The War 150 Years Later

As we mark the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, a selection of past, present, and future humanities projects.

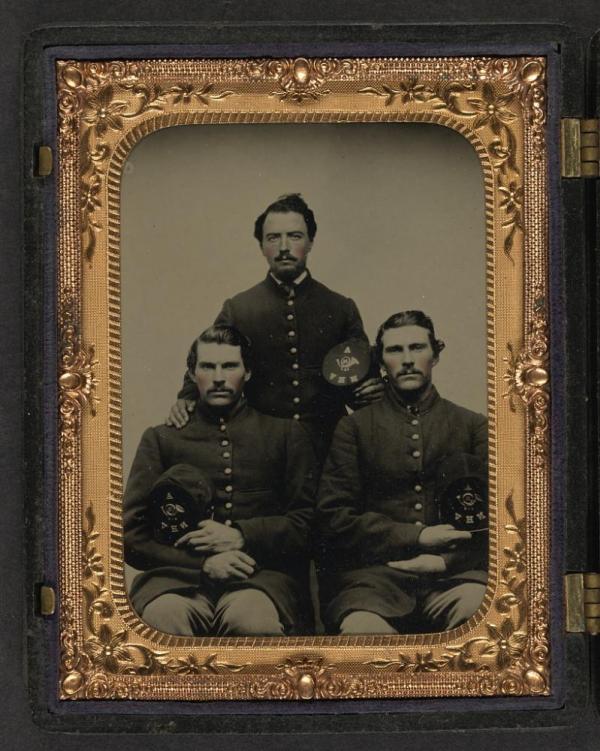

Twins Bartlett and John Ellsworth pictured with their brother Samuel. All three fought with Company A of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry. Three months after enlisting, Bartlett died from disease while serving in Potomac Creek, Virginia.

Credit: Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress

Twins Bartlett and John Ellsworth pictured with their brother Samuel. All three fought with Company A of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry. Three months after enlisting, Bartlett died from disease while serving in Potomac Creek, Virginia.

Credit: Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs, Library of Congress

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the sixteenth president of the United States.

He came by rail from Illinois, speaking to crowds along the route from the back of the train. Welcoming the opportunity to show Americans the face of their new president, he joked that in seeing theirs he was getting the better end of the bargain. Seven states had seceded from the Union, but he called the crisis “artificial,” and dismissed the Confederacy (which days earlier had inaugurated its own president, Jefferson Davis) as something cooked up by scheming politicians.

Lincoln made stops in Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. In Manhattan he attended the opera, but he did not always pass for a gentleman and was the object of some unflattering comments among the city’s elite.

Responding to warnings of an assassination plot, Lincoln changed plans for the last leg of the journey, canceling a visit to the Maryland capital. But crossing into slave territory could not be avoided. Lincoln’s train made a stop in Baltimore and was soon on its way. Later that day, the president-elect arrived in Washington all but unannounced and, as some reports had it, incognito.

Lincoln’s election had split the national vote between North and South. He was the country’s first avowedly antislavery president. Several moments on Inauguration Day betrayed the grim irregularity of this fact and what it foreshadowed for the United States of America.

At the U.S. Capitol, riflemen were posted at the windows and on the roofs of nearby buildings. The oath of office was administered by Chief Justice Roger Taney, author of the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, which helped overturn the Missouri Compromise and extended slavery to Western states. From a platform on the east steps of the dome-less Capitol, a work in progress like the nation it represented, Lincoln spoke to a crowd numbering in the thousands.

The tone of the speech was conciliatory: “There will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.” But Lincoln’s words on the subject of disunion were blunt: “Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy.”

Lincoln closed by calling on “the better angels of our nature.” The call went unanswered. Open conflict began April 12 at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. The new president ordered up additional troops and another four states seceded. So began the Civil War.

2011 marked the war’s 150th anniversary, its sesquicentennial, as already recalled in numerous events, public and private, local and national. NEH has helped fund scores of programs and projects dedicated to improving our understanding of this terrible, great, and liberating event.

Edward Ayers—the historian and educational innovator who brought us the celebrated NEH-supported Valley of the Shadow digital history of the Civil War—has edited a selection of contemporaneous writings and exceptional pieces of history-writing for a Civil War reader issued by NEH in partnership with the American Library Association. America’s War, along with March by Geraldine Brooks and Crossroads of Freedom by James McPherson, is being distributed to 213 libraries nationwide for scholar-led discussion programs.

