Claiborne Pell, U.S. senator from Rhode Island from 1961 to 1997, was a man of passionate interests and deeply held convictions. Quite remarkably, he managed to turn many of those interests and convictions into long-lasting laws and national policy during his six terms in the Senate. Early in his first term, for example, he translated his enthusiasm for train travel into legislation that created Amtrak. His love of the sea led to legislation launching a major expansion of oceanographic education and an international treaty banning undersea weapons testing. And his determination that those less financially fortunate than himself be able to afford a first-rate college education resulted in the transformative asset of Pell Grants.

Even among that list of remarkable accomplishments, Pell’s success in creating federal programs that provided significant financial support for the arts and humanities at both the national and state levels remains an enduring legacy. While his specific concept of how the humanities, and particularly the state humanities councils, should be structured and operate was often at odds with bureaucrats both national and local, he never relented in his forceful advocacy for the humanities in American life.

Coming from a Rhode Island family deeply involved in Democratic politics, I had been personally aware of Pell for much of my life. As a child, I had met him a few times before his insurgent 1960 campaign for the Senate, in which his main opponent in the Democratic primary was my uncle, Dennis J. Roberts. Pell was, as he himself put it, “about as improbable, impossible and implausible a candidate as could have turned up in many a moon.”

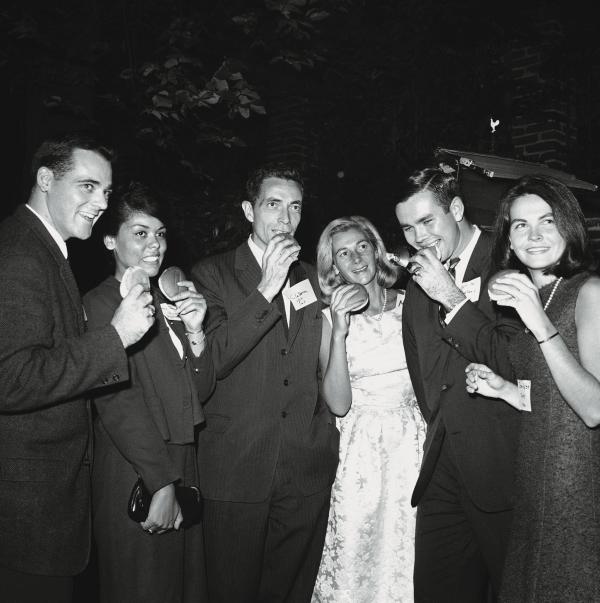

Nineteen sixty was a time of change. On the national level, John F. Kennedy became the first president born in the twentieth century. Pell was a new face in politics, whose extensive advertising campaign, especially on television, was something of an innovation at the time. It introduced a little-known Brahmin to thousands of working-class Rhode Islanders, and it worked to get him elected. Pell defeated my uncle and two others in the Democratic primary and went on to win the general election by a significant margin. After his victory, fences were mended and he became a senator dependably loyal to his Rhode Island constituents and state Democrats. He never again faced a primary challenge.

Apart from reading about him in the news, I did not encounter him again until my own engagement with NEH and its state programs began in 1972, when I was hired to help the fledgling Rhode Island council conduct its early planning activities. For the subsequent 24 years, despite differing views on some procedural matters, Pell’s regular dealings with me were always considerate and supportive. He recognized that it was my job to make his vision a compelling reality in his home state. That much we had in common. Our backgrounds and temperaments, however, were decidedly different.

