The new PBS documentary, The Great Famine, will finally acquaint American television viewers with an important, yet little-known episode in the history of American relations with the former Soviet Union. The film dramatically documents the story of the American Relief Administration’s (ARA) aid to starving Russians in the early 1920s, and shows how this magnanimous effort became an early indicator of the tensions that would characterize the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union, until the latter’s collapse at the end of the twentieth century.

Written and produced by Austin Hoyt, coproduced by Melissa S. Martin and edited by Jon Neuburger, the film covers the events during and immediately after the Russian Civil War. Fighting between the Bolsheviks and their White Russian opponents resulted in a collapse of the economy, producing both scarcity in the cities and impoverishment in the countryside. Mass requisitions of grain by the Bolsheviks also meant that the peasants could not feed themselves. A severe drought in 1921 compounded the situation, culminating in a famine that the filmmakers declare was the worst natural disaster to strike Europe since the Black Death in the Middle Ages.

Based on the thorough scholarly book by Bertrand M. Patenaude, The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921 (Stanford University Press, 2002), the film powerfully conveys through photographs, films, and recreations, the depth of the crisis and the importance of the American response to the suffering--a response that saved millions of lives, particularly of young children. The film successfully dramatizes the story with first-rate reenactments of critical episodes, artfully delivered by actors in period costume. In most documentaries, this technique falls flat; here, the producers limit the use to key events, and integrate the actors into the story, combining their reenactments with the testimony of scholars as well as descendants of many of the original figures discussed in the film.

