinese Communist party.

But already by the later 1920s, China had realized that conditions were enormously different than those of both the former Russia and the new Soviet Union. China’s role in world revolution was of a different nature: Internationalism in China could also be rural, and the workers could be rural, as opposed to the so-called urban proletariat or working industrial classes in the Soviet Union or in Europe or, on a much smaller scale, in the United States.

China was offering something quite different. It was essentially, we might say, the development of a Marxist-looking revolution, but on a basis of rural insurrectionary forces.

China would have the right to claim a different kind of revolutionary insight if it were to get the peasantry, which represented 80 or 90 percent of the Chinese people, and teach them about revolution and teach them their future could lie in their own hands under the leadership of the Communist party. Their exploitation did not have to be unending, foreign imperialism could be attacked and maybe gotten rid of, and a new kind of economic order could be established within China, in which the Soviet Union would be one of the members of a new kind of alliance, a left-tilted alliance.

This kind of interpretation is being chipped away at now, particularly because there is a general feeling that Mao has been given too much credit for the way that China’s revolutionary society tried to alter the nature of Marxist insurrection in the period from the anti-Japanese War through the civil war and then into the Korean War and out the other side into the Great Leap Forward.

All of this can be seen as showing a different Chinese view. How much did the Chinese Communists galvanize rural China into a truly revolutionary military force with immense potential power? How do we evaluate this and ask whether we’ve been partly manipulated historiographically by the Communist party of China itself into seeing this as the mainline filament? There is a return to a feeling that maybe a small, elite group of leaders in the Chinese Communist party were manipulating their own people and also manipulating the historiographical record to make themselves look good.

So, aspects of what we call post-Cold War or late Cold War study are still active and fruitful in our study of China. We have to remember that Mao died in 1976. There have been thirty-four years of post-Maoist rule and a lot of chance to reassess what exactly Chinese Communist doctrine was and how much foreign influence played in it. Or, was there a deep split in China itself between different branches of the left-leaning elite and military personnel? It’s a great topic for a historian.

It’s difficult to be precise because so many people were involved, and so many archives have not yet been cleared because they still have importance to Chinese politics today. And though early historical archives are beautifully organized in China and made accessible, Communist party archives are a different matter.

LEACH: I’ve often wondered how relevant the philosophy of Marxism was in how Lenin organized the government. The Leninist model survives, but Marxism doesn’t very much.

SPENCE: This was the stuff of decades of work by scholars of China. Marxism was selectively introduced into China and selectively used. There wasn’t even a complete Chinese translation of The Communist Manifesto until the early 1920s, when China was already beginning to form Marxist study groups.

There is an entire tradition of what we might call Utopian Marxism, a sort of culturally harmonious Marxism, seeing it as a way of analyzing class struggle and human suffering, giving power to certain analytical approaches. The Leninist system is more focused on the analysis of Communist party power and organization, and the role of the Communist party in fomenting revolution on the global level and of using China as a conduit to Japan so the Soviet Union could protect itself in its Eastern borders.

So we have a global influence, a domestic defense influence, and what we might call a social utopian kind of thrust. All of these, in different gradations, can be found in the way that Marxism made its way into China.

We run into all sorts of complicated problems: Some of the early Marxists were Buddhists, for instance. And we can find warlords who maybe were related more to Islamic forces in the new Western areas of China. One can find all kinds of different pressure points: Hong Kong, Manchuria, Tibet. All these areas have different challenges and organizational possibilities. And they have their own historiography in China.

“Leninist” can mean many things. To a rigorous Leninist scholar, much of Chinese communism would not be rigorously Leninist.

When I first went to China, I saw pictures of Marx and Engels. And Lenin and Stalin would always be displayed in Tian’anmen Square. And Mao was later added so that you have the idea of the “big five”: Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao. That was the deliberate Chinese patterning of the past so that Mao, with his domestic plans for China, could be seen as standing in a tradition of revolutionary growth that would take them from the Marxists, through the Leninists, into the Maoists’ view of the world.

