Rochester, in western New York state, is a serious place, known for its harsh winters and for being home to Eastman Kodak, Bausch & Lomb, and the Rochester Institute of Technology. The city also has a playful side.

A natural sand beach within city limits opens onto Lake Ontario and offers swimming, fishing, boating, and, yes, a playground. Even more telling, Rochester is where the National Museum of Play, also known as “the Strong,” interprets and exhibits more than two hundred years of toy history.

The museum’s namesake, benefactress, and inspiration are one and the same, Margaret Woodbury Strong. An avid collector of dolls, Strong was heiress to a wealthy family that wisely got out of the buggy-whip business and invested early in Eastman Kodak. As the camera and film company’s earnings rose, so did the family fortune.

Born in 1897, Margaret traveled widely as a girl and caught the collecting bug from her parents. In 1920, she married Homer Strong, and the couple moved into a thirty-room mansion they called Tuckaway Farms in Pittsford, a suburb of Rochester. By the 1960s, her collection of dolls, toys, and other household objects numbered about twenty-seven thousand. Margaret added two wings to her mansion to accommodate the growing collection and even resorted to covering the swimming pool and using it as a vault for some of the overflow objects. In 1969, the Margaret Woodbury Strong Museum of Fascination was established, the same year of her death.

After Margaret died, her money and collection went to found a larger museum. Thirteen years later, the Strong Museum opened its doors at One Manhattan Square and now houses 520,000 toys, games, and artifacts, and is home to the National Toy Hall of Fame.

It was raining heavily the day I visited, and the museum was packed with children of all ages playing with, on, over, and under the exhibits. Children seek out the Play Lab, Skyline Climb, and Wegmans Super Kids Market, all of which require balance, challenge their motor skills, and test their navigational aptitude. Other exhibits place children on a par with superheroes and evaluate kids’ own superior mental acumen and superior strengths. Play need not be quiet activity, and at the Strong it is not. The place is loud, exuberant, and unbridled. Adults, meanwhile, gain context and historical background from exhibits on board games, building blocks, video games, dolls, toy cars and farms, and model trains.

Exhibit labels at the Strong are to the point and convey a few basic facts. The labeling for the “father of home video games,” Ralph Baer, zeroes in on his 1966 laboratory work with an oscilloscope—an electronic test instrument akin to a television screen—which led to his eureka moment and the eventual creation of Magnavox Odyssey, the first home video game console. Atari’s immensely popular video arcade game Pong followed in 1972. Legal battles loomed for a while as to who, exactly, the originator of Pong was. Baer came out on top.

