Henrietta Mann is a full-blood Cheyenne and a citizen of the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. She is an education leader who has taught at numerous institutions from the University of California, Berkeley, to the University of Montana, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College located on the campus of Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Montana State University. She holds a PhD in American studies from the University of New Mexico and last month was awarded a National Humanities Medal by President Joe Biden.

Mann has been a key figure in the development of Native American studies and the growth of tribal colleges and universities. She testified before Congress and has spoken nationally on higher education for Native Americans. She was the first Indian woman to direct Indian education programs at the Bureau of Indian Affairs and helped design the Native American studies program for the Haskell Indian Nations University. She was the president of Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College and served for many years on the board of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

CHAIR SHELLY LOWE: I’m so delighted that you agreed to be interviewed for our magazine. I want to highlight some of the leaders out there in Native communities. And I want to try to center this conversation on the beauty of Native cultures and Native heritage. I’m hoping you’ll talk about the beauty that you have lived your entire life. The beauty of your culture, your language, your history, and who you are as a Cheyenne woman, and how you grew up in the beauty of your culture.

HENRIETTA MANN: Chronologically, I was born in the year of 1934, which is a significant year for the first nations of this land. The Johnson-O’Malley Act was passed in April and the Indian Reorganization Act was passed in June. Ironically, I was born between those two pieces of legislation, in the month of May, 1934.

There were four generations who lived in a three-room home into which I was born. The home was located in western Oklahoma, in the western part of our territory, which was once the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation. My great grandmother was alive. Her son, my grandfather, and her grandson, who was my father, also lived there.

My great grandmother often said that her daily prayer was to live long enough to see her grandson’s child, whom she had reared from infancy, from either seven or nine months of age, when his mother walked to that next camp.

I was born in an Indian hospital that had just been built. I asked my father once, If your grandmother was a midwife—her name is Voestaa’e, which means White Buffalo Woman—why didn’t she deliver me?

He said, Let me think about that. And the next morning he said, Well, my grandmother was old and your mother was young. And there was this new hospital, and we wanted to make sure that you came to live in a beautiful world. So your mother went to the hospital, he said, but we waited at home for you and were so eager to have you.

The day that you were to come home, we waited for you from sunrise until you arrived in a cradleboard. And, he said, I might mention you had five beaded cradleboards made by different members of our family. I have seen photographs of those five intricately beaded cradleboards leaning, side by side, against the running board of a very early Ford. He said, Everyone was so happy to see you.

The next morning, he said, my grandmother did something culturally important for me. She was also a doctor of horses. One has to understand that we come out of a horse and buffalo culture as Southern Plains Indians, originally from the north. What she did for me she did for all the children that she helped to bring into this world. She took your small body and, he said, held it in a way that Cheyenne men hold their pipes. Then she pointed your head to the southeast direction of the universe, which is the home of one of our foremost powerful spirit beings, the Spirit of Spring.

She introduced you to that sacred, powerful being. Then she pointed your head to the southwest where the second one lives. She went on around the circle, pointing your head to the northwest and, finally, to the northeast. The color symbolism associated with each direction represents the four colors of the relations of this world in which we live, the white, the red, the black, and the yellow races of Earth.

Then she pointed your head upwards to the Great One, Maheo. And then she cushioned you with her hands on the Earth. That was the way of introducing you to the spirit powers of the world as one of the Cheyenne people, the Tsetsehesestaestse, “the people who are alike,” who speak the same language, who share the same culture, and who have walked throughout time with each other.

After she did that, she said a long prayer for you that you live a long life, a very useful life in service to the people, that you never forget your identity as a Cheyenne person, and that you work to make their lives good and happy, especially in this new time that we had walked into with the creation of reservations, boarding schools, and churches. A different time.

My great grandmother’s generation broke that connection, not just with the horse, but with the buffalo, as they reluctantly walked into their reservation headquarters. That was the world into which I came, in which I was introduced to the great spirit powers of the world as one of the Cheyenne people. I lived in this very loving home with a great grandmother, who had seen much brutality and tragedy at the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, which she survived. It was followed four years later by another massacre along the Washita River, in Indian territory, which she also survived.

I often wonder what my life would have been like if she had not survived. Would I even be here? Would I know that, despite tragedy, the people to whom I belong are always hopeful, and that they are a peace-loving people? This is demonstrated by the council of 44 peace chiefs, our traditional form of government.

Our ways came to us out of our sacred mountain far to the north, which sits in the periphery of the Black Hills. That sacred mountain, our teaching mountain, the spiritual center of the Cheyenne universe is called Noaha-vose, which is “the giving hill” or “the hill that teaches.”

From a distance the mountain looks like a reclining bear. As I was told by one of my sun dance instructors, one will find yellow paint—all shades of yellow—in a cavern where the mouth of the bear is.

