More than Medals: A Q&A with NEH-JUSFC Fellow Dennis J. Frost on the History of the Paralympics

The opening ceremony for the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics was held on August 24, 2021, exactly one year later than originally planned. Like so much that has occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, these Games are being discussed in traditional and social media as an “unprecedented” event. However, the Paralympics, and disability sports in general, have deep roots in Japan. I spoke with Dennis Frost, whose new book More than Medals: A History of the Paralympics and Disability Sports in Postwar Japan (Cornell University Press, 2020) chronicles this little-known history.

When Tokyo hosted the Paralympics in 1964, was the city an obvious choice? What were the immediate impacts of the Games in the city and region?

Tokyo was both the natural choice and an unlikely host. The Paralympics at the time were still relatively new, having only been launched in England in 1948. The first place to host them outside of England was Rome in 1960, soon after the Olympics were held there. Organizers’ early attempts to foster a closer connection with the Olympic Games meant that as the host for the next Olympics, Tokyo made perfect sense as the site for the 1964 Paralympics. However, before 1962 no Japanese athletes had ever participated in Paralympic events, and most people in Japan—including many of the eventual organizers for Tokyo’s 1964 Games—had minimal exposure to disability sports at all. In a sense, Japanese organizers for the 1964 Paralympics were starting almost from scratch but managed to put together an international sporting event for more than 350 athletes with disabilities in just a couple of years. That was an impressive accomplishment in itself and made for an amazing story that’s shared in More than Medals.

A large portion of the first chapter in the book is devoted to exploring the multi-faceted impacts of these Games, but for the sake of brevity, I’ll highlight just three examples here. First, Tokyo’s Games played a critical role in introducing the Paralympic movement to the Japanese population, establishing—for better or sometimes worse—approaches, patterns, and ideas that would continue to shape disability sports well into the future. On a related note, the 1964 Paralympics laid the foundations for the continued promotion and development of sports for those with disabilities in Japan. For instance, what eventually became the Japan Sports Association for the Disabled (now called the Japanese Para-Sports Association) had its roots in the Tokyo Paralympic organizational efforts. Beyond the realm of sports, these Games demonstrated to a wide domestic audience that people with disabilities were more than stereotypical patients stuck in hospitals or their homes, and they also helped introduce new approaches to rehabilitation that had profound effects on the lives of many people over the longer term.

What were the Far East and South Pacific (FESPIC) Games, and how did their mission and goals differ from the elite competition found at the Paralympics?

The Far East and South Pacific Games for the Disabled were developed in and first hosted by Ōita, Japan, in 1975. Much more commonly known as the FESPIC Games, they were essentially a regional version of the Paralympic Games, but they were initially envisioned as modest events that could be held even in countries that lacked rehabilitation sports programs, which was the case for much of the region. For the next three decades the FESPIC movement served as the driving force promoting sports for people with disabilities in the world’s most populous region, and they repeatedly broke new ground by making international sports competitions accessible for people with disabilities who might not otherwise have participated in sports. One of the original goals for FESPIC was to provide funding to bring new athletes to the Games from countries that could not normally afford to send athletes abroad. In contrast to the Paralympics today, which are geared towards very high-level, elite competition, the FESPIC Games maintained a commitment throughout their history to making sports available for ever more people, as exemplified especially by the official 30-percent novices rule, which required that roughly a third or more of the participants at the Games be competing internationally for the first-time. In the end, the FESPIC Games were held nine times in eight different countries before being replaced in 2010 by the ongoing Asian Para Games. Despite their significance, few people today have heard of FESPIC, which explains why Japan’s roles as both the base of operations and a major source of financial support for these Games are not very well known either.

What role does Ōita Prefecture play in this history of disability sports, and in promoting the inclusion of those with disabilities in society?

