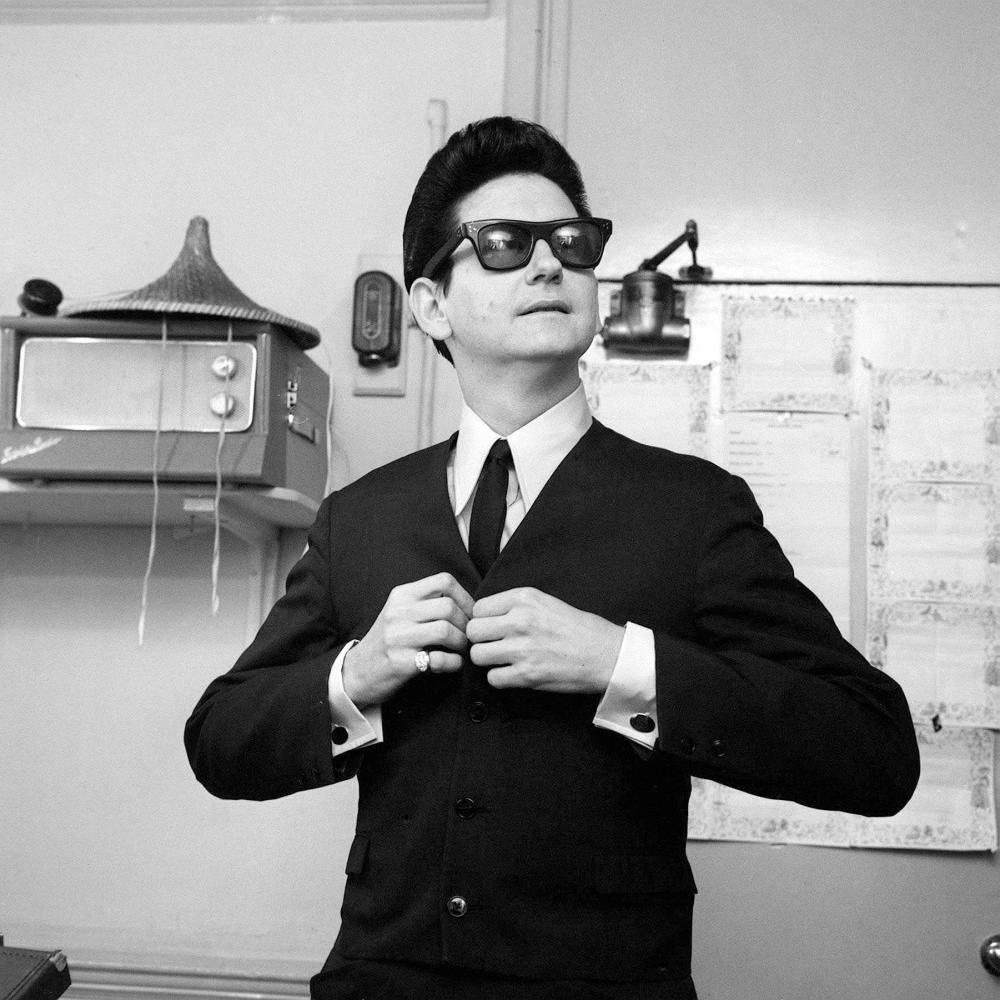

Roy Orbison was a rock ’n’ roll enigma. He possessed neither Elvis’s gyrating pelvis nor Jerry Lee Lewis’s pound-the-piano machismo. Teenage girls didn’t scream for him; teenage boys weren’t jealous. In the early 1960s, he recorded 19 Top 40 hits and toured with the Beatles, yet he was not a media sensation. Nothing in his persona resembled danger like other early rock stars—no hyperactive stage antics, no threats to public decency, no sultry good looks. Instead, Orbison would walk on stage, dressed all in black, with jet black hair, dark sunglasses, a black guitar, looking more like a shadow than a rocker. He would stand perfectly still in the spotlight, strum his guitar, and start singing.

What came out was a voice like nothing heard on the radio at the time. An effortless three-octave range that was so powerful, yet so vulnerable, it shattered hearts. It’s said that Dwight Yoakam described Orbison’s voice as “the cry of an angel falling backward through an open window.” Even in an upbeat song like “Oh, Pretty Woman” —a song where he gets the girl—his melancholy tone makes us feel the anxiety, fear, and insecurity of waiting for her to turn his way.

“Roy’s extreme development of those kinds of emotions and the intensity with which he expressed them certainly went against the grain of the kind of macho, confident, masculine display that characterized so much of mainstream rock ’n’ roll,” says Orbison biographer Peter Lehman. “The songs were also, as in ‘Only the Lonely,’ first-person narrations. So he begins to build a persona from song to song about himself as this suffering male character who experiences these intense emotions linked to extreme loneliness, crying, suffering, and pain, at a level of intensity that was not the norm for men at that point of time in the early ’60s.”

Lehman, along with Orbison’s family, friends, and collaborators such as T Bone Burnett, Marianne Faithfull, and Jeff Lynne are all part of a documentary, Roy Orbison: One of the Lonely Ones, which had its U.S. premiere in Tempe last spring with support from Arizona Humanities. Following the screening, a discussion took place with filmmaker Jeremy Marre and Lehman, who is the director of the Center for Film, Media and Popular Culture at Arizona State University.

After a string of Top 40 hits from 1960 to 1964, nine of which made the Top 10, Orbison jumped labels from Monument to MGM Records. A prolific songwriter and performer, Orbison tried to recover the magic of his Monument years but with little success. During that time, he also suffered personal tragedies, including the death of his wife, Claudette, in a motorcycle accident in 1966 and the deaths of two of his children in a house fire in 1968 while he was touring in England. His voice was largely overlooked during this dark period and continued to be ignored in America throughout the 1970s. After more than a decade in the wilderness, all that would change. American artists began covering his songs with great success, including “Blue Bayou” by Linda Ronstadt, “Oh, Pretty Woman” by Van Halen, and “Crying” by Don McLean.

According to Lehman, three events marked his return to the public stage: David Lynch’s startling use of “In Dreams” in the movie Blue Velvet in 1986, Bruce Springsteen’s emotional speech when Orbison was elected to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, and the TV concert Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night in 1988 that had Orbison front and center with a backup band that included Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, T Bone Burnett, Jackson Browne, J. D. Souther, and Elvis Presley’s TCB band with James Burton on guitar, and backup singers Bonnie Raitt, Jennifer Warnes, and k.d. lang, with whom Orbison would share a Grammy that year for their duet of “Crying.” Orbison said of his triumphant return, “It was like everyone was starting up my career without me. And my life, again, climbed mountains.”

In 1988, he joined the band the Traveling Wilburys which included George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, and Jeff Lynne. With the release of the Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1, Orbison once again hit the Top 10, the first time since 1964. Riding high, Orbison recorded a major solo comeback album, Mystery Girl, which was scheduled for release in January 1989. On December 6, 1988, Orbison died of a heart attack at his mother’s home in Hendersonville, Tennessee; he was 52 years old.

Lehman says, “Bruce Springsteen wisely observed, ‘Everyone knows no one sings like Roy Orbison.’ Rather than inspiring other singers to copy him or sound like him, he inspired them to be different and to find their own voices.”

In Orbison’s own words, which come near the end of the documentary, he reflects on the ups and downs of his musical career. “You set out to beat the world, and you get beat up a little. I knocked the tops off mountains, but I also filled in the valleys.”