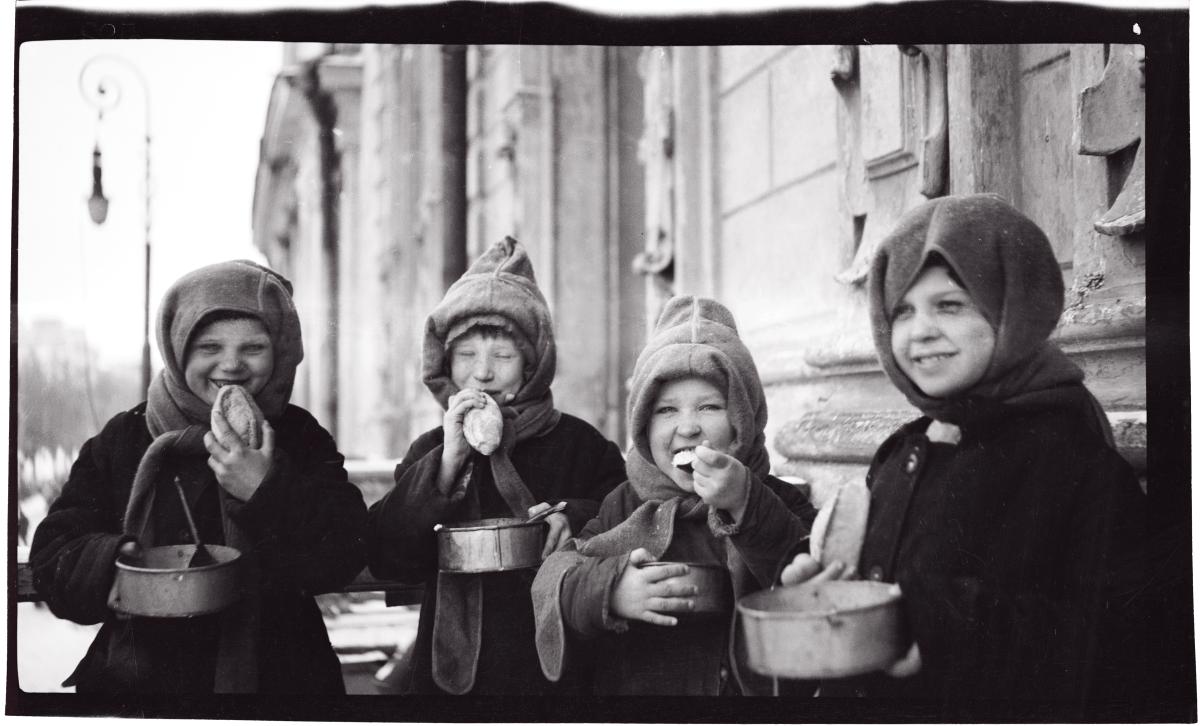

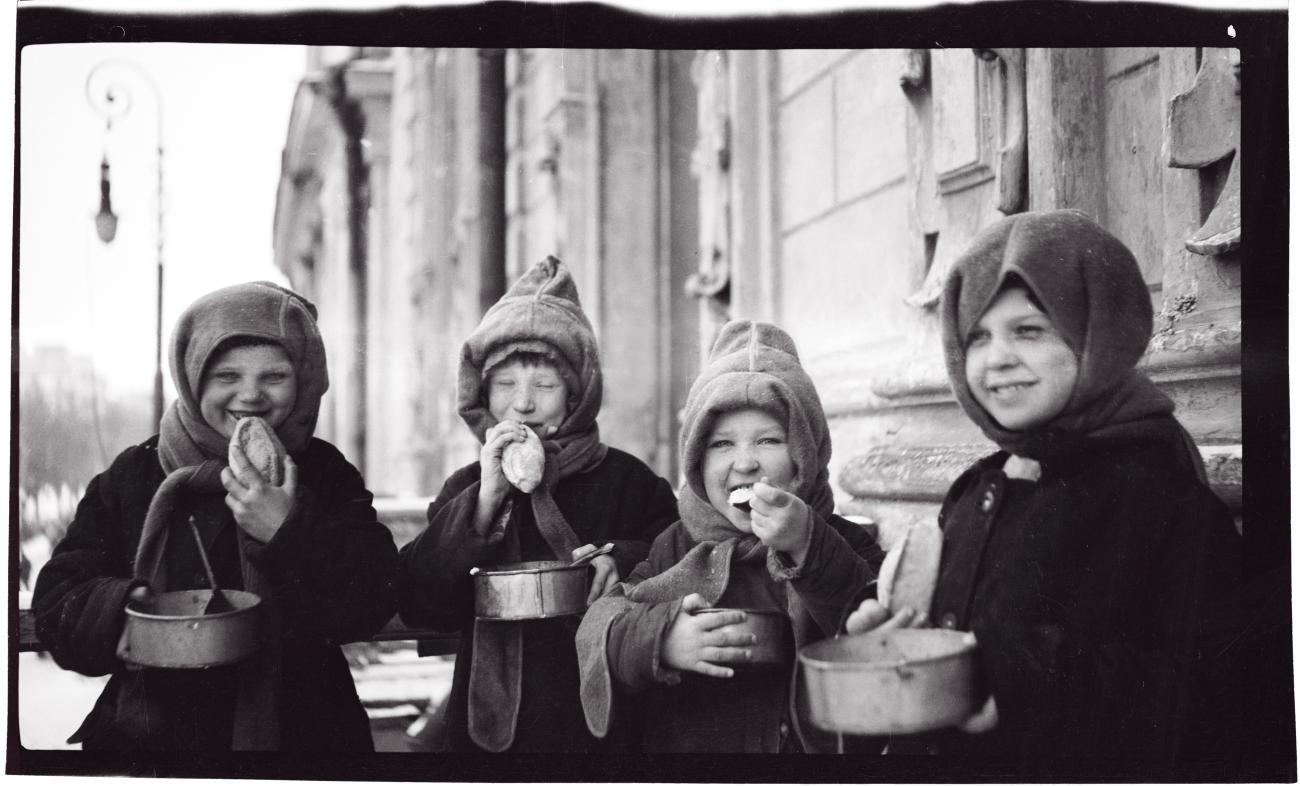

Before American aid arrived, an estimated five million Russians had already died of starvation. Once aid started getting to the Russian citizens, some eleven million people were fed each day out of nineteen thousand kitchens. Bread, which had disappeared because of the collapse of grain production, was supplied by ARA-supported bakeries. Children were fed soup, condensed milk, as well as meals that survivors shown in the film remember to this day. It was to be the largest relief effort in the world up to that point, surpassing even the relief work during World War I.