I went on a journey to that sacred place, and I was just absolutely enthralled with the numerous different shades of yellow, from very pale to gold. Yes, every color of that sacred paint of ours. We cherish the color yellow. It is indicative of the fall time of a person’s life. We also use red and blue, but we cherish the color yellow because it is indicative of maturity and living a life of service, maintaining the culture, making sure that our language continues to live.

And so that place far to the north from Oklahoma is “the giving hill,” the hill that teaches us, and where today many of our Cheyennes go to fast and to pray, to seek direction for life, to renew their identities and walk on sacred ground.

I have visited that place numerous times. We love that place. Tragically and unfortunately, it is a South Dakota state park. We continue this battle to maintain the sanctity of our Indian sacred sites.

And so my great grandmother made that break with the past, and I came in at a different time. I was cherished beyond cherished, and I’m sure taught as few other children of that time were, to speak our language, to learn our life ways, to learn our value systems. And not just learn about them, but to implement them into the way one lives, whether it is to be loving, to be kind, to be respectful, to be understanding, to be at peace in one’s heart. Furthermore, we were expected to always cooperate with other people. Values that we, today, if we would but embrace them would make this world the beautiful place it was when we were planted here.

We look at our place in this world as a place where Maheo the Great One literally planted us in this Earth. So we have spiritual roots that go deeply into the sacred body of our grandmother, the Earth. We work to maintain strong spiritual roots, and we want our children and our grandchildren also to have strong spiritual rootedness in this world. We also want the other colors of our relatives who have come to share this beautiful Earth with us to also have strong roots. Those were things that I learned from the matriarch of the family, who walked to that next camp in 1938, four years after I was born.

My father told me that we were inseparable and said, Though my grandmother was quite old, she would never let your feet touch the ground. She would sit and hold you, and she would carry you. And she sat and talked with you, and what you two talked about must have been good and wonderful. It was her way of teaching me.

I’m sure she must have essentially condensed much of the world into which she was born, which, we believe, was on the plains of the current state of Wyoming in 1853. She saw so much tragedy, but as she sang in her death song, she had also seen beauty. However, she further stated that the thing that is difficult is death, because memories linger. I find it absolutely phenomenal that she, like others of our nation, was attacked along Sand Creek in Colorado Territory, and in Indian Territory, along the Washita River, and yet she said, I have seen good and harsh times, but she was not jaded. She said that was life and that death is difficult when others leave us, completing their journey on Earth to go to that gigantic encampment in the stars, which is a constellation of a circle of stars with nothing in the middle. All our relatives who have ever lived on this Earth live there, except for those that commit suicide. Life to us is a precious onetime gift, and we know that we all go back to live with our relatives in that encampment in the stars, in the star world. But those that commit suicide do not return there.

This tribal teaching illustrates to me the sacredness of life for us, a treasured onetime gift. We walk the Earth but once. And so we are expected to be good-hearted Cheyennes, which is a lifelong quest. I’m still trying to reach that goal.

I learned as a child the ways of the Cheyenne people. I learned the language. And, after I started school, my father’s sister-cousin moved in with us, and would teach me Cheyenne after I got off the school bus, and changed my school dress, of which I didn’t have many, and got into my play clothes. I sat down with her in private until dinner time, as she continued Cheyenne lessons with me.

At dinner, both English and Cheyenne were spoken, because my parents and grandparents realized that I must live in a different world. I wanted to go to school. I wanted to be educated. And down the road from where we lived was an abandoned Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school.

My dad went there and got a chalkboard and got some tiny desks, and converted my mother’s pantry into a little classroom. My older cousins who were in school would come home and teach me. They taught me how to count. They taught me my colors. They taught me the difference between vowels and consonants. I thought that school and education was the most beautiful experience one can have. And it is.

At the age of five, I decided I wanted to go to school, and my parents had to get permission from our Indian agent, who wanted to see me. Now that I look back, I feel like he must have been inspecting me the way my great grandmother inspected horses when she was going to treat them. He walked around me, looked at me, and finally told my mother, Well, she looks like she’ll be able to go to school. He said, Go ahead, enroll her. Then I heard him tell my mother, She’ll probably get tired of it. And when she does, you can take her out of school. You have to be careful what you say around little children because they will listen and repeat it.

When I was in the third or fourth grade, I had my first experience with discrimination. The school nurse, some of the teachers, and some of the parents called the Indian children out into the hallway and searched our heads for lice. I didn’t have any that day, but sometimes I would go and spend the night with some friends. Then my aunt and my mother would always have to check my head.

At the end of the day, I got on the school bus, that big yellow bus that I thought was just the most wonderful of all cars. And I rode for about two miles, maybe three miles, to the taunts of Anglo children saying, “dirty Indian,” “lazy Indian.” Children can be cruel. I just sat and listened, but when I got off the bus and the bus left, I burst out crying.

I saw my grandfather coming down the railroad tracks. We ran to each other. My heart was broken that day. He walked me home and talked to me. And I indicated that I never ever wanted Indian children to be treated the way that I had seen us treated that day. I made a decision that day to become a teacher.

