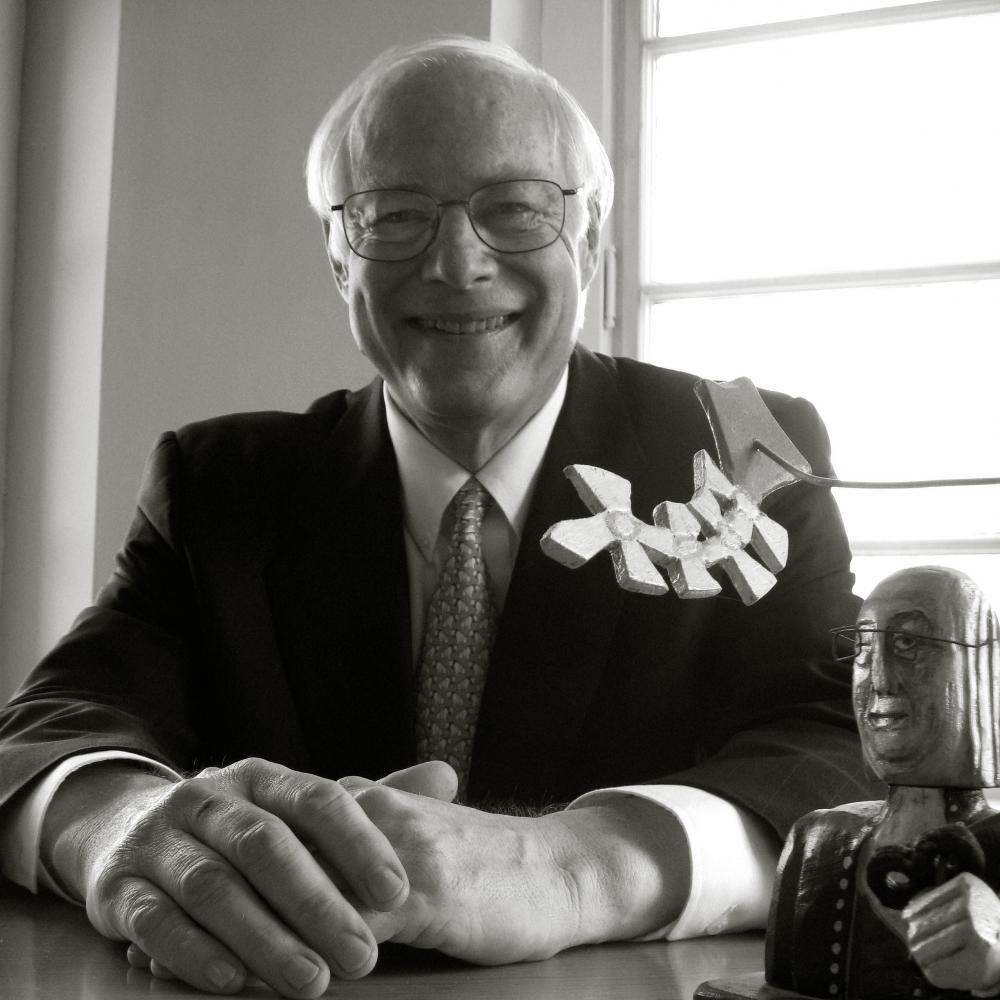

After thirty years of service in Congress, James A. Leach has been appointed by President Obama to head the National Endowment for the Humanities. In this interview he takes us from his high-school wrestling days through the stages of his political career to his thoughts on the challenges facing humanity—and the humanities—in the twenty-first century.

HUMANITIES: Before exploring Jim Leach, the politician and intellectual, let’s talk about Jim Leach the athlete. You wrestled in high school, college, and even while you were in grad school. But tell us what feats of strength earned you admission to the Wrestling Hall of Fame.

LEACH: Contrary to public imagery, wrestling is not weight lifting. The art of wrestling is manipulating not only one’s own strength but one’s opponents’. At key moments a wrestler moves with his opponent rather than pressing force directly against him. There are, of course, aspects of wrestling that are not like that, but one learns through repetition and instinct to use an opponent’s momentum against him. Strength does matter, but it isn’t the principal gauge of who is likely to prevail.

HUMANITIES: So a wily wrestler has a chance of beating a stronger wrestler.

