Fans of American horror movies and television shows have likely noticed that zombies—the most popular supernatural subject of the first decade of the 2000s—are on their way out. Spirits and ghosts are slowly taking their place. I trace the transition to the first season of the now-popular American Horror Story (2011). Although the series has not enjoyed the same viewership as the wildly popular zombie hit, The Walking Dead, which premiered around the same time (2010), its airing marks the changeover. From the vantage of the 2020s, The Walking Dead seems like a eulogy to the previous decade, which featured rapid-fire zombie hits: 28 Days Later (2003), Resident Evil (2002), Dawn of the Dead (2004), Shaun of the Dead (2004), I Am Legend (2007), Zombieland (2009). The list goes on.

In hindsight, the first season of American Horror Story feels like an inauguration. It featured a house that traps the spirits of those who die under its roof. The affliction is rooted (spoiler alert) in the fact that the home’s original owner operated a twisted 1920s basement abortion clinic to the stars. The story, which echoes Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House, was a hit, and the series is now in its tenth season. More recently, Jackson’s novel served as the source for the critically acclaimed 2018 Netflix series that shares the novel’s title, only this time Hill House is haunted by the ghosts of family dysfunction. In this regard at least, ghosts themselves are not the only dead things back in fashion: old ghost stories (like Jackson’s) are, too. In the wake of this transition, a rash of haunting stories have filled our streaming platforms: It Follows (2014), Ouija (2014) and its sequel Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), Hereditary (2018), Fear Street (2021). The list goes on.

If horror movie monsters are metaphors for our collective anxiety (I think they are), then the shift is telling. It represents a move from fears about ideological polarization (the brainwashing/eating that divides humans into zombie and not-zombie) to fears about the past coming back to harm us. Yet American ghost stories are not morality plays. Their common ancestor is Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart (1843), a story about a murderer haunted by the cardiac apparition of his victim reminding him of his sin. It is not, in other words, a story about the suffering of the poor victim. In a reactionary register, this new fear of ghosts might reflect anxieties about the #MeToo movement and “cancel culture.” Or, in a collective register, American ghost stories may reflect anxiety about sins related to colonization, westward expansion, racism, and so on. Because America was founded on a break from a monarchy and hereditary forms of power, one of the most terrifying things Americans can fathom is being accountable to hereditary lines—being haunted, in other words, by the sins of the father.

American art has long investigated this particularly American form of horror, and it seems curators are starting to pay attention, too. “Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art,”—an NEH-funded exhibition that began its tour in 2021 at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, then traveled to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, and is now on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Art from February 19 through May 15, 2022—is all about ghosts and spirits and things that go bump in the night. It was on view in Louisville in time for Halloween, which maybe feels like a gimmick but is exactly right. Too often, museum space comes across as a clinic for cold examination, a space hostile to situated, affective experience. But ghosts require ambiance.

