One of the many legends about the Titanic involves Henry Elkins Widener, a twenty-seven-year-old bibliophile who perished when the ocean liner sank in the Atlantic in 1912.

Widener had bought a rare edition of Englishman Francis Bacon’s essays while in London, and, as one version of the story goes, he kept the vintage volume in his pocket as the ship went down, declaring, “Little Bacon goes with me.”

It’s an apocryphal tale, perhaps, one rooted in the young and wealthy Widener’s celebrated passion for the written word. Harvard’s Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library is named in his honor, and the more than 3,000 books he acquired in his short life are part of its collection.

What gives the story of Widener’s last moments a distinct whiff of antiquity, though, is the notion that anyone in his dying hour would be cherishing the essays of Francis Bacon, who first published them in 1597.

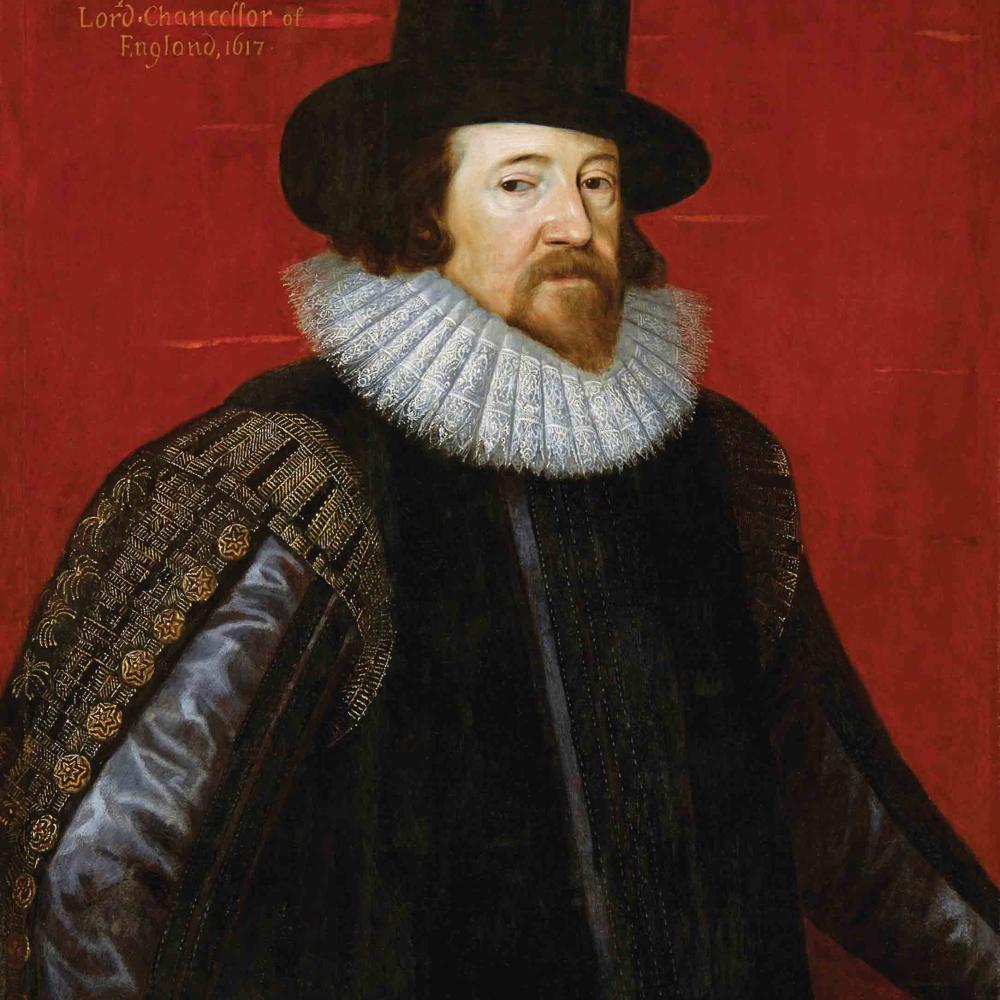

The writings of Bacon (1561–1626), an Elizabethan philosopher, statesman, and pioneer of science, are still in print, but one gathers that they’re not read very much these days. In assessing the relative obscurity of another English writer, the nineteenth-century essayist Charles Lamb, author Anne Fadiman made an observation that could just as easily apply to Bacon: “It is a bad sign when a writer can be found more easily in secondhand bookstores—which, as I need hardly point out, are filled with books that people have gotten rid of—than in Barnes and Noble.”