I majored in English. I have two degrees in that discipline and my doctorate required a background in literature. My doctor of philosophy degree is in American studies.

I became a teacher. I taught in junior high and high school. And when Native American studies began proliferating—they were created on the West Coast—I went to teach at the University of California, Berkeley.

Over the 40 years that I taught in higher education at UC Berkeley, at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, and places in between, I had access to younger minds. They deserve to learn about who they are, about our history, our philosophy, our literature, to learn about models of good human beings.

I don’t know that our schools or higher education teach us to be good human beings, but we do learn it in the humanities. We learn about this experience, and this life we share as human beings. That is a phrase that sometimes is applied to us as Indigenous peoples. We know ourselves by our own names, in our own languages. For us, as Cheyennes, we call those who were here first, and who have always been here Xamaavo’estaneo’o, which means Indigenous peoples, but more precisely “the ordinary people of this earth.” We were here first and are taught that we have always been here. We further believe that we are spiritually rooted in the land.

There is much, I believe, we still can share with the world, which right now needs to rebalance itself, to look at the good in all life. And, to me, that’s what the humanities do. I taught Native American literature, which we called “oral and written traditions of the Native American.” Using the terms of the English language, I also taught courses in American Indian religion and philosophy, Cheyenne language and culture, and American Indian history.

What is important are our value systems, and the way we look at the world through our eyes. Those of us who have lived the longest on this Earth were here when the impact of immigration began. Some of our tribal prophecies tell about those that were going to come here. For us Cheyennes, there was a good Cheyenne man, Sweet Medicine, who told us about those strangers who would come from the East. And he said there would be so many that we could not stand before them, and that they would bring different things with them. They would bring something that looked like a long stick, but which spoke with the voice of thunder. And with that stick, they would kill our relatives, the four-leggeds, those that fly, those that live in this earth. And they would use that same instrument to kill us.

Today, as a country and a nation, we are concerned about guns, gun control, and bans on them. We knew that was going to be a problem, even before we ever encountered that first immigrant from Europe, England, all of those places, the Anglo Europeans.

Sweet Medicine also told us that these same people would bring something that looks like sand but tastes very sweet. And he said that those people, those first immigrants would want our land, and they would take it. And we know that that occurred, unfortunately, through the philosophy of Manifest Destiny and cultural imperialism. It’s still out there. It’s still rampant.

And Sweet Medicine said that they would take the land. But he told us, finally, They will ask you for your children and you must say no. Those they take to educate will not know their ways. They will not know anything. He made it an imperative, and now it’s a cultural imperative among some institutions of higher education to teach about the world of Native Americans.

I had thought that we had gone past the days of white supremacy. I hope it doesn’t proliferate. I’m getting close to ninety years of age. I worry about my grandchildren and the world in which they are expected to live. Thank goodness for the continuity of Indian nations and thank goodness that there are such fields of study congruent with our cultures.

Our field of study is the humanities. It includes how we are to be as human beings, but now I hear that some have begun to wonder about the validity of the humanities. Where else are we going to learn to be human? Where else do we get to know what we need to continue to live in a huge community? Where else are we going to learn that we live in one ecosystem, one world that has many, many kinds of people in it.

I am a master language teacher for about a dozen Cheyenne-language apprentices. And I try to teach them words that are contemporary. Last week, I taught them the word for earthquake, (tsehemomo’ohtse-ho’e), meaning the Earth moved, equaling an earthquake. And what happened? The earth moved in Turkey and Syria, and, unfortunately, thousands upon thousands did not survive this earthquake. We have not been responsible in how we have protected or not protected, and cared for, this first mother of ours.

Those are the kinds of teachings that have been passed down to us through the generations, that we learned in our homes. The first universities on this land, in those first school systems that our ancestors created, where we learned what our relationship to those that live in our ecosystem is supposed to be, including the four-legged, those that fly, those that stand rooted in the earth, those that live in the water, the trees. All of life.

Those are the teachings of our grandparents. And those are the kinds of teachings that I certainly tried to include in the four decades or so that I taught Native American studies. I’ve had a wonderful life. I have seen much tragedy. I worry about some of the young, who do not treasure life the way that we were taught to treasure life, because of their inability to live in a world that is so different from that of their grandparents and their great grandparents.

So the humanities have a vital role in teaching us who we are, how we are to relate to each other as two-legged people with five fingers, how we are to respect one another and know that there are different colors for all of our relations. The humanities teach that we live in a very fragile, delicate world, a world dominated by kinship, in which we all live as good relatives, or should. Not just to one another, but to our first mother, our spiritual mother, the Earth. Furthermore, we must all live in good relationship with the air that has become so polluted that it is causing global warming and climate change. Are we preparing our youth to live in that world into which they are walking? It’s certainly what is learned from the humanities, our discipline, that keeps us human.