LEACH: How did Deng Xiaoping change all this? And do you think he will prove to be a more seminal figure than Mao?

SPENCE: Deng Xiaoping certainly is going to be part of this story for as long as the story is told. From his earliest years, there are so many ways in which he is both typical and atypical. He was raised in a dispiriting period of China’s history: From 1910 to 1915 was a grim, miserable time.

Like many Chinese communists, Deng had gone to work in France at the end of World War I, where he was introduced to a more rigorous Marxist belief and organization.

When he came back to China, he became a tough-minded, disciplined young man of the Communist party and was involved in many of the great developments of the time. He was a military leader and a political commissar.

There was little in his past record that would lead one to expect the emergence of the Deng Xiaoping of 1978 onward, which is when he showed an extraordinary ability, I think, to work through what China would have to do if it was to become a post-Maoist power, while still maintaining the organizational toughness of the Leninist party structure.

So what on earth was one to do about galvanizing this economy when you have such a huge structure of state-controlled enterprises in the industrial sector, when you have such rigorous supervision over farm production in the huge hinterland of China?

He had senior Communist colleagues who agreed that China somehow had to break out of what had become a rather fragmentizing legacy from early Marxism. How could one take some of the patterns of capitalist development, some of the expansionist goals? How could one follow some of the technological successes of Taiwan, for instance?

How could one look at the financial innovation shown by Hong Kong? How was one to draw all this into a synthesis and somehow keep the same leaders in power? That was an amazing thing to do.

I think we’ll remember it was amazing, even if we start listing other people who helped him do it and find intellectuals who were whispering into his ear about the best way to go.

Deng was not particularly forthcoming, so we don’t know that much about him biographically. We can see that he had an extraordinary determination to push China away from the Leninist/Marxist direction into a kind of global economic position. Though, again, there was no way one could have anticipated the kind of accumulation of foreign reserves that China has achieved. I don’t think we could ever have guessed that from Deng Xiaoping.

LEACH: One has the sense that for much of the twentieth century, the great borrowings from the West were Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin. With Deng Xiaoping, the borrowings became maybe Henry Ford and Andrew Mellon.

SPENCE: Who is controlling Deng Xiaoping, do we know? Who is making a report card on him? It was just a terrific amount of bold thinking and shrewd experiments in the area of Guangdong and also in Sichuan. These were used as trendsetters.

Then there was the whole idea of trying to open up landholding, so there’d be more use of private markets, more incentives to carefully start closing some of the least productive industrial facilities and factories. All this meant the possibility of alternative employment, the avoidance of domestic insurrection.

It’s this same Deng Xiaoping who is opening up the country in 1978 and 1979 and who is ordering the troops into Beijing in 1989. This is the same person making this decision that is harsh and antidemocratic and yet linking China to something that is much more open and flexible and creative.

Humans are paradoxes, and Deng is a good example of a paradox in action.

LEACH: Well, in thinking through these centuries that you have studied, would you say we have borrowed much from China?

SPENCE: We’ve borrowed much from China. I’ve been thinking about this because of the Jefferson Lecture that I’ve been asked to give. I’m trying to work out times in which the cultures were more parallel or more different. ‘Who learned from China and when?’ is, again, one of these colossal historical questions.

This reaches back into Marco Polo’s day. Not too long after the initial contacts with China, the West learned that China was a huge country with a complex professional bureaucracy and a strong centralized government.

There’s a huge variety of early writings on China. Visitors were fairly awestruck by China’s power and extent. They couldn’t help wondering if the Chinese didn’t have some principles of organization, for instance, like the examination system and the bureaucracy or certain aspects of effective tax gathering or military garrison preparedness. It was also a terrific country for engineers, who made major hydraulic and irrigation works.

