Native Students Help in Seminole Language Documentation

Delaney Pennock (student), De Lois Roulston (speaker), Lucy Tiger (speaker), Alex Hicks (student), Sarah Martin (student). They are standing in front of the Seminole Nation's Pumvhakv School.

Image by Jack Martin.

Delaney Pennock (student), De Lois Roulston (speaker), Lucy Tiger (speaker), Alex Hicks (student), Sarah Martin (student). They are standing in front of the Seminole Nation's Pumvhakv School.

Image by Jack Martin.

Roughly half of the world's 7,000 languages are endangered and risk extinction. When a language dies, we lose not only the language, but the unique cultural, historical, and ecological knowledge bound up in it. These languages are an irreplaceable treasure, not only for the communities who speak them, but also for scientists and scholars.

Since 2004, the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities have teamed up to address the rapid loss of languages worldwide through the grant program, Documenting Endangered Languages (DEL). The program--which has awarded some $40 million in funding to document hundreds of at-risk languages worldwide--supports linguistic fieldwork and other activities relevant to documenting and archiving endangered languages, including audio and video recording, linguistic analysis, and the preparation of dictionaries, grammars, and text samples.

Documenting Endangered Languages seeks to build a research infrastructure which means ensuring long-term digital preservation of language materials and providing support for professional development for academic linguists, as well as for heritage speakers and members of the community.

One repository that has benefited from DEL is the California Language Archive, based at University of California, Berkeley, which provides access to researchers’ field notes, audio and video recordings, photographs, and other language resources that document the many native languages of California. Another repository supported through DEL is the Archive of Indigenous Languages of Latin America, based at the University of Texas at Austin, where field notes, ethnographies, audio and video recordings, photographs, and other language documentation materials are accessible to researchers, students, community members, and the public.

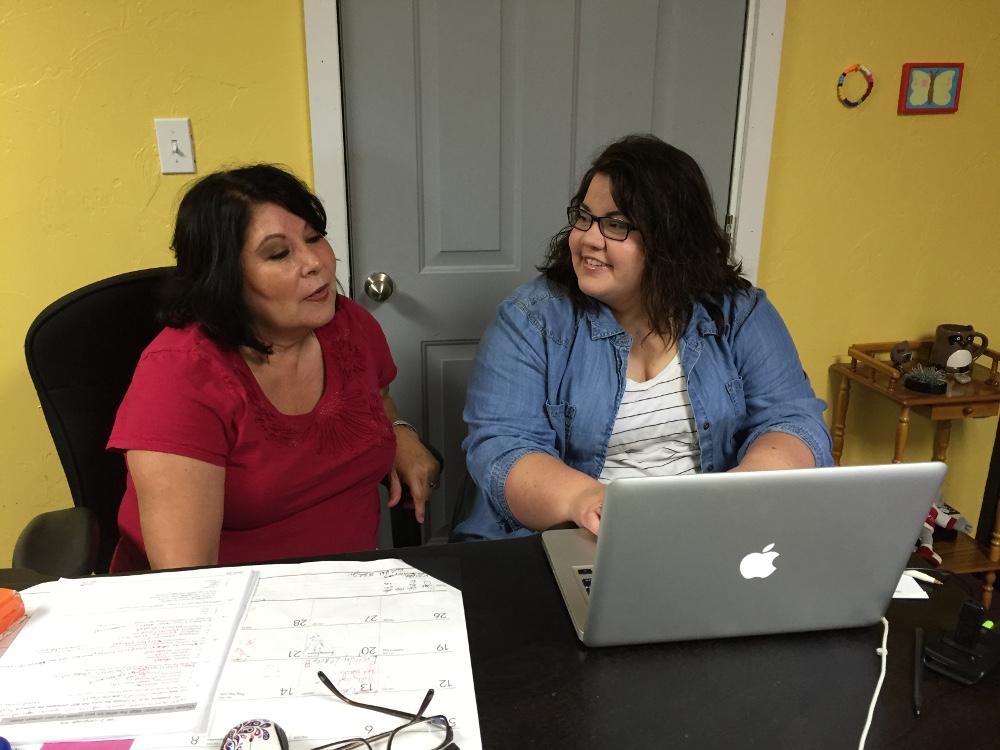

Another goal of the DEL program is to encourage community collaborations. Linguists typically work together with indigenous groups, often training students and speakers in linguistic field methods, such as video recording or language transcription, that can sustain language preservation efforts. Such community collaborations are key to the success of the projects.