I grew up in a world that has its own views, but I also went to non-Indian schools. My parents went to boarding schools. And we are hearing so much of the abuse, the physical abuse that generations of our peoples suffered in federal boarding schools both on and off reservations. I would also include spiritual abuse of those who attended those boarding schools.

When I graduated from high school, all of my relatives and friends were going to Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas. I wanted to go. So I sent for applications. I mentioned to my parents that I had. I never did receive any applications. They were, I think, intercepted. My parents said you will not go to a boarding school. They had to work very hard for me to attend college. And I had to work hard, too.

CHAIR LOWE: Now, Henri, you’ve seen major policies enacted in your lifetime. And during the self-determination era, the late sixties, we saw tribal colleges being birthed. What was it like to be part of that movement, that growth, and how can we make sure that we strengthen those Native studies programs and those tribal colleges?

MANN: I have always referred to tribal colleges and universities as institutions that are the dreams of our ancestors, that they have a vital role to play in self-determination.

In 1966, I served on our tribe’s business committee or tribal government. We are two allied tribes as a government, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. Our kinsmen in the north are the Northern Cheyennes, and the kinsmen of the Arapahos in the north are the Northern Arapahos, who share the reservation with the Shoshone in Wyoming.

While I was working on my master’s degree, I wanted to write about Indians. I was working toward my second degree in English. And so I proposed this to my adviser, and was told, no, you can’t. You can’t study about your oral traditions. I asked why not. And it boiled down to, well, there’s no one here to evaluate what you would write about, so you can’t do that.

What does a person do? Sometimes we have to make so many detours in a life of service. I ended up doing my master’s thesis on, of all things, the bird imagery in Jane Eyre as a symbol of love and hope. Those two traits, those values, are very important to us as the people of this land.

So I served on our business committee. And we instituted a scholarship program. We didn’t have much money, but we realized we had to provide some kind of financial assistance to our younger generation whom we wanted to attend colleges and universities.

I was made the chairperson of our education scholarship committee and later went to testify before the House of Representatives on our judgment fund award. We set aside $500,000 to award in grants to those who wanted to pursue higher education. There was nothing called Indian studies. And those boarding schools were being phased out, especially the off-reservation boarding schools, in the sixties.

Finally, we could formulate our own hopes for the future, our programs, our educational programs. We had that educational scholarship fund. Lyndon B. Johnson made his speech to the Congress entitled “The Forgotten American,” which really ushered in self-determination. Finally, we could, once again, really be involved in the education of our children, grandchildren, and others of our community.

At that time, living here in Oklahoma, we no longer had any reservations. We had a territory, which covered essentially nine counties in western Oklahoma. But we thought, okay, we have to support our young people, so they can get a higher education. The tribes assumed the financial responsibility.

It was also around this time that the Kennedy Report was released by the Subcommittee on Indian Education. It called Indian education a “national tragedy” and a “national challenge.” Eventually, Native American studies programs came into existence. Some of them now are departments in higher education. In 1968, the first of tribal colleges and universities, Navajo Community College, now called Diné College, was founded. It was the impetus for the movement that led to about 40 tribal colleges, most of them situated along the Northern Plains. But for once we could say, this is what we want our younger people to learn in higher education, things that are consistent with our unique cultures, as peoples.

I still think tribal colleges have a vital role to play, as do those colleges and universities that have very strong academic units called Native American studies, whether they’re departments, programs, or centers. We have to provide an environment for our young people that is consistent with who they are, so that they can take courses in American Indian history, culture, language, philosophy, spirituality, literature, our oral traditions, our stories, which hold so much of our history and culture within them. Our stories of our beginnings as peoples are different than we find in the Bible in the Book of Genesis.

We have our own stories. That was something that I felt was essential in academic institutions, where I was employed. And self-determination was necessary, still is necessary, will always be necessary, for us who lived on this land first, who have so much that we can teach others about living in harmony and balance with all life.

We have the first educators of America, the first philosophers, the first scientists, the first of everything. And those schools were in the homes of our mothers. Our mothers are the first teachers of our children. And so it is critical that we maintain that kind of learning environment in our homes. I realize that many mothers work outside of the home today, but there is still that vital role. Grandparents, maybe, aunts, and uncles assist in teaching responsibilities. We still carry that responsibility for transmitting knowledge from one generation to another in whatever ways we can. And so tribal colleges and universities certainly have come in to fill that void. Native American studies programs, departments, and courses in other academic disciplines also fill that role.

I want the world for Indian students. I want the world for all the students that I have taught, so that they can really know what peace there is when you live and recognize your place, a very small place in this gigantic world of relationships. And as one of the oldest of elders in the nation to which I belong, the Cheyenne, I include the values that have helped us maintain our cultures: to live in community, to respect all life, to love one another, to cooperate with each other, to be patient, to be kind.

When I started going through the sun dance ceremony, my teachers would always tell me, slow down, walk slowly, take your time. I had to learn to do things in a very slow but deliberate way. I had to learn to walk with balance and harmony, to walk gently on this Earth, to live gently on this Earth, to be respectful of this Earth, to love this Earth.