Robert E. Lee was the subject of an American Experience documentary that aired on PBS in 2011. He is today remembered as a great Confederate warrior, though his fidelity to the South was not taken for granted in 1861. At Blair House, a short walk up the street from the White House, Lincoln offered Lee command of the U.S. Army. Lee’s sense of kinship, however, kept the Virginian from accepting. Resigning his post in the U.S. Army, he would become the Confederate commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Over the years, NEH has supported numerous Civil War-related American Experience documentaries, ranging in subject from the life of Frederick Douglass, the great writer, orator, and abolitionist, to the marriage of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, to Reconstruction, the so-called “second Civil War.” More recently, American Experience has been documenting how American society and culture responded to astonishing loss of life (some 620,000 Americans) incurred during the war. This Republic of Suffering takes its title and intellectual approach from the award-winning Civil-War history written by Drew Gilpin Faust, who happened to be NEH’s 2011 Jefferson Lecturer. The lecture is the highest honor in the humanities bestowed by the U.S. government.

Another new American Experience documentary in the works tells the story of the religiously inspired moral reformers who led the fight for the abolition of slavery, a passionate group whom the politically astute Abraham Lincoln often kept at arm’s length.

Through NEH’s We the People Bookshelf, four thousand copies of The Civil War, the unforgettable, eleven-hour-long, NEH-supported, Emmy Award-winning Ken Burns documentary, were distributed to schools and public libraries, along with seventeen books on the theme of “a more perfect union.” The Civil War has spawned many imitators in recent years but has remained the most successful television documentary of its kind. Among other accomplishments, it reintroduced audiences and history buffs to Shelby Foote and his magisterial three-volume history of the war. The novelist, once bruited as the heir to William Faulkner, though never so celebrated, began complaining about all the attention that came his way after the documentary first aired in 1990.

Four NEH-supported traveling exhibits from the Abraham Lincoln bicentennial in 2009 made the rounds. “Lincoln: The Constitution and the Civil War,” run by the American Library Association, explored slavery, secession, and wartime civil liberties as constitutional crises. The exhibit’s tour has been expanded, and will travel to a total of 50 public, academic, and special libraries through 2015. “Abraham Lincoln: A Man of His Time, A Man for All Times” looked at the rail splitter’s life and legacy.

“Forever Free: Abraham Lincoln’s Journey to Emancipation,” created by the Huntington Library, drew attention to the evolution of Lincoln’s thinking on slavery, about which, after years of reflection, he finally said, “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.”

Log-cabin lore and the “right to rise” are themes of “Abraham Lincoln: Self-Made in America,” which examines the arc of Lincoln’s life from humble birth to high office to his assassination.

Other Civil War-related exhibitions included “Lincoln and New York,” a major exhibit at the New-York Historical Society, which also partnered with the Virginia Historical Society on an exhibition devoted to Generals Grant and Lee, now a traveling exhibition. The Catoctin Center for Regional Studies at Frederick Community College in Maryland has received a grant for “Crossroads of War: The Civil War and the Home Front in the Mid-Atlantic Border Region,” a series of lectures, conferences, and tours devoted to this part of the country during wartime.

Virginia was one of the states to join the Confederacy after the attack on Fort Sumter, whereupon Richmond replaced Montgomery, Alabama, as the rebel capital. And, of course, the state was the stage for several important battles, including Bull Run and Fredericksburg. The museum exhibition “An American Turning Point: The Civil War in Virginia” is supported by a $1 million NEH grant to the Virginia Sesquicentennial of the American Civil War Commission. The exhibition opened in Richmond in 2011, and travels to six other cities in the state, after which a smaller version circulates to other venues.

Many Americans will decide to revisit the Civil War through the printed word. NEH has supported quite a shelf of Civil War histories over the years, starting with Road to Disunion, William Freehling’s superb two-volume study of the antebellum South. Another important study looking at prewar America, also completed with NEH assistance, was the 2004 Pulitzer Prize-winning A Nation under Our Feet by Steven Hahn, which examined the political lives of black Americans from slavery in the rural South to the Great Migration.