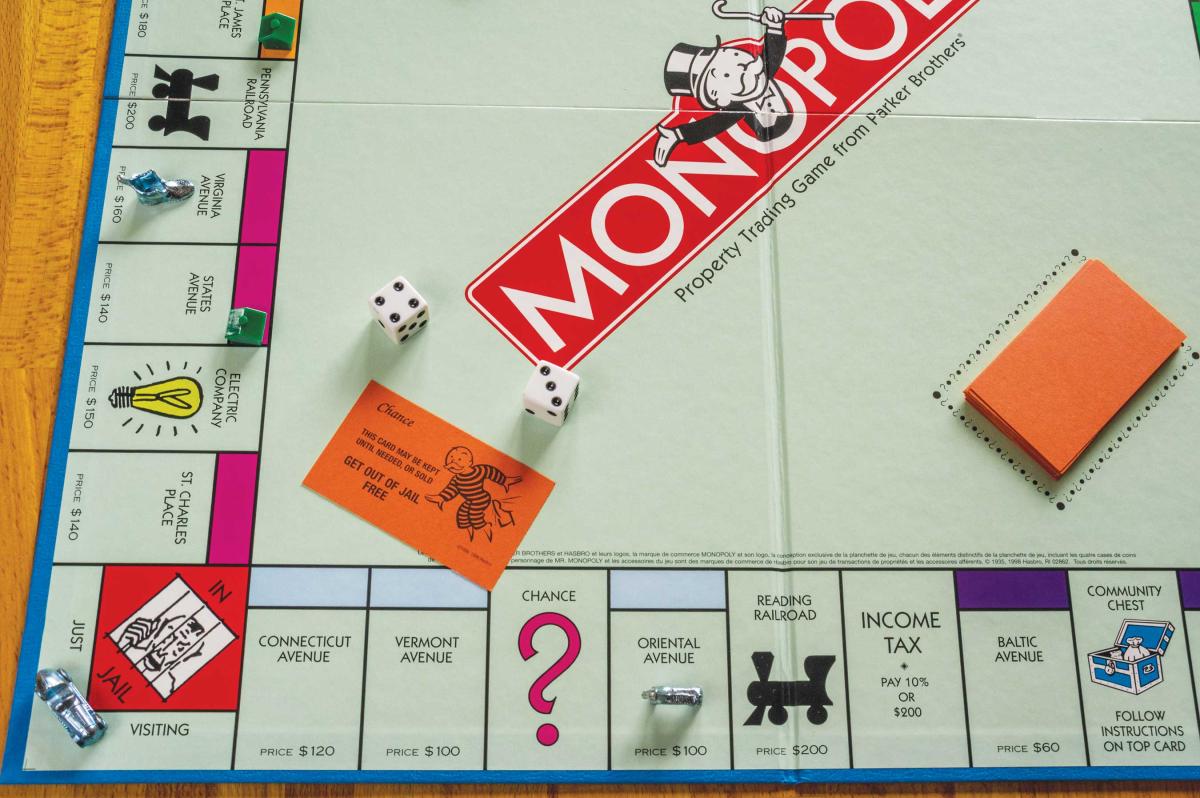

Another label states that Monopoly, which became popular in the 1930s, was first hand-crafted on a round, cloth playing surface that could be rolled up. The label does not mention that Monopoly was based largely on The Landlord’s Game, created from 1902 to 1903 by political progressive, feminist, and inventor Elizabeth Magie, and then enhanced by Charles Darrow, who copyrighted the game in 1933. Marketed by Parker Brothers, Monopoly soon became available as a board game. For more on the contentious history of this beloved American game, one need only consult the Strong’s own website or its Brian Sutton-Smith research library.

The Strong has an ideal way for visitors to enter its vast collection: The National Toy Hall of Fame. Before showing even one factory-produced, commercially available boxset, the hall confronts visitors with familiar objects that can be transformed into toys by a child’s imagination, such as sticks, sand, and blankets small enough for a kid to tie around their neck and wear as a superhero’s cape. Then, in a forty-minute stroll alongside exhibit cases displaying the all-stars of toys, even as you feel swept away by memories of favorite games, you are following the scent of what’s truly at the heart of this world: imagination and play.

Recent inductees to this hall of fame include the game Risk and American Girl Doll. Many are products of the Industrial Revolution, which brought sturdy materials into the manufacture of standards such as the rocking horse and cleared the way for relative newcomers such as toy trains that moved down a track. In 1901, the first Lionel trains started out as a holiday window display for a retailer, only later morphing into a toy.

Curator Chris Bensch provided me a behind-the-scenes tour of the collections not on view, which are kept in some instances in cold storage and in catacombs of flexible storage shelves. Many of the toys are plastic and emit gasses; storage must therefore come equipped with an exhaust apparatus for off-gassing. The Strong has received vast donations of video games from Mayfair Games cofounder Darwin Bromley and from Atari. Hundreds and thousands of these games are lodged in flexible storage awaiting the probing minds of future researchers.

How do collectors choose what to donate? Bensch admitted that some collectors have a hard time deciding, so guidelines need to be provided. He remembers one exceedingly generous offer of Smurfs. The collection was too large even for a museum of toys. For the donor, Bensch framed the problem this way: Only 125 Smurfs can go on Noah’s Ark. Which ones, out of the five thousand you are offering, are we going to select?