LEACH: Yes, in fact, I’ve always thought that the most equalitarian place in the world is the wrestling mat. You have two people operating with the same goal in mind and abiding by the same rules. Wrestlers may differ in height and body type, but it’s hard to say who has the natural advantage. A taller, lankier wrestler has leverage advantages over a shorter, squarer wrestler. But shorter, squarer wrestlers often have springier power. People match up in very different ways. Wrestler A may defeat wrestler B, and B may defeat C, but that doesn’t mean C can’t beat A.

HUMANITIES: What was your wrestling weight?

LEACH: I wrestled in high school at 138 pounds, and in college at 147 pounds and 157 pounds.

HUMANITIES: You competed in other sports as well?

LEACH: I captained the “sprint” football team at Princeton (seven schools have teams on the East Coast) and played rugby both in college and in graduate school in Britain. I also joined the premier wrestling club in Britain, where wrestling is for those who don’t go on to college or even far in what we call high school. Participation-wise, it’s more like boxing in the United States. At least in London, wrestling has a lot of Cockney enthusiasts.

HUMANITIES: Tell me about your parents and how family life shaped you.

LEACH: Well, I had a very close family. My parents were very unusual and quite wonderful. My father was quiet, almost shy, academically oriented. He graduated from the University of Iowa and then studied at Stanford and Iowa law schools before going into private practice for a few years in the early 1930s. Law didn’t really suit him. He didn’t have a sufficiently confrontational disposition, though ironically he ended up leading one of the several most casualty-inflicted regiments in the greatest confrontation in history, World War II. After the war, he returned to Iowa to build on a series of small businesses he started during the Depression.

My mother was a natural leader, the best-read person I ever encountered. She read four to five books a day. People would come over, and she’d be reading as she carried on conversations. It would look like she was just thumbing the pages, but she was simply the fastest reader anyone ever met.

Our home was warm and loving, the center of neighborhood activity. I had one sibling, an older brother, whom I much admired. He attended Amherst where he was considered one of the finest athletes of an era, then went on to Harvard Business School. He became a vice president of Citicorp, then headed a small New York Stock Exchange company before dying in his forties after a protracted battle with prostate cancer.

HUMANITIES: And you have a wife who is an art historian.

LEACH: That’s correct. Deba has written a small book on Grant Wood, who’s Iowa’s leading artist, as well as Jacob Lawrence, who’s considered the premier African-American artist of the twentieth century. She is now an art counselor at our sister agency, the National Endowment for the Arts.

HUMANITIES: Is it from her that you learned a keenness for art?

LEACH: It is, and art history has become quite an avocation. I have not found reading about modern American politics particularly uplifting, so I read avidly about artists and art movements. Though I have never taken a course in the subject, I’ve become an enthusiast for the field and have developed a bit of a collector’s bug.

HUMANITIES: Do you have a favorite author of art history?

LEACH: I can’t say I have a favorite art historian, but I am quite impressed with Wanda Corn at Stanford and am convinced that the most perceptively written part of any American newspaper is the Friday art section of the New York Times. As for favorite periods, I’m particularly fond of the thirties and forties, the WPA and the New York school aftermath. Who would have suspected that Jackson Pollock would have been a protégé of Thomas Hart Benton?

HUMANITIES: And what did you study in college and grad school?

LEACH: In college, I studied political theory and wrote a thesis on the right of revolution. In graduate school, I concentrated on Soviet politics and economics. When I was in the eighth grade, I had to write a paper on what I wanted to do when I grew up. I asked the advice of my parents, and my father suggested I go down to the Davenport Public Library and check out a book on the Foreign Service. To my surprise, there were two such books at the library, and I wrote a small paper on joining the Foreign Service. From that moment on I remained bent on a State Department career. At Princeton I took Russian and while I had distinguished instructors I didn’t dabble that memorably in international politics, but at Johns Hopkins SAIS I had terrific mentors in Paul Linebarger in Chinese history and Hal Sonnenfeldt in Soviet politics, and at the London School of Economics my tutor was Leonard Schapiro, the world’s leading authority on the Soviet state.

Eventually I entered the Foreign Service, worked briefly at the Soviet desk, then in arms control. I was on rotation to be assigned to Moscow when I abruptly resigned in protest.

HUMANITIES: Why did you resign?

LEACH: The country was understandably convulsed with the Watergate issue and I determined that the day in the fall of 1973 known as the Saturday Night Massacre, when Nixon all but fired his attorney general (Eliot Richardson) in order to get a compliant appointee to fire the special prosecutor (Archibald Cox), symbolized the president putting himself above the law. All Foreign Service officers of any rank are presidential appointees, even though one enters through a competitive civil service exam, and I concluded that I couldn’t serve the president from that time on. So I found myself back in Iowa in a family business with my father.

