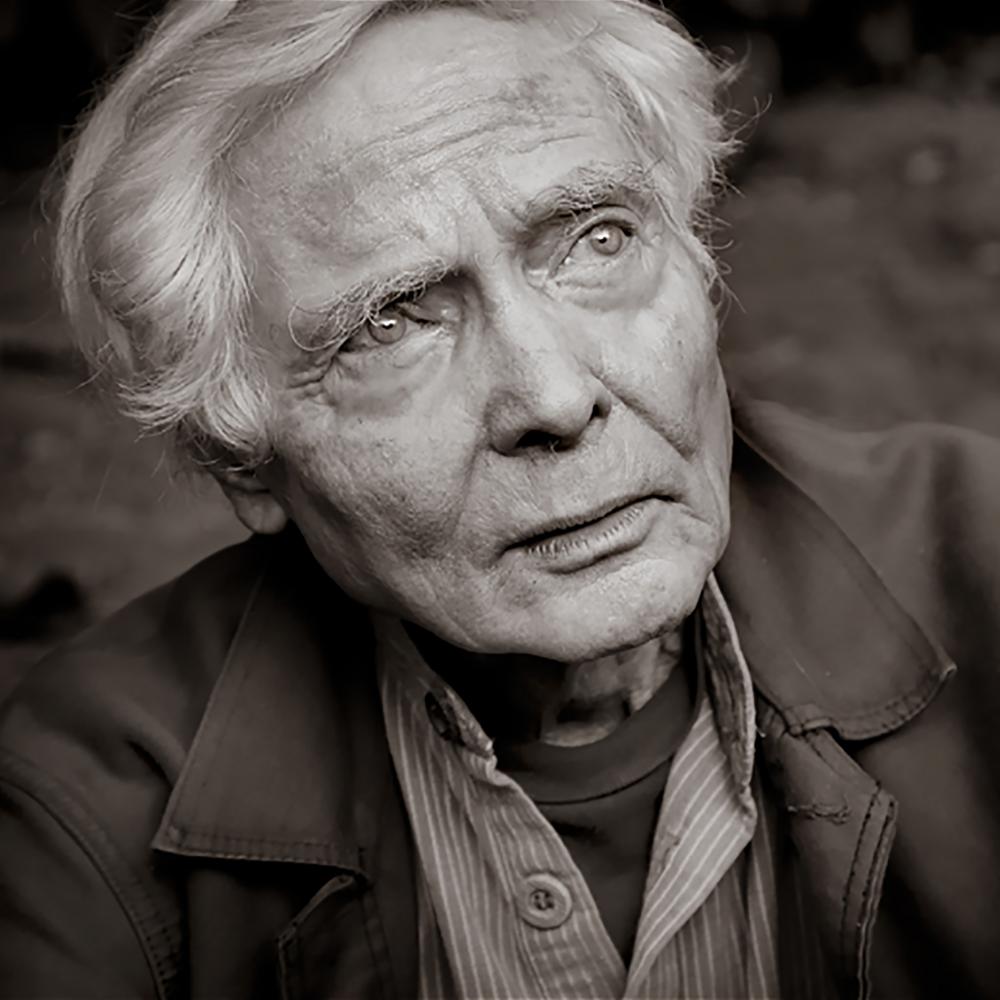

W. S. Merwin, who twice won the Pulitzer Prize, first tried his hand at poetry as a child. Growing up in Union City, New Jersey, he was moved to bring pen to paper after hearing his father, a Presbyterian minister, read from the King James Bible at church. Young William realized that there was a “distant connection” between that kind of heightened language and poetry. “And that’s what I wanted to do, to write poetry. And the more I did it, the more I wanted to do it.”

Merwin developed an impersonal formalist style, but in time his poems trended toward a freer and more lyrical approach. His work, steeped in legend, the classics, and the Bible, is also anchored in the present, marked, above all, by a vigilance for all living things. Although he has been an angry poet at times, he has avoided bitterness by learning to transform his rage into art. Transformation is the key to understanding his work, as the hallmark of his poetry since the early sixties has been his mastery of “the turn,” the moment in a poem where an idea turns, often with a surprise, into something else.