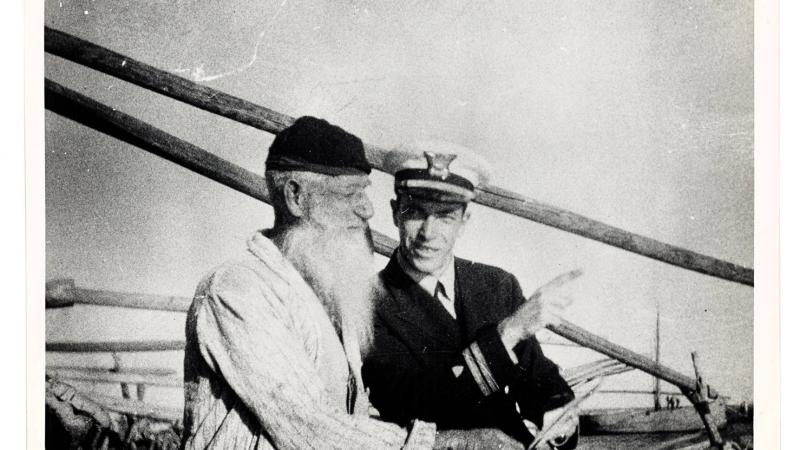

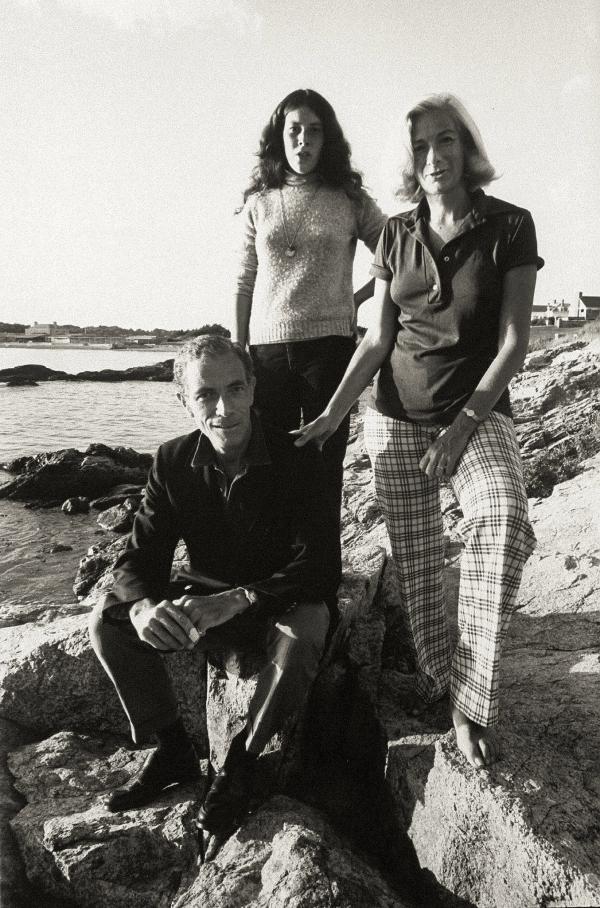

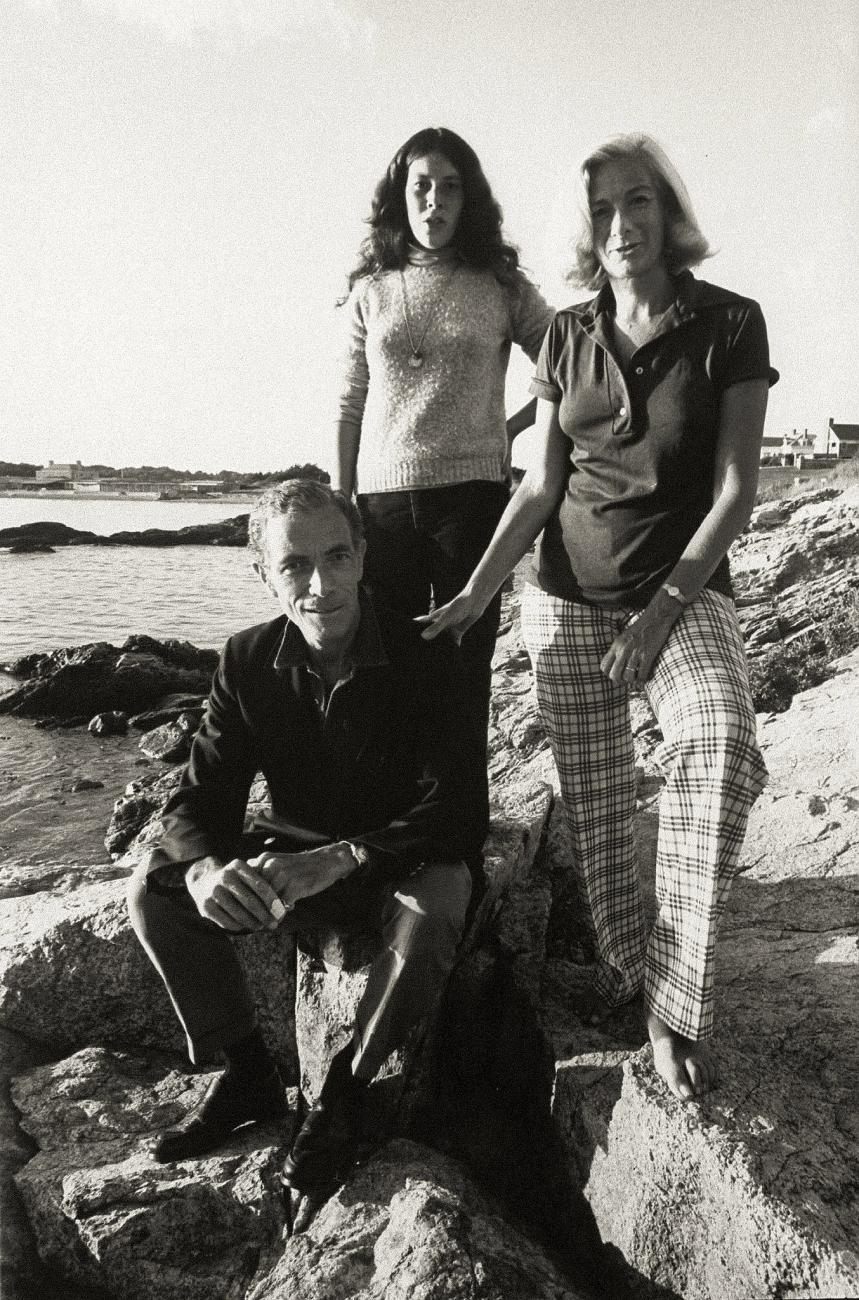

After his 1940 graduation from Princeton, Pell enlisted in the Coast Guard, in which he served throughout the Second World War. Seeking a postwar career in public service, he joined the State Department, which included Foreign Service postings in Italy and Czechoslovakia. Returning to Washington in 1950, he purchased a home in Georgetown. At the time, D.C. residents were not permitted to vote in national elections. Pell’s and his wife’s families had long-established summer residences in Newport, Rhode Island, and it was there in the early 1950s that he designed and built a modest one-story house on waterfront property that had belonged to his wife’s family. That remained his voting residence for the rest of his life.

