“I like the idea of history as jazz,” says the voice, young, female, and smooth. “You’ve got the main groove, but also these in-between notes that make the song memorable.” This is not your normal historic walking tour. My guide, Alexandra McDougall, speaks with a casual, almost seductive, intimacy. And she’s right in my ear, coming through earbuds connected to my iPhone.

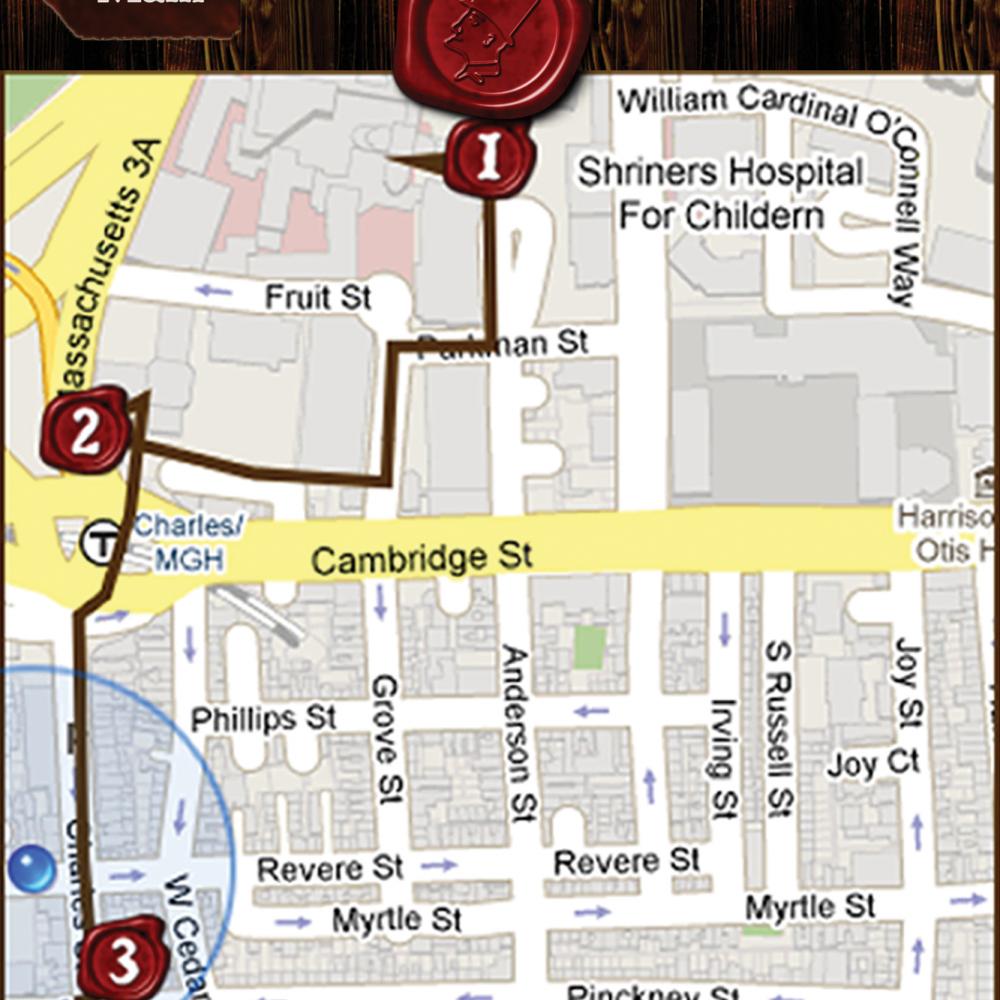

For the next couple of hours, I’m going to personally explore a famous 1849 murder that took place in the old brick-townhouse neighborhood of Boston’s Beacon Hill. I’ll see clues and evidence, the site of the evil deed, and tread the same narrow streets that the murderer and his victim did. My tour guide, the hip Alexandra, along with a self-paced program of dozens of brief geocoded videos, will walk me sequentially to eight sites—about a mile of foot travel—that illuminate the murder. The wealth of historical material could hardly be more portable—it all plays out on my iPhone, an inexpensively downloaded app from Untravel Media called Walking Cinema: Murder on Beacon Hill. But in contrast to the classic posture of a handheld-device user—elbow crooked, face peering downward at the tiny screen in one’s palm—this is “heads up” media: screen technology that makes you look up and out at your immediate surroundings.