Four or five months later, to my astonishment, the Republican county chairman from my hometown knocked at my door and said that the Republicans had no candidate against a popular young incumbent. He asked if I’d consider running. I thought it over for a few days and decided to give it a try.

I was comfortable with national policy issues but had no background in electoral politics, so this was quite an undertaking for me.

It takes awhile to get one’s bearing on the art of politics. In the end, I ran the best race I ever ran and got 46 percent of the vote in a Republican debacle year, a percentage which was higher than several incumbent Iowa Republicans received. My home was in the only overwhelming Democratic district in the state. But despite an initial poll that showed I was sitting on only 17 percent of the vote, I decided to try again two years later and was able to prevail, largely, I am convinced, because between elections I had married a lovely young woman who cared little about partisan politics but had vastly more friends than I.

HUMANITIES: Were there particular issues drawing you into politics?

LEACH: I had a view that how a candidate runs a campaign is sometimes as important as how he or she stands on any given issue, so I took a process stand that I maintained throughout my tenure: a commitment to run on small contributions and not take PAC or out-of-state money. The main reason I took this position related to lack of comfort in becoming indebted to special interests. But in the background of my concerns was also an unproven belief held then and to this day that the principal rationale for the Watergate break-in was a likely desire of the president to ascertain if the Democratic national chairman had in his papers evidence of a possible illegal contribution to a Nixon slush fund from a client whom the chairman in prior years represented.

On other issues, I basically have always been a progressive in international affairs, a moderate on social issues, and somewhat restrained on spending. Although a member of Congress can choose to speak out on any issue, the capacity to impact policy generally springs from committees of jurisdiction. Because committees dictate so thoroughly where a legislator can have the most influence, I gravitated to the international relations and banking committees.

Over the years, I was also active in many Congressional caucuses and cofounded one, the Humanities Caucus. But in my early years I was particularly active in the Arms Control and Foreign Policy caucus, which I came to chair. Paul Simon, Alan Cranston, and I were the most active caucus members during the Reagan administration. We used to speak out regularly against the Iran-Contra policy of the administration, and I issued a blistering caucus report on the history of U.S. policy in Central America. But for me the most consequential undertaking was advocacy of the nuclear-freeze movement against what had become an anti-arms control agenda in the early Reagan years that fortunately was reversed in the second Reagan term.

I’m one of the few who believe that largely missed in public understanding of the breakthrough in better relations with the Soviet Union under President Reagan was the fact that it occurred because of a multidecade American commitment to alliance preparedness and was precipitated by a president who was conciliatory as well as firm.

The person on Capitol Hill who Reagan listened most carefully to on Russian matters was neither a senator nor a congressman. It was our country’s leading cultural historian, Jim Billington, the head of the Library of Congress. Billington advised the president on how to accommodate Russian leadership sensibilities, how to engage as well as confront. The second-term change in direction on arms control—symbolized by sudden advocacy of a Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)—and use of Billington-ese to complement the straight talk about the need for a wall to come down were seminal factors in developing more credible U.S.-Russian relations.

Generations hence historians may come to credit Gorbachev as much as Reagan for the breakup of the Soviet empire, but my view is that the principal credit goes to the American people for sustained support for preparedness and the Russian people for recognition that their Leninist system simply wasn’t designed to serve their or the world’s interests.

HUMANITIES: What does it mean philosophically to be a progressive Republican?

LEACH: Conceptions of progressive Republicanism have shifted over time, as definitional contrasts within and between parties have shifted. When I entered politics, there was a well-understood cleavage between Goldwater conservatism and Rockefeller urbanism. Today, the conservative dynamic is more social issue-related than attuned to individual rights. If Goldwater were alive today, he would be perceived as a radically liberal Republican. He was an economic and individual rights conservative, pro-choice and pro-gay rights.

The new, disproportionately Southern conservatives who now give the most energy to the party have caused a shift in the type as well as philosophy of Republican legislative leadership. The conservative wing has always been the larger wing within the party, but there has generally been a substantial moderate wing as well. Today in Congress the moderate base has been eroded almost to extinction.

