Planning Passive Updates to Improve Sustainability – Who’d Pass on That?!

LED lights and other electrical improvements helped reduce energy consumption.

Courtesy Abbe Museum

LED lights and other electrical improvements helped reduce energy consumption.

Courtesy Abbe Museum

When thinking about sustainable solutions to cultural heritage preservation, what comes to mind? Cutting costs through energy efficiency, incorporating alternative energy sources, mitigating risk of possible disasters (from HVAC failures to tornados), and devising more effective storage solutions could all be on your list.

When searching for solutions to maintaining a preservation environment, especially tackling those dastardly humidity fluctuations, implementing passive measures and updating your building envelope can help to balance control with the high energy or infrastructure costs that often accompany it.

A number of planning projects supported by NEH’s Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections (SCHC) grant program have helped cultural institutions realize that a combination of passive measures and envelope repairs is most appropriate. In some cases, this is because the building is a historic structure, while in others, this approach yielded the right balance of costs and benefits or enabled the organization to improve collection stewardship in the short-term while planning for larger projects.

Here, we will explore a few of these projects and the wide variety of forms that these “minor” changes have taken.

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute

The MWPAI was struggling primarily with fluctuations in humidity that closely mirrored the outside environment, even though its mechanical system maintained a relatively stable temperature. An SCHC planning project enabled the institute to contract two outside consultants. The first, an object conservator from the Williamstown Art Conservation Center, evaluated climate conditions and set goals for exhibition, storage, and office zones. She referenced the Canadian Conservation Institute’s Environmental Guidelines for Museums when determining the appropriate goals for climate standards. The second consultant, Intelligent Converted Energy, which specializes in energy-efficient and environmentally-friendly climate systems, identified sources of moisture seepage into the building, namely from the soil, return air paths, and the loading dock.

A passive change recommended by the conservator and implemented during the project was incorporating seasonal setpoint changes, which allow humidity and temperature targets to move up or down about 10 points seasonally, while keeping fluctuations to a minimum. Furthermore, the second consultant recommended some building upgrades including: enclosing, sealing, and insulating the return air paths for the HVAC; installing an air curtain in the loading dock; adding insulation to a ceiling cavity on the top floor that was a source of high moisture; treating glass windows with ceramic film; and sealing the floors of the basement and sub-basement.

The MWPAI has been able to implement a number of these suggestions in a short time, including a new, insulated return air duct that bypasses the problematic uninsulated paths and their accompanying moisture load.

Center for Jewish History

The Center for Jewish History (CJH) archival and museum collections are spread out over five combined buildings, and managed by five in-house, collecting partner organizations. Not only is that hard to control consistently– it’s a lot to monitor! The center’s “stacks” experienced greater humidity fluctuation than desired, as evidenced on environmental monitoring equipment and in occasional seasonal mold growth. Prior to meeting with consultants from the Image Permanence Institute (IPI), the staff watched several IPI webinars on “Sustainable Preservation Practices for Managing Storage Environments.” The consultants helped collections and building staff better understand the sources of their climate issues, including two hatch doors that had never been framed properly and were allowing free flow of air between the exterior and interior walls.

A number of passive changes were relatively simple to incorporate: collection items were moved away from walls to aid air flow; high-risk materials received protective casings; and the Archives experimented with nightly shutdowns of the HVAC system. While they concluded that a few more envelope updates were needed before continuing this particular strategy, the financial motivation was strong – they saved over $15,000 in one month. Those unused 32,720 KWH are the equivalent of greenhouse gas emissions from 56,572 miles driven in the average car!

Some building envelope updates were tested during the planning grant, while others were recommended for the future. One of the first was putting spray foam covered with stucco around the hatch doors to seal them properly. Others included installing gaskets on doors to and from collection areas. The center’s consultants also recommended capital upgrades, but even these “small” measures have the potential for substantial effect on both maintaining a safe environment for collections and saving money in the meantime.

Since the CJH’s grant ended, the team has continued to meet, along with new related staff. They have been whittling away at a punch list developed from the planning grant recommendations and have accomplished most of their short-term and even some of their mid-term goals. While nightly shutdowns have been tabled until further improvements are complete, they have incorporated seasonal setpoint changes for climate and incorporated protective enclosures for the most sensitive materials.

Reflecting on the project, Jennifer Sainato, Preservation Lab Manager, wrote that it “provided the Center for Jewish History with important information about its systems, allowed us to develop concrete goals for improvements, increased communication among the Collections Management and Building Operations teams as well as communication between the Center and its Partner collections, and acts as a ready-reference for ongoing planning and fundraising.”

Abbe Museum

The Abbe Museum was dealing not only with inconsistent temperature and relative humidity, but also with mechanical failures and resulting high energy bills. A planning grant allowed outside eyes (conservators, preservation environment specialists, architects, and engineers) to look into these issues comprehensively. They first compared climate data to industry standards put forth by the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers, specifically the “Museums, Galleries, Archives, and Libraries” section of its Applications Handbook. In the white paper, project director Julia Clark states that “The disconnect between what engineers and many in the conservation field tell us is OK and what loan agreements require has been highlighted as part of ongoing discussions and research in the museum and conservation fields, and played an important part in improving our understanding of what to expect and what variations were acceptable.” Some passive solutions included a concerted effort to close doors, rebalancing the flow of conditioned and unconditioned air, limiting the intake of unconditioned air to the hours when the building was occupied (and installing a CO2 alarm!), making seasonal setpoint adjustments, and monitoring the effectiveness of exhibit cases as environmental buffers.