In its time, the Parkman murder had worldwide notoriety, largely because both murderer and victim belonged to Boston’s privileged class. It was probably the most famous American trial of the nineteenth century, the era’s equivalent of the O. J. Simpson case. The upscale homicide seized the public’s imagination in a Boston before there were Red Sox or Celtics or Kennedys. But not before Harvard: The victim, Dr. George Parkman, and the perpetrator, Professor John Webster, were Harvard classmates and doctors. When such a prominent citizen as Parkman, son of the richest man in the city, went missing, a massive manhunt ensued, with a grisly conclusion. Parkman’s dismembered body parts were discovered beneath a lab that belonged to Webster, who was arrested, jailed, tried, and hanged the following year.

Historian Simon Schama, while a Harvard professor, told the lurid story in his 1991 book,Dead Certainties, which PBS later used to develop the documentary film Murder at Harvard, whose director, Eric Stange, coproduced Walking Cinema. Supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Center for Independent Documentary, the iPhone tour is a first-of-its-kind, location-based adaptation of a significant documentary, which uses clips from the film interspersed with original footage. The multimedia package offers an involving experience for a vacationing tourist, or even a local like me. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. It’s a museum wand on steroids.

The tour starts at an old granite building, part of the compound of one of the world’s most distinguished medical facilities, Massachusetts General Hospital, or MGH. (In his 1978 medical black comedy, The House of God, Samuel Shem styled MGH “Man’s Greatest Hospital.”) Encouraged by Alexandra, I climb stairs to the Ether Dome, where the advent of anesthesia stunned the world in 1846. Once back outside, I’m not far from the site of a hospital building that contained Professor Webster’s office; the gruesome remains of Parkman were discovered in the mudflat below it. The video’s Ken Burns-like sepia photographs depict the building, which “is gone, but not all of it. Some still remains,” Alexandra tells me, “very close to where you’re standing now.”

She gives me detailed directions to a square stone pit, about fifty yards away, with a ladder going down it; the video pans around the area and shows landmarks as she, in my ear, takes note of them: a café with tables, a tall building, a stone sculpture of a mother and infant. It is a new, uncanny, and almost thrilling sensation to see something on the handheld screen that exactly reflects my immediate surroundings. Alexandra describes the sculpture, the video shows the sculpture, and there it is!—eight feet to my right. It’s an experience that I’ll repeat several times as the tour unfolds.

When I reach the wrought-iron railing around the stone pit, the video soundtrack clinks repeatedly, the sound of a hammer and chisel chipping away at stone. Meanwhile, the cinematography uses the camera angles and pacing of suspense movies (think of Alfred Hitchcock’s way of creeping up to a precipice, then suddenly looking over the edge). Together with a dark, anxiety-provoking musical score, they set the murder-mystery mood.

Alexandra tells me that a janitor, motivated by the $3,000 reward offered after Parkman disappeared, spent three days chiseling away at the underground stone wall of Professor Webster’s private vault below his office. When he finally broke through, the first thing he saw was a human pelvis and two parts of a leg. As I peer down over the railing, it suddenly hits me that I am gazing at the very place where, a century and a half ago, that clinking sound went silent and the janitor no doubt gasped at this macabre discovery, and a chill goes through me. The murder story, whether told via book, film, or handheld video, is unsettling, but when your narrator has taken your hand and tiptoed into the details with you, seeing the actual venue makes you feel like a witness to the crime.

The app, Walking Cinema: Murder on Beacon Hill, is available for download at www.parkmanmurder.com, where its video and audio are also accessible, free of charge. A forty-three-minute movie combining all sixty-three mini-videos of the tour screened this April at the Boston International Film Festival, where it won the Indie Spec New Media Award. The app and tour are a product of Untravel Media, a company launched in 2006 by Michael Epstein, a young MIT graduate who majored not in engineering but comparative media studies. “I had a strong feeling that these mobile devices could offer highly produced, cinematic stories that give you a different kind of experience,” he says. “Mobile media can put you in touch with places and people. You find all these storytelling techniques coming together in this platform.”

