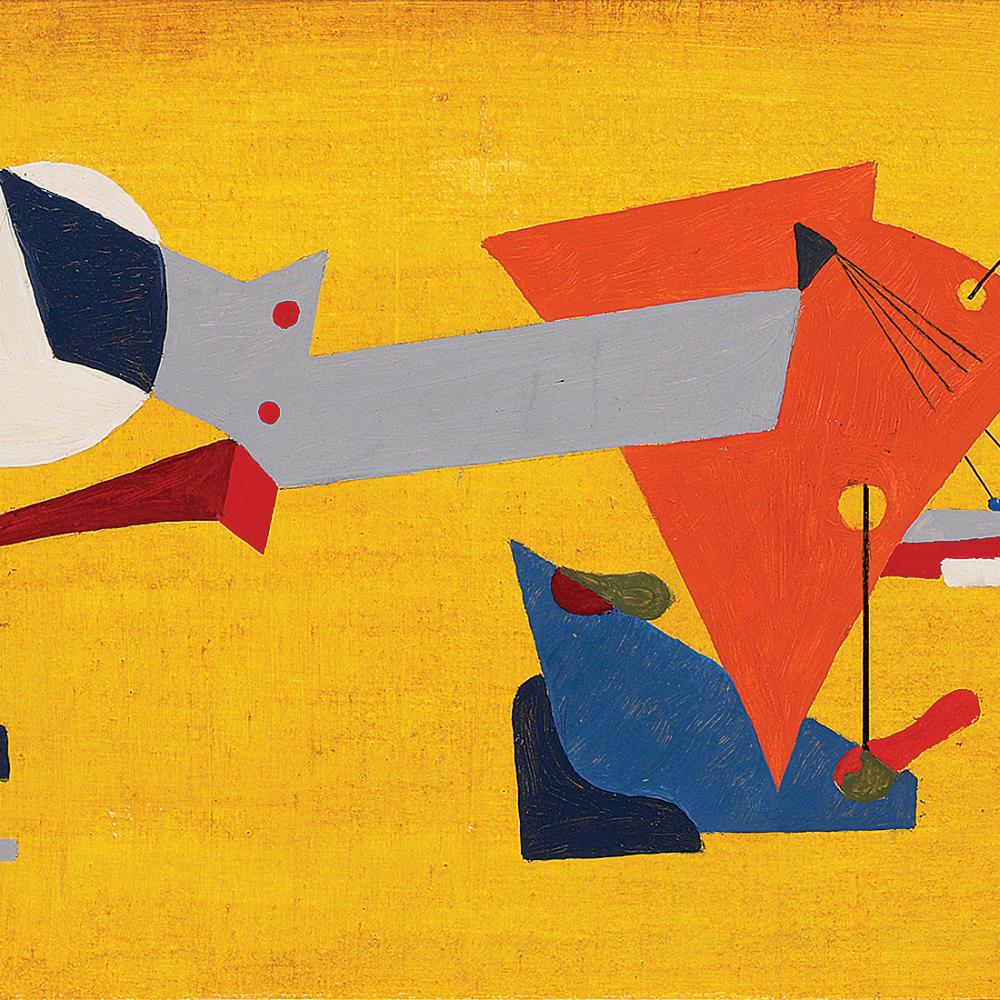

Abstract artist Esphyr Slobodkina’s works can be found on the walls of the most prestigious museums in the world and also on the bookshelves of nearly every children’s library in America. As one of the founders of the American Abstract movement in the 1930s, Slobodkina paved the way for critical acceptance of avant-garde art in the United States. And as a children’s book author and illustrator, she brought her fanciful collages to the imaginations of millions.

Born in 1908 in Chelyabinsk, Siberia, Slobodkina had a privileged childhood as the youngest daughter of the yard manager of an oil business, until the start of the Russian Revolution. With plans to emigrate to Palestine, her family escaped by train to the port city of Vladivostok only to find themselves stranded and broke, their bags full of worthless rubles. They landed next in Harbin, Manchuria, where Esphyr assisted in her mother’s successful couturier business and studied architecture.

After high school, Slobodkina came on a student visa to join her brother in New York City—although her brother mistakenly enrolled her in an academy for Christian missionaries instead of the National Academy of Design (NAD). Soon she was back studying art at NAD, an experience she called “stultifying.”

