Early in his naval career, the French medical officer Victor Segalen happened upon the beachside abode of artist Paul Gauguin. The year was 1903 and the rebellious painter had succumbed to the effects of syphilis three months earlier. As Segalen approached the hut on the far-flung island of Hiva-Hoa in French Polynesia, he came upon Gauguin’s servant, Tioka: “There is no more man now,” the servant said, referring to Gauguin.

Segalen was a writer, and he later recorded the experience, calling the scene sumptuous and funereal, splendid and sad, and a little paradoxical. At the time, he knew nothing of Gauguin or his work, but the near encounter seemed fated. The two Frenchmen had much in common: a sense of mystery, a fascination with the primitive and the exotic, and a gift for ambiguity. From 1903 until his death in 1919, Segalen’s poetry and prose would, like Gauguin’s art, try to discover the exotic on its own terms while increasingly confronting the limits of the Western artist’s own powers of apprehension.

Segalen’s greatest feat was breaking with the colonial exoticism of such nineteenth-century writer-travelers as Pierre Loti and Rudyard Kipling. Where those authors made no pretence about surrendering Western, or even imperial, values while depicting foreign cultures, Segalen was intensely self-conscious about his depictions of the other in ways that seem especially modern. If Kipling was the confident Westerner in his perceptions and art, then the intrepid Segalen bravely sought to move beyond his own viewpoint, but without any confidence in the powers of man to see and understand all that he surveys.

Writing about the primitive and the exotic should rely, thought Segalen, on an awareness of the shifts the self undergoes when confronting the truly foreign. Developing an aesthetic of difference, he came to realize, requires practice and training but, once developed, can yield ecstatic moments of discovery.