Don Fehrenbacher’s 1978 book The Dred Scott Case, written with NEH support, won the Pulitzer as well. Fehrenbacher, one of the great lights of Lincoln scholarship, examined the Supreme Court decision that Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan (ranked by modern historians as one of the worst chief executives ever), had hoped would settle the legal and political issue of slavery once and for all.

In 1989, a Pulitzer Prize went to James McPherson’s much-loved, one-volume history of the war, Battle Cry of Freedom, which was supported with an NEH research fellowship. Celebrated for his careful blend of fine scholarship and powerful storytelling, McPherson marches the reader at a stately pace through social, political, and military history from the halls of Montezuma to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment and Lincoln’s assassination.

For an earthier take on the Civil War, one can put on a pair of hiking boots and head off into the parklands with a copy of the Civil War Battlefield Guide, published with NEH support in 1990, and revised in 1998, by the Conservation Fund.

A book about Lincoln himself, from his own point of view, was the goal of David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln Prize-winning 1995 biography. If the future president seemed less than formidable as he arrived in Washington in 1861, so did he seem many years later to Donald, who called him “one of the least experienced and poorly prepared men ever elected to high office.” In that same sentence, Donald also called him “the greatest American president.”

The aftermath of the Civil War was the subject of Eric Foner’s classic Bancroft Prize-winning Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863–1877. Called by Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris a work of “stylistic genius,” Foner’s account sought to move beyond the revisionism that had begun with W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction in America and provide a newly coherent history that returned the freedman to the center of this important national drama.

New NEH-supported books limning the issues of race, slavery, and the Civil War include Daniel Sharfstein’s The Invisible Line, a chronicle of three families who, in the course of generations, crossed American color lines, and An Example for All the Land, Kate Masur’s study of emancipation in Washington, D.C. Ongoing research projects include a study of suicide and other psychological maladies related to the war in the South and an examination of literacy among ex-slaves who, like Frederick Douglass before them, increasingly exercised their newfound freedom through the act of reading. Meanwhile, an interdisciplinary team of scholars at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, is collecting data for a digital resource called Civil War Washington, highlighting the role of the nation’s capital as a hub of political and social change brought on by the war.

Underlying so many works of history is the careful, decades-long work of collecting and editing historical papers, the indispensable primary documents of our national memory. NEH has supported many such projects: the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, the Papers of Jefferson Davis, the Freedmen and Southern Society Project, the Papers of Andrew Johnson, Race, Slavery and Free Blacks: Petitions to Southern Legislatures and County Courts, 1776–1867, the Frederick Douglass Papers, Walt Whitman’s Civil War writings, the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, the Thaddeus Stevens Papers, and the Papers of John C. Calhoun. An all-digital archive, the Papers of the Kentucky Civil War Governors, has just gotten started. It promises to bring together documents from three Union governors and two Confederate governors who led the contested border state from 1861 to 1865.

Indeed, papers do not always refer to paper anymore. Great scholarly and public collections are increasingly accessible online. The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database has brought together collections previously scattered in archives around the world and is slowly transforming our understanding of how the abduction, shipment, and sale of Africans shaped several North and South American countries. Among its many fascinating lessons is the sheer number of slaves that were transported: Prior to the 1820s, four times as many African slaves crossed the Atlantic as Europeans.

There are many other lessons, as well as interactive maps and timelines, to be found for classroom use on EDSITEment, NEH’s educational web portal. The Civil War-related curricula include, for grades 9–12, A House Dividing: The Growing Crisis of Sectionalism in Antebellum America, Abraham Lincoln on the American Union: “A Word Fitly Spoken,” and The American Civil War: “A Terrible Swift Sword.” For grades 6–8, among much other material, is Life in the North and South 1847–1861.

Over the years NEH has supported numerous digital media projects that have shed light on the great issues and events of history. Through the National Digital Newspaper Program, the Library of Congress posts on the site “Chronicling America” contents from a huge collection of historic newspapers from 1836 to 1922. It began posting Civil War-era newspapers in 2010. The previously mentioned Ed Ayers and the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond have undertaken a digital mapping project to visualize the social geography of emancipation.