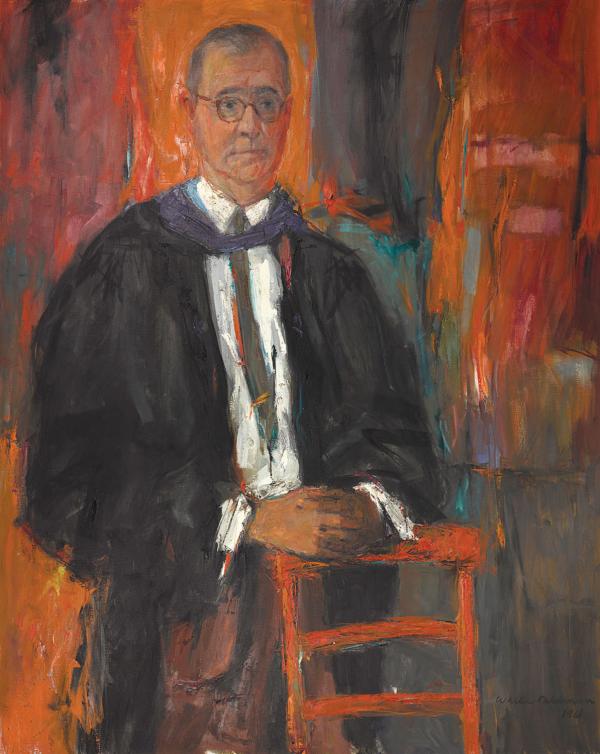

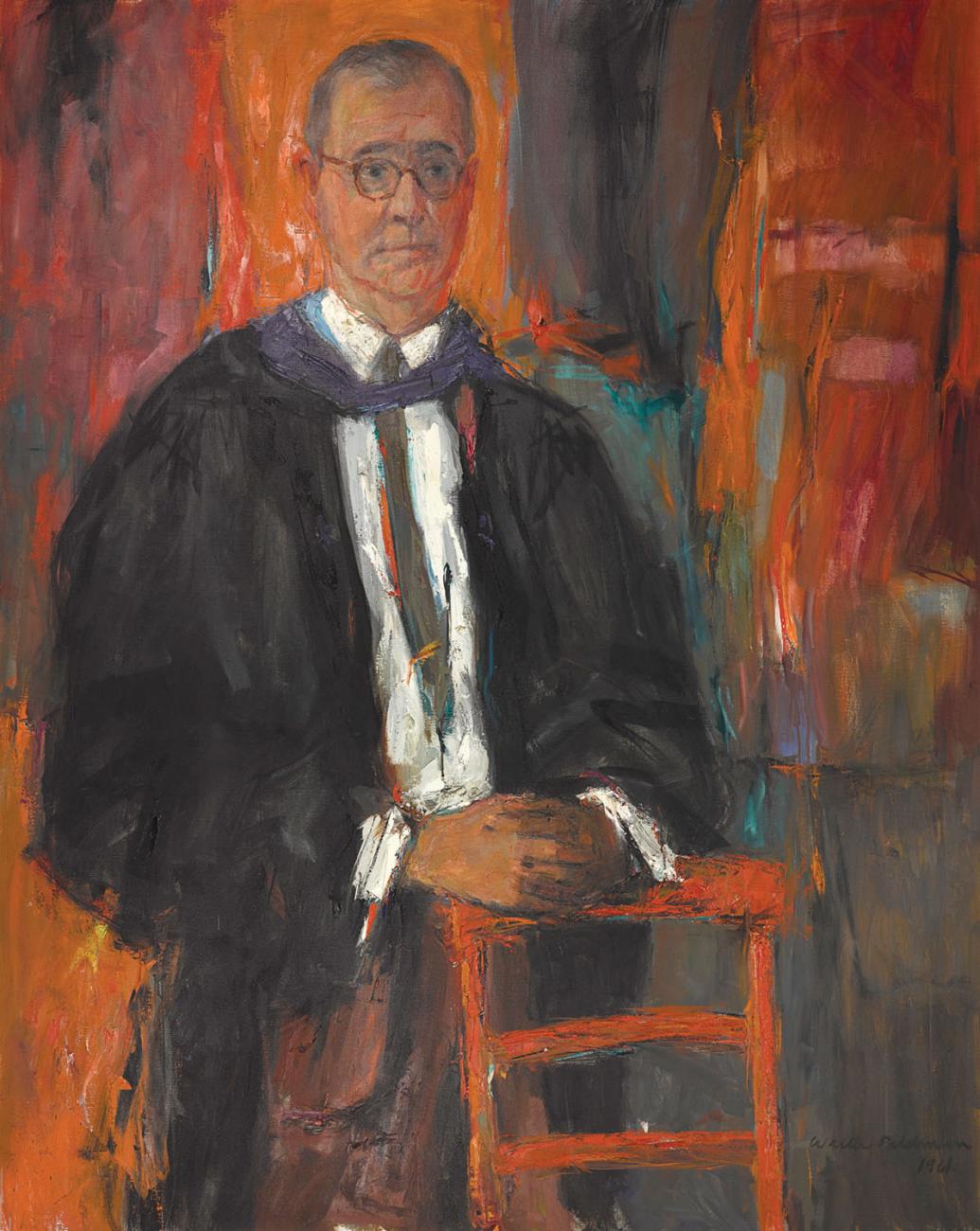

Coming from wealth and an American lineage dating to the early seventeenth century, Pell grew up in a family steeped in art and culture. His stepmother, a professional painter, and his father had amassed an impressive collection of fine art, which he inherited. It included many portraits of his own ancestors. Pell’s first term in the Senate coincided with a growing movement in the cultural world and, to an extent, in Washington for government support of the arts. President Kennedy had made performances by distinguished artists a regular occasion at the White House. And Pell’s background and interests made him well suited to a national effort to promote culture. He enthusiastically energized a small band of senators, notably including Republican Jacob Javits of New York, in promoting legislation to establish a Federal Advisory Commission for the Arts.

At this point, from Rhode Island came a voice encouraging Pell to broaden his cultural strategy. Brown University President Barnaby Keeney urged Pell to include the humanities in his legislative agenda. Keeney was then serving as volunteer chair of the just-formed NGO the National Commission on the Humanities and would later become the first chairman of NEH. Pell embraced that charge and, with support from Javits and a number of other senators and representatives as well as from President Johnson, he spurred the creation of national endowments for the arts and humanities in 1965. It was quite a coup for a first-term senator with little political experience.

From the outset, the arts endowment’s operational structure involved state arts councils, state government agencies whose funding came half from the NEA and half from their state’s budget. (Before the NEA, a handful of states—most notably New York—had been providing some form of financial support to local artists and organizations.) NEH had no such counterpart. State arts council members were appointed by governors or other state officials, and the councils supported smaller institutions and events as well as local artists. Pell found this structure to be the ideal format for how both endowments should operate. As his second term began, he used every opportunity to urge NEH to replicate the NEA state government council model. NEH resisted.