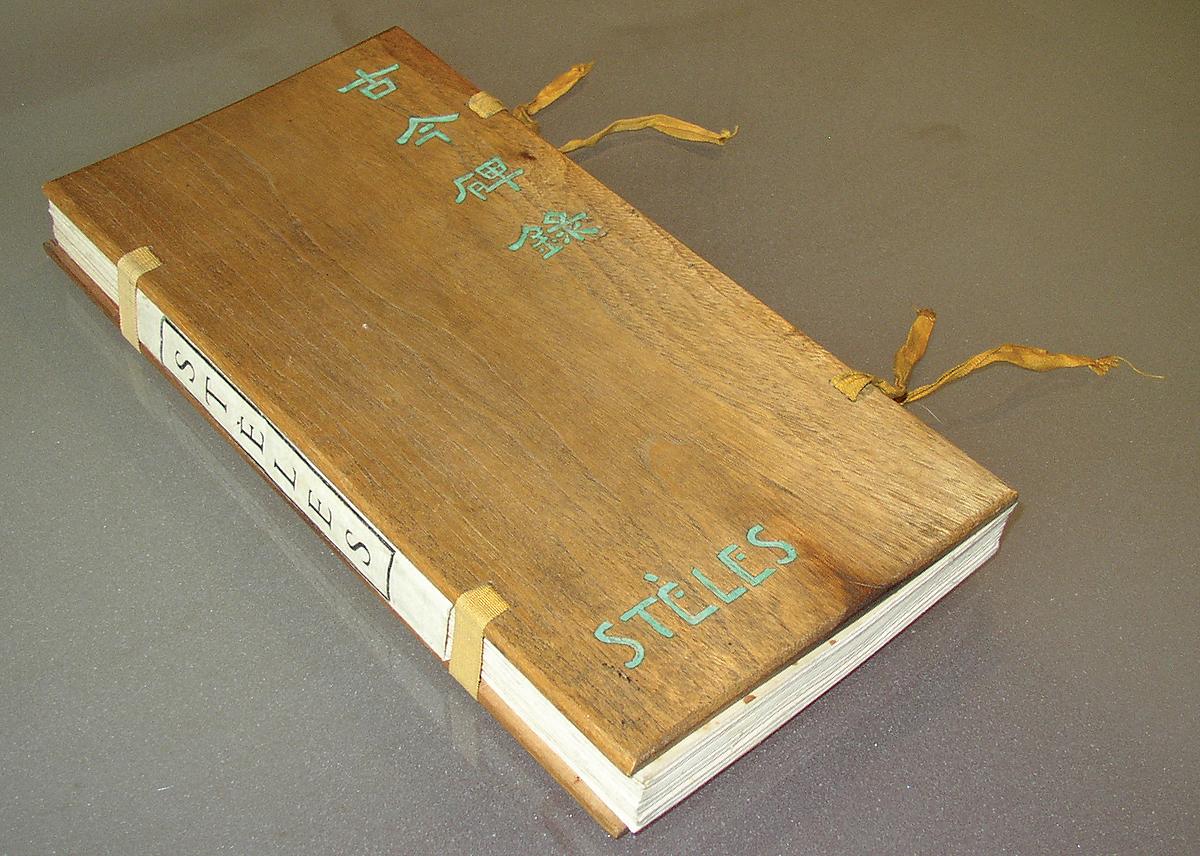

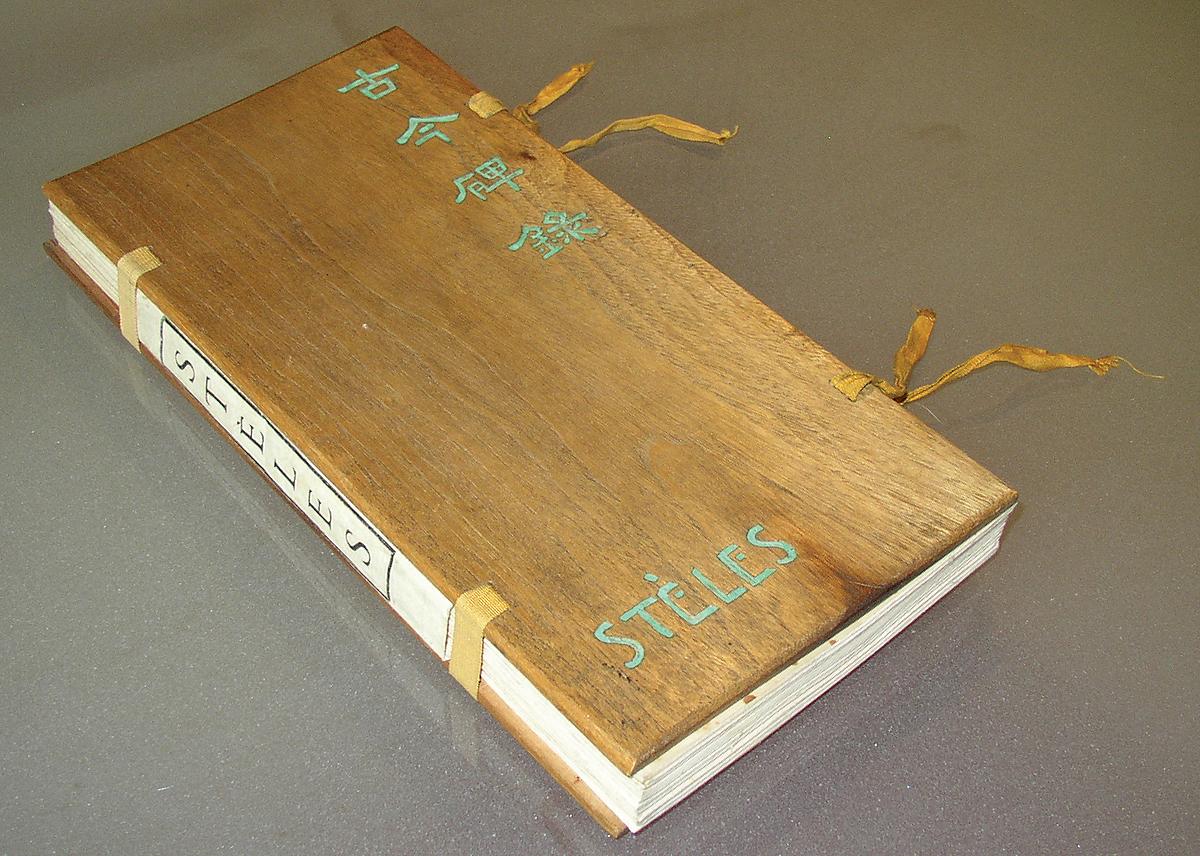

The collection of prose poems, Stèles, along with a thriller set in Peking, René Leys, are generally regarded as his masterpieces. But Segalen wrote other novels, as well as travelogs, collections of poetry, essays, plays, and much correspondence. Taken together, his work is now understood to be among the more significant expressions of an early modern sensibility.