His first books of poetry were marked by objectivity, elegance, and formal constraints. He wrote in meter and tried his hand at a variety of poetic forms, including the sestina. One critic observed that his first book, A Mask for Janus (1952), “exhibits a young musician trying out his instrument.” His diction was elaborate, using such terms as “anabasis” (a difficult military retreat), “koré” (an ancient Greek statue of a woman), “saeculum” (an Etruscan word for a specific period of time, usually the length of a generation), and “penates” (household gods in Roman times). To understand the volume’s first two poems, “Anabasis,” parts I and II, it helps to have read Xenophon. History-laden words, as in the poetry of his mentor Ezra Pound, had for Merwin a creative force all their own.

But erudition always vied with living things for Merwin’s attention. Plants, trees, and animals have been of particular interest. In the poem “Birds Waking,” a serene early-morning scene yields to an avian chaos:

And from the hill chestnuts and the park trees

There was such a clamor rose as the birds woke,

Such uncontainable tempest of whirled

Singing flung upward and upward into the new light,

Increasing still as the birds themselves rose

From the black trees and whirled in a rising cloud,

Flakes and waterspouts and hurled seas and continents of

them

Rising, dissolving, streamering out, always

Louder and louder singing, shrieking, laughing.

Sometimes one would break from the cloud but from the song never,

And would beat past my ear dinning his deafening note.

I thought I had never known the wind

Of joy to be so shrill, so unanswerable,

With such clouds of winged song at its disposal, . . .

Two lines later the poem abruptly turns to the “many ways we may end” and concludes with an apocalypse: “Let the great globe well up and dissolve like its last birds / With the bursting roar and uprush of song!” “Birds Waking,” an angry poem indeed, was written around the time Merwin joined a mass protest march on Easter weekend 1960, beginning at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment in Berkshire and coming to an end 52 miles later in London.

The seeds of Merwin’s fascination with the natural world and his commitment to ecology and the environment were planted much earlier. Born in 1927 in New York City, Merwin grew up in New Jersey and Scranton, Pennsylvania. One early memory was of men arriving to cut down tree limbs near the family home, filling the boy with rage. He tore out of the house and ran up to the tree cutters, hitting and yelling at them until they left.

Always a talented student, Merwin skipped grades and graduated high school early. In 1944, he took the college entrance exams and won a scholarship to Princeton, where he majored in English. At Princeton, he became friends with poet Galway Kinnell, whose “sense of wonder and exaltation” he would embrace and make his own. It was at Princeton, too, that he met American poet John Berryman, who told him, “I think you should get down in a corner on your knees and pray to the Muse, and I mean that literally.” What Merwin did do was go horseback riding at night, spend much time in the bookstore, fall in love with the secretary of the physics department, Dorothy Jeanne Ferry, and marry her in 1946, with his father officiating.

Many of Merwin’s contemporaries in the 1950s—Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, and W. D. Snodgrass—were confessional poets. The “I” in the work of a confessional poet stands for their own experiences in a specific time and place. Even when not using the pronoun “I,” a poet such as Berryman could still write about personal experiences simply by using, as Berryman did in Dream Songs, an alter ego. Merwin, however, was anything but confessional, opting rather for what W. H. Auden called in his preface to A Mask for Janus, a “concern for the traditional conceptions of Western culture as expressed in its myths.”

The young poet possessed almost careless good looks. He cut his own hair and bought his clothes from thrift stores to save money and, in his mind, retain his freedom. His locks tumbled over his ears and down his neck. He dressed tastefully in sturdy garments. Photographs from the era started recording the type of freer-style poet he would become. In his personal life, too, there would be fewer constraints. The marriage with Dorothy would dissolve, and a woman he had first met at the Majorcan home of British poet Robert Graves—playwright Dido Milroy—became his next love interest. While living in London, Merwin collaborated with Dido on a play produced by the Arts Theatre.