Some of the most interesting stories in the film focus on the ARA workers, who tended to be well-educated World War I veterans in their twenties. Will Shafroth fits this profile. His father had been the governor of Colorado, and he had graduated from the University of Michigan in 1914, earning a law degree from the University of California in 1916. The film opens with a dramatic excerpt from his diary. When the twenty-nine-year-old Shafroth arrived in Samara on the Volga, he found men digging mass graves for their neighbors whom they expected to die soon from starvation. They explained to him that they had to dig the graves while they still had the strength, knowing that they were probably digging their own graves as well.

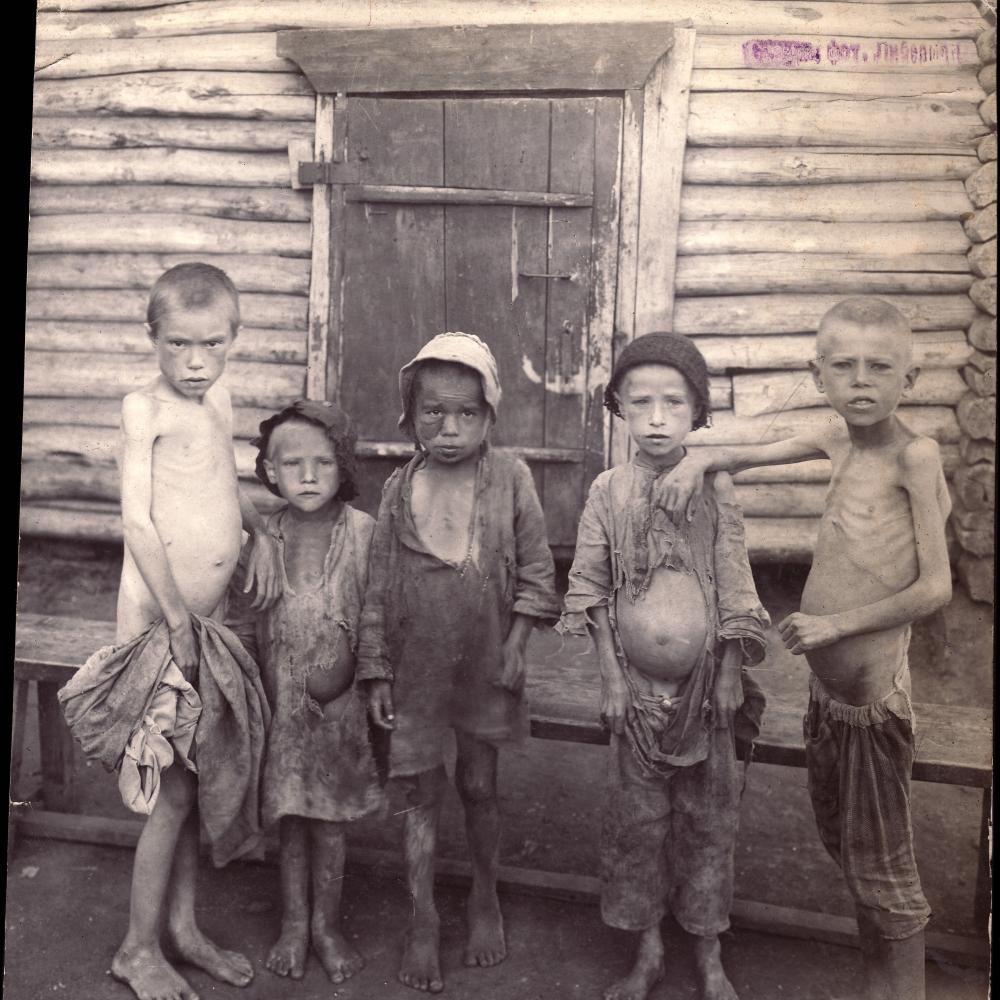

This scene was bad enough, but nothing had prepared Shafroth for the skeletal children he met, with distended stomachs known as “hunger bellies,” with legs that looked like toothpicks and faces that made them appear to be old men and women. When he visited typical orphanages, the scenes of the dying children filled him with horror. In one, 283 children were living in three rooms, where they all slept on the floor. When these pathetic children sang for him it was so painful to watch he had to turn away. Walter Bell, another American relief worker, found people eating leaves mixed with bark and clay. There were reports of people digging up corpses to eat, butchers selling human flesh, and parents actually killing and then consuming their older starving children in order to feed their younger children and infants. Press reports in the United States reported, mistakenly, that Shafroth himself had been murdered and then eaten.