In the Democratic party an analogous circumstance exists. The liberal wing of the party is dominant. The moderate base is a bit larger than in the Republican party, yet it also remains quite weak. The ahistorical oddity in American politics is that at the congressional level both parties have become decisively less moderate. The great underrepresented group in American politics is the huge American center. This astonishing phenomenon is so remarkable because, from de Tocqueville on, people have noted that Americans are uncomfortable with the extremes.

As the parties move to the edges, the national legislature has changed dramatically. Members have no self-interest in compromise or centrist accommodation when the vast majority of House seats are so designed or gerrymandered as to be controlled by a single party. If, for instance, in a Republican controlled district a member moves to the center, that individual is likely to be challenged by a more conservative candidate in the primary. And if a Democrat moves to the center, that individual will find his or her career jeopardized by someone more liberal in a primary.

What is so underexamined in American politics is the nature of the primary process that produces party candidates and the nature of political party structures that provide organizational cohesion. Participation is so low that activists who are increasingly ideological rather than pragmatic carry the day.

What this means in Congressional decision-making is that the notion of a Hegelian dialectic—the thesis being advocacy of a position by one party, the antithesis being opposition by the other, the synthesis being a compromise between the two parties—is breaking down. Over the last generation, most of the significant legislative compromises now occur principally within the majority party, rather than between the two parties on Capitol Hill.

The country is becoming politically splintered, moving toward a political party model which emphasizes an opposition rather than a shared governing mindset of minority political parties in legislative chambers. When I entered Congress I had the view that all legislators shared responsibility for governing decisions. I felt that all should be free to agree or disagree with any approach of any other member of any party but should always approach issues with respect for those with whom one differed and with a desire to be constructive. Of all the confounding aspects of politics that have become accentuated over the past generation is the nihilist game of “gotcha” partisanship where anything that might bring credit to the other side should be opposed.

HUMANITIES: I’ve been reading through your speeches. What most distinguishes them, I think, is their frame of reference. It is that of a classical liberal arts education. Perhaps it’s related to your background in political theory, but I notice you’ll mention Thucydides one moment and John Locke the next. How do you think your education at Princeton and elsewhere has shaped your approach to life in general?

LEACH: We’re all shaped by family background, by education, and by life experiences. In my case, I was fortunate to have a wonderful family and access to a quality education. I had great teachers and was confronted with challenging ideas. But I do not think I became particularly academic in orientation until near the end of graduate school. There is a lot of irony in this, some of which is quite personal. I developed a severe arthritic problem that put me on crutches for several years when I transitioned from the LSE to the Foreign Service. This affliction ended my participation in athletic kinds of endeavors, causing me to turn a bit more inward. Whereas I’d been releasing a substantial amount of energy on athletic fields, I came to concentrate more intently on writing and analysis.

HUMANITIES: In your speeches, I also noticed that you often refer to human nature, which is kind of an unfashionable term these days. What do you mean by it?

LEACH: It’s impressive that our Founders were as much moral philosophers as political activists. Everything began with the notion of the nature of man. They were concerned with man’s tendency to accrete and abuse power, and that’s why we have a separation-of-power system. To the befuddlement of people around the world, we embraced a Montesquiean model for our national government, then replicated power-sharing arrangements among executive, legislative, and judicial branches at the state, county, and city levels. We thus have many overlaps between and within levels of government and inherent governing tensions. Decentralization as well as separation of powers characterize the American system, and all of this relates directly back to the Founders’ view of the nature of man.

The importance of governing systems and philosophies that underpin them is underscored in the twentieth century by the sobering recognition that two of the more sophisticated cultures in the world broke down into “isms” of hate. Germany, after all, in many ways was at the forefront of Western culture and Russia had impressive achievements in math, music, and, surprising to some, was at the cutting edge of modern art in the first part of the century. In terms of politics, lessons are clear. There are tendencies in individuals and political elites to lose track of civilizing values, especially in hard times, and it is difficult to reverse such trends.

In teaching I used to reference a precept that goes far back in history but no one seems to know precisely where—the seven deadly sins—and make a contrast between greed and pride. Greed may be the preeminent weakness of business classes, but pride is the primary weakness of politicians. Pride, I have observed, is more compromise-resistant than greed, which has a fundamentally pragmatic dimension. In business, for instance, one has to make rational decisions of mutual self-interest in order to advance commercial transactions, whereas in politics, there’s a reluctance to shift gears once decisions are made. The greatest strength of democracy in general is that when politicians err, the public can force corrections. Seldom does a politician shift gears of his own volition. But the ballot box is like a gear shift. It has a reverse as well as forward option.

