When Lyman Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published in 1900, it was more than just a beautifully illustrated and best-selling children’s book—it would come to be known as America’s first great fairy tale. After a failed venture on the American frontier, Baum used his fertile imagination to turn his time in the drought-ridden Great Plains into a new, defiantly American literature for children.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, books written for children were instructional and sermonizing. They sought to impart moral and religious values. The most popular fantasy stories for children came from Europe, such as the tales of Hans Christian Andersen, Brothers Grimm, and Charles Perrault. Baum’s book offered otherworldly adventures firmly rooted in the American landscape: In this case, Kansas, with a plucky, self-reliant girl who doesn’t need a prince to save her, a sunny appreciation of hucksterism, and good witches.

“There is a real American value of being self-reliant, and you see that with Dorothy,” says Dina Massachi in American Oz, a new American Experience documentary airing on PBS on April 19. “Dorothy really set the stage for little girls getting out of the house and going on adventures the way that boys do.” Gregory Maguire, author of Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, adds: “Dorothy goes into a land in which magic spells are part of the apparatus of governance. And most of what she achieves she achieves without recourse to the magic. She comes with her true grit. She just puts one foot in front of another along the Yellow Brick Road to achieve what it is that she needs to do.”

Living on the cusp of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Baum embraced new American ideals of innovation, imagination, and the courage to leave your home for something magical in another land. And when that failed, and it often did for Baum, he used those qualities to reinvent himself, again and again.

Born in 1856, Baum enjoyed an idyllic childhood on the outskirts of Syracuse, New York. But his heart was not in the family oil business. At nineteen, a restless Frank left home to ride the wave of a new craze, fancy chicken breeding. This was the first in a long line of short-lived stints with varying degrees of success—traveling actor, singer, playwright, and axle grease salesman, all bankrolled by his family.

While an actor, he met and married Maud Gage, the daughter of Matilda Joslyn Gage, a nationally known activist who cofounded the National Woman Suffrage Association with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Matilda was none too happy about her prospective son-in-law, but an equally strong-willed Maud persisted. Frank and Maud married in a simple ceremony held in the Gage’s parlor. Their vows were so unusual for the time that they were reported by the local newspaper: “The promises of the bride were precisely the same as those required of the groom.”

In 1886, Baum and his family moved to Aberdeen, a booming frontier town in the Dakota Territory, what is now South Dakota, where Maud had family. Baum wrote to his brother-in-law, “In your country, there is an opportunity to be somebody.”

Like most fortune-seekers of the era, Baum came by rail, not in a covered wagon. Less than two weeks after arriving, he opened Baum’s Bazaar, a novelty store stocked with exotic goods, fancy china, toys, books, hobby supplies, and other non-essentials. He promoted the business with clever advertising. Nearly a thousand people showed up for the grand opening, enticed with “a box of chocolates, shipped in from Chicago, for every lady attending.” The Aberdeen Daily News reported, “Mr. Baum has demonstrated in a very short time that he possesses to an enviable degree the push and enterprise necessary to the western businessman.”

After a year in business, Baum encouraged other business leaders to field a professional baseball team. The town built a grandstand to seat five hundred spectators. Baum’s Bazaar, of course, supplied the uniforms, bats, and gloves. Life was good for the Baums. Business was good and Maud enjoyed living near family, and her mother frequently visited, staying with the Baums for months at a time.

Then the drought came and the Baums’ American dream in the West turned to a nightmare. Crops turned to dust. With farmers struggling to feed their families, there was no need for toys or hobbies. With some money left over after the store’s foreclosure, Baum started The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, and worked to set it apart from the town’s eight other papers. He often wrote articles to encourage women’s rights. “We must do away with sex prejudice and render equal distinction and reward to brains and ability,” Baum argued, “no matter whether found in man or woman.” He also implored the citizens of Aberdeen to vote for women’s suffrage. “This great question, involving the political future of our wives, mothers, sisters and daughters will be decided for South Dakota next Tuesday. The enfranchisement of one-half of the citizens of this great state is in your hands.”

As the drought and foreclosures continued, women’s suffrage failed and so did Baum’s ventures in the West. Looking for a new start, the Baums packed up their four sons and moved to Chicago, a dynamic city that reinvented itself after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, growing by 600,000 people in 1890 alone. When the Baums arrived, the city was abuzz with the planning and construction of the World’s Columbian Exposition to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s landing in the New World. Over the next six months, the Baums were among 27 million who attended, including two wizards of electricity, Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla.

The central hub of the Exposition was the White City, featuring a glimmering manmade lake, surrounded by fourteen “great buildings” of monumental proportion designed by prominent architects. All the buildings were temporary structures, constructed of plaster, not stone, painted white and illuminated with nearly 100,000 incandescent lamps, demonstrating how electricity would forever change the world. Historian Philip Deloria says, “One of the things that happens in the Emerald City is the realization that all of this may just be a charade. The world that seems so alluring, and so true, and so desirous may all just be a fraud. And the White City gives us that as well.”

During this time, Baum scraped out a living as a traveling salesman. He also tried submitting short stories and poems to magazines, writing contests, local newspapers, and publishers with little success. At home, he spun elaborate stories to entertain his young sons. After overhearing one of the stories, Gage, a published author, encouraged him to pursue writing children’s stories.