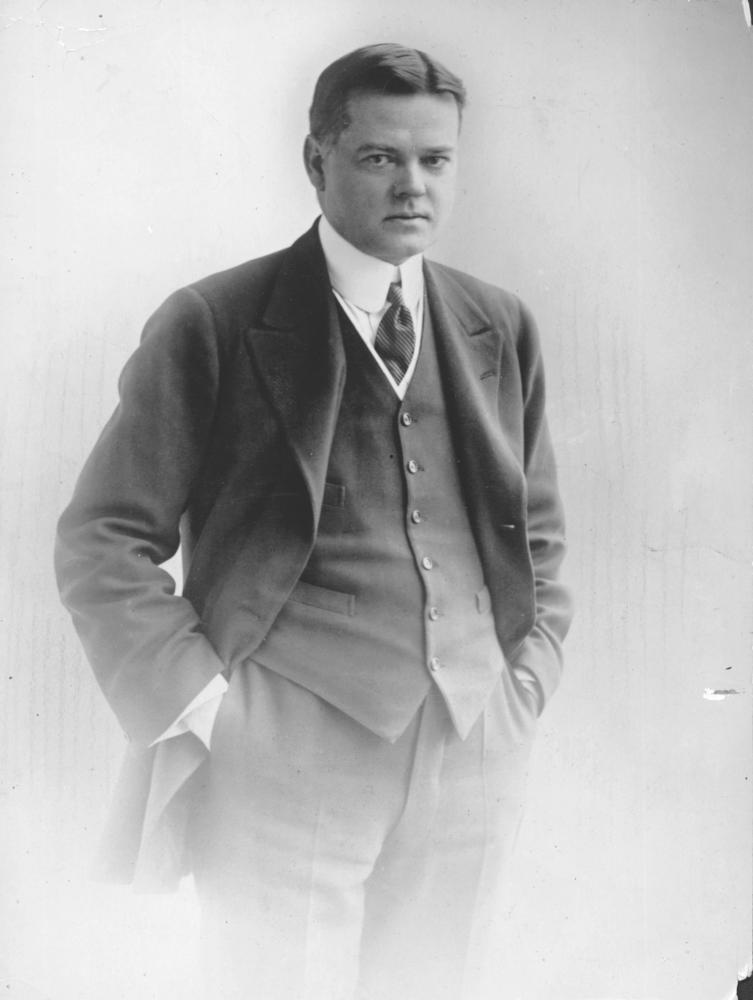

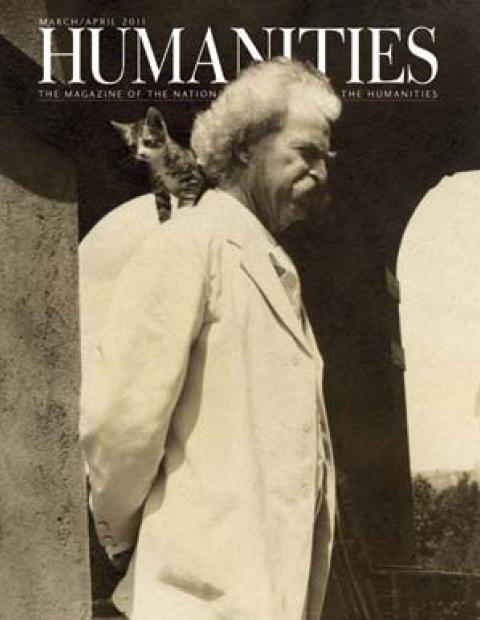

The American relief effort got its start in July 1921, when famed Soviet writer Maxim Gorky issued a plea to Americans and Europeans for help to save millions of Russian lives by providing food and medicine. Gorky’s appeal did not mention the Revolution or the Soviet government, emphasizing instead the plight of the Russian people. President Warren Harding’s newly appointed secretary of commerce, Herbert Hoover, read Gorky’s statement in the newspaper. A former international mining engineer who had experience moving men and material, Hoover had been America’s chief WWI relief administrator for Europe and head of the ARA. Called the “master of emergencies,” Hoover was already credited with saving more lives than anyone throughout history.

Viewers whose image of Hoover is that of a skinflint who precipitated and prolonged the Great Depression and who did little to help suffering Americans, will be stunned to find that in the 1920s he was known as “The Great Humanitarian.” Hoover had orchestrated the vast war relief program in Europe, particularly bringing food relief to millions of French and Belgian citizens during the wartime occupation. Then, after the Armistice, Hoover continued to fund and administer food relief for the needy children of war-torn Europe. Now he believed it was his and America’s duty to answer Gorky’s desperate call, and to once again mount a massive relief effort to save the Russian people, whose future lay in doubt.

As a confirmed opponent of the Bolsheviks, Hoover used the occasion to play a dual game. He looked to create goodwill for the United States, while striking a blow against the new Bolshevik regime and its credo of international Communist revolution. There was also an opportunity to help American farmers who, after WWI, were suffering from deflated prices and a precipitous drop in the value of farmland. The Russian crisis was a chance to expand America’s agricultural exports and thus help American tillers of the land unload their huge surplus of corn and other produce.