HUMANITIES: So it takes humility to reverse one’s self and that humility is all too rare in politics?

LEACH: That is a valid observation. From my experience, as I look at my colleagues, the one commonality is that virtually everyone in political life gets fluent at public speaking. Too many get so good at it that they convince themselves that they know what they’re talking about. The fact of the matter is that most politics is quite shallow. There are so many issues that it is difficult for people in elected positions to be deep on anything. In this circumstance the art of representation involves listening to all sides but learning whose judgment to give the most weight to.

We all have illusions. There’s hardly an American who doesn’t assume they have good common sense and are good judges of character. Yet we all know people who we believe have little common sense and are terrible judges of character. In politics this kind of thinking is magnified. Everyone thinks they have fabulous common sense and are fabulous judges of character. You can’t break through this. One has to address issues from a human as well as an issue perspective.

HUMANITIES: Now, there’s an odd coupling of qualities in you that I’ve noticed. One is that you look back to the Founders and you talk about human nature. The Founders, of course, took a very dim view of human nature.

LEACH: They sure did.

HUMANITIES: But you have sort of an optimistic side and you sound often like a nice good-government politician, like when you emphasize integrity in politics and all sorts of other personal virtues. Are you an optimist? Do you secretly hold sunny views of human nature?

LEACH: Well, you have to be an optimist to have any hope for the future and, like our Founders, I lean to Locke over Hobbes. Hobbes, as you recall, assumed that man could never escape a state of nature, the jungle where life was “nasty, brutish, and short,” because he was so self-centered that he had no capacity to put himself in the shoes of others. Locke, on the other hand, held that man was rational and could see other perspectives, and thus could create a civil society where rules would govern disputes with third party arbitration.

The challenges of our Founders in establishing a governance structure were great, but the policy issues of our times are far graver. What differentiates us is that we are the first generation of people that has the capacity with weapons of mass destruction to self-jeopardize life on the planet. But the least understood aspect of international society is that at the same time that WMD issues hang over civilization so do new dimensional uses of less powerful weapons. In a world in which anarchistic techniques have become for the first time globalized, the more advanced a society, the more vulnerable it is to less sophisticated weapons. Small acts of a few can produce extraordinary consequences.

Every day commentary emphasizes the notion that we are in a globalized economy. But in politics the extraordinary power of localism remains. There seems to be something in human nature and in the human condition that wants to make locally cohesive decisions, even if seemingly irrational. So we have the phenomenon of the breakup of the Soviet Union and the Soviet empire. But at the same time Czechoslovakia won its independence, it split in two, and as the unifying threat of Russia receded, Yugoslavia became a multiplicity of states. In this context, we should not be surprised when outside powers intervene in local affairs, even with the best of intentions and no desire for empire, that local resentments will build.

Our challenge in so many areas of governance is to be attentive to the perspectives that the humanities provide. The lessons of history, recent as well as ancient, must be factored into policy matrixes that include philosophical considerations. To fail to think through the wisdom of our initial appeal to the opinions of mankind in establishing a new kind of framework for the rule of law to flourish, and to fail to reflect on the experiences of others as well as our own, has a tendency to magnify rather than solve problems. The relevance, for instance, of the French colonial experience in Algeria and Indochina is large, as is the counter-model that our most underrated president, Dwight Eisenhower, established of backing our closest allies, the British and French, out of Egypt.

Human nature may be much the same the world over but cultural experiences are widely different. Society, like the individual, is a reflection of both nurture and nature. Our understanding of the Islamic world was not great when extraordinary decisions were made in the wake of 9/11. But it would be a mistake to assume that at issue is simply an Islamic-Western “nurture” dichotomy. It appears to be the nature of people to want to make their own decisions, albeit, their own mistakes. Nobody wants to be directed from the outside, whatever the culture, whatever the governing religion or non-religion.

HUMANITIES: What are your plans for the National Endowment for the Humanities? Where are you leading us?

LEACH: I believe that culture is far larger and more powerful than politics. Not to pay attention to the humanities, whether history, philosophy, or literature, is a costly mistake. Take relations between states: If a country respects another society, greater opportunity exists to have credible relations; and if it doesn’t, there is a near impossibility of having constructive long-term relations. Culture comes first, and politics follows.

American culture encompasses a political system that provides through the electoral process for course corrections. We are in the midst of one that I consider quite wise. While it is always premature to assess a presidency before it fully unfolds, the direction this president is moving in internationally is extremely important for the future of the country.