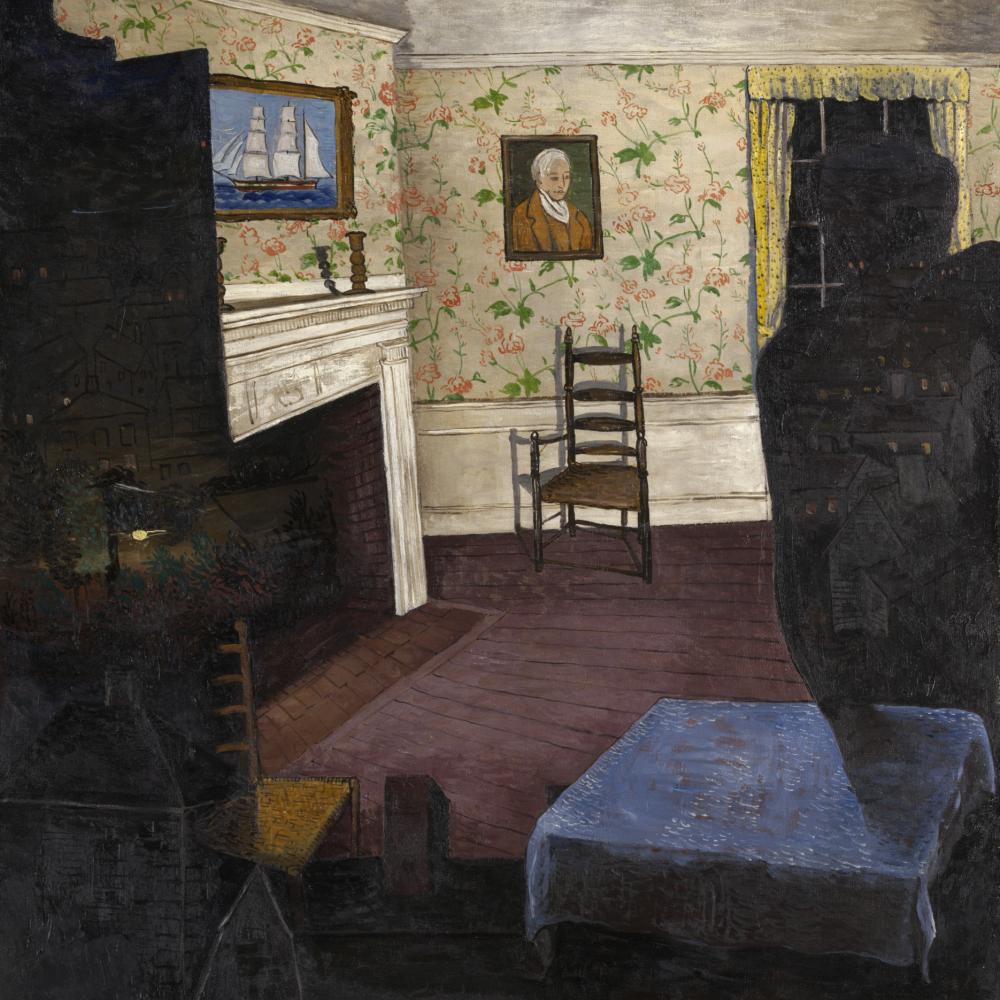

One particularly compelling installation in that regard is Whitfield Lovell’s Visitation: The Richmond Project (2001). The work takes the form of a painstakingly reproduced sitting room from the Jackson Ward community in Richmond, Virginia. Jackson Ward was a historically Black district that became home to many freed slaves after the Civil War. It was also one of only a handful of communities across the United States in the early twentieth century where Black citizens could build businesses and accrue wealth. However, in the 1940s and 1950s, Richmond’s all-white legislature imposed a series of structural changes to the area, including a highway bypass and the destruction of single-family homes in favor of public housing, all of which strangled the community. Lovell’s installation straddles the time before and after this governmental intervention. The parlor room feels both from our time and before. It is composed of wood and furniture from Jackson Ward’s past, including a table and piano, and recreates scents and sounds one might have experienced there. But the space is also old and worn. It looks like a historic place, yet it is not a recreation of life in the past but rather a parlor haunted by it.

Most ghost stories are situated this way, between today and yesterday, between the contemporary and the long past. Indeed, most ghost stories start in the middle. A family buys a house, a group of teenagers return to summer camp, or a young couple breaks into an abandoned psychiatric clinic. Strange things start to happen. We eventually learn (sometimes in the middle, sometimes at the end) that once upon a time something bad happened in this place—we learn how it all started. Ghosts, we might say (as Jacques Derrida did) are time out of joint. When a ghost first arrives on the scene, it is already a return of the deceased. But, of course, the deceased was, before death, not a ghost. So the apparition is impossibly both something new and something old. Maybe American art is like that too?

There is a lot of “realism” in “Supernatural America.” Portraiture abounds. There’s James McNeill Whistler’s eerie Arrangement in Black (The Lady in the Yellow Buskin) (circa 1883), Andrew Wyeth’s spectral The Revenant (1949), Ivan Albright’s The Vermonter (If Life Were Life There Would Be No Death) (1966–77), Allen Campbell and Charles Shourds’s Azur the Helper (1898), and lots of artifacts of paranormal investigation, including various slates with “automatic writing and portrait drawing” (circa 1910–20). We shouldn’t be surprised. Portraits are creepy. If given enough time, they all become death masks. But portraiture also offers us a persistent form of representation in the modern and late modern eras—eras that largely tried to abandon verisimilitude (art looking lifelike). That is one version of the history of modern art: The abandonment of illusionistic/realistic art in favor of real things like paint and canvas and material, which necessarily meant abstraction. Yet realism never really went away. We will always need portraits of presidents and board members and donors. And who doesn’t like to be tricked sometimes? But when representational art crops up in the modern era, it sometimes looks like the return of a thing we repressed—something older that we tried to get rid of but couldn’t. It appears, in other words, like a ghost.