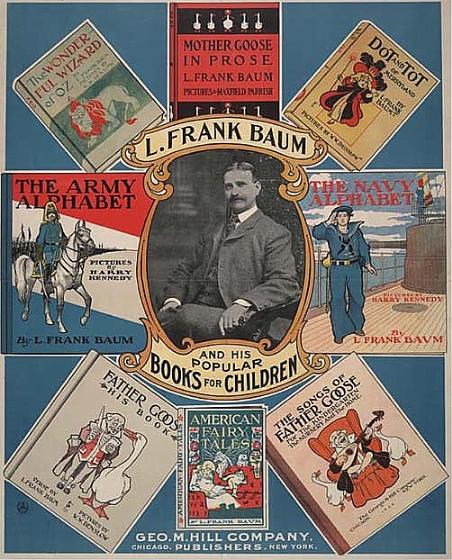

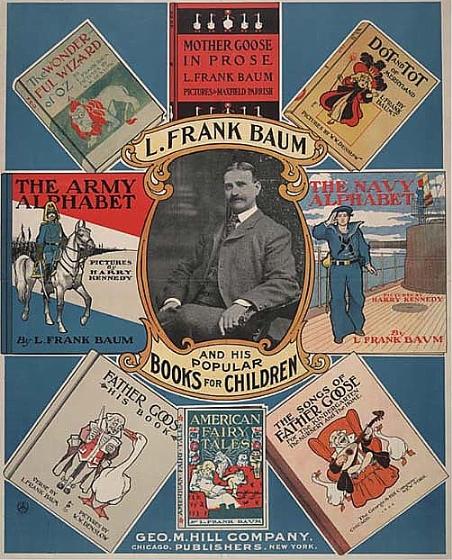

After publishing his first story, Mother Goose in Prose, Baum met William Wallace Denslow, a highly regarded Chicago illustrator. Their first collaboration, Father Goose, His Book, became an unexpected best-seller. Energized, Baum felt it was time for a new type of fairy tale, reasoning that teaching morality is not the job of stories. In the introduction to Oz, he writes, “Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident. Having this thought in mind, the story of ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’ was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.”

Gage was a role model for some of Baum’s famous characters. In her feminist treatise of 1893, Woman, Church and State, Gage wrote about how society has witches all wrong. She said, “The witch was in reality the profoundest thinker, the most advanced scientist of those ages.” Baum transferred this into his tales. In Oz, when Dorothy first meets the Witch of the North she says, “I thought all witches were wicked.” “Oh, no, that is a great mistake,” replies the Witch of the North.

“The phrase ‘good witch’ doesn’t really come into the culture until L. Frank Baum,” says Maguire. “Witches from European and English fairy tales were old, and gnarled. How brave and thoughtful it was of Baum to take those two words that seemed to have magnetic pulls in opposite directions, the word ‘good’ and the word ‘witch’ and to hinge them together so that they could mean something new.”

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz succeeded in breaking the fairy tale mold. “He did not see gender the way a lot of people of his time saw gender,” says Massachi. “His supporting Scarecrow, Tin Man, Lion didn’t conform to this typical male role. You have the Tin Woodman, who is so sensitive that he cries when he steps on a beetle.” Maguire says, “What he did in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was harness his great idea of a child going out and coming back home in strict, plain, American prose. He let the characters move about the landscape and speak with a sincerity with which America was then known and for which it was often much mocked. But it was a genuine tone. That what you say means something.”

Baum was familiar with Kansas, his setting for Dorothy’s home. The Baums had been there early in their marriage, while touring with his original play, The Maid of Arran. Maud described the landscape as “the grimmest place I have ever seen.” Baum’s Oz tale is not necessarily an appealing portrait of American life—the parched gray Kansas plains, a worried and joyless Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, cyclones, a leader who is all show and no substance—yet it’s a story of how magic can be found in even the harshest environments.

The book was an instant success, with fans begging for more. Baum used his great imagination and skills to turn Oz into a brand with varying degrees of success. He wrote thirteen more Oz books, and several stage productions went to Broadway and on tour. Baum produced the Oz-based Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, a multimedia show in which Baum narrated and interacted with the characters from Oz. A silent film was even made of The Patchwork Girl of Oz, the seventh book of the series. In 1910, Frank and Maud moved to Hollywood and lived in a comfortable home they called Ozcot.

In 1939, twenty years after Baum’s death, MGM’s iconic movie in Technicolor premiered with Maud in attendance. “One of the greatest thrills of my life will be to see the land of Oz . . . come to life under the magic of MGM,” she said. The Wizard of Oz won two Academy awards, and Judy Garland was given an honorary juvenile award for her portrayal of the story’s heroine, Dorothy Gale. It lost the best picture category that year to Gone with the Wind. In 1959, CBS began its annual broadcast, with more than 45 million people tuning in. This shared national event became a tradition for American households, running yearly for more than three decades. It helped established Baum’s story as a great American icon, one that is distinctly American, firmly rooted in American soil.

“Imagination,” Baum wrote, “transforms the commonplace into the great and creates the new out of the old.”