A flood of books about China began around about the 1590s into the 1600s. Some were written by Jesuits. Some were written by diplomats. Some were written by part-time travelers, armchair travelers, some by people who were able to read Chinese a little bit. And they saw a lot to admire.

LEACH: A few years ago I read about a nineteenth-century Chinese trade model that influenced American banking. The idea came from Canton, where merchants had reinsured each other. In essence, they took mutual responsibility for losses. The New York state legislature passed a law allowing mutual insurance into commercial banking. The model was copied at the national level and became the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

SPENCE: That’s fascinating, and perhaps the model grew from the Cohong system where a small group of Chinese merchants were given permission by the state to do international trade. The Cohong merchants certainly supported each other through mutual loans and by pooling their resources. They were able to develop enormous wealth, but they were also subject to incursions by the state, which regularly raided their profits. Western firepower ultimately destroyed that system in 1842 in the so-called Treaty of Nanking.

LEACH: What had changed the admiring attitude toward China?

SPENCE: As China weakened geographically and militarily under onslaughts from a technologically advanced West somewhere around the 1840s, China began to feel threatened, but tried to avoid it by pretending it wasn’t happening. And that’s usually a disastrous thing to do in foreign policy.

By the 1840s, China was seen as a has-been power, and the earlier praise for administrative skill became contempt for imperial bigotry. And the exam system became known for mindless rote learning, which held back most of the population. And the peaceful countryside world was seen as one in which the peasants were kept down by force.

So there’s a sliding scale of what Westerners thought they could learn from China. I think now we’re desperately torn.

We’re not sure what we should be interested in about China. We’re not sure how China can balance its own initiatives against the real crises that it faces: the crises of water and pollution, disorder and protests against the pace of urban development, the difficulty of an automobile society, and the mobility brought by new domestic airlines. China just has so much going on—it’s awesome.

How much of this can we learn from? Some of it we’ve done already. Some of it we’re trying to do. Some of it, like magnetic resonance trains and this kind of thing, we’re finding, is very expensive. So, we’re realizing that we’ve got to struggle to keep up technologically.

But when I taught about China—I was lucky to have a good many years to do that—I always began in the seventeenth century as China drew itself together with a new dynasty, the Qing. I wanted students to start with a clear idea of an extremely tough, well-orchestrated, well-organized China that had come through a difficult civil war and foreign invasion and then developed extremely good leadership, even though it wasn’t democratically chosen.

The late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century emperors had a strong sense of government and a pretty good sense of leadership responsibility. They were shrewd analytically. They had a good overall sense of finance. They worked extremely hard, twelve-hour days, fifteen-hour days. They read an immense amount of documentation on the country at large.

They also were tough as anything and willing to make decisions that we regard as ruthless. My main teaching premise, though, was ‘Let’s start with a strong, outward-looking China that’s also expansionist.’ It’s a period in which China doubles its extent within eighty or ninety years, a period in which China incorporated Taiwan. It sent forces into Tibet.

It conquered much of the Far West, thus giving itself a large Muslim population. There was its own domination within Manchuria, the settlement of the borders with Russia, and the containment of Western, particularly British, French, and other European states’ trade in China. If you come to China from that perspective, the less like the nineteenth century it seems.

The weak period seems more of an aberration. And China in the last twenty-five years or so seems to have been back on that earlier track: tough, pragmatic or sometimes ruthless, sometimes determined to strengthen its hold over its border areas, very watchful about any kind of mass demonstration, extremely watchful about written words that could be critical of the government, extremely cautious about crowds assembling in any way.

Not to give a sort of déjà vu sense, but we’ve been to some of these places before. Let’s not just worry about everything now being so huge. I guess the historian is trying to say, ‘No, it’s not exactly new.’ It hasn’t all been done before, but the broad premise is one we can recognize.

LEACH: Let me just ask you about the geopolitical contrast between the United States and China involving the island of Taiwan. Many people believe this is the one rub in our relations. How do you see this being resolved?