“Real,” in this respect, is a haunted term in the exhibition. And that haunting begins at precisely the most conflicted moments of American history. There are, for example, a great number of objects made in the 1860s and 1870s. Some grapple with the Civil War itself. This makes sense: Lots of death means lots of new ghosts. Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s Angel on the Battlefield (1864) is one such painting. It depicts the aftermath of a deadly Civil War battle. Soldiers on both sides of the divide lie dead or dying, while an angel above, carried in on a dark storm, takes note in the Book of Life. The image itself is clear enough, but the meaning is ambiguous. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Book of Life is a register of all souls destined for heaven. Is the angel consulting the book to determine which souls to carry to paradise? Or is she blotting out some of the names—an indication that fighting for the wrong side has doomed certain soldiers for eternity?

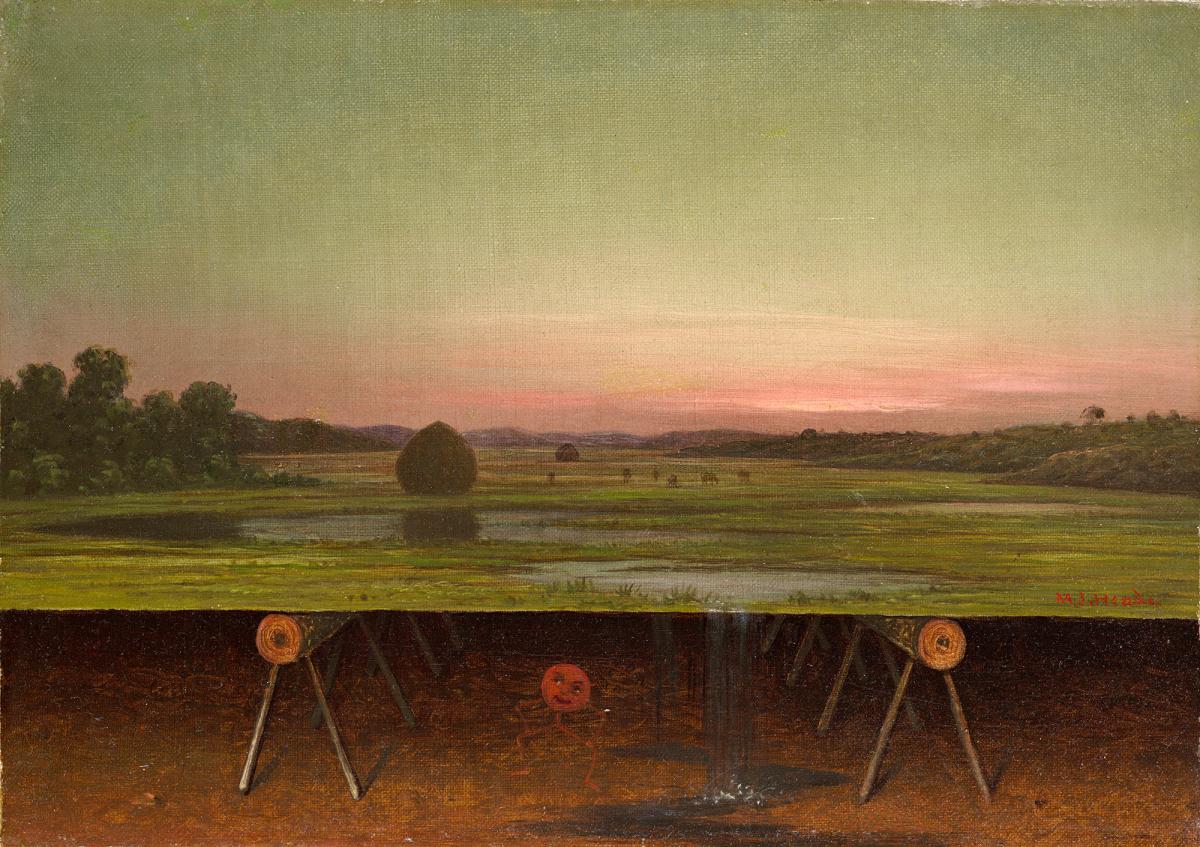

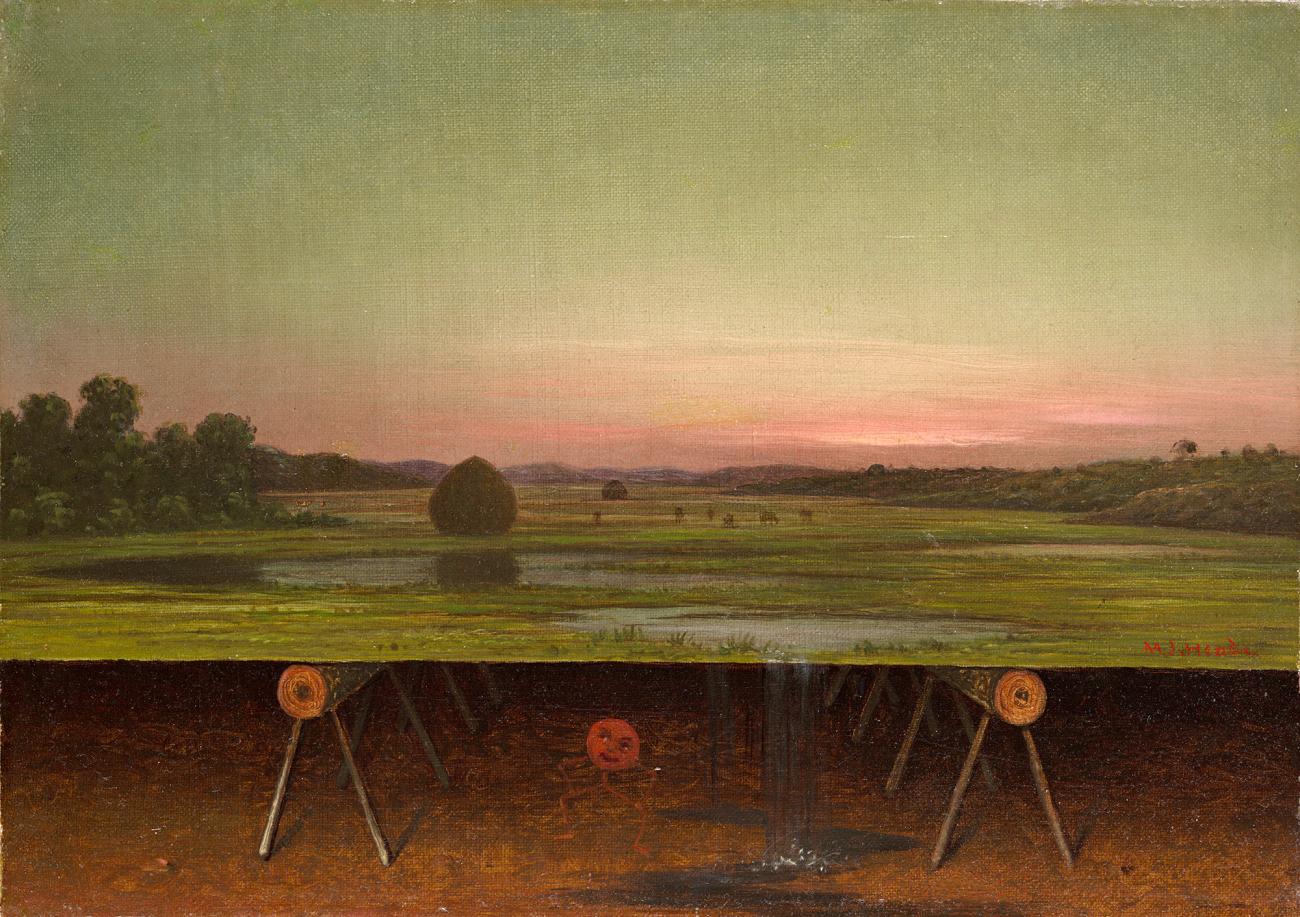

Where this wartime subject is perfectly appropriate to its moment, just as many artworks seem to have nothing to do with war. One particularly strange painting is Martin Johnson Heade’s Gremlin in the Studio (circa 1865–75). Heade was a well-known landscape painter and an amateur scientist (he really liked hummingbirds). During the Civil War he left for South America to paint landscapes. After, he moved to Florida to paint birds and flowers. Almost every one of his works is a representational, nearly scientific study of these tropical lands and their flora and fauna. Gremlin is no different—except that it depicts a painting of farmed swampland. That is, the landscape itself (signed on the bottom) is rendered in the composition as a physical