But it was at NAD that she met her mentor and future husband, the artist Ilya Bolotowsky. It was not a love match. As Slobodkina describes in her Notes to a Biographer, “The year being 1932 and the Great Depression at its worst, every right-thinking artist’s idea was to marry a good-looking, capable, young woman—preferably a teacher—thus acquiring in one fell swoop a model for his work and an economic anchor in what was usually a miserable bohemian existence.” For Slobodkina, the marriage meant American citizenship and farewell to NAD.

Although they were only married three years, Ilya and Esphyr remained friends for a long time and worked and exhibited together with the group they founded, American Abstract Artists. At one point, Slobodkina was the social secretary for the group, organizing their parties and welcoming European artists who were fleeing the Nazis. “In my Sixtieth Street apartment we gave parties: for as many as one hundred people with a lavish buffet supper and an abstract movie by Man Ray for entertainment; a more intimate reception and an afternoon tea for Mondrian,” Slobodkina wrote in her Notes. “It was fun, it was exciting, and I suppose it did no harm to my career.”

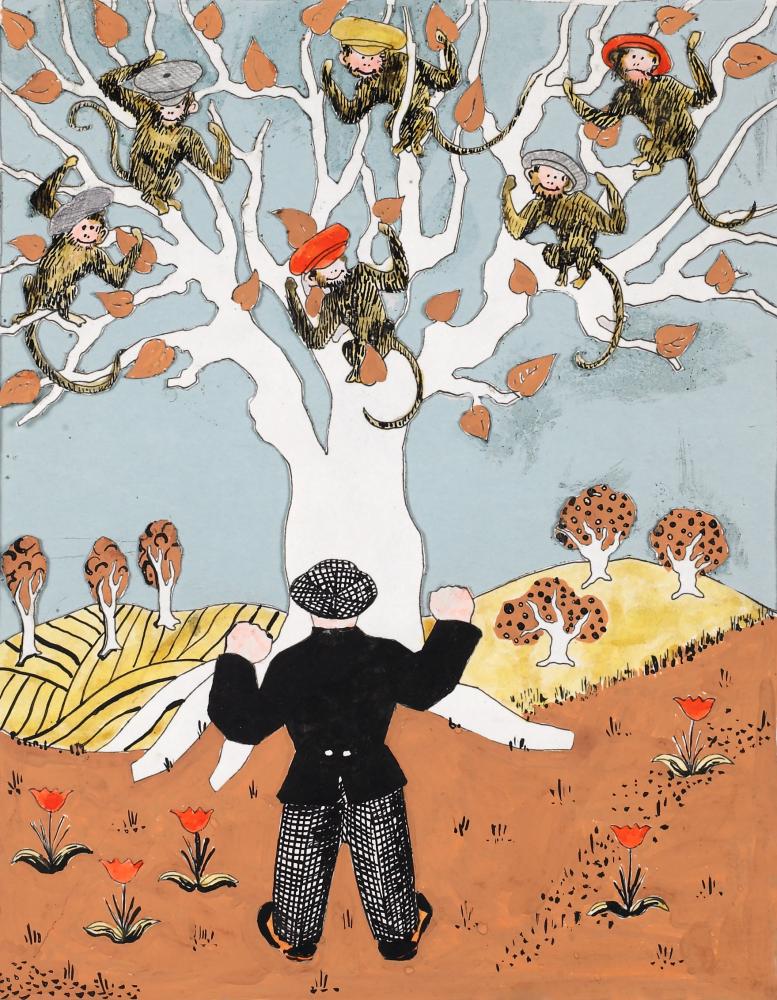

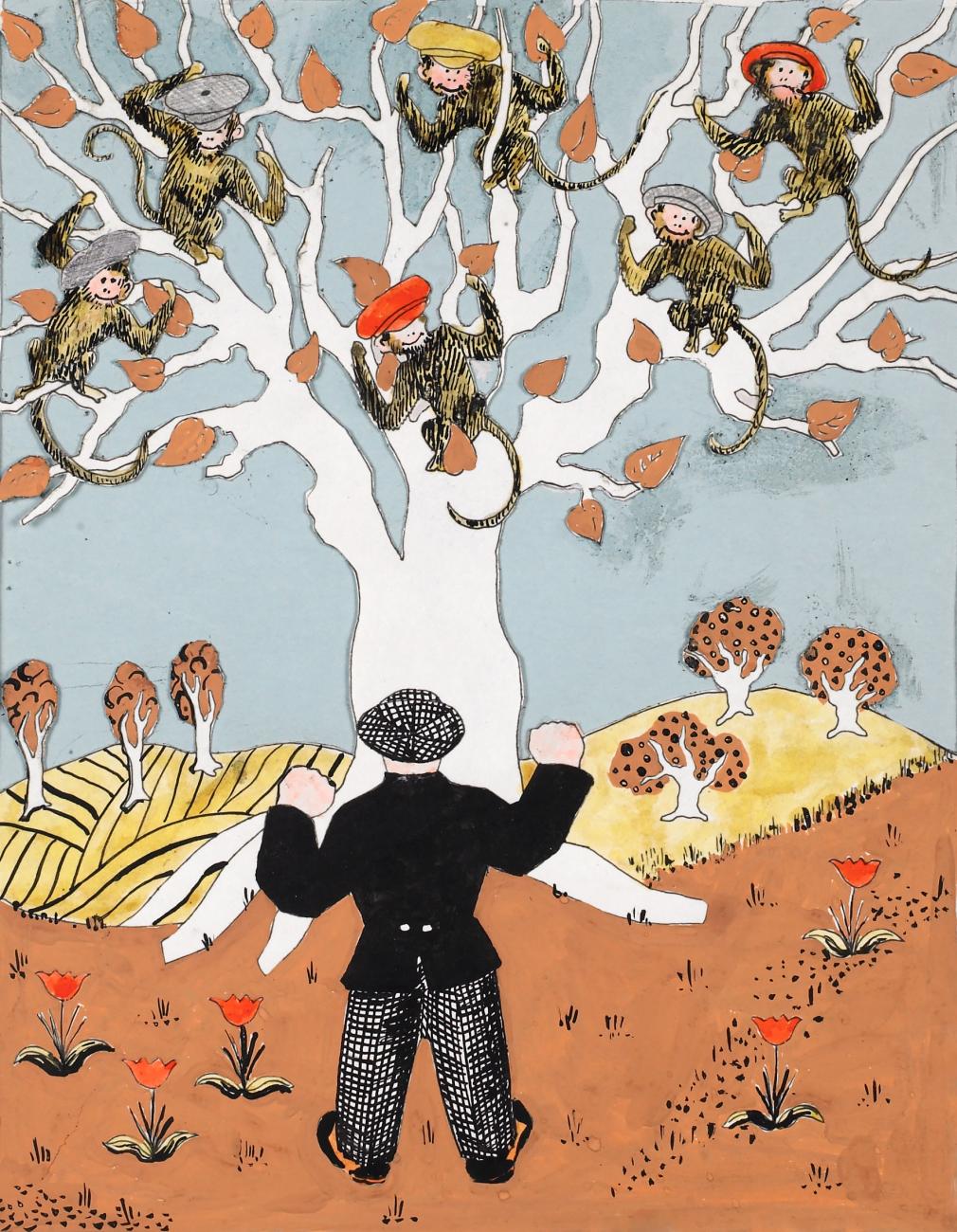

And her career as an artist was taking off. The American Abstract Artists held its inaugural exhibition in 1937 at the Squibb Galleries, and Slobodkina had her own one-person show at the New School for Social Research in 1938. That same year she had her first children’s book published, The Little Fireman, written by Margaret Wise Brown. It was the first American picture book done in cut-paper