Bacon’s oeuvre has, indeed, become a fixture of used bookstores, as I’ve learned in picking up a few old editions of his essays among their dusty shelves over the years. Those tattered volumes offer a few clues about the rise and fall of Bacon’s popular reputation.

“There is probably no book in all the world’s treasury of literature, which says so much in so small a compass,” author William Henry Hudson writes in introducing a 1901 edition of Bacon’s essays. Bacon did, in fact, have a genius for quickly getting to the point. His essays, which treat topics that include truth, death, adversity, empire, youth, and anger, seldom bother with clearing their throats before proclaiming their message. Here’s how he opens his essay on revenge: “Revenge is a kind of wild justice, which the more man’s nature runs to, the more law ought to weed it out; for as for the first wrong, it doth but offend the law, but the revenge of that wrong, putteth the law out of office.”

It’s vintage Bacon, touched by a temptation to swiftly reduce the vast human pageant of emotions and impulses to a general formula. He’s like Machiavelli in this way—sharply incisive but also a little bloodless.

Bacon seemed comfortable with this often ruthlessly pragmatic worldview. “We are much beholden to [Machiavelli] and others, that write what men do, and not what they ought to do,” he once observed.

What one misses, in the dry certitude of Bacon’s prose, is a sense of life gradually being worked out on the page, which is what so many of us look for in a good essay.

That ideal of the essay—the word itself translates from the French as “trial” or “attempt”—was popularized by Bacon’s contemporary, the Frenchman Michel de Montaigne, who’s widely credited with inventing the essay as we now know it.

Bacon knew of Montaigne (1522–1592), though not as well as Bacon’s older brother Anthony, who became friends with him during a government mission to France in the final years of Montaigne’s life. By that time, Montaigne’s essays had made him a literary celebrity. Novelist Daphne du Maurier thought that Francis Bacon was envious of Montaigne. She wondered “what unacknowledged jealousy lingered through the years for Anthony’s friendship with Montaigne.” As Bacon worked on his essays, he promised Anthony that they would rival Montaigne’s.

Du Maurier’s interest in Bacon is an intriguing part of his legacy. By the time she died at eighty-one in 1989, the English author had achieved international fame for darkly moody novels of family intrigue such as Rebecca and My Cousin Rachel. Though not as well known for literary scholarship, she nevertheless tackled two nonfiction studies of Bacon and his times, no doubt drawn to a life touched by enough angst to match any of her fictional characters.

In his own writing, Bacon offered few personal details. That’s probably why, centuries later, Montaigne is the essayist who’s having a cultural moment, with popular studies by Sarah Bakewell and Saul Frampton, along with freshly curated editions of his essays, attesting to his continuing appeal.

Chatty, discursive, and deeply confessional, Montaigne easily speaks to our let-it-all-hang-out standards of discourse. Whether he’s laughing at his lack of height, grieving the loss of his best friend, or musing on the family feline, Montaigne is a master at enlisting the reader as his confidante.

Bacon, by contrast, exemplifies a writerly reticence that seems to have had its zenith at just about the time Widener and Hudson grew to manhood.

“While Montaigne ranged the world, indulging all curiosities, mixing garrulously with everyone, Bacon kept to the narrow path,” Virginia Woolf perceptively pointed out. As Woolf also suggested, the aristocratic Bacon didn’t much care for the common touch that helps build a wide audience. With their regal air, the titles of his essays “enumerate the proper topics,” Woolf told readers. “‘Of Truth. Of Death. Of Unity in religion. Of Revenge. Of Simulation and Dissimulation.’ These were the subjects that the rulers discussed at their high tables. . . . He lives entirely in the world of great spirits and great business. The common people is contemptible.”

If Bacon doesn’t seem much inclined to small talk in his essays, it’s perhaps because he was the quintessential man in a hurry.

