Dr. Livingstone, Illuminated

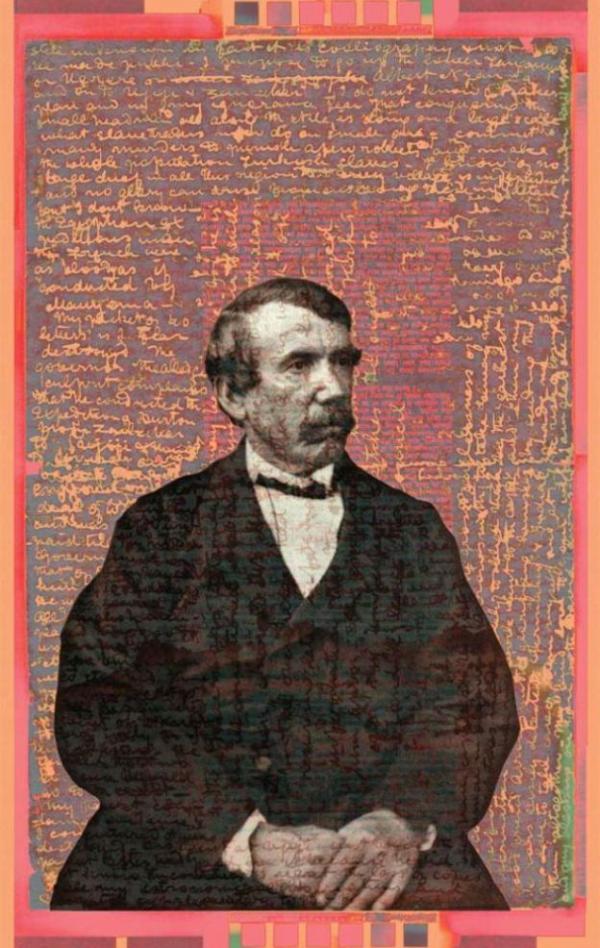

David Livingstone, circa 1865. A U.S.-British team has used high-tech imaging techniques to reveal what had been a faded, indecipherable field diary.

Credit: Adoc-photos/ Art Resource, NY; (letter) Peter and Njema Beard

David Livingstone, circa 1865. A U.S.-British team has used high-tech imaging techniques to reveal what had been a faded, indecipherable field diary.

Credit: Adoc-photos/ Art Resource, NY; (letter) Peter and Njema Beard

For over a century, the stories traditionally told of the explorer David Livingstone’s last journey to Africa relied heavily on the eulogistic portrayal of the man published by his friend Horace Waller in 1874, a year after Livingstone’s death. Waller based his account on Livingstone’s personally edited and redacted journals, which reported events Livingstone witnessed during his last expedition, including the horrific massacre in 1871 of 400 innocent people at the hands of slave traders in the town of Nyangwe (in modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo).

Now, using cutting-edge digital imaging technology, a team of scholars funded by an NEH grant has restored Livingstone’s original, unedited field diary from 1871 – until now faded and damaged to the point of illegibility – to reveal a markedly different image of the near saintly Livingstone readers encountered in the past. Livingstone’s 1871 Field Diary: A Multispectral Critical Edition, which is hosted online at UCLA’s library website, gives visitors a chance to consider the all-too-human image of Livingstone emerging from the text, and a backstage view of the high-tech techniques used to salvage Livingstone’s original account.

The online version also allows readers to compare all three versions of Livingstone’s 1871 diary - the original, the edited, and the posthumously published accounts - side by side, which can yield fascinating variances in Livingstone’s narrative. Dr. Adrian Wisnicki, a scholar from the Indiana University of Pennsylvania who led the team that deciphered the diary, notes that Livingstone’s original account is especially remarkable for the explorer's raw, passionate (and in the case of the massacre, furious) reactions to incidents that merited a more muted response in later versions. For example, whereas in his later account of the massacre Livingstone seeks to find those responsible for the atrocity and see that they are held responsible, in the unedited 1871 diary his demands are more specific: The attackers should be found, he urges, and their heads displayed on pikes.