SPENCE: Well, if I knew that, I would be a sage. It’s extraordinarily difficult. We can see when Taiwan began to develop some ties with China through trade in the seventeenth century. We can see how the Dutch tried to make it a base for their empire in the 1620s. We can see how it was slowly incorporated into the Chinese governmental structure after the 1680s, as part of the Qing dynasty’s expansion.

What makes Taiwan so complicated is that it was essentially made over to Japan by the legitimate Qing government in the 1895 treaty settlement after Japan’s victory over China. Taiwan was lost to China and became a colony of the Japanese. And it remained in that colonial status until 1945 with the surrender of Japan.

Then, with startling speed, before it had really developed any of its own potential on its own terms, Taiwan became the staging area for Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist regime. So Taiwan then became a kind of counterrevolutionary bastion.

Because of the politics involved and the loyalty many people felt to Chiang Kai-shek and the hostility that others felt to Mao and the Communists, Taiwan became the recipient of significant amounts of American aid. Slowly it began to modernize and then develop with remarkable speed once it had undertaken successful land reform.

It became a democratic government in the nineteen nineties and then solidified that with an uneasy, but nevertheless working, balance of forces in the election pattern, between different generations of Taiwanese settlers and the earlier Taiwanese themselves, through links to indigenous populations and links to Japan through some of the educated elites. In terms of international law, this is really a unique situation. People are not meant to ever say that in history.

But it’s amazingly unusual. And exactly what the pros and cons are depends on how long you think a country has to control parts of a border area for that area to be totally integrated into a major player. In this case, what are the economic and political rights the mainland may have to Taiwan?

We have watched this difficult tension. We’ve had the Taiwanese regime under Chen Shui-bian. We’ve had the more Japanese-educated and American-educated regime of Lee Teng-hui before that, and Chiank Kai-shek’s son before that. We have the prosperity of the country itself.

There’s an awful lot going for Taiwan as a domain in its own right. And that’s what we have to try and juggle. So I can’t think of a much harder problem globally. There may be bigger problems in some ways, but this one has so many aspects that, I think, holding on in the way that people are doing so, at the moment, seems to be the most hopeful way.

LEACH: I’d like to end with one final query. Do you think there are fundamental Chinese ideals that Westerners misunderstand?

SPENCE: It’s a crucial question. It’s just very hard to answer. In terms of philosophy and organizational skills and development of moral argument and ideas about governance, China has a rich tradition whether one has any interest in modern China or not.

The research in China now into the roots of its own civilization is intense, and it’s being done by some incredibly good scholars, both of the senior generation going right back to the forties and fifties down to kids in college who are drawn to the fifth- to third-century period of Chinese thinking. That’s BC.

This period shows us Chinese people—intellectuals, writers, poets, and administrators—thinking through the meaning of administrative work, thinking through the nature of rulership, thinking through social problems, looking at education in a deep and complex way, philosophically thinking about the family, thinking about different possibilities for what was often a wartorn and fragmented group of smaller states. There were a great many countries that could claim Chinese values.

Within this body of scholars now there is a fundamental belief in the richness of their own tradition, which gives them a real nationalist pride. And I think that’s justified. This is such a fine scholarly tradition. It is also such a witty one with its Taoist side. It’s a potentially compassionate one with some of its Confucian values.

The state itself is interested in China being perceived as a culturally rich and enriching place.

So the attention given to archaeology in China is one of the fascinating sides that Westerners outside academia don’t know much about. But China is just the busiest place in terms of restructuring the past, recapitulating all of its previous achievements.

It’s just the most ebullient area and a particularly exciting one. We should ourselves, I think, be willing to study the Chinese past along with Chinese scholars.

That seems to be what a lot of our students are getting into as their language gets better. They can work with younger Chinese and begin an exploration of this earlier stage of global civilization that will be maybe helpful or reassuring to both nations.

LEACH: Thank you, sir.

SPENCE: Thank you for your shrewd questions.