It’s easy enough to wander through the Asian art wing of a large museum and skim over the fine print. Especially for those of us who have long since forgotten the details once memorized during early-morning undergraduate Chinese art history courses, the significance of specific locales may very well be lost in a blur of dynasties and dissertations, accented names and archaeological digs. We may look at the centuries-old head of a Buddha, or the thousand-year-old hand of a bodhisattva, and little fragments of stylistic recognition float to the surface: the wan smile, the crescent-shaped eyebrows, the elongated fingers and ear lobes, the lotus-posed legs. But we’re so fascinated by aesthetic details and ancient craftsmanship, we forget to pause to consider how the relic managed to make its way onto the white pedestal on which it’s now safe for viewing.

Time to dust off those Chinese art history books and get on the case. Next time you’re looking at a piece of Buddhist art created in China, play the placard-trivia game: More than likely, the piece was made between the fifth and ninth centuries CE, when Buddhism was the official religion of the land, and related temples and monasteries hadn’t yet fallen victim to the mass destruction of the religion and its objects by Emperor Wuzong, just before 900. Expert dating might have your hypothetical Buddha fall into the period marked by the Northern and Southern Dynasties (317–589). If it can be dated even more specifically, perhaps to the Northern Qi Dynasty (550–577), chances are you’re looking at a sculpture that once lived in the cluster of imperial cave-temples near the city of Fengfeng, in the southern Hebei province of northern China. These caves’ collective name is Xiangtangshan, which has been engrained in the minds of Chinese art scholars for decades because of its incredible significance to Buddhist art.

