Visualizing the "New Urbanism"

The “New Urbanism” is barely thirty years old. But the goals of the upstart planning and design movement are timeless: the creation of towns and cities shaped to fit human needs and sensibilities, in which ample, walkable public spaces foster a sense of community, in which neighborhoods combine homes and businesses for a diverse population, and in which people can coexist comfortably with automobiles.

To be sure, those exemplary conditions exist in many places around the globe. Some were shaped hundreds of years ago. Some were built from scratch as “new towns.” Some are urban areas that have been retrofitted into more humane environs. But in the United States and elsewhere the opposite is more often and more conspicuously the case: moribund city cores surrounded by concentric accretions of suburbs from which it takes ever more time, hydrocarbons and anxiety to get to work.

“The New Urbanism,” says one of its earliest proponents, Washington architect and international designer Dhiru Thadani, is “the antithesis of the suburban sprawl paradigm and fossil-fuel dependency. It is a movement that promotes the return to compact, walkable, well connected, mixed-use and mixed-income neighborhood development” organized on three spatial scales — “region; city, town and neighborhood; and block, street, and building.”

If that outcome is so self-evidently desirable, why aren’t there more such spaces?

One reason, Thadani believes, is that “there is no common language in the professions of architecture and planning as there is in medicine and law. Words used to describe the built environment are constantly misused. Words such as center, park, village, square, avenue, boulevard and space have lost their true meanings. There is a difference between an avenue, a boulevard, a street, a road and a drive — yet planners, traffic engineers and developers constantly misuse these words.”