Segalen was, indeed, on the same artistic wavelength as Gauguin. Shortly after his arrival in the South Seas, the painter realized that the missionaries who had preceded him to French Polynesia in the first half of the nineteenth century had destroyed most of the culture’s sacred objects. These were the very objects Gauguin had hoped to find and incorporate into his paintings as a way of understanding the Maori culture.

A novel Segalen began writing a month after arriving in Tahiti, Les Immémoriaux (translated into English as A Lapse of Memory), is told from the point of view of a Cook Island Maori named Terii who sailed for decades with Europeans soon after the time of Cook. Previously, Paofaï, known as the last master of pleasures, set out with Terii to find a way of writing that would fix words in place, keeping them from dying. Upon his return, Terii betrays his former teacher, abandoning the language and legends that defined his culture. In this novel, Segalen adopts a Maori point of view to comment on Western culture, an audacious and ironic act.

Several of the poems in Stèles go beyond culture to address the exotic in nature and elsewhere. Segalen believed the decline of class distinctions the world over was contributing to an increasing sameness. His thoughts on politics can seem as retrograde as his thoughts on culture seem progressive. Democracy, he complained, was the gateway to a “Lukewarm Kingdom.” And his exoticism would have found little joy in a feminism that dissolves boundaries between the sexes; for Segalen, as scholar Yvonne Hsieh, has said, “the distance between a man and a woman is a primary source of aesthetic pleasure.”

It would be an oversimplification, though, of Segalen’s theories of art to see his early work as merely opposed to the grinding uniformity of the day. Diversity, obliterated in one place, he felt, soon manifested itself somewhere else.

His aesthetics, like Gauguin’s, were often too esoteric for his contemporaries and not always in sync with those of the generations that followed. It would be several decades after his mysterious death in a forest in Brittany before his literary and aesthetic accomplishments would be fully appreciated.

By 1905, Segalen was back in France, where he finished Les Immémoriaux. He studied Chinese for a year, then passed an examination that enabled him to continue his studies in Peking. There he became fascinated with the Imperial City and the intrigue at court, which he learned about from a young Frenchman living in Peking named Maurice Roy, who was fluent in Mandarin Chinese.