Bacon’s father, Sir Nicholas Bacon, was Lord Keeper of the Great Seal and Lord High Chancellor for Queen Elizabeth I. But after the elder Bacon died in 1579, Francis had to make his own way.

“His eminent connections were less helpful than one might expect,” literary scholar Gordon S. Haight observed in introducing a 1942 edition of Bacon’s essays. “As the eighth child, he received nothing from his father’s estate.” Bacon studied law and elbowed his way into politics, finding an ally in the Earl of Essex. But after Essex fell out of favor with Elizabeth and was arrested for scheming against her, Bacon helped prosecute his former patron, which critics found dishonorable.

After Elizabeth’s death in 1603, Bacon’s star quickly rose under her successor, King James. Bacon eventually became Lord High Chancellor, his eloquence helping to advance his rise. “No man,” wrote a contemporary, poet Ben Jonson, “ever spake more neatly . . . more weightily, or suffered less emptiness, less idleness, in what he uttered. . . . His hearers could not cough, or look aside from him without loss.”

A striking feature of Bacon’s essays—and an abiding complication—is their rhetorical ambition. Bacon’s gift for the bon mot has made him a fixture in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, where he gets several pages. Here’s a sampling:

“Knowledge is power.”

“If a man will begin with certainties, he shall end in doubts; but if he will be content to begin with doubts he shall end in certainties.”

“They are ill discoverers that think there is no land, when they can see nothing but sea.”

“Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed.”

Bacon’s writings come heavily freighted with such aphorisms, which he presumably honed in the halls of power where he frequently rose to speak. While memorable for their potency, his observations can often sound more suited to the podium than the page. One frequently gets the sense that Bacon is speaking at you, among legions in an audience, not with you, as an intimate reader. He greets us in his books as a politician rather than a friend.

Bacon also coined a proverb that seems an apt description of his political career: “The monuments of wit survive the monuments of power.” He knew a thing or two about the vagaries of power, perhaps assuming that he would be remembered more for his literary than his government career. His political fall from grace came swiftly in 1621, when he was accused of taking bribes. He eventually pled guilty and was banished from public service.

John Gribbin, writing about the case in his 2007 book about Bacon, notes that it was common in Bacon’s time and place for government leaders to accept money or gifts from people they dealt with on official business. Gribbin, along with others, argues that Bacon might have been singled out for prosecution because rivals wanted him gone.

Regardless of the circumstances, the taint on Bacon’s character has endured, and it has compromised his literary standing too. “Francis Bacon’s reputation has suffered from the world’s insistence that a moralist should follow his own advice; having recognized vice and folly, he should avoid them,” Haight writes. “But in Bacon knowing and doing were as far apart as they are in others. All his life he wooed the Goddess of Getting-on, only to prove that self-seeking ends in disaster.”

But if Bacon didn’t always practice what his essays preached, he at least had the benefit of working in a genre that tends to forgive inconsistency. We often read essays precisely because of the contradictions they reveal in the writer, perhaps in turn underlining the contradictions we feel in ourselves. There’s more than a bit of this tension in Bacon, who wrote against quick certainty even as he rushed to pat conclusions—or argued against ignorance though he sometimes seemed captive to the insularity of the royal court.

Out of office, Bacon had more time for writing. The tradition of former politicians retiring to their estates to record their reflections is a long one, and it brings the possibility that the public figure will now be at greater ease to reveal his private face. But that kind of relaxed sensibility seemed forever at odds with Bacon’s literary persona. Even in “Of Gardens,” an essay in which he ostensibly muses on the delights of a home landscape, we get very little insight into the particulars of his garden. What unfolds instead is an archly formal treatise on horticultural design, a commentary in which neither the writer nor the reader smells the soil or feels the sun.

There may have been deeper reasons for Bacon’s guardedness about his domestic life. Some biographers have pointed to the possibility that he was gay in a time when homosexuality was considered criminal.

In a letter, Bacon’s mother complained that he was sleeping with one of his male servants. His marriage to Alice Barnham, who came from a politically connected family, seemed loveless. Bacon disinherited her a few months before he died, and she married a household servant ten days after Bacon passed away.