Ōita Prefecture, which is located on the island of Kyushu, roughly 600 miles from Japan’s capital of Tokyo, is not the type of place that most people (including me initially) would usually think of as central to the history of disability sports. But I soon discovered that the region’s reputation as “Japan’s cradle of disability sports” was well deserved. Home to numerous naturally occurring hot springs, Ōita has long been a destination associated with treatments for various physical ailments. That longer history played a key role in its emergence as a center of rehabilitation for people with disabilities in the years during and after World War II. In the lead up to the 1964 Tokyo Paralympics, it was a competitive sports event for athletes with disabilities organized in Ōita in October of 1961 that helped convince organizers that hosting the Games in Tokyo might be more feasible than they had originally anticipated. As noted, Ōita served as the host for the first FESPIC Games in 1975, and it was also the home of the FESPIC Movement’s base of operations for more than three decades. In 1981, the Ōita International Wheelchair Marathon was founded to celebrate the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons. As an international, wheelchair-only, competitive road race, this marathon was the first race of its kind anywhere, and it has continued to be held every year since 1981. The race welcomes hundreds of domestic and international wheelchair racers annually, making it one of the world’s largest wheelchair marathons. In its more than four-decade history, the Ōita International Wheelchair Marathon has regularly hosted the biggest names in wheelchair racing circles and witnessed multiple world-record performances.

Beyond sports, Ōita is also the home of Taiyō no Ie (“Japan Sun Industries” in English). Established in the aftermath of the 1964 Paralympics, Taiyō no Ie was a factory, in the city of Beppu, specifically created to provide an accessible place of employment for individuals with disabilities. Over the course of its history the initial factory expanded dramatically, establishing partnerships with major Japanese corporations and providing a model for other facilities launched by the Japanese Health and Welfare Ministry. Today, Taiyō no Ie is one of the largest factories in Beppu and has expanded to other sites in Ōita and other prefectures. The original location boasts a complex of factories, housing, sports facilities, and other accommodations that have long facilitated independent living and social integration for people with a variety of disabilities.

One person is at the center of many of these moving pieces, from the 1964 Tokyo Games through the next twenty years. What importance did Dr. Nakamura Yutaka have to these events and the movement?

Although it’s important to acknowledge that many people played pivotal roles in this history, it would be hard to tell this story without taking Dr. Nakamura’s contributions into account. He was a native of Beppu in Ōita Prefecture and an orthopedic surgeon with a particular focus on rehabilitation. Nakamura became interested in disability sports in 1960 when the Japanese Health and Welfare Ministry sent him on a six-month overseas trip to study facilities in Europe and the United States. In particular, Nakamura’s experiences at England’s Stoke Mandeville Hospital where the Paralympics originated proved transformative, turning him into a Paralympics advocate for the rest of his life. Nakamura was intimately involved in many of the events and developments discussed previously. It was his organization of the event in Ōita in 1961 as well as active lobbying and recruitment that helped reignite efforts to bring the Games to Tokyo in 1964. The establishment of Taiyō no Ie, FESPIC and the Ōita International Marathon were also part of Nakamura’s handiwork. His ever-growing network of contacts and supporters and his tireless promotional efforts for these projects explain why he’s been dubbed the “father of the Paralympics in Japan.” Perhaps my favorite example of Nakamura’s wholehearted commitment is the story of how he sold his own car in 1962 to help pay for Japan’s first ever participation in international disability sports competitions in England.

What changes occurred in how Japan viewed disability sports between the 1964 Tokyo Games and the 1998 Nagano Winter Games?

At a very basic level, one of the biggest changes stemmed from the fact that Japan’s involvement with disability sports had become far more common, even if it was not yet part of mainstream awareness. By the 1990s, Japanese athletes were regularly engaging in a wide range of disability sports at home and abroad, and, as the examples of FESPIC and the Ōita Marathon demonstrate, Japan had also become an international disability sports pioneer in its own right. Organizers for Nagano were also able to capitalize on the fact that the planning phase for these Winter Games coincided with increasing disability rights activism in Japan and also overlapped with the U.N. Decade of Disabled Persons (1983–92) and the Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons (1993–2002). The increased domestic activism and these international campaigns pushed the Japanese government to adopt international “normalization” ideals as guidelines for revising several of its disability policies and laws in the 1980s and ’90s.

