In the summer of 2018, fifteen veterans in Watertown, New York, turned to the humanities to help them make sense of their military experiences. In an NEH-supported program at Jefferson Community College, under the guidance of humanities professors, they examined literature and art from and about the Civil War and the Vietnam War. Then they thought about their own experiences in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other hot spots, in light of what others had thought and said about war. And, in one memorable exercise in an art studio, they created face masks.

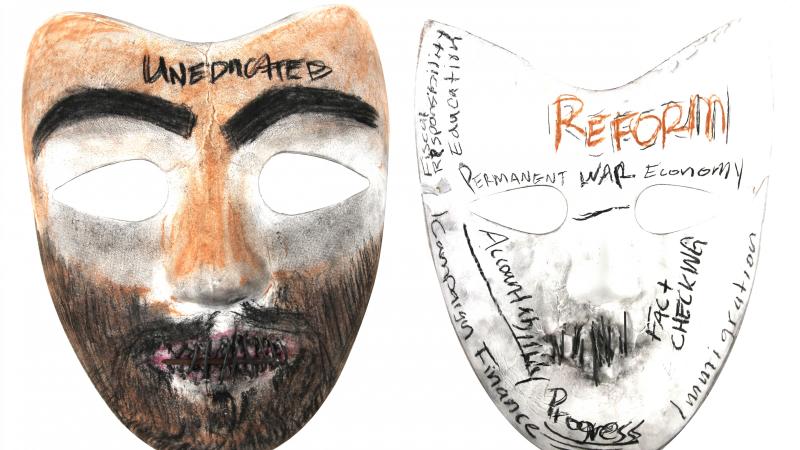

The masks were a kind of self-portrait, with one side showing the veterans as they saw themselves and the other showing how they were perceived by others. The assignment was not complicated, but the masks were striking. The veterans were asked to leave the masks behind so their professors could look for ways to share them with other audiences.

Within months, the masks were featured in an article in Humanities magazine. Not long after, in 2019, their images were used in a presentation about the veterans program to members of Congress by the National Humanities Alliance. And this year, seven of the masks were chosen by the U.S. Department of State to be part of a temporary exhibit titled “And Yet We Rise: 20 Years Remembrance and Reflection of September 11th.”

Running from September 2021 through early March 2022 at the U.S. Embassy in London, the exhibit also features the United States flag that hung at the exit terminal of Flight 93 at Newark Airport, a variety of objects left on the steps of the U.S. Embassy in London on 9/11 and the days following, and a large “Flag of Remembrance,” with names and faces of 9/11 victims, along with photographs of uniformed first responders and civilians.

For the “students who fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, 9/11 was a call to duty,” said history professor Ronald Palmer, who directed the NEH Dialogues on the Experience of War program at Jefferson Community College. “They now have a chance through their masks to engage in dialogs on war and its aftermath.”

Jefferson Community College is just 15 miles away from Fort Drum, the home of the 10th Mountain Division, a light infantry unit that is one of the most deployed in the nation. Veterans, active-duty personnel, and family members account for more than 40 percent of its enrollment. The school is one of 35 colleges and universities that have hosted NEH Dialogues on the Experience of War programs for the benefit of veterans.

“It’s always been so important that we listen to their voices,” said Palmer, who noted that for some of the participants in the program, this was the first time they engaged with the humanities. “Being asked to share our students’ work in this 9/11 remembrance exhibit is truly an honor.”

Fund-raising efforts are under way at the college to raise money to pay for the travel expenses to send the seven veterans to London and give them the opportunity to see their masks on display at the U.S. Embassy.

The art project, called the “inside/outside” masks, gave these veterans the opportunity to explore and express their feelings about their time in the service. An array of paint colors—or just one—could be used to represent their emotions. Items such as nails, nuts, bolts and screws were also available to be attached to the masks.

“The outside of the masks represented how they thought others perceived them, or how they wanted others to see them on the outside,” said art professor Lucinda Barbour. “The inside represented what they really were feeling, or how they perceived themselves.”

For veteran Stephanie Eriacho, creating a face mask was “the best way to express how I felt,” she said. “When I started painting, all my thoughts and feeling poured into the mask.”

At age twenty, Eriacho joined the United States Navy at her father’s insistence. She was living with her Native American family on the federally recognized Zuni tribe reservation in New Mexico. Her father believed the military would give her the opportunity to see the world outside of the reservation.

Eriacho began a career as a military aircraft mechanic, a path that took her to war-torn Iraq and Afghanistan, among other deployments, and earned her numerous promotions, medals, and honors.

On the outside of her mask, Eriacho painted “just another a pretty face,” or what she believed people saw when they met her for the first time, unaware of how hard she had to work to succeed in the male-dominated field of aircraft repair.

“Inside that mask, I showed what I was actually doing in the military.” She attached washers and screws, symbolizing her work as a mechanic, and painted the inside black to show the frustration she felt when people did not recognize her competence and leadership.

In 2019, Eriacho traveled to Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., along with Palmer, Ty A. Stone, president of Jefferson Community College, and Craig McNamara, former educational coordinator for veteran services, to attend the National Humanities Alliance briefing. There, Eriacho testified before a U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee about her experience in the program.

Veteran Darren LeMorta painted the outside of his mask to resemble an American flag, the very image of a patriotic soldier. He still felt that strong sense of patriotism after 21 years with the U.S. Army. But the inside of his mask was painted black, with the names of his friends who lost their lives fighting with him in Iraq.

Christopher James (C. J.) Villanueva had painted a harsh-looking face on the outside of his mask, using nails for teeth and writing the word “uneducated” across the forehead. “That’s how people perceived me,” he said while working on the project, “but that doesn’t represent who I am.” A Hispanic man and a native of Texas, Villanueva had worked as a farm laborer before entering the military.

“There’s a certain level of racism that’s accepted in this country, but it’s hidden,” Villanueva said. He believed that his ethnic background, combined with his work as a farm laborer, lead others to believe he was not well educated.

But after serving in the military and starting at Jefferson Community College, Villanueva found a way to formally educate himself about the topics that most interested him: history and politics. On the inside of his mask, he painted the words “permanent war economy,” “immigration,” and “campaign finance.”

“Jefferson’s Dialogues on War course has made a significant impact and lasting impression on both our students and our faculty,” said JCC president Stone. “Now the world gets to see and appreciate a visual representation of the personal sacrifice made by our military, through service to our country.”

The exhibit “is such a meaningful honor for our students and it is humbling for Jefferson Community College to be a part of the experience,” she added.