I’ve never known the president to reference the word “humanities,” but he is the most instinctively humanities-oriented president since Lincoln. His speech in Cairo was one to the great humanities speeches of the modern era.

Following his lead, I believe NEH is obligated to move forward with what I have described as a “bridging cultures” initiative domestically as well as internationally. We have to pay more attention to the meaning of words, for they reflect emotion as well as thought. It is hard not to be perplexed with descriptions of the administration as “fascist” or “communist” or both, with suggestions of “un-American” activities and loose talk of “secession.” It is also disconcerting that the health care debate has declined to the point where liberal advocates claim that Republican alternatives amount to telling sick people to “die quickly.” These are dangerous conceptions with violent implications. We must do better or we will tear asunder our social fabric.

We are a society of many subcultures, some of which reflect cultural dynamics of people in other parts of the world. Diversity, often reflected in immigration, has historically been energizing for American society. But there can be challenges. An improvement in our relations to the Muslim world should include a better understanding and treatment of Muslim citizens in the United States. How we live up to our own ideals could have a lot to do with whether we are more likely to live under the rule of law or anarchy, the rule of civility or violence.

HUMANITIES: As someone with a congressional background in banking and finance and as the chairman of NEH you’re uniquely positioned to comment on how the economic crisis is affecting humanities institutions. What has been the effect on humanities departments, museums, history documentarians, and scholars?

LEACH: Well, in essence, the humanities are confronted with a triple whammy, and the first whammy is the general economy, and support for the humanities comes from the economy itself.

The second is the reduction in capacities of both the federal government and state governments, and the third is the change in priorities at many academic institutions, where resources are being increasingly directed to what appears to be more job-intensive vocational training.

There’s been a general trend away from the humanities. When you read of the early academics in America, they followed the European models. Students were required to study Greek, Latin, and theology. These no longer seem central to the humanities, but foreign languages? Foreign languages would be helpful for Americans to study.

I have a personal view that I think immigrants are best off in America learning English. If more immigrants knew English and more Americans knew foreign languages, the two would make quite a strength. Our immigrant population has helped us deal with the rest of the world.

I think America is going to want to really think through the importance of the humanities. There’s a cost to choosing a field of study, and there’s a cost to not choosing. If you take the humanities, the cost of not paying attention has enormous implications in foreign policy, I mean arguably trillion-dollar implications. The cost of not paying attention to issues of history and culture and languages has enormous commercial implications, arguably in the trillions of dollars.

And so my view is short-changing the humanities short-changes America.

HUMANITIES: Can you give me an example of a trillion-dollar consequence to not studying the humanities?

LEACH: Well, I think a student of Muslim culture would have been hard-pressed to advocate a war against a country that didn’t attack us in the Middle East. A student of China might well have developed a more realistic way of dealing with U.S.-Chinese relations over the last half century. These are very costly circumstances.

As far as challenges, a student of Korean affairs might have taken a very different approach to key moments in the U.S.-North Korean relationship, and that doesn’t mean that all of the decisions that have led to difficultly aren’t principally the accountability of a North Korean regime, but in retrospect, there could well have been changes in direction that we could have helped manage but didn’t.

HUMANITIES: Who are some of your favorite writers? What do you read for pleasure, aside from art history?

LEACH: Well, I am pretty old-fashioned. I read Mark Twain, and I read history. I just read a biography of Samuel F. B. Morse who, as you know, is considered the inventor of the telegraph, whether he actually is is still a little debatable, and Morse Code, which is less debatable. Surprisingly, he was also the greatest portrait painter of his generation and founded the National Academy of Design in New York. He was, and this is bizarre, a political nativist, an anti-immigrant, anti-people, pro-slavery politician who ran for Congress, and ran for mayor of New York on preposterous platforms.

HUMANITIES: Do you read any John Irving?

LEACH: Yeah. I have. Irving is a lover of wrestling.

HUMANITIES: That’s why I asked.

LEACH: Yeah. Absolutely. I mean, you have to respect those who are interested in subjects that one shares an interest in. But he is also an alumni and former faculty member of the University of Iowa.

Iowa, as you know, has the premier writers’ workshop in the country and we’re exceptionally proud of it and quite a poetry tradition, too. It also has the preeminent international writing program in the country. And Iowa City is an oasis of creativity, and I’m fortunate to be a part-time resident of that town.

HUMANITIES: Thanks for this interview, Mr. Chairman.