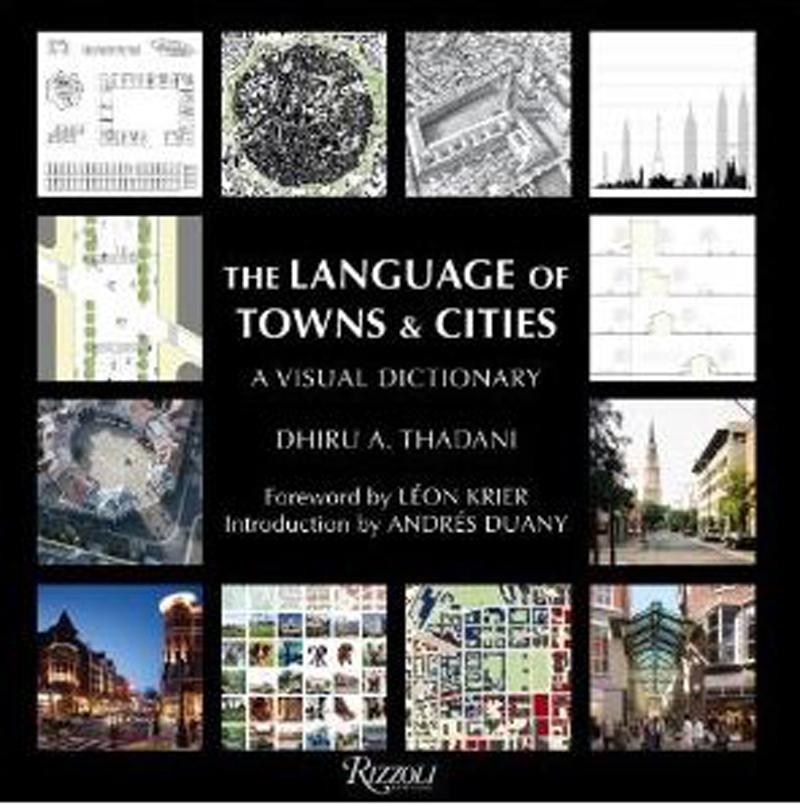

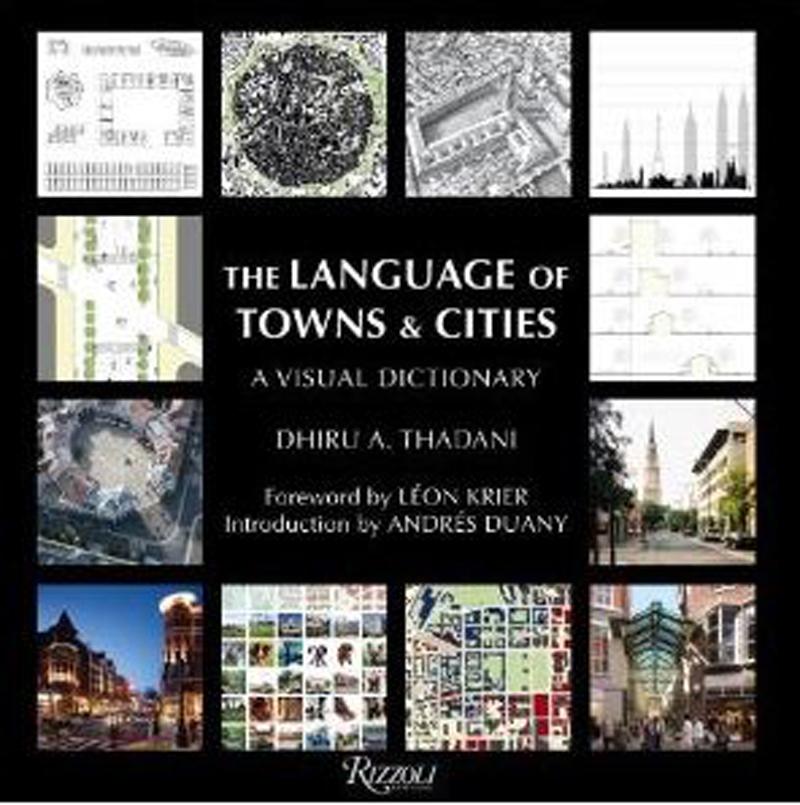

That is why he applied for NEH support to produce The Language of Towns and Cities: A Visual Dictionary, an 800-page “encyclodictionary” of terms and concepts published in December 2010.

“The architecture and planning professions have lost their respect and standing in society,” Thadani says. “This is partially due to the loss of a common language that describes particular conditions in the built environment. Professionals cannot even communicate clearly with each other, and the built environment suffers as seen across the United States and globally. I hope this book helps empower the design profession.”

Thadani’s compendium includes material from 52 contributors worldwide. Arranged alphabetically and copiously illustrated with photos and drawings, the entries deal with broad ideas such as dwelling density, accessibility and zoning, technical issues such as intersection typography, examinations of individual model towns and landmarks, and profiles of noted designers.

“This expansive work will quickly become a standard reference resource for architects, historians, educators, and anyone interested to learn about architecture and urban planning,” says Joshua Sternfeld, Senior Program Officer at NEH’s Division of Preservation and Access. “It covers a range of historical and contemporary topics from early examples in ancient Greece and Rome, to international examples in India, to pioneer urban planners such as Thomas Jefferson and Daniel Burnham.”

The book has garnered favorable notices. One reviewer observed that reading the entries is “like taking a very enjoyable short course in urban design.” Another said it is “not only useful for the planning or architecture professional but also the everyday citizen trying to understand the complexities of the city… .” Prominent European architect and urban planner Rob Krier wrote that “It is more than a handbook. It is a guide.”

NEH seemed a natural place for Thadani to seek support for the project because the New Urbanism is as much about culture and society as it is about architecture and traffic. And its effects are measured in human values, social interactions and collective behavior.

“The primary difference between a city and suburb or rural land,” Thadani says, “is that a true city comprises a civic, public realm and a private realm. The civic realm is defined by civic buildings and civic spaces, which includes streets and squares. The civic realm instills and inspires civic pride and uplifts the human spirit. The civic institutions define a society and its values, and should be celebrated with embellished architecture and prominent locations. The civic realm also suggests a particular behavior and decorum. Humanities encourage self-reflection which develops personal consciousness and an active sense of civic duty, necessary for a city/culture to survive. The private realm, in contrast, should have quieter architecture, and less embellishment.”

Thadani — a charter member of the Congress for the New Urbanism — has been awarded the 2011 Seaside Prize, which is “awarded annually to individuals or organizations that have made significant contributions to the quality and character of our communities” by the Seaside Institute in Florida, which espouses New Urbanism principles.