painting propped up by two sawhorses. This painting, in turn, appears within a larger painting of the artist’s studio and is haunted, underneath, by a crudely rendered “gremlin.” This is a strange composition for the artist. Where is the “real” in this picture? Is it in the space of the representationally rendered landscape? The one that is so obviously a painting? Or is it in the space of the studio, which includes a fantastical gremlin? Obviously, a naturalist like Heade would not want us to mistake his supernatural gremlin for a real animal—the subjects he painstakingly depicted in almost every one of his other works. And how might this relate to the American Civil War?

This exhibition suggests that in these most conflicted American moments, all work, all life, becomes haunted. Even a landscape painting in Florida. The haunting, here, is effected by an anxiety of representation—an anxiety about truth in painting, and about the fact that all art, even “realistic” art, is an illusion. It, of course, has nothing to do with the Civil War, but it also has everything to do with the Civil War: This painting captures the moment in which even the American landscape becomes haunted.

You might rightly ask why this moment—the moment in which slavery ends—is the moment of our collective haunting. Why not earlier—perhaps 1619, when the first slave ship arrived in Jamestown? But that’s not how ghost stories work. Haunting is the past threaded through the present. It is not what happened but what is happening. The ghosts of slavery that will haunt America after the Civil War look like Jim Crow and redlining. A similar story can be told through many artworks that come from the 1920s and ’30s or the 1950s and ’60s. Each moment is a turn away, in American political and social life, from sins of the past into the ghosts of the present.