And if all of us had done that, we would not be facing the kind of crises we are facing today in terms of climate change and global warming. This critical climate crisis is the result of the continuing exploitation of our grandmother, our mother, by those in search of the Earth’s resources that live within her, that constitute her body as our spiritual mother.

Sweet Medicine told us that those people that come from the East that you will meet in the direction from which the sun rises are going to be looking for a certain stone that the Creator put on the Earth in many places. He said it’s the yellow metal that makes them crazy. We’re talking about gold.

It was the discovery of gold in the Pike’s Peak area of Colorado Territory that led to the tragic 1864 Sand Creek Massacre. “Pike’s Peak or Bust” was the slogan as immigrant wagon trains streamed across our hunting lands, carrying unfortunate diseases with them.

I am told about one-half of the Cheyenne Nation had previously perished as a result of the cholera epidemic of 1849. Not to say anything of those other diseases that came to this land. If one wanted to, I think we could safely say that we experienced something like biological germ warfare. There were seven epidemics of smallpox that Russell Thornton in his book American Indian Holocaust and Survival said took our population from over five million people in the contiguous United States down to 250,000.

When we, as this land’s first peoples, were first included in the United States census in 1890, our population had dwindled to 250,000 from millions. Some of it was the result of those seven epidemics of smallpox. Childhood diseases for which our ancestors had no immunity were also carried here.

We know what biological germ warfare is. We know the kinds of change in lifestyles and culture that immigration can bring about. We know what it is to have experienced the unfortunate genocide that our grandparents experienced. I believe that everyone that goes to college should learn that. They also should learn our phenomenal contributions to America. Whether it’s in a very healthy food supply, whether it is in the model for the United States Constitution that Benjamin Franklin brought to their meetings, because he admired the way that the Haudenosaunee governed themselves, the model that Six Nations of this land gave to this country. Medical knowledge. We have contributed much to what we would call the American way of life, but there is little or no general knowledge about the contributions that the first peoples of this land gave to the world.

Willow bark, for example, has medicinal properties and was used to treat headaches and body aches—then it was patented as Bayer Aspirin. We gave that to the world. Our ancestors and the first peoples of this land know what it is to live in community, to share knowledge, to share wisdom, to share values, to be human.

That is what Native American studies continues to do at the universities and institutions where there are such programs, but especially in those tribal colleges and universities that teach for life.

LOWE: If you were going to give advice to people doing work in the humanities, what kind of advice would you give?

MANN: I would say that we all would have to expand our knowledge in the way that individuals like you and I have had to expand our knowledge to live in mainstream America. I write better than I speak, but that comes from learning a foreign language. For me, English was a foreign language.

But I would say that the humanities are vital. They are critical to maintaining that human dimension and that knowledge of who we are as Americans. We need to maintain the continuity of the human essence, the human being, who has the capacity to cry, to learn, to be happy, to be sad. To never negate our responsibility as academicians or teachers to help mold that model American, if there is any model American. To make us aware of the depth and the breadth of what it is to be a human being. Good-hearted ones, loving ones, kind ones. To know that the first peoples of this land moved over, so that others could come to share this place that we all now call home.

Our grandparents were entirely too smart for them to be ignored. They were geniuses. They are still geniuses. And we are told to live in harmony with all of life, to be aware of our responsibility to and for those people that are rooted in the ground, those that fly, those that live in the water, every kind of people that exist in this one environment, in this one world, an ocean of kinship, to know that we are connected one to another. And that vital connection will help to maintain all of humanity as they walk into tomorrow. They have to have the skills and knowledge of what it is to be, in every dimension, a true human being.

LOWE: Is there anything you feel that you have not yet accomplished?

MANN: I wish that I still had all that it takes to go into the classroom and to teach. That’s just me wanting to fulfill the dreams of a little eight-year-old or nine-year-old girl to see that Indian children are treated with love and dignity and respect for what their grandparents have given to the world.

LOWE: I think you’ve said a lot already, but is there anything else you want to say to young Native people?

MANN: I would tell them, Be exceptionally proud of who you are. You come from a long line of philosophers and geniuses. A long line of them. Don’t ever forget them and the gifts that they give to you, in terms of knowledge, of teaching you in their own way what it is to survive, because we have survived until today. And that is what I want for all of them, to survive for all time.

I want them to make sure that their education is balanced. And that it consists not only of mainstream thinking, that it should also be balanced by the knowledge and the traditions of those that have lived on this land the longest. I would like for them to know that they need to always be hopeful, that they have the means to build a better future than the one we live in today. And that we, as the first peoples of this land, continue to throw our wishes and prayers over them as they walk into that unknown tomorrow.