Although he spent summers in and voted in Rhode Island, Pell had never served in that or any state’s government. His brief career in the foreign service and his time at Princeton were most likely characterized by exchanges among well-educated, well-spoken, well-placed individuals, people a lot like him. The U.S. Senate at the time was much the same. His assumption that similarly cultivated people were working the corridors of power in state capitol buildings must have inspired in part his unyielding insistence on the state government model for NEH programs at the local level.

Throughout his long career, Pell deployed an arsenal of phrases and metaphors to characterize his views. His frequent success at engendering bipartisan support for his legislation he described as “letting the other fellow have my way.” His stubbornly held views on whom the two endowments should serve and who should sit on state council boards were distilled into two metaphors. Government-supported culture was, he would say, for cobblers with a passion for opera. That fanciful image may have emanated from his extensive travels in prewar Europe as a young man; in 1970s America, those cobblers were an endangered species. As for who should sit on local humanities boards, he ardently advocated they should represent the “warp and woof” of that state’s population. That phrase referred to the horizontal and vertical threads woven together on looms to fashion cloth. For nearly two centuries, the solid foundation of Rhode Island’s economy had been built on the textile industry. By the 1970s, however, textile manufacturing had moved to nonunion southern states and, ultimately, overseas. His taste for such arcane terms was a central part of Pell’s charm to both his colleagues and his constituents.

In 1971, when NEH did establish its counterpart to the state arts councils, the architect of the program, NEH Division of Public Programs director John Barcroft, carefully labeled them “state-based programs” and not “state councils.” They were to be independent entities, funded by NEH after application and review. They were grantees of NEH and the funds they in turn awarded to local organizations were “regrants.”