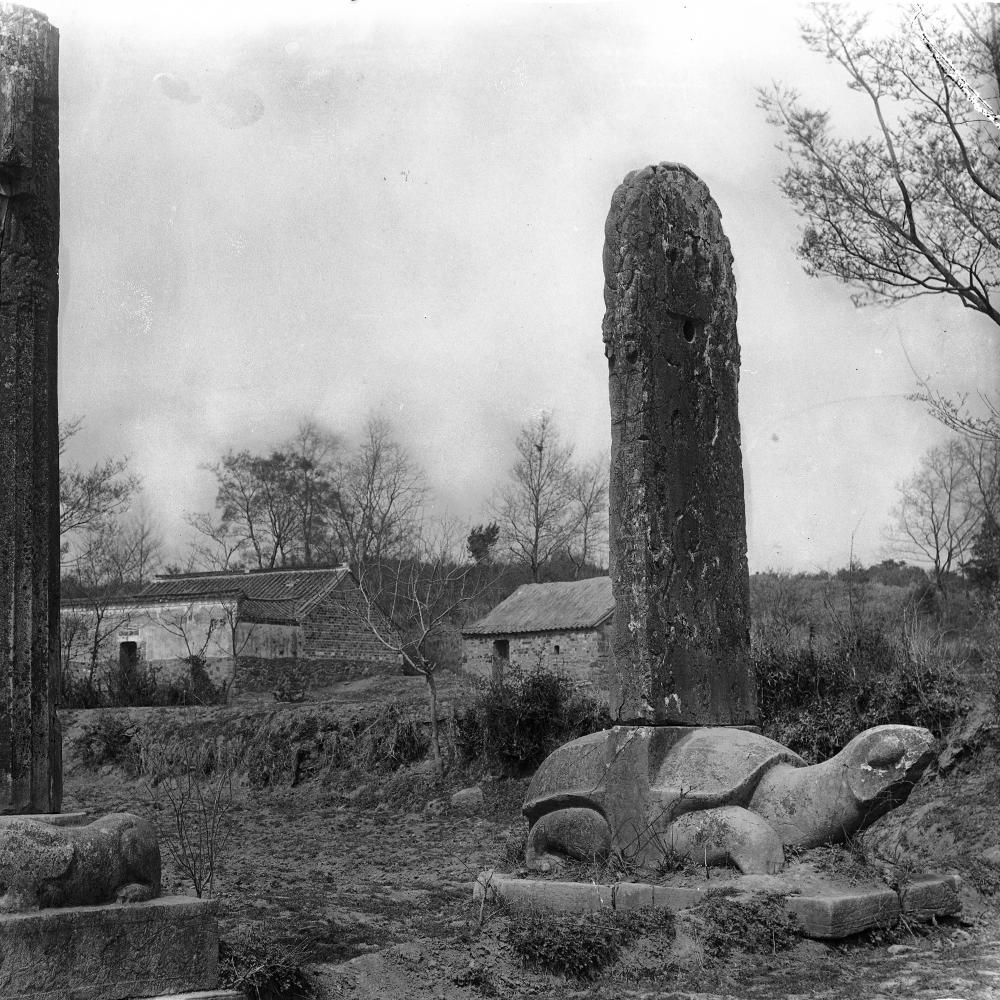

Segalen’s literary reputation was made both by the novel he set in Peking during the tumultuous months leading up to the abdication of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, and by the prose poems he collected in the interlingual and enigmatic tome Stèles. The poems brief, allusive, and elliptical—emulate the hieratic inscriptions on stone tablets Segalen came across during archaeological expeditions in central China. Like other examples of found text they read as if written for a different purpose. He summed up the impact of the steles he came across in his travels: “They do not express; they signify; they are.”

Both René Leys and Stèles refine Segalen’s concept of the exotic. René Leys achieves this by placing Victor Segalen himself at the center of something called The Book That Never Was as a diarist who maintains his French identity and artistic sensibility even while immersing himself in Chinese language and culture. The narrator coaxes inside information about the goings-on at court from knowledgeable sources. The seventeen-year-old wunderkind René Leys, fluent in Mandarin, through Scheherazade-like tales of the pleasures and dangers of court life, keeps Segalen in a near-constant state of exotic rapture.

In those days, Peking housed foreigners within the Legation quarter on the southern boundary of Tatar or Manchu City. This was where Victor Segalen had a large, comfortable house. Not far from the Legation quarter in distance, but light-years away in every other respect, was the walled Imperial City and within that, further immured, the Forbidden City.

The action of the story shifts as the narrator races a horse along the ramparts of the Imperial City at night, attends the incomprehensible, raucous Chinese theater, and plumbs the experiences of Leys at court. But the tension always derives from the seesaw of perception between uncomprehending awe and fleeting instances of recognition. Segalen learns of young Leys’s amorous adventures at court, and that Leys was only able to pass into the Forbidden City by wearing the costume of a Manchu princess. The question for Segalen then becomes, “Can a normal, nubile European love a Chinese woman, or more exactly a Manchu woman? And above all, can he be ‘loved’ by her?” René Leys thereby rises above what Segalen referred to dismissively as a “documentary book.” What might have been a limited firsthand report becomes a fictionally transformative account that reimagines China.

Beguilingly ambiguous and stubbornly protective of its secrets, René Leys must remain, however, The Book That Never Was because the narrator and author both tell a tale limited by its point of view. A story told in the omniscient third person would have had a much greater chance of commercial success, but, in Segalen’s view, would not have rung true. The story is also without plot or resolution. René Leys is found dead, and without the young polyglot at court to serve as the narrator’s eyes and ears, the enticing details of the Manchu empire’s final days, which could make for a bestselling page-turner, are out of reach. The exotic, then, in René Leys and elsewhere in Segalen’s work, is never fully recognized or described by the traveler-writer. The exotic lies, as it must, outside the self.