In 1956, Merwin became playwright-in-residence at Poets’ Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He moved from London to Boston with Dido, and met Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, and Robert Lowell. Merwin’s work in progress at the time was The Drunk in the Furnace (1960), which included poems that Lowell read and admired. During the residency at Poets’ Theatre, Merwin wrote a play, Favor Island, about shipwrecked sailors, which was later produced at the theater, and after he completed his residency there he returned to England with Dido.

Along with themes of myth and legend, themes of family and society anchored an increasing number of Merwin’s poems by the late fifties and early sixties. One is the title poem, “The Drunk in the Furnace,” which powerfully depicts the milieu of Merwin’s childhood though focused on a most particular setting, the town dump:

For a good decade

The furnace stood in the naked gully, fireless

And vacant as any hat. Then when it was

No more to them than a hulking black fossil

To erode with the rest of the junk-hill

By the poisonous creek, and rapidly to be added

To their ignorance,

They were afterwards astonished

To confirm, one morning, a twist of smoke, like a pale

Resurrection, staggering out of its chewed hole,

And to remark then other tokens that someone,

Cosily bolted behind the eyeholed iron

Door of the drafty burner, had there established

His bad castle.

Where he gets his spirits

It’s a mystery. But the stuff keeps him musical:

Hammer-and-anviling with poker and bottle

To his jugged bellowings, till the last groaning clang

As he collapses onto the rioting

Springs of a litter of car seats ranged on the grates,

To sleep like an iron pig.

In their tar-paper church

On a text about stoke holes that are sated never

Their Reverend lingers. They nod and hate trespassers.

When the furnace wakes, though, all afternoon

Their witless offspring flock like piped rats to its siren

Crescendo, and agape on the crumbling ridge

Stand in a row and learn.

The poem—one that holds significance not only for its powerful evocation of a sense of place, but also for the transition it represents in Merwin’s work—suggests both the personal experience expressed by the confessional poets and the objectivity so admired by the formalists. Town dumps in small-town, early- to mid-twentieth-century America had mythic power all their own. They were less an eyesore than a local necessity and often accommodated the rootless and the marginal. In this case, is the setting the Scranton of Merwin’s childhood? It seems likely. And in the last line of the second stanza, who could read “bad” in this context and not be struck by a note from the American vernacular—“bad” as in the phrase “in your face”? In the poem’s second and final two stanzas, we hear the “jugged bellowings” and a “groaning clang” that are overheard, too, nearby in the “tar-paper church” as the congregation’s “witless offspring flock liked piped rats” to listen to the “siren crescendo.” Merwin’s father’s Presbyterian church in Scranton was no tar-paper affair, but, rather, a solid edifice of stone. The continuity cannot be overlooked, however, regarding the boy Merwin was, writing poetry inspired by the Bible and the adult looking back. How could a reader not see Merwin’s father in the poem’s Reverend, who, “lingers over a text,” as the rest in church “nod and hate trespassers”?

After Merwin returned to England in 1957, he met or became friends with poets Louis MacNeice and Henry Reed, as well as actor John Whiting. Hughes and Plath would also move to England, but by 1963, the year of Plath’s suicide, Merwin was back in the United States, living in New York City’s Lower East Side. In “Home for Thanksgiving,” then, a sometimes surreal portrait comes into view of his homeland:

I bring myself back from the streets that open like long

Silent laughs, and the others

Spilled into the way of rivers breaking up, littered with

words,

Crossed by cats and that sort of thing,

From the knowing wires and the aimed windows,

Well this is nice, on the third floor, in back of the billboard

Which says Now Improved and I know what they mean,

I thread my way in and sew myself in like money.