Another notable change from Tokyo 1964 to Nagano was related to an increased emphasis on elite-level competition in connection with the 1998 Games. This change reflected developments in the international Olympic and Paralympic movements, which were both trending toward increased professionalization. For the Nagano Paralympics this shift was exemplified in formal promotional efforts and represented a significant break from the earlier focus on sports as a form of rehabilitation. Whereas organizers in 1964 tended to downplay the importance of competition to focus attention on the medical and social benefits, by 1998 organizers were repeatedly emphasizing that, like the Olympics, the Paralympics were a competitive sporting event involving some of the world’s most elite athletes. The Nagano Paralympics also marked a turning point in terms of both the amount and nature of media coverage. In many respects, the 1998 Games broke new ground in Japan, while also establishing an impressive foundation for what would become Japan’s next Paralympic event, the Tokyo 2020 Games.

What changes have you been seeing between the 1998 Nagano Winter Games and the 2020 Tokyo Games?

I tend to think of the changes we’ve been seeing in the lead up to Tokyo 2020 as an acceleration or amplification of things that were already starting to happen in 1998. That said, there have been several noteworthy developments. Some of the biggest changes for Tokyo 2020 were tied to the closer integration of the International Olympic Committee and the International Paralympic Committee beginning in the early 2000s. As a consequence of several agreements, potential host cities must now include their plans for the Paralympics and address how the city will meet the needs of individuals with disabilities. During Japan’s earlier Games, the Paralympics were still essentially voluntary, add-on events. On the domestic legal front, changes to several of Japan’s disability-related laws, including passage of an antidiscrimination law in 2013, had a direct impact on organizational efforts for the Games. The years leading up to the 2020 Games in Japan also witnessed a combination of increased funding for disability sports, new forms of organizational support, efforts to integrate non-disabled and disability sports under a single government ministry, and legal changes related to sports in general. These sorts of domestic changes in Japan meant that the 2020 Games were being organized and held in a very different environment than had been the case in any of Japan’s previous encounters with the Paralympics.

Two other developments merit particular notice as well. First, like Nagano’s Games, the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics were often linked to broader efforts to improve accessibility in Japanese society. But these efforts in connection with the 2020 Games have been amplified by Tokyo’s standing as the political, economic, and media capital of Japan, as well as the intensifying demographic pressures that Japan has faced since 1998. Indeed, the 2020 Games have been repeatedly and explicitly linked to concerns about addressing the needs of Japan’s rapidly aging population and shrinking workforce. Second, with even closer ties to the Olympics, the Tokyo Paralympics have increasingly emphasized elite performance, an approach apparent in the original bid materials which cited plans to integrate the athletes themselves as key figures in the marketing and promotion of the event. Organizers’ approaches proved a boon for athletes and disability sports in Japan, as the Paralympics and Paralympians—past, present, and future—have garnered an unprecedented degree of popular and media recognition in connection with Tokyo 2020. Based on what I was already seeing in the years leading up to the Games, these Paralympics and their athletes were on track to be the best documented ever. Of course, the pandemic has added a degree of uncertainty that no one could have anticipated.

How and where did you conduct your research for this book? Was it done in the archives, in conversation with athletes or organizers, neither, or both?

The research for this book involved a combination of sources, methods, approaches, and sites. The bulk of my materials were in Japanese and only available in Japan, something which made support from NEH essential. Unfortunately, a lot of the archival materials were only available in fragments that were scattered at different locations all over Japan. It took me a while to track everything down, and then even more time to read through everything I’d found and piece together the different stories. A number of the larger events produced official reports, which were key sources, but to help me fill in gaps and explore other perspectives, I also worked with a wide variety of historical Japanese media coverage and other less formal accounts. Several contacts and archivists in Japan proved critical in helping me track down rare materials, including unique documentary footage, NGO newsletters, and firsthand accounts. I also arranged interviews and conversations with a mix of athletes, organizers, and journalists who were involved with disability sports and these events. One of the most exciting was an interview with Suzaki Katsumi, one of the Japanese athletes who competed in the 1964 Paralympics. Site visits to Tokyo, Kobe, Ōita, and Nagano gave me a chance to explore local archival materials and provided a better sense of the venues for all of these events. My personal observations of the 2016 Ōita International Wheelchair Marathon and promotional events in Tokyo during the first half of 2017 provided numerous insights that wouldn’t have been clear from the other materials I was working with. Because of language barriers, many people outside of Japan are not very familiar with Japan’s rich and important history of involvement with the Paralympic Movement. I hope More than Medals helps change that.