The first American ships arrived in Russia on September 1, 1921, carrying seven hundred tons of food, mostly corn, which was used to feed children in the cities. But reports from ARA supervisors quickly convinced Hoover that the program needed to be greatly expanded and that adults also needed to be fed. He proposed to Congress that $20 million be appropriated to buy excess corn and wheat seed from American farmers. Although Hoover had President Harding’s support, he knew it would be difficult to obtain the approval of Congress for the amount of aid needed. Gaining the support of the powerful Congressional farm bloc was crucial. To Hoover’s credit, he insisted that part of the relief be made up of wheat seed to be planted, ensuring that the famine did not continue for another year, and that at the end of the aid, Russian farmers could again be self-sufficient.

Many were skeptical that Hoover, a known anti-Bolshevik, was the man to administer Russian relief. How, critics asked, would he be able to work with the very regime he detested? Opponents on the Left feared the aid would be a subterfuge for a covert anti-Bolshevik program, while those on the Right believed that giving help to the Russian people would inadvertently help the Soviet regime to survive. Hoover, it seemed, was caught in the middle.

It was indeed accurate to view Hoover as a man who wanted to “stem the tide of Bolshevism.” The way he hoped that could be accomplished was to use food as a weapon—not as Lenin and the Bolsheviks thought, by withholding it unless the Soviet government bent to the U.S.’s will—but rather, by gaining control of the food supply within Bolshevik Russia so that the credit for relief would be given to the United States and to the American people. By contrast, he hoped, the American model of efficiency, competence, and humanitarianism would turn the Russians away from the Bolsheviks, who had helped produce the crisis and who were helpless to remedy it.

In one sense, Hoover was successful; people interviewed in the film remembered that their parents gave the name “America” to the life-giving food they received. One Russian recalls how his grandmother and parents told him never to forget how they were saved by the American people. Another relates how his own family escaped starvation, and, as a result, he went on to become one of the most famous ballet dancers in the Soviet Union.

