Thanks to “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” his creepy tale about an ungainly schoolteacher who vanishes mysteriously in the woods, Washington Irving is perhaps best known to modern readers as an author to read on Halloween.

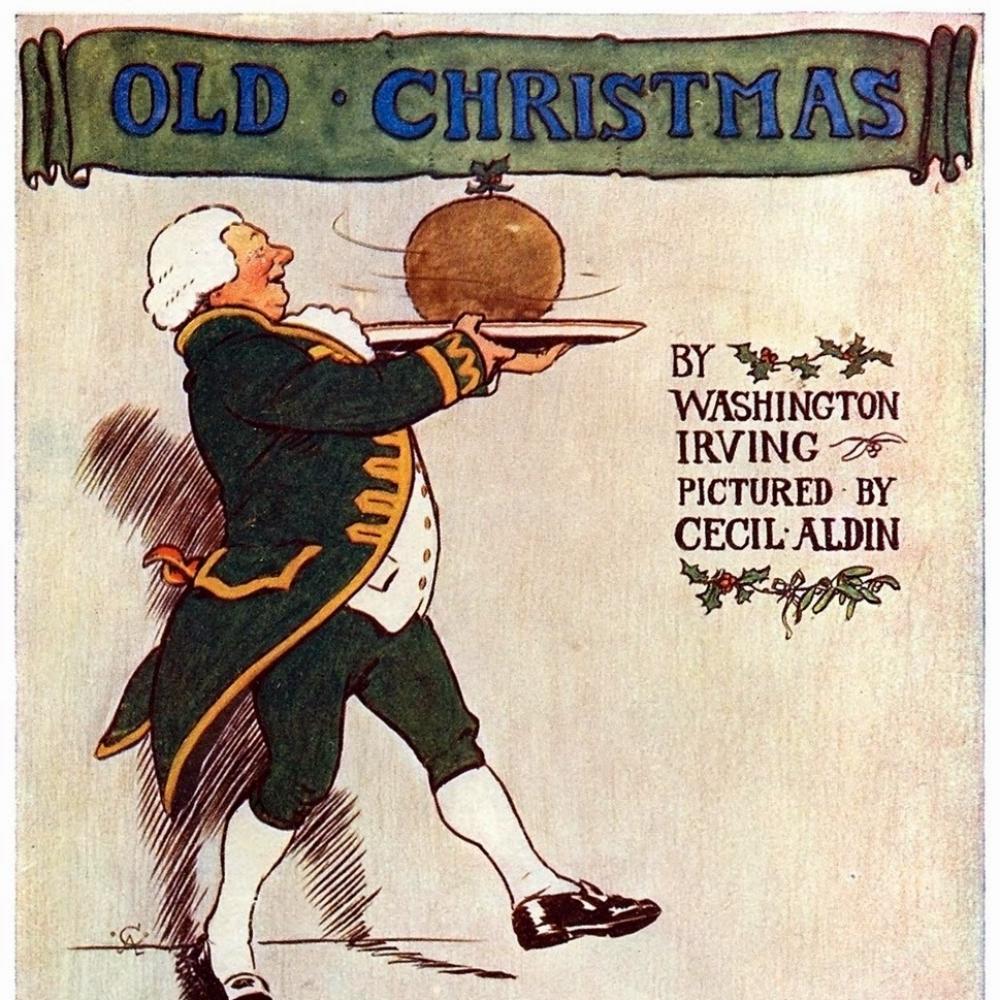

But Irving wrote much more about yuletide—so widely and imaginatively, in fact, that he’s often credited with creating Christmas in America as we know it.

“He did not ‘invent’ the holiday,” biographer Andrew Burstein notes, “but he did all he could to make minor customs into major customs—to make them enriching signs of family and social togetherness.”

Among Irving’s biggest contributions to Christmas in America was his promotion of St. Nicholas as a beloved character, laying the groundwork for the figure we’d eventually embrace as Santa Claus.

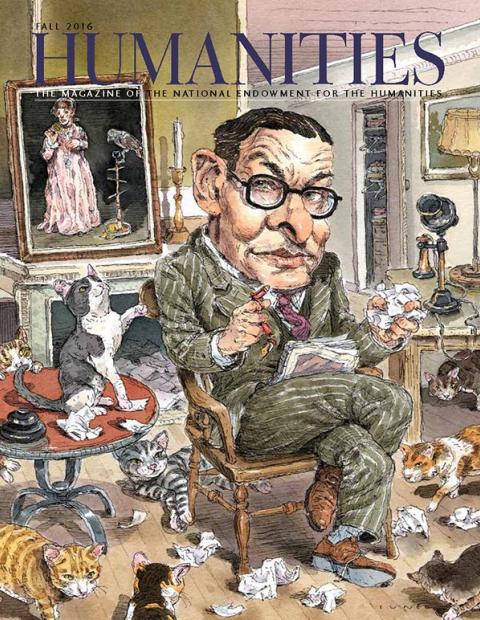

Irving (1783–1859) was the subject of a 2014 Humanities profile because of his trip through the American West—an unlikely and sometimes comic odyssey for a man who was more at home in his native New York City and the great capitals of Europe.

Gotham, in fact, was the subject that established Irving’s fame in 1809, when his A History of New York became a publishing sensation. The book was conceived as a parody of Samuel L. Mitchill’s The Picture of New-York; or the Traveller’s Guide through the Commercial Metropolis of the United States.

Mitchill, a Columbia medical professor and U.S. senator, seemed to know everything about everything, and Irving poked fun at Mitchill’s know-it-all sensibility with his fictional account of Manhattan, which includes some tall tales about its origins. Among Irving’s yarns was a story about the shipwreck of a Dutch scouting party on Manhattan, where one of its members receives a vision in which “good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children.” Nicholas tells the Dutch to settle on the island—Saint Nick, in a sense, becoming the founding father of the most famous city in America.

Irving’s affection for Saint Nicholas proved durable. In 1835, he helped found the Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York, serving as its secretary until 1841. Beyond his interest in Nicholas, Irving advanced Christmas as the festive pageant of presents and feasting that now dominates the American winter calendar.

He had traveled to England in 1815, where various personal and professional interests kept him abroad until 1832. The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which greeted American readers in 1819, contained a smattering of essays and short stories, including the iconic “Sleepy Hollow,” but its pieces on yuletide helped revive interest in the holiday. “While a number of other stories in The Sketch Book were better known, none would have a greater impact on American culture than these four Christmas essays,” writes biographer Brian Jay Jones.

Irving wrote with fondness of old English Christmases, with their dinners and dancing and singing, their decorations and blazing fires, their air of good cheer. “Amidst the general call to happiness, the bustle of the spirits, and stir of the affections, which prevail at this period,” he asked, “what bosom can remain insensible?”

Back in his homeland, Irving’s homage to the holiday resonated with the public. “Charles Dickens later fine-tuned the Christmas story,” Jones argues, “but Irving had laid the foundation. Americans embraced Irving’s vision of Christmas as their own, marking the revival of a holiday that had been banned in parts of the country for the excessive drinking and fighting it spurred in the populace.”

As Burstein points out, “Irving dressed up an idea that had been floating around.”

Until the end of his life, or so it seems, Irving saw Christmas not only as an indulgence, but a spiritual necessity. “He who can turn churlishly away from contemplating the felicity of his fellow beings,” he wrote, “and can sit down darkling and repining in his loneliness when all around is joyful, may have his moments of strong excitement and selfish gratification, but he wants the genial and social sympathies which constitute the charm of a merry Christmas.”