What is a toy? In the seventeenth century, French philosophers René Descartes and Blaise Pascal became embroiled in debates that may shed light on the surprisingly vexed question of what makes a toy a toy. Descartes viewed man as a machine, part of the cosmos, a system governed by reliable rules and constructed with unfailing precision. Clockmakers emulated this system and created, in effect, a solar system in miniature in their timepieces. “The modern toy,” wrote play and toy scholar Brian Sutton-Smith, “may be seen in part as a symbolic legatee of this first optimistic scientific view of the planned universe.”

Pascal, on the other hand, was less sanguine about this rush to control the cosmos by reducing it to springs and cogs. “The heart has its reasons,” he wrote, “which reason knows nothing of.” Mechanized toys manufactured in Germany and elsewhere in Europe at the time became the progenitors of walking-and-talking dolls and toy train sets, while the plush dolls that were created in France and elsewhere—cozying up to Pascal’s feelings—were the ancestors of dolls, cuddly and fashionable, and soft furry critters children take with them to bed. The mechanized toy for a mass market was the natural offspring of the Industrial Revolution, while the soft toy came down to us today through the luxurious dolls hand-crafted largely for the aristocracy.

During the late eighteenth century, changing attitudes toward children could be seen at home and in the toys chosen for them by parents. First in England and then in the United States, books for children, with larger type and simpler language, were published, and, in large cities, toy stores opened. In the twentieth century, many children came to have their own bedrooms, where they could spend hours playing. Postwar homes often incorporated playrooms, sometimes centrally located so parents could participate. For infants, suspended plastic balls and rings, play gyms, and mobiles filled cribs and play spaces, while train sets, Tinker Toys and Legos, dollhouses, Mouse Trap, wiffle ball, Big Wheels, and Twister awaited many children just around the corner as they grew older.

Over time, the development of toys reflected an interest in solitary pursuits that might lead to careers in industry, technology, and the sciences—a chemistry set, for example. These days, many of the old toys have changed but parental intent remains key to understanding them.

As Sutton-Smith, writing in the mid 1980s, posited in Toys as Culture, “Infant bedrooms may demonstrate a parental concern for children and a belief in their educability. They are the latest phase of the great parental ambition for the achievement of their young that first became noticeable about 200 years ago.”

Toys help create a bond between parent and child. A cuddly unicorn, rhinoceros, or collie reinforces the affection radiating from parents and provides an enduring, sometimes lifelong, source of comfort for the child. The teddy bear, thanks to stories of Theodore Roosevelt saving a black bear during a hunting trip in 1902, became the toy of choice for generations of children in the early decades of the twentieth century. The origins of Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy reach back to the same period and provide nostalgia to boot. The Cabbage Patch Doll, a phenomenon of the 1980s, also draws on a child’s basic need to comfort and be comforted. Cabbage Patch Dolls came with birth certificates and were “adopted” by their partners in play. Soft toys and dolls are especially associated with holidays when gifts are given to increase the parental bond.

Throughout history, though, toys were not designed with children specifically in mind, and it was not customary for children to play alone. Rather, children played with other children, and only rarely with adults. They made up their own narratives while playing with sticks, mud, or household, even religious, objects. It was not until clocks were invented, then, that this miniaturization of the cosmos and the growing desire for control over it led to the profusion of automated toys seen in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From toy makers in Germany came mechanized ducks that walked and quacked, while figures in crib scenes hammered and sawed.

Later on, American manufacturers constructed a vast array of mechanical banks. Parents, of course, hoped that playing with the bank would encourage saving. Many of these toys’ and banks’ manufacturers were based in the industrial northeastern United States, such as J. & E. Stevens Co. of Cromwell, Connecticut, founded in 1843, eventually becoming the leading U.S. maker of cast-iron toys. The Strong’s collection of mechanized toys includes a Li’l Abner set of musicians, “The Dogpatch 4 Band” performing “Turnip Time.” Toys or amusements such as the Li’l Abner set, though—based on the wildly popular comic strip by Al Capp and manufactured in both the United States and Japan in the late 1940s and the 1950s—are more of a novelty for looking at than a toy to be played with, and their material, tin plate, pales in comparison with the painted metal and iron of earlier toys, automated and mechanical or not.