Hoover indeed had a political agenda, but for him this presented no moral conflict. He, Woodrow Wilson, and Warren Harding all viewed Bolshevism as a utopian and fanatical movement that would end up causing great distress for the common people. Thus, for Hoover, to oppose and to fight Bolshevism was the very heart of humanitarianism.

Finally, an agreement was reached between the American government and the Soviets. The Americans, ostensibly steering clear of politics, vowed to feed the Russian population impartially, while the Soviets agreed to allow the ARA the freedom to organize its relief efforts. Prolonged negotiations at Riga led to this highly controversial settlement, which negotiators on both sides worried contained too many loopholes. In the end, both sides fudged the agreement. The Soviet leaders, including Lenin, still suspected that espionage was the real aim of the ARA workers, and the Bolsheviks continually tried to gain control of administering the food supplies for the regime’s benefit. The ARA workers complained accurately about constant interference by Cheka, the notorious secret police that was the predecessor of the NKVD and KGB.

The ARA began its work by dividing Russia into ten districts with about nine million people each. ARA supervisors were charged with finding locations to set up warehouses and then identifying starving adults who needed relief. The aid also became a way to hire otherwise unemployed Russians; 120,000 Russian citizens were hired, supervised by some three hundred ARA employees. The American effort also led to a sustained attempt by the Bolsheviks to assure their own political control. The Cheka saw to it that the ARA would be purged of “undesirable” Russians who they suspected of harboring anti-Soviet tendencies. They constantly watched over the employees, fearing they would use their contact with Americans for counterrevolutionary purposes. Moreover, they sought to undermine the authority of American supervisors by finding and exploiting their weaknesses.

An example was David Kinne, a twenty-nine-year-old district supervisor of Saratov, who had a severe alcohol problem. The Cheka immediately took advantage of his apparent weakness by plying him with drink and providing women for his comfort. His absences from work became a major problem for the relief effort. The Bolsheviks used his drunkenness as the excuse to take control; to withhold food from their adversaries and give it only to their supporters among the populace. Eventually, Kinne was sent home in disgrace. Other ARA workers, like Harold Blandy, met a worse fate. He died from typhus spread by the ubiquitous lice. The Soviets gave him a public funeral in Moscow to honor the sacrifice he made for the Russian people; the Americans saw him as someone who became too close to starving children, and whose exposure to typhus was his own fault.

When American relief supplies were held up in ports due to the dysfunction of the Soviet railroads, the American Left accused Hoover of manufacturing the crisis to withhold relief in order to harm the Soviet government. Even Walter Lippmann, the most famous columnist in America, joined in public criticism. In fact, Hoover went out of his way to steer clear of such obvious propagandistic efforts, even though a lot of the corn was being siphoned off by Russian railroad workers. The trains, which were under the administration of the Cheka, were logjammed for three weeks while tens of thousands died of starvation. The Cheka allowed loyal railroad workers to take the corn for themselves, instead of shipping the trains out to ARA centers.

In addition, thousands of trains lay broken and in such poor condition that they could not be used for transporting corn and wheat. While 80 percent of the railroads were not in working condition, even those that could run took twenty-one days to travel 1,300 miles. Moreover, some 60,000 tons of supplies lay in waiting for trains that never arrived. The result was that in some provinces 25,000 Russians died of starvation each week.

By March of 1922, William N. Haskell, head of the ARA in Russia, was so frustrated by the Bolsheviks’ inability and unwillingness to get the railroads moving that he wrote an uncoded letter directly to Hoover, which he knew the Soviet authorities would read. In it, he documented attempted interference of the relief program by the Bolsheviks and protested their lack of cooperation with the ARA, terming it “obstructionist.” He recommended that food supplies be held up at port until the Soviet authorities began to cooperate.

This produced immediate results; the trains began to move. Haskell went to the Cheka’s top representative to the ARA, who immediately issued the order to send out the supplies by the previously stalled trains. Had Hoover made Haskell’s protest public, it would have created political havoc at home, and led to the collapse of the program, while also vindicating Hoover’s skepticism about the Bolshevik regime. But Hoover did not release the Haskell telegram, because he did not want to stir up anti-Soviet propaganda back in the United States.

