The Armory Show at 100

Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887-1968), Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 35 1/8 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950, 1950-134-59. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

Courtesy, New-York Historical Society

Marcel Duchamp (French, 1887-1968), Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 35 1/8 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950, 1950-134-59. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

Courtesy, New-York Historical Society

In 1913 New York was a city in rapid transition, the most urbane metropolis in a country that was becoming a leading power in the emerging, modern world. It was the age of the New Woman, when the bizarre silhouette of the bustle and corseted waist were abandoned for the greater comfort of more fluid dress. Model T cars outnumbered horse-drawn carriages and shared the streets with suffragettes marching for the vote. Homes were being outfitted with telephones and electric lights and audiences filled Vaudeville palaces and danced the Turkey Trot in ragtime clubs. Yet few were prepared for jolt that rocked New York City on February 17, when the International Exhibition of Modern Art opened at the 69th Regiment Armory, with over 1,350 paintings, sculpture, paints, and decorative arts by progressive American and European artists. It was a landmark event and is now regarded as the most significant art exhibition ever held in the United States.

To celebrate the centennial anniversary of the exhibition, the New-York Historical Society is hosting The Armory Show at 100, which opened October 11, 2013, and will run through February 23, 2014. It reassembles 100 astutely selected pieces from the original show by artists ranging from Marcel Duchamp, Henri Matisse, Picasso, and Kandinsky to Van Gogh, Whistler, John Sloan, and Goya. A substantial catalog accompanies the exhibition it accompanied and the website , funded by NEH, offers extensive information about the Armory Show and New York in 1913, as well as a rich collection of educational materials for teachers.

The 1913 show was organized by a group of American artists who wanted to exhibit progressive American works and introduce the broad public to modern European avant-garde art. Some American artists were exploring modernism through European movements, others, like John Sloan, George Bellows, Robert Henri, and Mahonri Young, sought an American modernism in the grittier side of the Gilded Age and images of the working class and the poor, and urban scenes of industry, decay, and new growth. Later, these artists were described with derision as the Ashcan School.

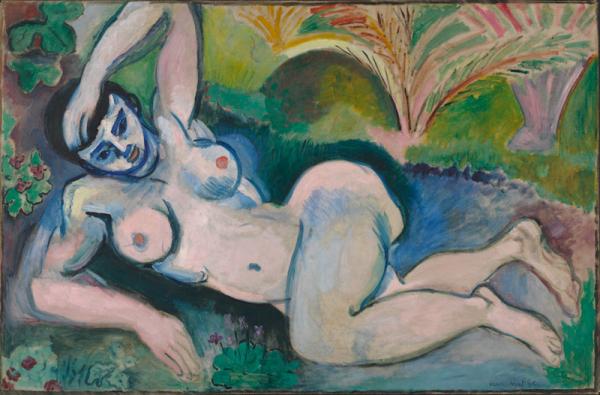

The galleries of the Armory exhibition were arranged in a sequence that intended to present the evolution of modern art from the nineteenth century toward the avant-garde art of Europe. The general public, who valued art of refinement, beauty, and noble thought, was flabbergasted and responded. Three works were particularly reviled: the shattered forms of a figure in motion in Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (an explosion in a shingle factory, the rude descending a staircase—rush hour at the subway); the extremely simplified form of Mlle Pogany I by Brancusi (a portrait bust of a white Leghorn’s egg, an underdeveloped and deformed infant); and the exaggerated colors and shapes of Blue Nude by Matisse (vulgar, distorted and toadlike). In 1913, the Gibson Girl type still had currency as the popular ideal of the New Woman in America: young, active, and independent, she had slender, athletic build and dressed in the latest fashions. A captivating beauty, the Gibson girl was alluring, even teasing, but always maintained the chaste, upper hand. The revolutionary European art that audiences experienced at the Armory show must have been especially rankling, not only in the face of popular notions of modern female beauty, but also as modern contributions to the venerated tradition of the female figure in art. Given this context, it is little surprising that one man after seeing the 1913 exhibition, concluded “Something is wrong with the world.”