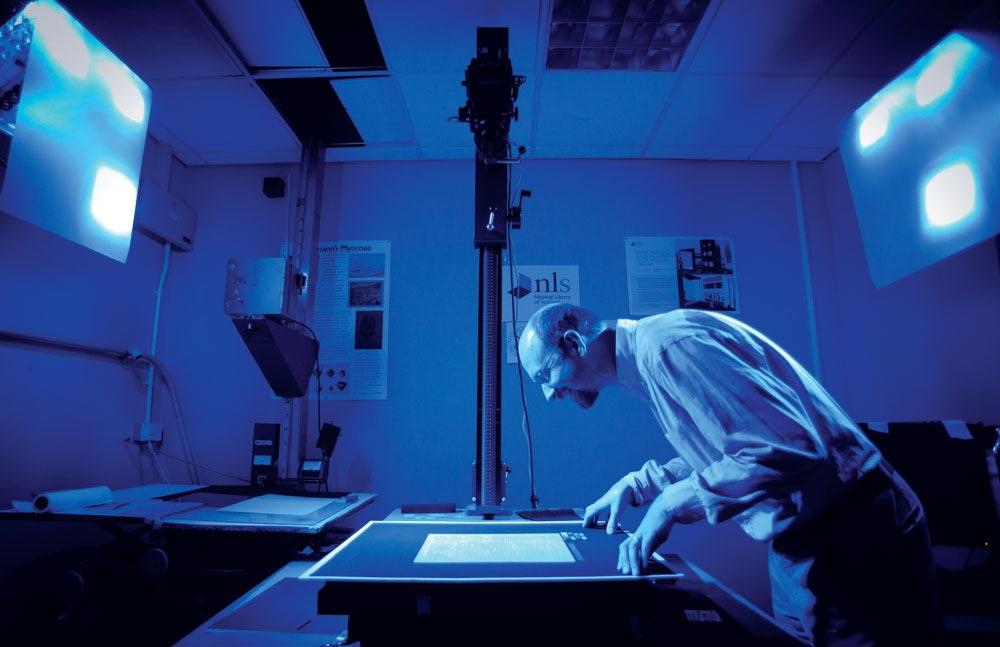

Even before the massacre, the year 1871 found Livingstone struggling with extreme circumstances, which account for why the original diary was inaccessible until now. Stranded in Central Africa, already a year into an itinerary he had intended to last no more than six months, desperately bargaining with locals for a canoe so that he could traverse the Lualaba river, Livingstone had all but run out of writing paper and had depleted his store of ink. In order to maintain records of his exploration, he fashioned a field diary out of a copy of The London Standard newspaper, and resorted to writing over the newspaper print with a locally sourced reddish clothing dye.

This makeshift writing apparatus produced a diary that would not age well, and left Wisnicki's team facing two major obstacles: the improvised ink used by Livingstone had faded almost completely away over time; and the newspaper print, across which Livingstone had written at a 90 degree angle, competed with explorer’s own script.

Advanced spectral imaging technology allowed the team to illuminate Livingstone’s faded script while subtracting out the newspaper type. (For a fuller account of the use of spectral imaging with historical documents, see Anna Gillis’s article on the Livingstone diary project in HUMANITIES magazine.) After this process was complete, transcribing Livingstone’s script was relatively straightforward. “One good thing about Livingstone is that compared to other 19th-century explorers, he had very good handwriting,” Wisnicki joked.

Besides the revelations about the life and times of the famous explorer that are emerging from the multispectral edition of the Livingstone 1871 diary, the project team has also documented its process and techniques as a model for future scholars working to recover faded, erased, or otherwise illegible texts. Mike Toth, leader of the scientific team performing and recording the spectral imaging scans, argues that this pilot project has broken new ground in the application of advanced digital imaging and data management in the humanities.

As scholars like the Livingstone 1871 team devise optimal imaging methods for the texts and media of more and more eras, Toth said, researchers are opening up "new frontiers for cross-disciplinary collaboration in the technical processing and scholarly study of digitized cultural objects.”

“We all feel that it has been a privilege to collaborate on this project that the NEH enabled and for me personally it has been one of the highlights of my professional career,” Wisnicki said. “We have not only achieved the majority of our objectives, but have laid the groundwork for future collaborations with project partners such as the David Livingstone Centre near Glasgow, the National Library of Scotland, and the UCLA Digital Library Program.”

Livingstone 1871 Diary Online: http://livingstone.library.ucla.edu/1871diary/index.htm