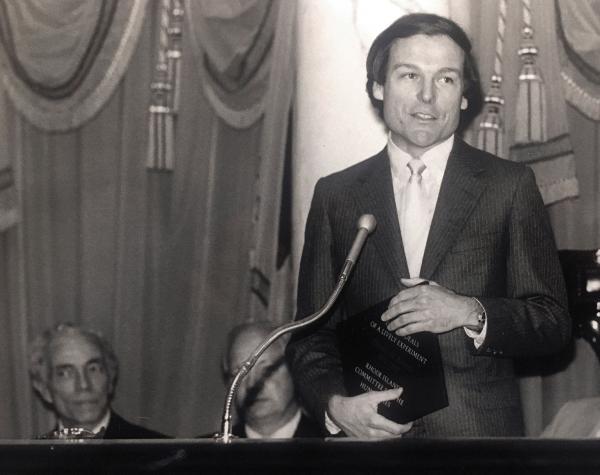

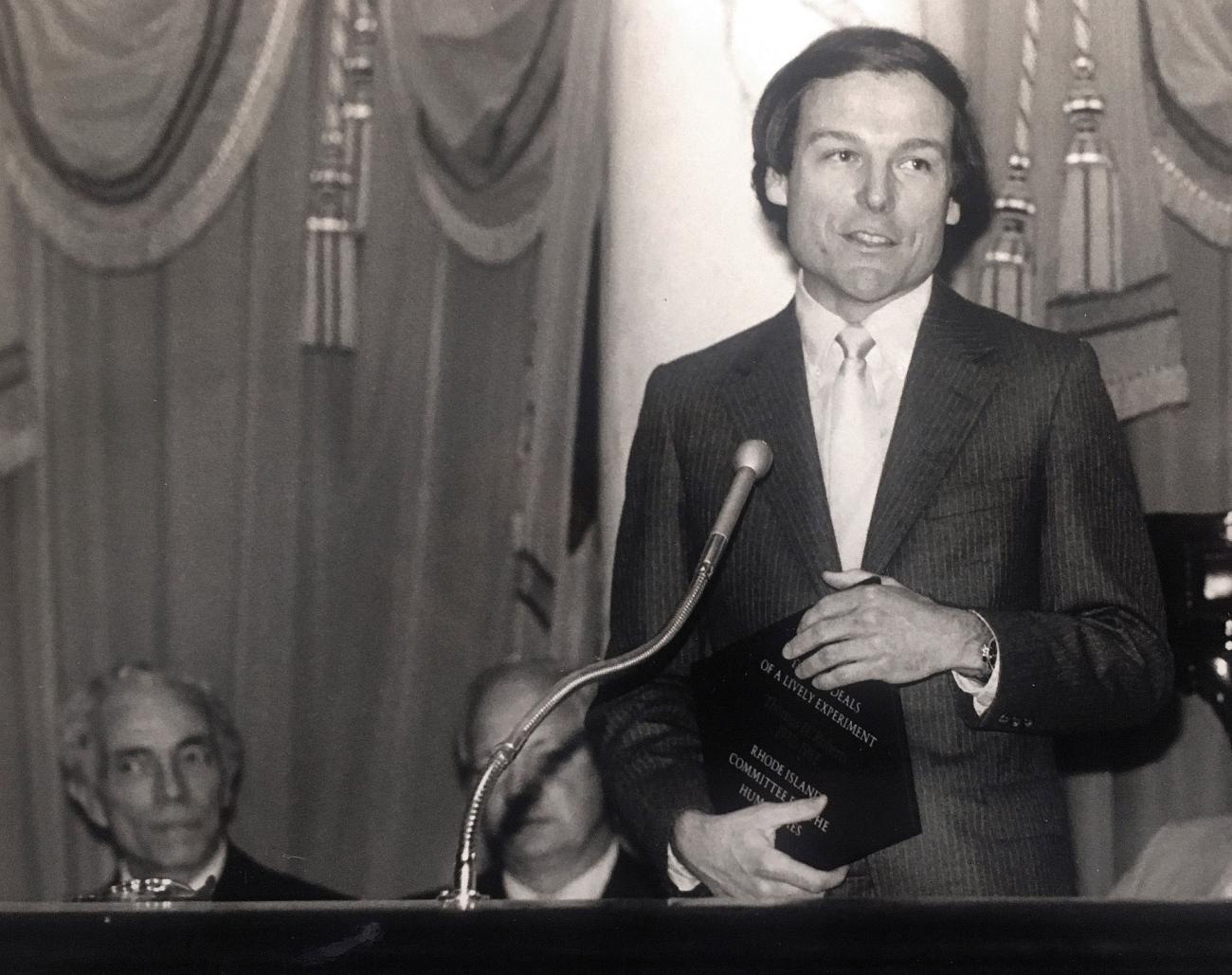

NEH selected a small group of “catalyst” members in each state who were directed to plan for a humanities council in their state and to expand their numbers from among the academic, cultural, business, and public sectors. It was at this stage that I became involved with the catalyst group in Rhode Island, helping to organize their planning activities and writing the report on their findings, a report that was simultaneously an application for approval as the accredited NEH state-based program. When the Rhode Island Committee for the Humanities became operational in 1973, I was named its first executive director. I stayed for 23 years.

There was clearly some sensitivity at the endowment about how the program would unfold in Pell’s home state since the senator had already expressed misgivings about how the NEH state model differed from that of the NEA. In designing the state-based programs, Barcroft had determined that the subject matter of all their regrant activities would be public policy issues such as civil rights, reproductive rights, the environment, violent crime, all examined through the lens of humanities disciplines. Additionally, every state program was required to develop a theme under which all their regrant activities would be gathered. NEH Chairman Ronald Berman, a Nixon appointee, backed Barcroft on these guidelines.

None of these structural elements pleased Pell. While he had resolutely pressed for supporting the humanities at the state level, Barcroft’s vision was far from Pell’s. Pell decried the independence from state government, the public policy focus, and the self-selecting boards, which he ironically considered elitist. Because both endowments were required then to be reauthorized by Congress every two years, Pell had the legislative power to impose his version of the programs on NEH.

