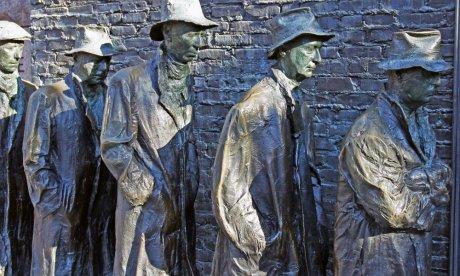

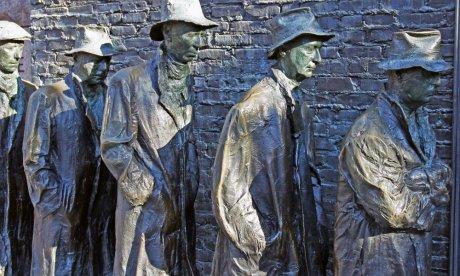

A Great Depression and a New Deal

Chris Flynn/ NEH

Chris Flynn/ NEH

After the Stock Market Crash of October 1929 and the worldwide collapse of economic prosperity, Americans were eager for solutions and political change. African-Americans in the North found themselves allying with other reformist groups and ethnic voting blocs in supporting the Democratic Party and its presidential candidate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in the election of 1932. Roosevelt won with the electoral power of this “New Deal Coalition,” and once in office began organizing a rapid and fundamental series of changes to the Federal government and its role in economic and social affairs.

One such reform was the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which constituted a method for the government to hire young workers left jobless by persistent high unemployment. Over three million men were hired by the CCC between 1933 and 1942, a quarter-million of who were black. However, while blacks were afforded a share of economic stability because of CCC participation, their treatment as equals was prevented by enforced segregation of work teams in the South and discrimination from CCC leadership. The discrimination faced by blacks participating in New Deal programs did not go unnoticed, nonetheless, in the White House, and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt emerged as a voice calling for equal treatment and desegregation inside the halls of power and in public. When the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to host black contralto Marian Anderson at Constitution Hall in 1939, Eleanor stepped forth to invite the singer to perform at the Lincoln Memorial, attracting media notice and a far larger crowd that the segregated hall could have ever hosted for the performance. Simultaneously, Roosevelt worked behind the scenes to support the NAACP in bringing forth legislation to make lynching a Federal crime; yet, despite heavy public debate and private presidential sympathy, the bill failed in the Senate. Progress for racial justice during this period often came in the form of two steps forward and one step back, but the sense that better times were just around the corner would not recede. Learn more about the New Deal’s successes in expanding equality and failed chances at EDSITEment, the National Endowment for the Humanities' educational website.