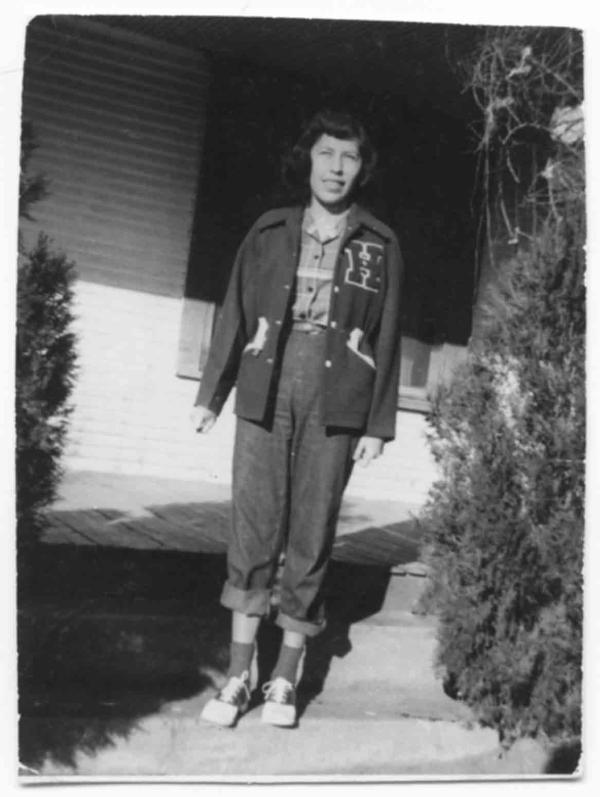

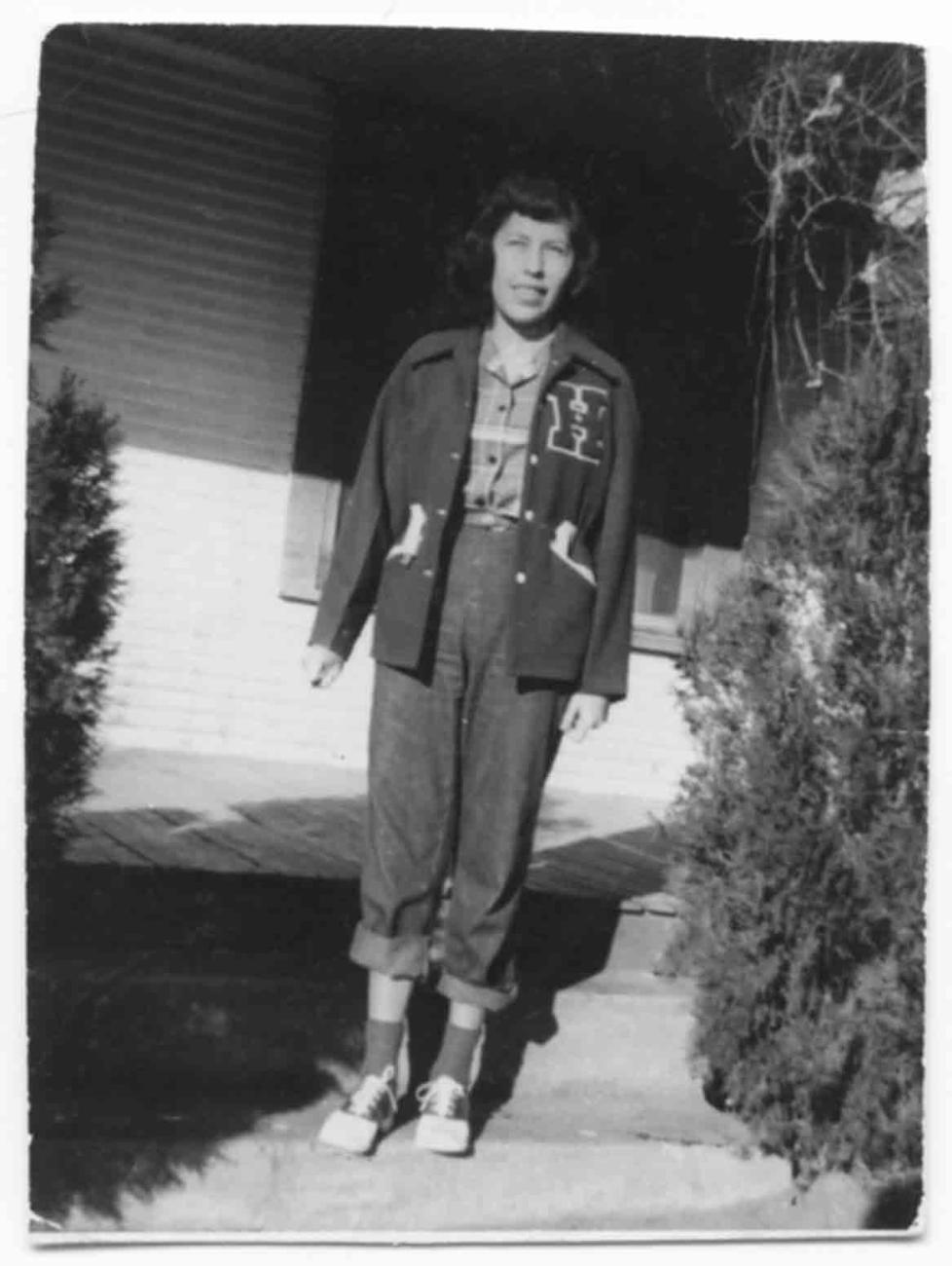

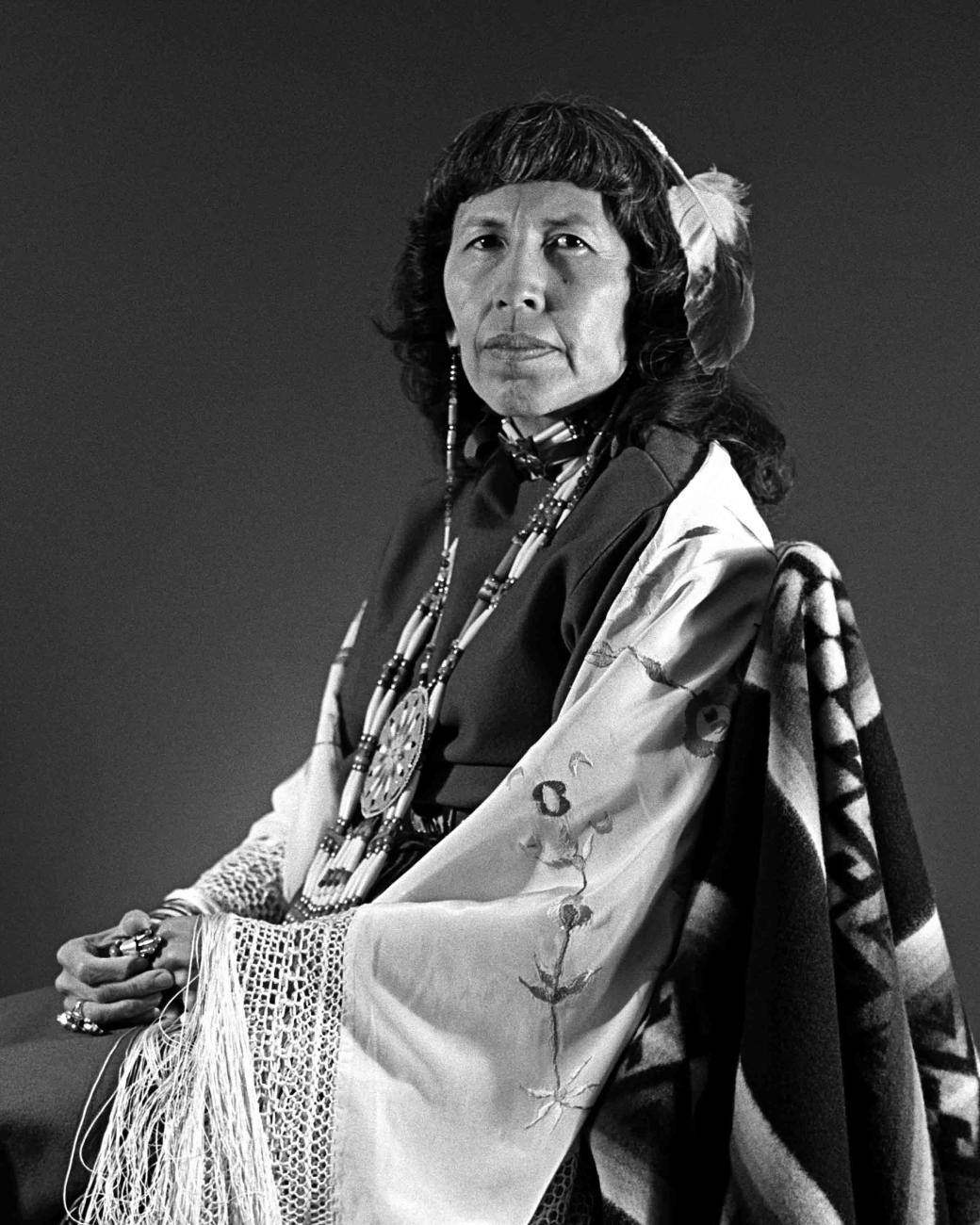

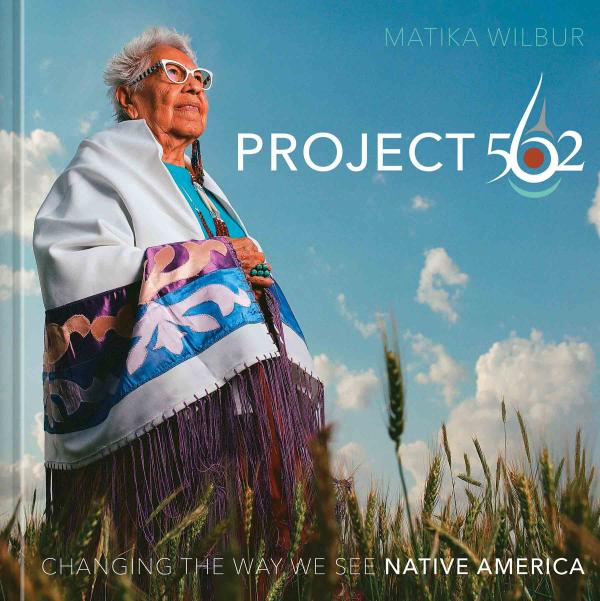

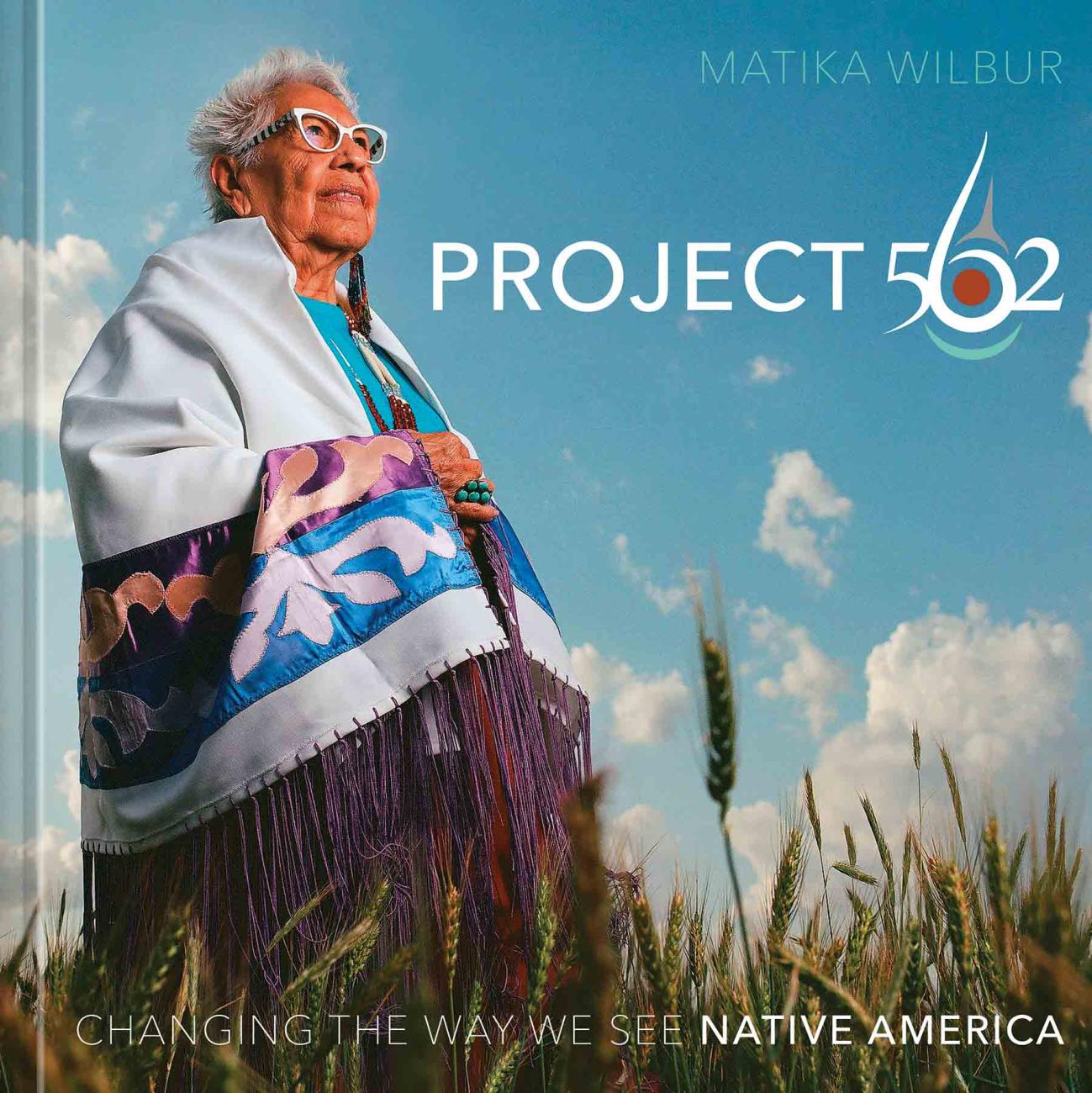

In 2012, Matika Wilbur of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes set out to visit the more than 562 Native American sovereign territories in the United States. Her book, Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America, publication date April 5, 2023 (Ten Speed Press), with Henrietta Mann on the cover, features hundreds of photos and stories, supplying a needed counternarrative to “the one-dimensional and archaic stereotypes of Native people in mainstream media.” A contributor to the New York Times, National Geographic, and many other publications, Wilbur seeks to do justice “to the richness, diversity, and lived experiences of Indian Country.”