By emphasizing such nuanced behavior, the film does a lot to restore Hoover’s image, usually seen through the lens of his discredited presidency, a focus that ignores the many years of his previous government service, all of which made him an extremely popular and highly regarded national political leader.

Logistics of how to get the food to the people continued to be an obstacle even after the trains began to function. One of the most dramatic scenes in the movie is of a caravan of 2,500 wagons of food being pulled by camels, the only pack animals hardy enough to endure the harsh Russian winter.

The famine of 1921 was the worst in Russian history, until the regime’s manmade Ukrainian famine of 1932–33. The 1921 famine was a result of bad weather and poor methods of working the land combined with the effects of the Great War, in which eleven million men and two million horses were taken from the countryside and from agricultural production. When the civil war between the Reds and the White Russians broke out in 1918, it was fought on the most fertile agricultural areas. Put together with the harsh policies of the Bolshevik’s war communism, which produced a peasant strike in protest against confiscation, the result was a reduction of land cultivation to a bare minimum. This presented a crisis of unprecedented proportions.

What Hoover actually desired, Patenaude explains thoroughly in his book, was to use food as a means to undermine Bolshevik power, by saving the victims of communism. He believed alleviating hunger would allow the Russian people to gain the strength needed to overthrow the Bolsheviks on their own. Hoover understood that starving people do not rebel, and that for an internal opposition to even develop, the first step was putting an end to constant hunger.

The irony, as the documentary notes, is that the ARA relief did not produce such a result. Instead, it had the momentary effect of strengthening a regime that was teetering at the edge of collapse, allowing the Bolshevik leaders to cement their control. As scholars in the film point out, Hoover’s relief effort did alleviate starvation, but the aid also worked to save the regime, rather than destroy it.

There were other consequences. Many of the Russians that worked with the ARA supervisors were educated women who could speak English. When the effort ended in 1922, twenty-six U.S. supervisors came home with Russian brides. Hoover and the ARA’s efforts in Russia were the vanguard of America’s policy to act as the chief organizer of aid in world crises. In this way, The Great Famine reacquaints a new generation with a largely forgotten story of how our ancestors generously came to the aid of a starving people. Our country’s work in that era is similar to the efforts we know of today in countries like Indonesia and Haiti.

Nevertheless, over the years, the Soviets would use this episode as part and parcel of a stream of regular anti-American propaganda. Along with the U.S. intervention in Siberia by the Wilson administration in 1918 (the so-called Siberian expedition), the USSR ideologists would argue that during their first great famine, Herbert Hoover used American aid to try to topple the Bolshevik government. They skillfully ignored the fact that this very aid prevented a crisis of even greater magnitude. Instead, they claimed it was simply more proof that from the very start, the United States perceived the Soviet Union as an enemy and sought to destroy it. The implication was that it was America, and not their own country, that was the main impediment to peace between the two powers. As Elmer Burland, one of the ARA men commented after the final banquet before the American relief workers left Russia, “the innate and complete antagonism between Russian Communism . . . and American individualism . . . remains an unsolved and unsettled conflict, and was in no way affected by the relief experience.”

When Nikita Khrushchev came to America on his famous trip in 1959, he told a press conference that “we remember [the ARA Relief] well, and we thank you.” But he then raised a “but.” He went on to say that “our people remember not only the fact that America helped us through ARA. . . . They also remember that in the hard time after the October Revolution, U.S. troops, led by their generals, landed on Soviet soil to help the White Guards fight our Soviet system.” Had this not taken place, Khrushchev argued, there would have been “no ruin and no famine. And you wouldn’t have had to help Soviet people through ARA.” In other words, the U.S. provided help for a famine it created. Perhaps it was too great a hope to think that the Soviets would praise the ARA without ideological spin. Yet, the real truth is that the ARA relief to Russia is a legacy we can be proud of.