Bacon had a famously dim view of matrimony, at least as it was defined in his day. He made his opinion clear in the opening lines of his essay “Of Marriage and Single Life”: “He that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune; for they are impediments to great enterprises, either of virtue or mischief. Certainly, the best works, and of greatest merit for the public, have proceeded from the unmarried or childless men, which, both in affection and means, have married and endowed the public.”

Anthony Bacon might also have been gay. He was once charged with sodomy in France, but Henri of Navarre intervened to spare him from prosecution.

“Although the question of Bacon’s sexual identity will probably always remain a puzzle, the likelihood that he may have been a homosexual is undeniable,” biographer Perez Zagorin tells readers. “If this was the case, it might throw light on certain elements of his labyrinthine personality that are also reflected in his writings. Homosexuality in England was a statutory crime as well as a social misdemeanor, and Bacon was always a practitioner of the art of self-concealment. One of the maxims he included in a collection of sayings dating from around 1594 was the statement ‘I had rather know than be known.’”

Beneath the shroud surrounding Francis Bacon’s private life, a few eccentrics have suggested an even bigger secret, speculating that he’s the real author of William Shakespeare’s works. That idea, first advanced in the nineteenth century, has been roundly dismissed by serious scholars, and on the face of it, the notion makes no sense. While Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets reveal a writer of dancing ebullience, Bacon strictly avoided flashiness on the page.

“Bacon delighted in presenting practical suggestions for the improvement of virtually all of man’s institutions,” scholar Christopher R. Reaske points out. “His interest in practical solutions is reflected in his simple writing style. His prose was intentionally utilitarian, elevating matter over manner. His purpose, simply stated, was to persuade men that they could do just about everything a little better.”

Bacon’s preoccupation with social improvement led him to science. He didn’t invent the scientific method as we now know it, but his arguments for the importance of reason and objective observation in drawing conclusions helped pave the way for science as a central institution in modern life.

In The New Atlantis, a parable he wrote around 1624, Bacon envisioned a utopian society in which progress was advanced by research and discovery. His ideas helped shape the founding of the Royal Society, a seminal scientific institution, in England in 1660. Bacon also championed science in The Advancement of Learning and other works.

“He aggressively pressed the case for practicing science to improve food production, housing, medicine, and navigation,” Robert P. Crease, a scholar of science, writes of Bacon.

Crease also concedes Bacon’s limitations: “Today’s researchers do not rank Bacon high as a scientist. . . . He was obtuse about the science of his own day, rejecting Copernicus’s idea that the Earth moved about the Sun rather than vice versa.”

Even so, Bacon’s idea of a world in which science informs key policy decisions resonates with special urgency as humanity wrestles with climate change and the continuing implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bacon, a seasoned politician and aspiring scientist, probably wouldn’t be surprised by how knotty the intersection of science and politics has become.

A popular tale about Bacon blames his death on his passion for science. As the story goes, he was riding in his coach when he decided to perform an experiment, purchasing a gutted hen and stuffing it with snow to see how the chill helped preserve it, in the process catching a fatal chill himself.

Gribbin, echoing others who’ve looked into the story, casts doubt on the idea of Bacon spontaneously hopping from a carriage, which “scarcely matches what is known about Bacon’s character.”

Surveying the available evidence, Gribbin concludes that Bacon was probably quite sick already, his decline accelerated by period remedies of saltpeter and opiates.

The image of Bacon felled during an intellectual quest, hunched over an experiment in the snow, is probably a mythical one. But like any myth, it points to some underlying quality that’s meant to be remembered. For Francis Bacon, that hallmark was an inquiring mind. As he breathed his last on Easter Sunday—April 9, 1626—it’s safe to assume that he was asking questions until the end.

That’s the chief thing that still makes him worth reading, whatever the limitations of Bacon’s writing or ideas. He could be smug and self-absorbed, but the ideal of a mind without borders nudged him to think more broadly. “I have taken all knowledge,” he once wrote, “to be my province.”

Nearly four centuries after Francis Bacon’s death, the expanding reaches of that province call us to be as audacious as he was.