Did you uncover any surprises in your research?

Perhaps the most surprising and in some ways challenging thing was the extent to which my potential source materials were scattered or even lost. For many years the work of simply keeping disability sports events going with minimal staffing seems to have precluded concerns about long-term preservation of archival records in Japan. Fortunately for future researchers, I think that has begun to change. In terms of content, many things surprised me, but four stand out. First, as I noted, I was really struck by the central role that Ōita played in this history. It was not a place I’d ever been before, and not one I would have initially imagined as a groundbreaking region. It’s a terrific example of why we need to remember to look to the “peripheries” as sites that can become true drivers for change. On a related note, I was really intrigued when I realized how much attention disability sports received in local media outlets in Japan. While the national media tended to overlook disability sports for decades, throughout that time local newspapers and reporters were often providing some of the most detailed and nuanced coverage of athletes with disabilities. This again would have been something easy to miss given the traditional dominance of urban centers in Japan’s media markets.

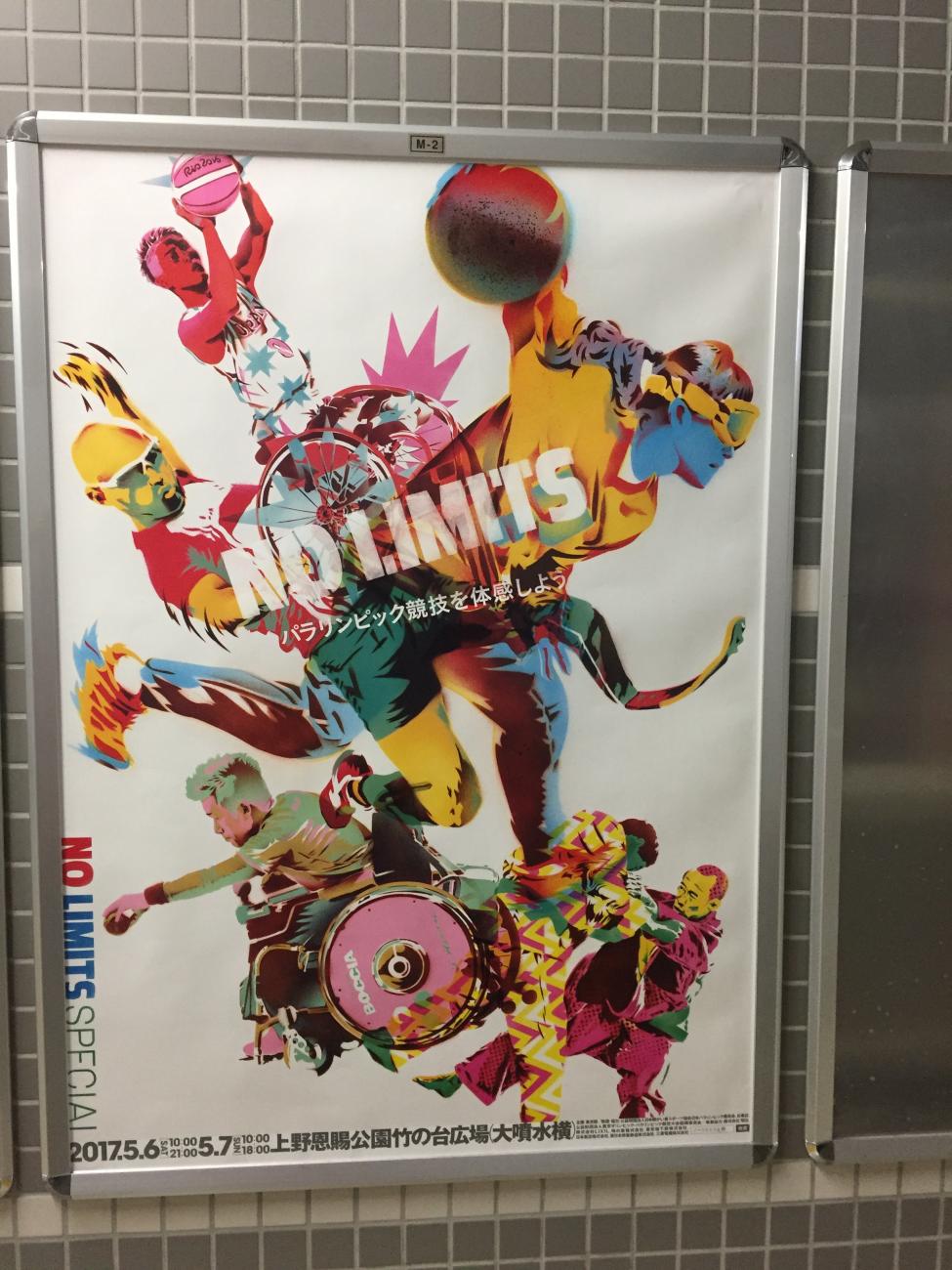

I was also surprised to find that the connection between disability sports and the promotion of barrier-free ideals in Japan is older than most people realize. I initially expected to see this element mostly in connection with Japan’s more recent Games, but I found people in my research discussing this idea for both the 1989 Kobe FESPIC Games and the 1998 Nagano Paralympics. Finally, while my family and I were living in Tokyo in 2017, we were really amazed by the attention that the upcoming Paralympics were receiving. Since the Paralympics and disability sports just don’t get that kind of attention in the United States, it took us all by surprise and made it hard not to get excited about the potential for the upcoming Games. Based on what I’ve seen more recently, it seems that the pandemic has understandably dampened much of that earlier enthusiasm in Japan.

What athletes or events are you most looking out for and forward to at this year’s Games?