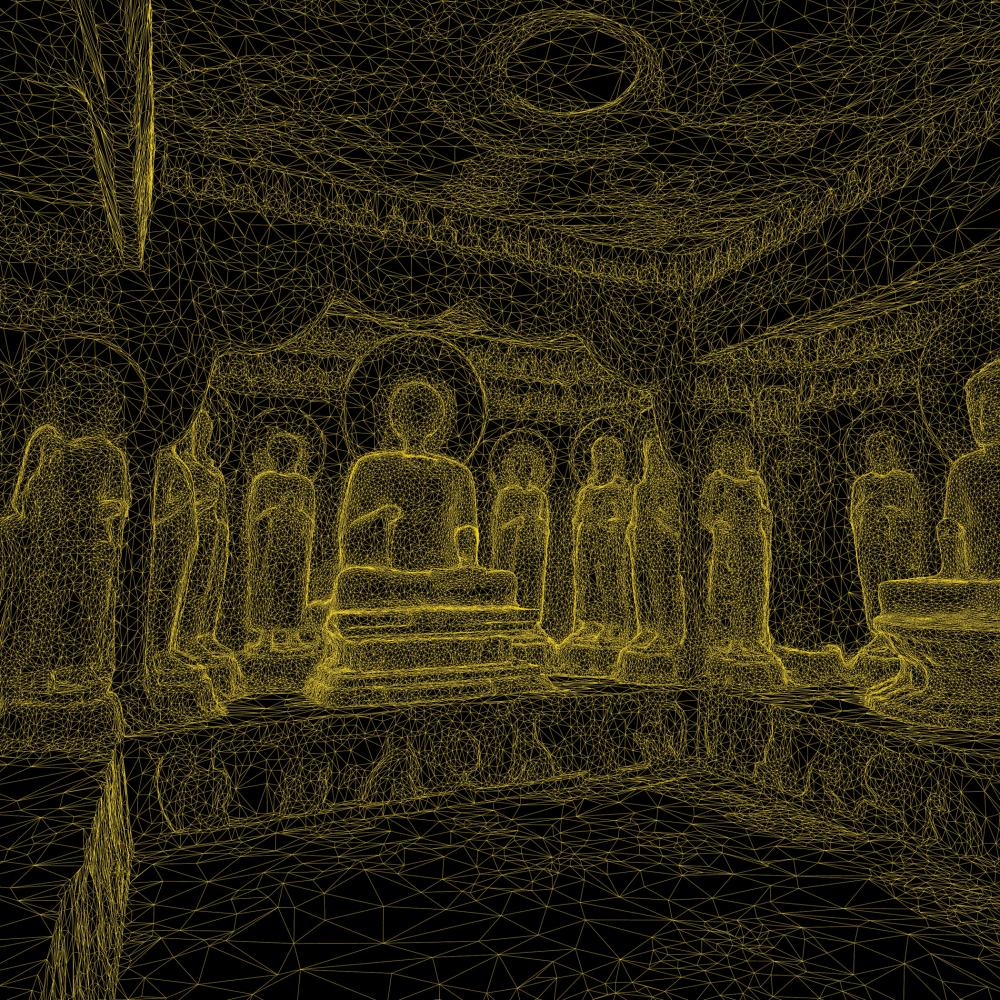

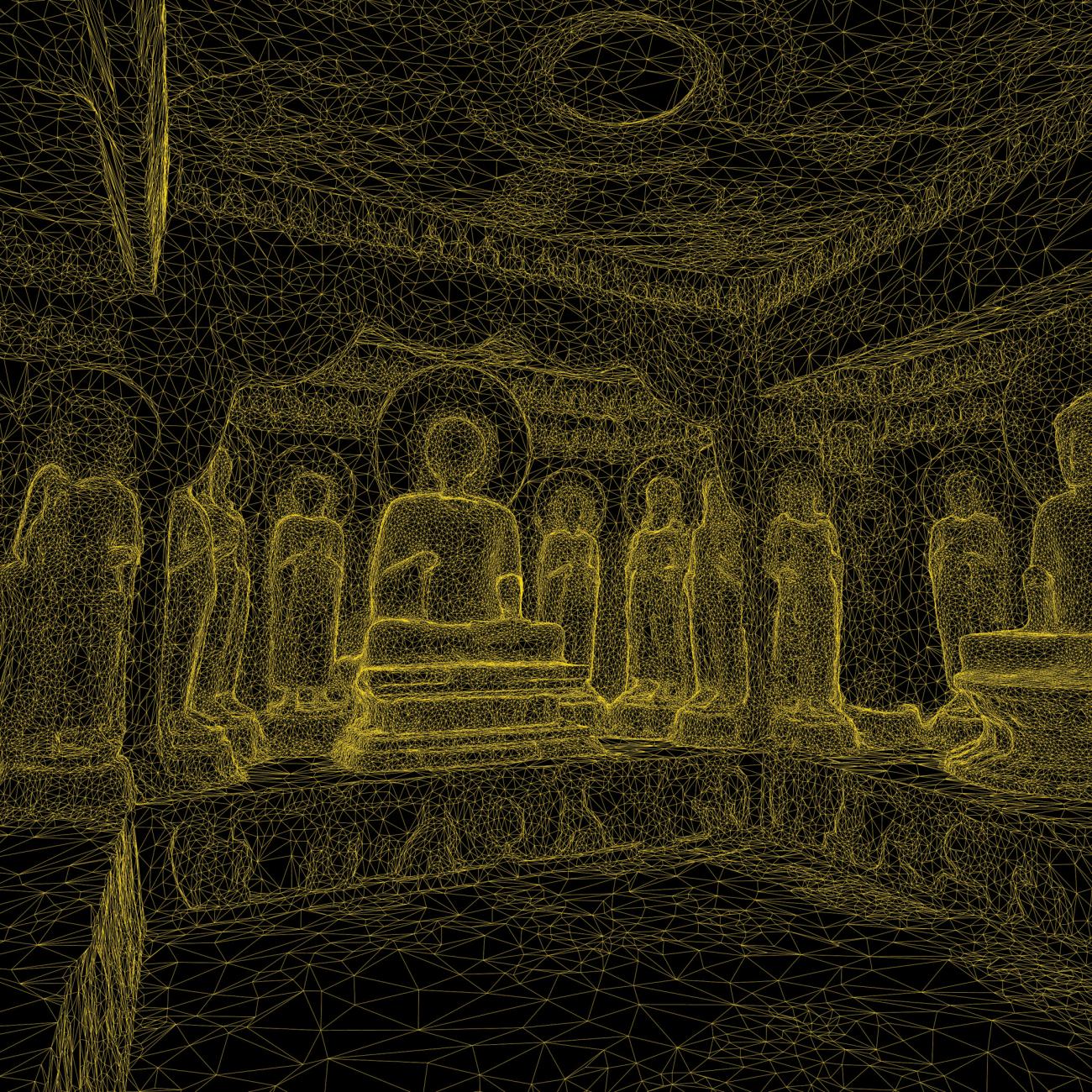

Translating to “mountain of echoing halls,” Xiangtangshan, along with a handful of similar cave-temple groupings within processional distance, represents the crowning cultural glory of the Northern Qi. Tucked into the Hebei province’s majestic mountainsides, the limestone caves of Xiangtangshan are accessible via stone steps from the villages below, their treads long worn by ancient pilgrims and modern tourists. Most of the caves are rectangular in shape and no larger than one hundred square feet or so: a modest and intimate size, only large enough for one or two visitors at a time. Commissioned by royalty, these so-called imperial caves are believed to have been used for family and state religious observances, in part because their walls are detailed with engraved scriptures popular during that era. There was a belief in the possibility of spiritual progress toward enlightenment for laypersons in the presence of Buddha, so Buddha sculptures abound.

Because many important relics of Buddhist art in China can be traced back to that era, it has long been an attractive research topic for Chinese art historians such as Katherine R. Tsiang, University of Chicago’s associate director for the Center for the Art of East Asia. For Tsiang, a native Chinese speaker, the fascination with the art of the Northern Qi dynasty was instilled during the writing of her dissertation on the Xiangtangshan cave-temples at the University of Chicago back in 1996. “I was attracted to it because it is so beautiful,” she says, “but also because not very much was known or written about where the sculptures came from.”

In the early twentieth century, when preservation was a distant afterthought to a wealthy collector’s desire to own a piece of ancient Chinese sculpture, Northern Qi relics began to go missing from Xiangtangshan’s caves and were scattered all over the world. The fall of the last dynasty, the Qing, combined with the uncertain, fledgling years of the Republic of China meant that there was no official oversight of the transitioning country’s religious and cultural sites. And as the collecting of Asian art became increasingly popular in the West, dealers and even local officials could pay to have important cultural artifacts removed and sold, traded, or shipped off at their whim. Often misdated or misidentified as originating from elsewhere in the region, Xiangtangshan’s sculptures became orphans, their true ancestry lost even to some of their collectors. Taking steps to track down their historical truth had never been a feasible reality.