NEH also supports institutions dedicated to illuminating the Civil War through the humanities. The Richards Civil War Era Center at Pennsylvania State University received a $1 million challenge grant to support its programming on the history of American freedom from the Founding to the Civil Rights era. The Lincoln Studies Center at Knox College received an $850,000 challenge grant to support its staff, online Lincoln resources, and educational programs. The Historic Preservation Trust of Lancaster County got a $375,000 challenge grant to help restore six historic properties and a recently discovered Underground Railroad cistern. The Lancaster Trust plans to use the buildings and cistern for interpretive programming devoted to the abolitionist legacies of Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith.

The Civil War tourist (you know, tourist in a good way) may also consider such NEH-supported sites as President Lincoln’s Cottage, which received $260,000 to support interpretation for exhibitions and tours. The Conner Prairie Museum has received $300,000 to support a participatory multimedia experience for visitors to relive (safely) the Confederate raid on Indiana that occurred in July 1863. In case anyone is injured (highly unlikely, of course), they could head to the Mutter Museum of Philadelphia for an NEH-supported exhibition on Civil War medicine as practiced at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (though perhaps the local hospital is, all in all, a better choice).

Hundreds of middle schoolers have been visiting historic battlefields, from Manassas to Gettysburg, through The Journey Through Hallowed Ground. With a $165,000 grant, this program guides students as they research local Civil War history and make short films based on the stories they collect.

Various materials relating to the Civil War have been supported by NEH Preservation and Access grants at large and small institutions alike. With NEH assistance, the Pennsylvania Heritage Society is conserving and archiving 2,568 muster rolls representing every Pennsylvania soldier who served. The Grand Army of the Republic Civil War Museum and Library and the Fifth Maine Regiment Museum have both received modest grants to help preserve and store their history collections.

Schoolteachers and college faculty are the intended audience of NEH Summer Seminars, Institutes, and Landmark Workshops, many of which take up the Civil War as their subject. In 2010 and 2011, two hundred and forty K–12 teachers visited battlefields along the Missouri-Kansas border to study the clashing cultures and political beliefs involved in the guerilla violence along state lines. Middle Tennessee State University organized workshops in and around Nashville to examine the local history of occupation and emancipation. Wilson’s Creek, the war’s first major battle west of the Mississippi, is the subject of a Landmark Workshop in Missouri and run out of Drury University.

Abolitionism and the Underground Railroad were studied by groups of schoolteachers at Colgate University in 2010 and 2011. Rochester, New York, was rife with the nineteenth-century reformist spirit, and several key abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, hung their hats there, as did, in 2011, a group of educators and public historians studying abolitionism, women’s rights, and religious revivalism. For four years in a row, groups of schoolteachers have attended weeklong workshops at Southern Illinois University–Edwardsville to examine “Abraham Lincoln and the Forging of Modern America.” African-American history in the Low Country is Topic A at a Civil War-related workshop for teachers run by the Georgia Historical Society. African-American history was the subject of another Landmarks Workshop, which took place in the nation’s capital in both 2007 and 2008.

In 2009 and 2011, Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, hosted a five-week institute for high school teachers on “Cotton Culture in the South from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement.” Slavery in New England was the lesson for thirty schoolteachers at the Rhode Island Historical Society. Five times in recent years, the Apprend Foundation has hosted teachers in the North Carolina Piedmont for workshops relating to the lives and businesses of Thomas Day, a free black man and celebrated cabinetmaker, and Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave who made a living as a dressmaker in the Lincoln White House.

In 2011, the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, hosted two groups of schoolteachers to learn about the role of New Bedford in the Underground Railroad. In 2012, college faculty and university teachers attend a two-week institute studying the visual culture of the Civil War at the City University of New York Graduate Center. And twice in recent years, the Library Company of Philadelphia has run four-week summer seminars on the abolitionist movement.

A group of community college faculty study war, death, and remembrance at the University of Mississippi, while college and university teachers examine new approaches to Civil War scholarship in a summer institute offered by the Georgia Historical Society. Students also benefit from a chairman’s grant to develop a National History Day Civil War teacher’s guide.

On July 4, 1861, as James McPherson relates in Battle Cry of Freedom, President Lincoln struck a different tone from what he’d chosen for the inaugural. “Our popular government has often been called an experiment,” he said. “Two points in it, our people have already settled—the successful establishing, and the successful administering of it. One still remains—its successful maintenance against a formidable internal attempt to overthrow it.”