Post-War Progress: Civil Rights and the End of Segregation

Creative Commons

Creative Commons

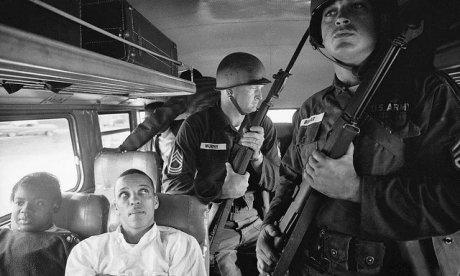

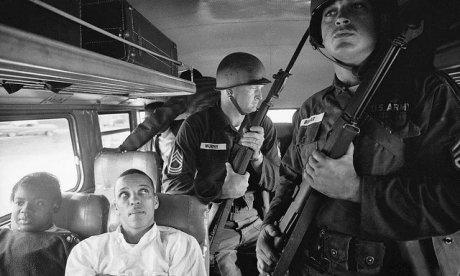

After WWII cemented the status of the United States as a global superpower, the nation underwent tremendous changes in economic growth, social development, urbanization and politics. One fundamental change that occurred was the transformation of millions of everyday black Americans into activists and participants in what became known as the Civil Rights Movement. Frustrated with the slow pace of progress since the Civil War, and wishing to fully participate in the prosperity of postwar America, leaders and organizations arose to once and for all bring about racial equality and progress on both national and local scales. Average but brave black American citizens in Kansas, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Tennessee staged sit-ins at lunch counters that refused them equal service with whites. Black and white idealist students challenged segregation by riding together on interstate buses from Washington, DC to New Orleans, facing violent assault and mass arrests along the way but also drawing the attention of reporters and President Kennedy. Martin Luther King, Jr. stepped forth as a leading national figure who advocated nonviolent protest, marches and moral persuasion in response to threats and as a general strategy, but he competed with other voices, such as Malcolm X, who initially called for cultural black nationalism and a separate black nation as the only way to secure African-Americans’ rights and liberty. Artists, musicians and poets crafted their own individual responses to the movement and the restlessness of the era -- Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun and Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” being examples spanning the range of emotional experiences of the period. Legally, suits were successfully filed to desegregate public schools (Brown v. Board of Education) and legalize interracial marriage (Loving v. Virginia), the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Acts of 1965 were pushed through Congress by President Johnson, and in 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the nation’s first black Supreme Court Justice. Sports became desegregated after the integration of baseball by Jackie Robinson, and major Hollywood films, such as To Kill a Mockingbird and In the Heat of the Night, began openly tackling issues of race and broadening awareness of social disparities to national audiences.

The era, however, was not without its setbacks – both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated before the end of the 1960s; activists in Mississippi including Medgar Evers and three interracial voting rights activists, were brutally murdered in 1964; and frustrations with police brutality and the economic decline of inner cities exploded into fiery riots, laying waste to large sections of Newark, NJ, New York City, Los Angeles, Oakland and Detroit toward the end of that decade. Despite moments of sorrow, though, the movement continued forward, and black Americans by the end of the 20th century had made gains in rights and equality never before achieved nationwide. Delve into the movement and witness great moments of change and perseverance at EDSITEment, NEH’s educational website.