It was a research project waiting to happen.

In conjunction with the opening of University of Chicago’s Center for the Art of East Asia, established in 2003 to facilitate and support teaching and research in this rapidly growing field, Tsiang set out with a small team of researchers and assistants to pick up where her dissertation left off. “It became a project of reconstructing the original appearance [of the Xiangtangshan caves] and also about learning about the historical and cultural context,” she says. In true twenty-first-century fashion, the “reconstruction” would be digital: She and a small team of researchers, plus a few technology and photography experts, would wander the globe in search of possible matches, taking 3–D laser-scans of alleged Northern Qi sculptures, then attempt to match them to a 3–D scan of the actual cavities of the Xiangtangshan cave-temples. Using 3–D visual-rendering software, the missing pieces could then be reunited with their ancient homes. If the pieces fit, it would complete a picture, virtually, that hasn’t been seen for nearly a century.

Tsiang already had a good idea of where to begin her search. An expert on the styles and facial types that were on the sculptures and on the caves, Tsiang sees everything visually. “You can’t just randomly go and scan something and expect it to fit into a cave,” she says. “So there was a foundation for going after certain pieces and scanning them. And then, of course, we made more discoveries along the way.”

For one, there was a collection of sculptures that had sat quietly for decades in the basement of Columbia University’s library. Knowledge of their whereabouts surfaced only recently when they were folded into the university’s Sackler Collections, then published and exhibited. Only after a close examination did it become apparent to Tsiang and her team that the sculptures likely originated from Xiangtangshan. For other orphaned sculptures existing independently in museums and collections around the world, the predicament was quite different: They had been attributed to the caves or the period, but positive identification had never been tested, let alone validated.