Stèles, published between 1912 and 1914, is the truest embodiment of Segalen’s aesthetic principles. These short poems emulate Chinese inscriptions on stone tablets placed at tomb sites. They often consist of Chinese writings that are then translated and recreated by Segalen as prose poems and accompanied by Chinese epigraphs. The voice behind Segalen’s stèles is that of a Chinese literatus, who can address the reader on a variety of themes, including chivalry, friendship, and virtue. All of the poems are, however, subject to sudden insertions of decidedly Gallic irony.

In “Chivalry,” a victor in a match states what is decorous behavior toward the vanquished. The winner promises to be ceremonious and to present the loser with the “honorific cup.” The final two stanzas, though, take a most unchivalrous turn.

But, filling the horn with warm wine—as he drinks—I will pour, in the bottomless well of my soul,

All the sweet torrents of a decorously ceremonious laughter.

Translators Timothy Billings and Christopher Bush suggest the poem may have its origins in a New Year’s banquet Segalen attended with Chinese friends. Drinking games must have been the order of the day, which Segalen would transform while speaking from behind a Chinese mask with a French accent.

In “Abyss,” Segalen takes an introspective turn. Two stanzas about a man, possibly hopeless, are followed by two stanzas in which another, the speaker, awakens with a “shiver.” He no longer wants “to see only night.” American poet and translator Paul Auster has noticed that there is more to Segalen’s poetry than the literary exoticism he is best known for: “By freeing himself from the limitations of his own culture, by circumventing his own historical moment, Segalen was able to explore a much wider territory—to discover, in some sense, that part of himself that was a poet.”

His taste for the gothic is explored in the somewhat odd, yet intriguing poem, “Vampire.” It emulates a tomb-site stele with its origins in Li Chi (the Book of Rites). “Vampire” enunciates proper treatment of the dead. They are not to be treated as “equivocal beings.” The deceased are gone from this world: “To treat the dead as living, what a want of discretion!” But ultimately the departed is bid to gorge himself “on the hot liquor” of the speaker’s heart.

Another stèle, “To the One,” is less ghoulish and more traditional. Originating in Confucian precepts on human relationships, it acknowledges the devotion reserved for the prince, the love reserved for a wife, the affection reserved for a parent. “To the one like a cavern who resounds with my baying,” however, the speaker says, “I offer my singular life: only my life is mine.”

The forthrightness and lyrical appeal of many of the stèles notwithstanding, it was not until after World War II that critics began to see Segalen more favorably. Till then, Segalen had been regarded as a minor figure toiling in the narrow discipline reserved for literary works penned by doctors abroad on mission. But soon, his reputation began to soar, first in France, then internationally, with the 1955 edition of Stèles.

At about the same time the likes of French ethnologist and poet Michel Leiris and the pioneering anthropologist and structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss recognized in Segalen’s writings a radical exoticism with concerns that preceded their own work. Segalen’s imagined travelog Equipée, Leiris’s Afrique fantôme (Phantom Africa), and Lévi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques (sometimes translated as A World on the Wane), critic Charles Forsdick said, “all reveal a deep suspicion of ‘objective’ ethnographic travel accounts and a recognition that approaching the other is both (culturally and personally) revelatory of the self.”

The self was, in fact, what Segalen thought he was about to come back to in Brittany in 1919 after a brief stint at the front and years in which he had begun to see himself as a perpetual traveler. But for a while he had been sick and complaining vaguely about his health. While out hiking alone in the rough terrain of Brittany’s Huelgoat forest he apparently fell and severely wounded his ankle. He lay there for two days, the story goes, and died from exposure to the elements. His body was found with an edition of the complete works of Shakespeare opened to Hamlet at its side, which has prompted some to see his death as suicide. His own life, then, ended as much of his work did, in mystery and ambiguity.