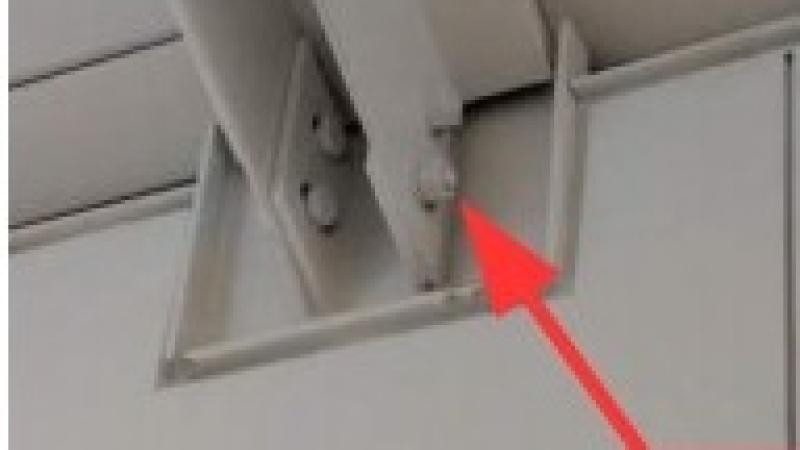

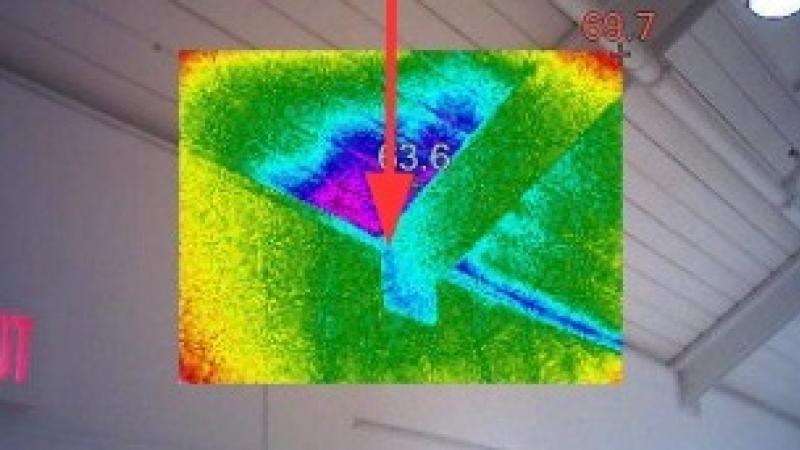

The museum’s planning grant led also to an SCHC implementation grant and an overall “Greening the Abbe” campaign, which funded thermal imaging and related insulation repair, as well as updates to the mechanical systems and a switch to LED lighting.

Carnegie Institute

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s anthropological collections have been stored in an area where it was difficult to control relative humidity adequately, although temperature remained steady. In a planning project, the museum’s internal Facilities, Planning, and Operations department realized that on cold days, the outside air could be used for the cooling function within the building’s mechanical system, that a chimney could be removed and sealed off, and that exterior doors needed new weather stripping. The department also did an infrared scan of the building envelope, updated mechanical controls, and instituted new procedures into their scheduled maintenance. These combined updates to the mechanical systems and envelope have “had a significant impact on the EORC utility bill,” states Sandra Olson in the white paper produced at the conclusion of the project.

“Passive” preventive conservation applies to more than mechanical systems and building envelopes. Project staff consulted with engineers, architects, and space planners to overhaul the building’s storage systems, too. The size of the collection rehousing project resulted in a number of innovative approaches, eventually supported through an SCHC implementation grant. But, on a small scale, a number of the methods that curators developed with a conservator, such as placing Tyvek dust covers over PVC frames to protect large 3D objects and creating micro-climates in storage boxes for small items, are relatively inexpensive solutions.

Bryn Mawr Special Collections

Bryn Mawr College’s collections include rare books, manuscripts, artifacts, and art. The college embarked on an SCHC planning grant to explore consolidating collection storage and addressing climate, lighting, and security issues all together. While the project’s focus was to develop a plan for collection consolidation, the consulting architectural firm, Samuel Anderson Architects, also offered suggestions of minor changes for the interim. Working alongside additional consulting engineers and security specialists, their recommendations included caulking and weather stripping exterior doors to seal the building better from outside air, pollution, and pests; adding UV filters to the fluorescent bulbs; exploring installation of motion sensors or rewiring so that lights could be turned off in collections areas when not occupied; and installing humidifiers and dehumidifiers in storage areas.

Bryn Mawr plans to move forward with large-scale renovations, and has incorporated many of the short-term recommendations for the time being, including purchase of dehumidifiers and humidifiers for the primary art and rare book storage space, purchase of equipment for temperature and RH spot checks, transitioning to cloud-based data loggers, and switching to LED lights and adding filter sleeves in many spaces. Project director Marianne Weldon, an objects conservator and the collections manager for art and artifacts, says that as they embark on more comprehensive renovations “having Anderson’s solid plan in hand will make both the overall building planning and the fundraising campaign much easier to manage.” She mentioned that the plan has also helped them identify needs prior to consolidation, in one aspect met “with a team of graduate and undergraduate students working on inventorying and rehousing the print, drawing and photograph collections.”

Would a year of dedicated planning help your organization determine cost effective and sustainable measures to better protect collections? Learn more about these projects in their white papers (below), and about the Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections program here.

Resources & Related Links:

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute (PF-230348-15) white paper

Center for Jewish History (PF-230326-15) white paper

Abbe Museum (PF-50034-10) white paper

Carnegie Institute (PF-50260-12) white paper

Bryn Mawr (PF-249697-16) white paper

What’s On Your Wish List? Archives Edition by Margaret Walker

Planning for Preservation with a Great Team by Margaret Walker