collage. Illustrating provided a steady income for Slobodkina and she ended up either illustrating or writing (or both) twenty-four books—four with Brown. Her most famous was the 1940 Caps for Sale, based on a Russian folktale that she remembered from her childhood. It has been in print for over sixty years and translated into French, Hebrew, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Xhosa, and Afrikaans.

Critic Leonard S. Marcus believes that Slobodkina’s books had a long reach. “Directly or indirectly, the example of her work set the stage for the distinctive contributions to the picture book of, among others, Leo Lionni, Ezra Jack Keats, Eric Carle, Ed Young, Lois Ehlert, and Ellen Stoll Walsh,” he writes.

Her children’s books have also served as an entrée into understanding her abstract painting and sculptures. In honor of what would have been her one hundredth birthday in 2008, the Slobodkina Foundation in Glen Head, New York, organized a traveling exhibition of her works, ranging from a park scene she painted when she was sixteen, to original collages made for her books, to the last sculpture she created in 2001, at the age of ninety-three. “Rediscovering Slobodkina: A Pioneer of American Abstraction” makes its final stop at the Sheldon Museum of Art in Lincoln, Nebraska, from January 26 through April 18.

“We have broken attendance records at every venue so far,” says Ann Marie Mulhearn Sayer, executive director of the Slobodkina Foundation, who will be giving talks at the museum as part of the exhibition’s programming. “Because of familiarity with her children’s books, people who have never come to see an abstract show will come in.”