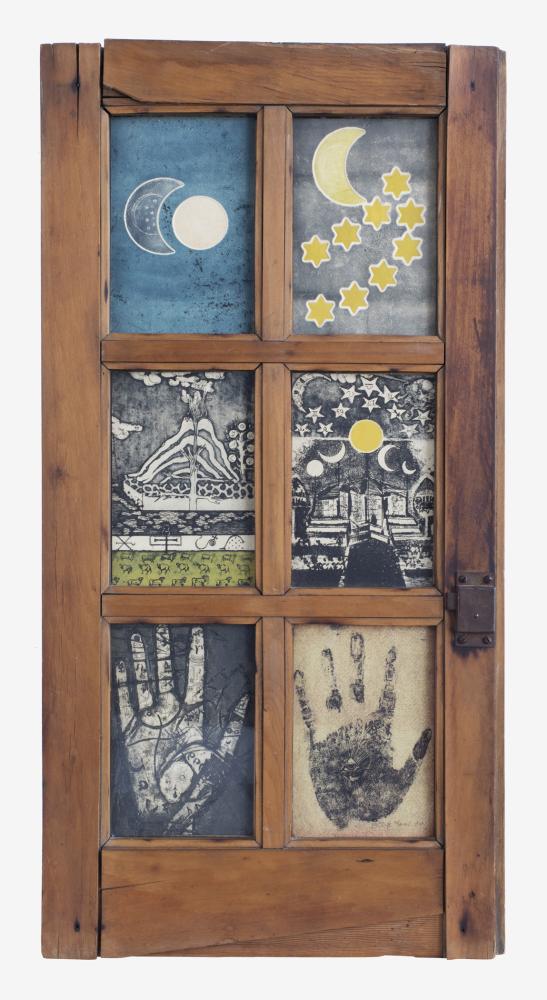

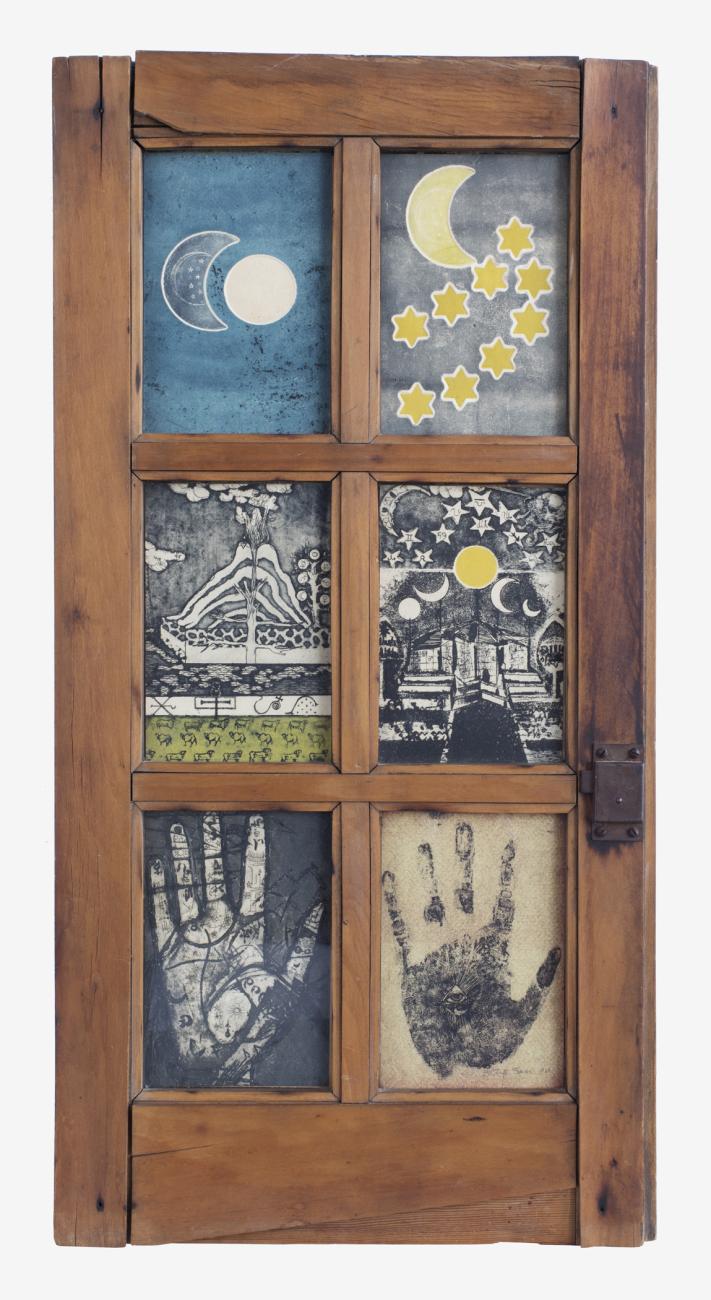

Not all hauntings are bad, I should note. The exhibition is careful to show that for many women artists, haunting can be a source of power. This is how the exhibition frames Betye Saar’s assemblages, works like The View from the Sorcerer’s Windows (1966) and Spirit Catcher (1976–77). There is much made of the word “medium” here—itself a haunted term with more than one meaning. Artists use various media to channel their subjects, but a medium is also someone with extraordinary access to the spirit world. The exhibition reminds us that for much of American history, women played the role of “medium,” serving as mystics or psychics, a profession that afforded many a source of income but also limited their role to passive vessel instead of a creative force. In that regard, we should take note that a renewed interest in spirits and haunting dovetails with the popularization of many previously unsung women artists, most notably the spiritualist Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), championed in the Guggenheim exhibition, “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” (2019), and Agnes Pelton (1881–1961), celebrated in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exhibition “Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist” (2020). Renewed interest in the spiritual, in other words, is not limited to Netflix. Although this is not a comprehensive account of this exhibition or of the phenomenon of American supernatural art, I want to suggest that at our most conflicted moments, the dead come back to haunt us. And if I am correct, we should take note: In American popular and artistic life, ghosts and their stories are on their way back.