The speaker goes on to muse over women loved and abandoned, “Vera with / The eau-de-cologne and the small fat dog named Joy”; “Gladys with her earrings, cooking and watery arms”; and “the one / With the limp and the fancy sheets.” The return—echoing the prodigal son’s—is filled with mixed emotions and some regret, but, even so, the poet (still not quite confessional) cries,

Oh misery, misery, misery,

You fit me from head to foot like a good grade suit of longies

Which I have worn for years and never want to take off.

I did the right thing after all.

Confessional poet or not, the former activist Merwin withdrew from the world, into depths sometimes known as la France profonde. This history-laden phrase has often been translated as “authentic” or “true France,” as in the Gallic landscape where, in the early sixties, Merwin sought and found a tangible link to the land, the imagination, and the ancient past.

During his time living in a half-ruined farmhouse in Dordogne, in southwest France, Merwin published The Moving Target (1963) and worked on poems forThe Lice (1967) and The Carrier of Ladders (1970) “By the end of the poems in The Moving Target,” he writes, “I had relinquished punctuation along with several other structural conventions, a move that evolved from my growing sense that punctuation alluded to and assumed an allegiance to the rational protocol of written language, and of prose in particular. I had come to feel that it stapled poems to the page. Whereas I wanted the poems to evoke the spoken language, and wanted the hearing of them to be essential to taking them in.”

In 1968, between the publication of The Lice and The Carrier of Ladders, Merwin’s second marriage, to Dido, broke up. During the separation and even after their divorce in 1978, Dido continued living in the French farmhouse till her death in 1990, when Merwin then resumed residence there for a while, before moving back to Hawaii. He turned to gardening as an avocation and learned from an Englishman living nearby the rudiments of organic farming, thus deepening his ongoing love affair with caring for the land.

While Merwin’s career sparks comparisons and contrasts with many twentieth-century poets, it also calls to mind two nineteenth-century American writers: Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau. Like Whitman, Merwin can sometimes be a cataloger of work and the tools of a trade, but his is often a more somber reaction to Whitmanian exuberance. In the 1956 poem “The Fishermen,” Merwin starts out creating an upbeat, or at least positive-tending portrait:

When you think how big their feet are in black rubber

And it slippery underfoot always, it is clever

How they thread and manage among the sprawled nets, lines,

Hooks, spidery cages with small entrances.

Then comes the turn, as the poem shifts to a minor key, observing laconically:

But they are used to it. We do not know their names.

They know our needs, and live by them, lending them wiles

And beguilements we could never have fashioned for them;

They carry the ends of our hungers out to drop them

To wait swaying in a dark place we could never have chosen.

The poem’s stark conclusion establishes a distance between those who merely consume and those who provide:

By motions we have never learned they feed us.

We lay wreaths on the sea when it has drowned them.

Thoreau, by contrast, with his belief that “in wildness is the preservation of the world,” is much closer to Merwin’s worldview, as poems from The Vixen (1996) can demonstrate. From "The Vixen," the line “you no longer go out like a flame at the sight of me,” reveals a Thoreauvian love for living near wildness and the patience required for experiencing it. Then, the next line, fully expressed, is an ecological stance, one recognizing the vulnerability of the wild: “you are still warmer than the moonlight gleaming on you.” An earlier Merwin would have been angry to the point of not writing at all, but the Merwin that evolved into the nineties was able to fine-tune his anger and use it. “Let me catch sight of you again going over the wall,” he writes, “before the garden is extinct.”

From his earliest years, watching the busy river traffic on the Hudson from the second story of his family’s house in Union City, to the residence on a former pineapple plantation the island of Maui he shared with his third wife, Paula (now deceased), Merwin has always sought ways to write about landscape and the imagination. It’s what drove him from Lower Manhattan to southwest France and from Boston to England, and in part what impelled him to move to Hawaii. Merwin keeps writing poetry nearly every day, angry on behalf of nature and still vigilant, “Even though,” he says in the poem “Rain Light,” “the whole world is burning.”

This article was updated on January 31, 2018, to reflect the fact that Merwin's third wife, Paula, died in March 2017. An additional update was made on February 8 to mention of the poets Merwin knew when he was in London in 1957.