As the videos progress, a television set (with Alexandra watching) appears in different outdoor locations as clips from Murder at Harvard show actors playing Parkman, Webster, and, yes, the entrepreneurial janitor. Several onscreen comments from S. Parkman Shaw, a living descendant of George Parkman, connect the story with the present day. The eight story-sites appear on the overview map as red-wax seals, emblems of upper-class correspondence of the era. Navigating your way to them is easy. The iPhone receives a live GPS feed that places you precisely and shows your current location as a blue dot on the iPhone’s maps of the area—so even when you’re lost, you aren’t. But I chose to rely less on the maps than the audio alternative: Alexandra giving me explicit directions from place to place. I guess I just like the sound of her voice.

There are surprises you wouldn’t encounter on an ordinary tour or art-museum audio program. The second site, for example, is a large stone building that operated for more than a century as the Charles Street Jail but has recently been privatized and reborn as a luxury hotel—renamed, somewhat ironically, the Liberty Hotel. In the hotel’s mezzanine lobby, encouraged by Alexandra, I ask the concierge for “the Parkman Game,” which turns out to be a wooden reproduction of The Checkered Game of Life, a nineteenth-century version of the twentieth-century Milton Bradley game Life. The squares of the 1860s game depict Honor, Shame, Crime, and other human fates, all with clear moral subtexts. (There’s even a Suicide square; those landing there are instructed to remove their piece from the board.) Studying the game board gave me a concrete way of taking in the bracingly clear moral certainties of the mid nineteenth century, a useful backdrop to understanding not only the reaction to the Parkman murder but the far more ambiguous moral climate of our own time.

Along the tour’s path, the producers have made analogous arrangements with the businesses and organizations that are among story sites. At a small shop called Black Ink, I view their selection of dozens of old wooden stamps—the kind used with an inkpad. Mingled in surreptitiously with the ones for sale are a few others, planted just for those on the Walking Cinema tour; these reproduce drawings from contemporary newspaper accounts that show, for example, how the image of Webster evolved from a genteel doctor to a progressively more sinister character, a real-life version of Jekyll morphing into Hyde. Later, I gaze at Parkman’s actual house at 8 Walnut Street on Beacon Hill, an impressive brick pile he built two centuries ago, which still impresses today in a neighborhood whose homes sell in the seven-figure range. Alexandra invites me to look at the upper-story windows and imagine Parkman planning his meeting with Webster, where he would confront the professor about his delinquency on a debt to Parkman that would amount to around $200,000 in today’s money. It proved a fatal debt-collection strategy, as Webster chose to eliminate the creditor rather than the obligation.

The tour winds up at the headquarters of the venerable Appalachian Mountain Club, the outdoor- and conservation-oriented organization founded in 1876 by Boston Brahmins, people of Parkman and Webster’s social class who were looking to escape from the growing city to rural retreats where they could hike and enjoy lavish picnics. Pausing before the club’s front door, I follow Alexandra’s instruction to turn around and look up to view the golden pinecone atop the State House; she says the pinecone is there to symbolize the forests that provided wood to build the city. It turns out that I’m just a few minutes too late to go inside the club, though, which is open only from nine to five on weekdays. Thankfully, the videos on my iPhone that correspond with the last stop teach me how the natural world, too, played a role in the case.

It turns out that Webster, a chemistry professor, was also a geology enthusiast who owned a valuable rock collection of minerals he had acquired in his travels. He put this collection up as collateral for the loans that Parkman extended to him. However, Parkman one day learned that Webster had also used the rocks as collateral against another loan that he took from Parkman’s brother-in-law. It’s easy to imagine how poorly this went down with Parkman, and how eager he was to set Webster straight about his double-dealing. The conflict between the two men “actually started with rocks,” Alexandra tells me, “which became a mountain between them.”

Inside the club, there is a logbook that details several of the quasi-scientific follies Webster carried out during his life; one, for example, is called the “mastodon debacle,” in which he convinced sponsors to purchase for Harvard a mastodon specimen recently discovered in New Jersey. The mastodon was real, but the entire sum did not materialize and Webster had to call on Parkman again to make up the difference. There are chairs inside where one can sit and explore some of Webster’s stranger notions; to do that, I will have to come earlier in the day. For now, I’ll set out for home with a better grasp of the nineteenth century, a haunting story to muse upon, and a new kind of tour to share with my friends.