What play is and what toys are for are complicated questions, and responses pull in many disciplines: anthropology, education, folklore, history, philosophy, psychology and child development, and sociology, to name a few. Even literature offers a perspective. D. H. Lawrence’s short story “The Rocking-Horse Winner” sheds light on the force of the imagination while playing and what transformative results for good or ill can result (mostly for ill in Lawrence’s story). From teachers, psychologists, and marketers comes the message that toys can be educational, while philosophers champion the value of wooden versus metal toys, sociologists debate the question of whether toys can be dangerous or not, and anthropologists underscore the universality of play, with or without toys.

Play, however, is an ambiguous term and many things that are called play are, actually, something else. When we see infants interacting with toys we may think they’re playing, but it’s more likely that they’re working. The toy in an infant’s hands is a tool used to discover and explore rather than to amuse and entertain. Adults, on the other hand, who create extensive miniature landscapes and towns for their train sets in the basement and collect dolls, board games, or mechanical banks are not exactly playing either. It can also be hard to say what a toy is, but if we agree to think of toys as the objects children from the ages, say, of three to twelve play with, then we at least have some common ground for thinking about play generally. That doesn’t mean, unfortunately, we know what toy is best for children to play with—yet another hotly debated question.

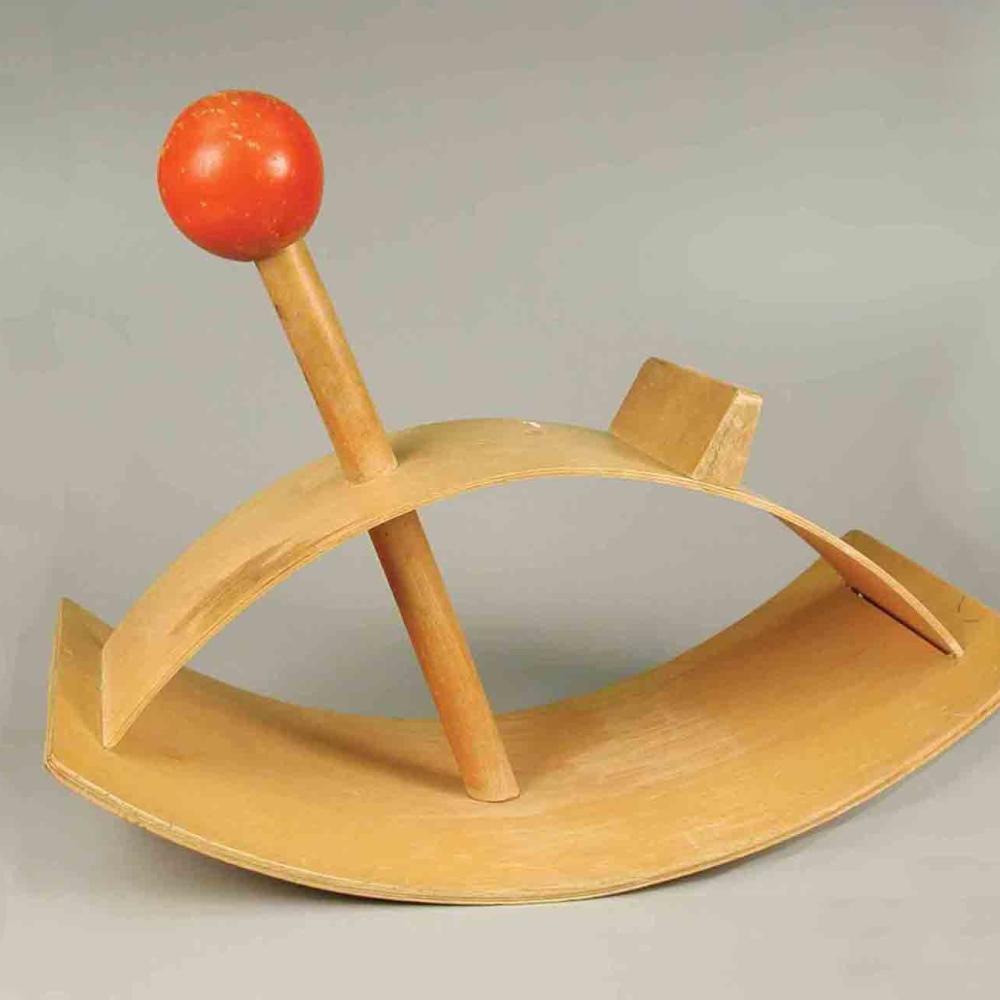

Toys that leave something to the imagination enjoy a certain vogue that goes back decades. In the early 1950s, Charles and Ray Eames designed kits of paper toys that allowed children to experiment with construction. In the same vein as toys designed by the Eameses but produced later in the 1950s by Frank and Theresa Caplan for Creative Playthings was a rocking horse with no equine detail at all but which beckoned to be ridden anyway. The clean, minimalist lines of its design and the material, smooth wood, exudes warmth, with appeal as well, it was hoped, to the imagination. Additionally, French philosopher Roland Barthes weighed in on the wood versus metal debate in what material is best in toys: “Wood removes,” he wrote, “the wounding quality of angles which are too sharp, the chemical coldness of metal. . . . It is a familiar and poetic substance.”

Technology, culture, and toys and games have become fully intertwined, nowhere more so than in video games. More than half of American adults play video games. If the dexterity and ease with which many Americans these days text and order from menus accessible only through QR codes is any indication, they must have been acquiring these abilities somewhere along the way, most likely by playing video games when they were young.

