Autobiography of Mark Twain

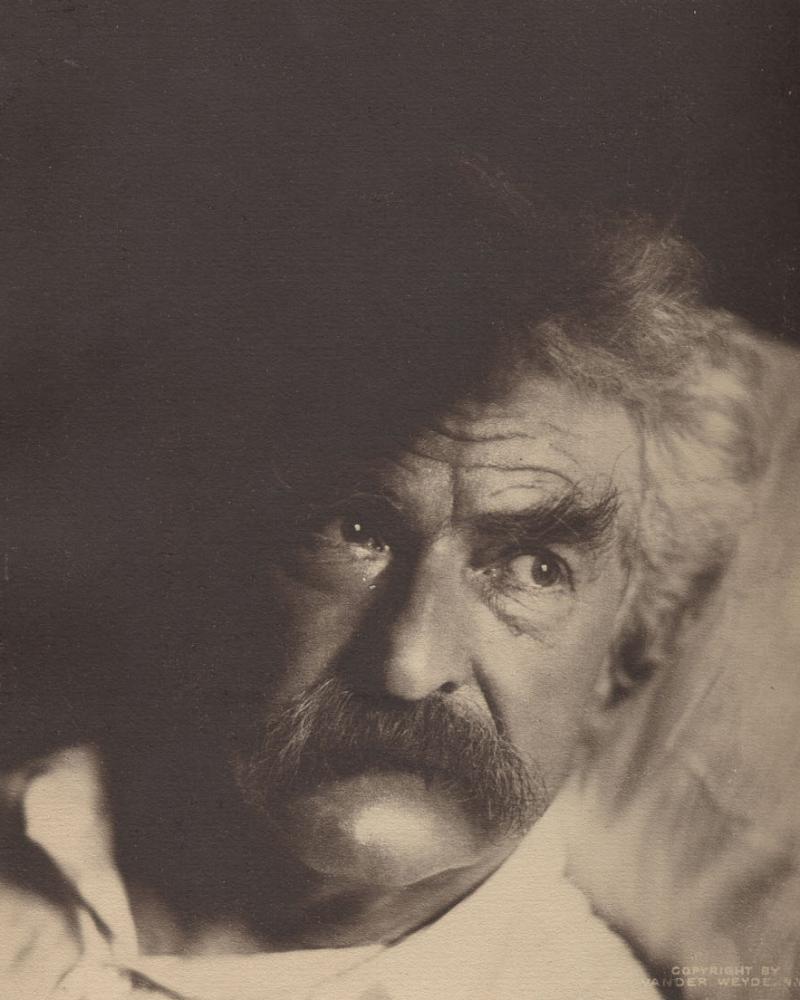

Samuel Clemens as a teenage printer in Hannibal, Missouri, 1850.

Samuel Clemens as a teenage printer in Hannibal, Missouri, 1850.

Mark Twain demanded that his autobiography not be published in its entirety until 100 years after his death because he feared that much of it was too incendiary.

Now, exactly a century later, the first authoritative volume has arrived, after decades of painstaking scholarship involving tens of thousands of documents -- and after decades of NEH support. Readers can finally see the unexpurgated version of Twain’s views on Christianity, government, human nature and scores of his contemporaries from Ulysses S. Grant and Horace Greeley to Booker T. Washington and the Rockefellers.

At over 700 copiously annotated pages and a list price of $34.95, the Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1 became a runaway best-seller when it was published in November of 2010.

But thanks to funding by NEH and other contributors, anyone can read it for free at the Web site of the Mark Twain Papers & Project, housed at the University of California at Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

Readers expecting a conventional linear chronology will be surprised. Twain struggled for 30 years against the constraints of a cradle-to-grave narrative. By 1906, when he began dictating large portions of the Autobiography, “he had finally liberated himself from that,” says Robert Hirst, General Editor of the Mark Twain Papers. “It took him a long time to get to the final form. And the final form is this: I’m going to talk about whatever I want to talk about, I’m going to change the subject whenever I lose the least bit of interest, and go to some other topic.”

However, the original documents – a welter of fragments, false starts, revisions and variations – are “to a degree puzzling and confusing,” Hirst explains. That is why it took decades before it became clear exactly what Twain had in mind. “In fact, we thought until three years ago that this whole manuscript was a kind of incomplete set of drafts. But that’s wrong.The editors who worked with me out in Berkeley are the ones who figured out that Twain had actually finished it. He knew exactly how he wanted to begin it, exactly what he wanted in it, and exactly what he didn’t want in it.

“From our point of view,” Hirst says, “it’s like discovering all of a sudden that you’ve been sitting on Mark Twain’s last major literary work and you didn’t know it!”

The result has delighted many reviewers. “Mark Twain is his own greatest character in this brilliant self-portrait,” said Publishers Weekly. "Dip into the first enormous volume …” from this seemingly well-known figure in American history, The New York Times review said, and “Twain will begin to seem strange again, alluring and still astonishing, but less sure-footed, and at times both puzzled and puzzling in ways that still resonate with us, though not the ways we might expect." In short, the Wall Street Journal observed, “every word beguiles.”

For more information, see the Mark Twain Project Web site and the Mark Twain Papers & Project Web site.