In recent years, artists and creators in Muslim societies have been drawn to graphic narratives as a platform for speaking against social and political injustice. The form itself is subversive, blending text and image—an inherently risky balance, considering the Islamic doctrine of aniconism, which prohibits the pictorial representation of objects as well as the illustration of God and the Prophet.

As a literary scholar interested in comics, I am especially interested in works that pluralize and humanize Muslims by showing their everyday struggles in challenging environments: in contested territories such as Kashmir or Palestine, in uprisings during the Arab Spring in Egypt, or amid protests against civil rights violations in theocratic states such as Iran.

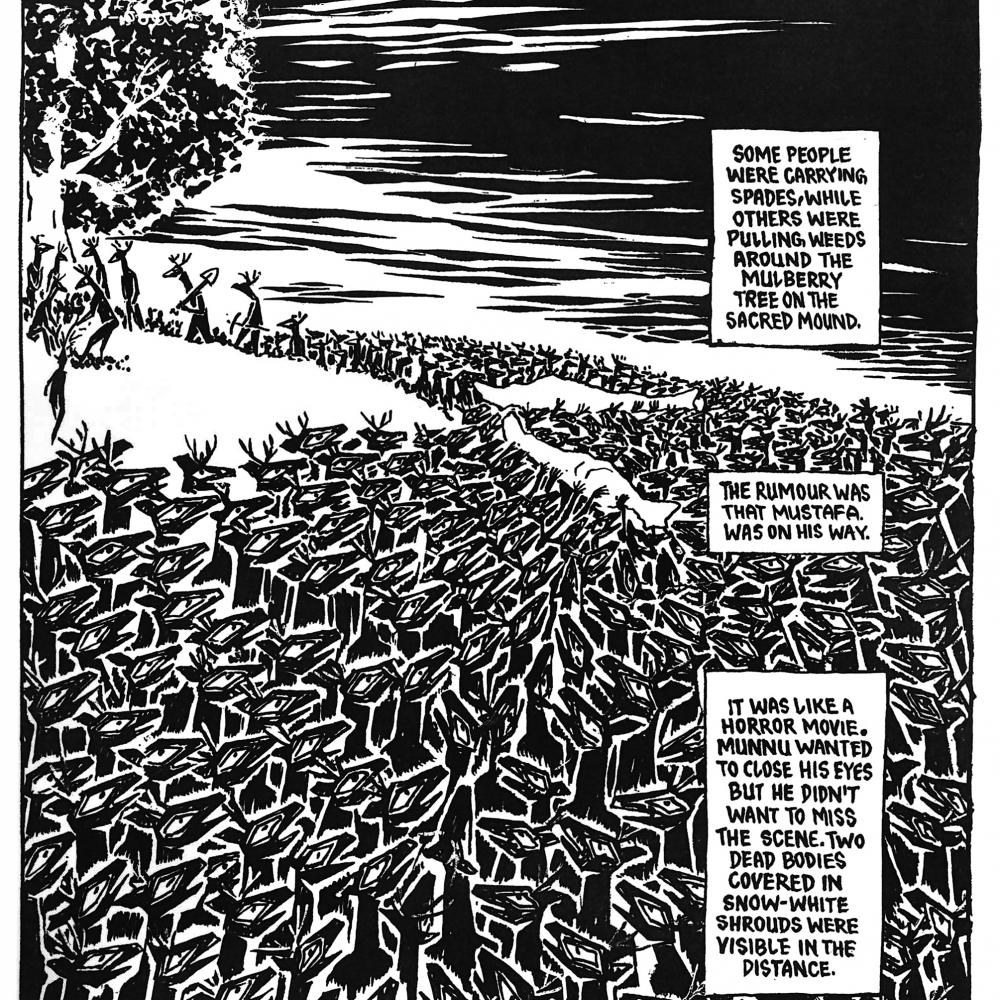

Malik Sajad’s Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir, for example, offers a coming-of-age story of a Muslim protagonist, growing up in Indian-occupied Srinagar alongside a growing number of Pakistani-backed insurgents. The panel featured here shows a funeral procession for Mustafa, an alleged member of the freedom movement.

Employing a “visual grammar” that echoes Art Spiegelman’s anthropomorphic use of animals in Maus, Sajad illustrates Kashmiris as hanguls, an endangered species of deer. By emphasizing the vulnerability of the Kashmiris, Sajad delivers a critique of the random crackdowns, illegal detentions, and extrajudicial killings of a hegemonic state. The hanguls, in this sense, visually reinforce the idea of dehumanization experienced by those excluded from traditional human rights.

The highly stylized layout illustrates the mythologizing power of religion. Sajad is aware of local efforts to link the Kashmiri freedom movement with jihad. And even though he is overtly critical of politicized religion, his depiction of this funeral shows how religion and politics are in many ways natural partners. In death, Mustafa becomes a martyr and joins the cult of the shahid—a “witness” who sacrifices his life for the greater good of Islam. As the mourners convey his shrouded body from shoulder to shoulder, they pay their respects for the fallen hero before laying him down under a mulberry tree, where, we are told, “the descendent of the prophet Muhammad was buried.” The mourners look up, imagining their new martyr ascending, and the image brings readers into the act, drawing them irresistibly upward, as if looking to heaven. As much as Sajad attempts to show the futility of these deaths, he cannot deny the visual spectacle, nor the power of witnessing as a collective performance of solidarity.

Sajad’s graphic narrative creates a complex artistic statement designed to counter streamlined official histories while simultaneously criticizing the West’s indifference toward those whose rights are suspended under repressive regimes. Sajad ultimately suggests that in situations where there is no culpability or accountability for the loss of human life, and where violations of individual rights are met with apathy, we, as readers, run the risk of shedding our humanity altogether.