“Some of them, I still have my doubts about even though we’ve included them,” Tsiang says. She refers to the culminating exhibition, “Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan,” which documents Tsiang and her team’s work via a technologically savvy interactive presentation that opened in September at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art. “We tried to give the pieces that we’re most certain of consideration, and some of them we were able to match precisely the traces of the cutting [from the caves] with those on the backs of their heads and hands. That was very gratifying.”

Indeed: Imagine coming across a sculpture collecting dust in a dark corner of a museum display and discovering that it fits precisely into the cavity of a long-vacant Chinese temple thousands of miles away. In a way, it’s a wonder Tsiang and her team were able to match as many sculptures to the Xiangtangshan cave-temples as they ultimately did: about one hundred in all.

“A lot has to do with scale and traces that you can’t see in the caves,” Tsiang says of the matchmaking process. “I wasn’t sure, because I’d never seen any actual pieces from inside this cave, that they could have come from there, but it was very exciting to be able to locate them, finally. There was one head that I knew of just from the entryway, and there are traces where you can see where it was. I was looking for that head for years, and suddenly it appeared in the gallery of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: It had been in storage and had been brought out. There are all these stories about things that have resurfaced.”

Tracking down decapitated heads, hands, and any number of ancient torsos, crowns, limbs and objects became Tsiang and her team’s mission. Beginning in 2004, piled into a rental car with their hefty 3–D scanner, they scoured the country—and, as funding increased, the continent, and the world—in search of Xiangtangshan’s missing pieces. They drove from Chicago to Detroit and Cleveland; they shipped the scanner to the West Coast and Europe and followed it on airplanes. They scanned in London, Stockholm, Zurich, and Florence in one whirlwind trip, and made the trek all the way to Japan on another. They couldn’t go everywhere, of course—there are more pieces, still, as far as Australia—so the largest pockets of sculptures dictated their itinerary. On one of several trips to China, Tsiang and her team shipped their equipment ahead, but it never got past customs.

“We learned that there would be a steep duty charge to get it through customs,” Tsiang says, “and we had been given permission to photograph, but at that time we had not yet received the official permission to scan at the cave site.” The scanner was shipped back to Chicago and Tsiang and her team awaited approval—which, when it came through, stipulated that they would have to work with a Chinese group to do the scanning. In the end, Peking University was brought into the fold, and saved the day: Tsiang and her team arranged, via that institution’s Center for Information Science at the School of Electronic Engineering and Computer Science, to carry out the scanning with their own equipment. The timeline? A full year later.

Even scans that went off without a hitch were tedious and time-consuming. Once they’d landed in a particular destination, the team would set up camp for at least a night or two to complete the necessary grunt work: approximately a day, or half a day, to scan each piece. Some collections, like the Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery, with whom the University of Chicago ultimately partnered to present the exhibition, boasted more than a dozen pieces, which meant scanning for weeks on end in one location.

“What really took the time and effort, in addition to the research, was compiling this amazing database of information on the objects themselves,” Tsiang says. Citing the software used for the project, borrowed from Stanford University, Tsiang says, “The new technology is remarkable. One of the things of note is being able to put the models of the sculptures on the Web and being able to manipulate them.” Those efforts are a fascinating component of the finished “Echoes of the Past” exhibition: Alongside the actual sculptures, several dozen of which were successfully borrowed for the touring show, touch-screens invite visitors to swivel and rotate digital renderings of the works while learning to recognize their characteristic commonalities with the caves themselves.

The work for “Echoes of the Past” is completed, for now. But fragments plucked from the cave-temples of Xiangtangshan will likely continue to surface, even more so now that word of Tsiang’s team is spreading. Even shortly after the exhibition’s opening, Tsiang learned about a new piece on the market in Japan and was awaiting details.

“They are still circulating,” Tsiang says of Xiangtangshan’s orphaned Buddhist sculptures. “They’re still out there. I’m no longer actively looking for them, I’m moving on, but it’s good that other people have taken an interest.”