When curators and staff talk shop at the Strong, the names of the men and the women at the heart of the world of toys, games, and play are ever on the tip of the tongue, much as when baseball fans gather and trade tales about Babe Ruth, Josh Gibson, Walter Johnson, and Satchel Paige. In addition to Ralph Baer and Darwin Bromley, there are Allan Alcorn, Nolan Bushnell, and Ted Dabney, all of whom figured into Atari’s meteoric rise in the early seventies, after the first arcade version of Pong was installed in Andy Capp’s Tavern in Sunnyvale, California, in 1972. Then, too, there’s Dave Nutting, designer in 1975 of the first video arcade game to use a microprocessor, Gun Fight; Marvin Glass, designer of Mouse Trap; and the incomparable and prolific U.S. game board designer Sid Sackson, who kept journals and index cards on the games he played during his lifetime and who wrote the go-to guide for gamers, A Gamut of Games. In addition to play scholar Brian Sutton-Smith, mavens of all things playful include Vivian Paley, a preschool teacher and author who championed the importance of storytelling in early childhood development, and Johan Huizinga. It was Huizinga who, mid-century, penned the foundational work, Homo Ludens, establishing the importance of play in the creation of art and culture.

All of the above luminaries could probably agree on the importance of play in U.S. history, but a concise definition of play does not exist. We know that play is central to human development and provides, or can provide, invaluable opportunities for socializing, but it can also isolate us from each other. Moreover, Brian Sutton-Smith has warned that taking play too literally and attempting to pigeonhole the behavior of those who play runs the risk of falling irrevocably into silliness.

Toys and games may begin with sand, mud, and sticks, or they can be as complicated as the latest video game, requiring dexterity and focus. The former emphasize socializing and cooperation among groups; the latter, isolation and concentration of an individual. The tendency to design games that make us feel in control of the cosmos reaches its zenith in video games, which can often emphasize combat and violence. Former head of the Strong, George Rollie Adams has noted, however, that “research doesn’t support the claim some make that playing electronic games causes people to go out and inflict bodily harm on others.” “Play violence,” he hastens to add, “is not real violence.”

Indeed, play is more than a parody of real things. It is an activity of the mind and the body, developmentally useful, creatively important, and personally gratifying. And it may be much more than that. But at the Strong, where I stood shoulder to shoulder with hundreds of kids, witnessing firsthand their wonder and awe, their sense of curiosity and adventure, their thrills, spills, and surprises, I did not, in my heart, need more reasons than these to find play inspiring.