Having met a number of athletes and seen a lot of disability sports over the course of this project, I’m somewhat hesitant to mention specific people or events to avoid unintentionally leaving people out. That said, I know that at least two of the athletes featured in the last chapter, Tsuchida Wakako and Tani Mami had qualified for the Games, so I’ll certainly be looking out for their competitions. Like many others, I had originally planned to attend in person and had been lucky enough to secure tickets to several events including boccia, rugby, tennis, basketball, and track and field. For obvious reasons, I won’t be able to attend any of these competitions now. Media coverage of the Paralympics in the US is supposed to be better this year than it has been in the past, but I still don’t know how many of the competitions I’ll be able to follow from afar. After seeing some of these events and others during previous stays in Japan, I suspect that the Japanese teams and athletes are going to be tough competitors this summer.

Now that More than Medals is finished, what’s next?

I’ve got several essays and articles related to particular elements of this history that I’m working on, and I’ve also started writing my next book, about Dr. Nakamura Yutaka and his role as a disability advocate. Aside from his work on sports, he was also pivotal to the development and expansion of Taiyō no Ie and events like the Abilympics, an international vocational skills competition for people with disabilities. Nakamura was quite prolific and very engaged in rehabilitation activities internationally as well. He’s a well-connected, fascinating, yet complicated individual. I think people would be interested in learning more about him, his ideas, and his work both within Japan and beyond.

Dennis J. Frost is the Wen Chao Chen Professor of East Asian Social Sciences at Kalamazoo College in Kalamazoo, Michigan. To support research for More than Medals: A History of the Paralympics and Disability Sports in Postwar Japan (Cornell University Press, 2021), Frost received both a Summer Stipend (FT-228739-15) and a NEH-JUSFC Fellowship for Advanced Social Science Research on Japan (FO-232442-16), a program administered by NEH on behalf of the Japan-U.S. Friendship Commission. The program aims to promote Japan studies in the United States, to encourage U.S.-Japanese scholarly exchange, and to support the next generation of Japan scholars in the United States. For more information on the Fellowship for Advanced Social Science Research on Japan program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.

Cornell University Press won an additional award (DR-278092-21) to make More than Medals available as a free ebook through the NEH’s Fellowships Open Book Program.. By taking advantage of low-cost ebook technology, this program allows teachers, students, scholars, and the public to download or redistribute outstanding humanities books at no charge For more information on the Fellowships Open Book Program, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.