In the lead-up to the 1976 reauthorization, NEH and the state councils pushed back. By now five years old, the state councils had established a sizable body of supporters within most states. Those citizen allies, who came close to embodying the “warp and woof” of Pell’s vision, made their opinions known to other members of the Senate subcommittee. Pell held firm to his preferences, and his tenacity over several reauthorization cycles gradually reduced or eliminated most of the aspects that troubled him. The public policy requirement was retired, and each council was obligated to include a small number of gubernatorial appointments as board members. Despite his continued efforts, Pell never succeeded in compelling the councils to become state government agencies. He did, however, prevail in blocking the renomination of Berman as NEH chairman.

As he advanced in Senate seniority, ultimately becoming chair of the Foreign Relations Committee, Pell’s interests and involvements broadened and his laser focus on NEH and the state councils diminished but never disappeared. The councils themselves continued to thrive and expand their influence in their own states and beyond. While NEH remained the principal source of every council’s financial support, many succeeded in procuring generous support from individuals, businesses, unions, foundations, and even, not infrequently, from state governments. I left the Rhode Island council in 1995 just a few weeks before Pell announced that he would not be running for a seventh term the following year.

While his views were often at odds with those of the people who shaped and managed the state humanities councils, his unrelenting attention to the councils and the two endowments unquestionably helped assure their continued existence and fiscal health during the 30 years of his oversight and in the 25 years since he left office. It was my good fortune to know him, to work with him, to admire him, and occasionally to argue with him during the memorable years of his enormous influence. Claiborne Pell was a singular, often enigmatic man whose imprint on our cultural life will long endure.