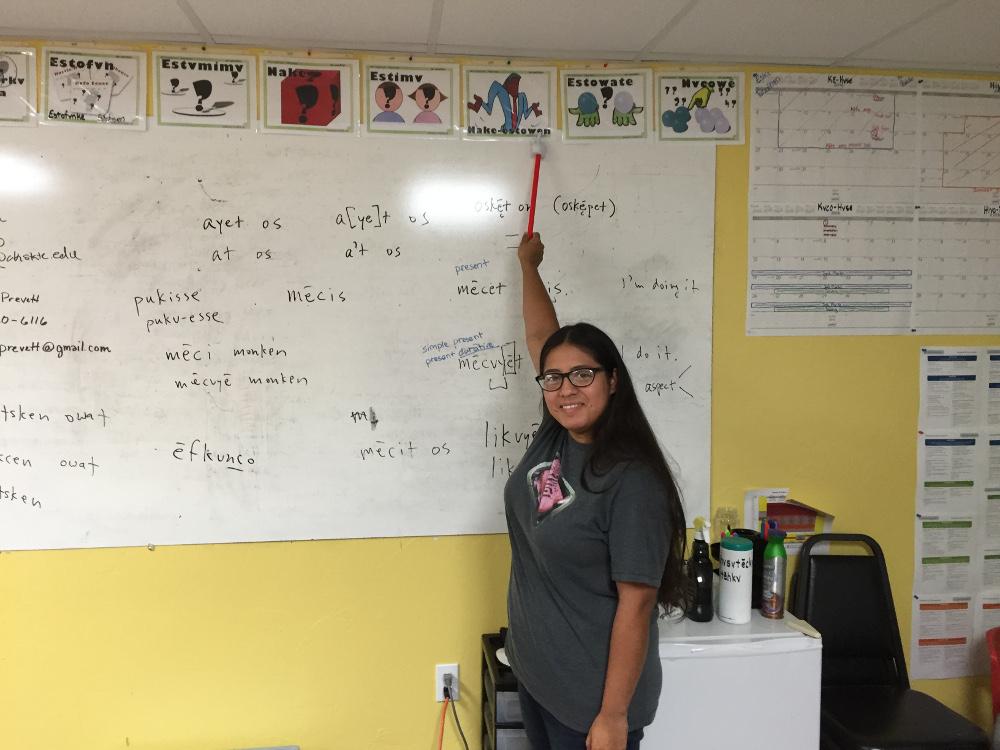

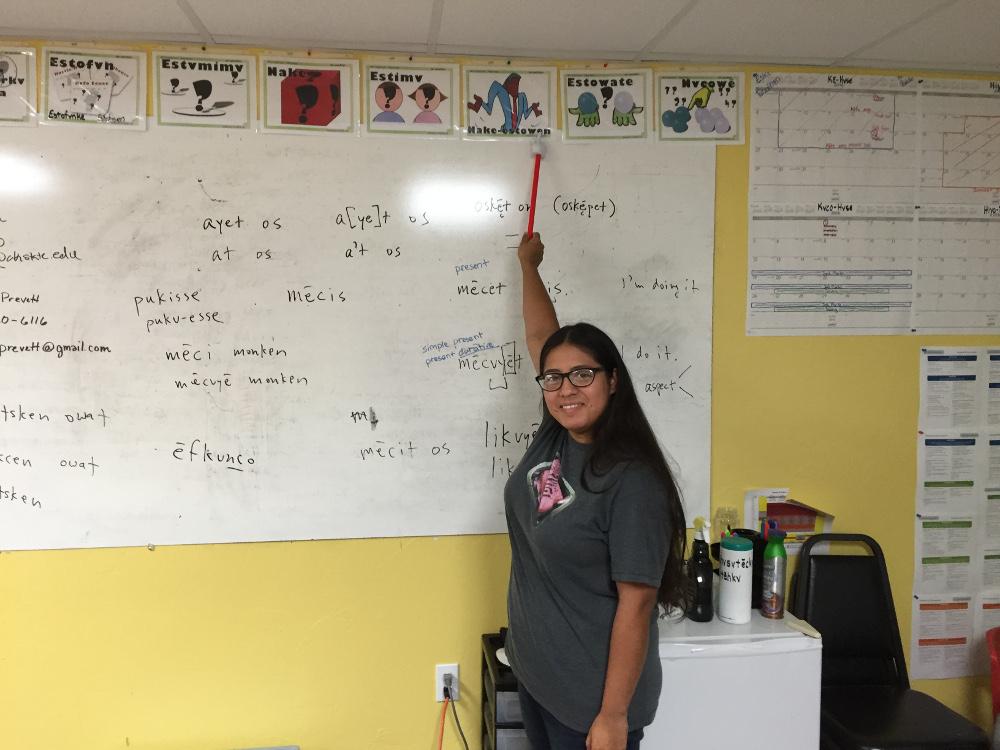

There are approximately 150 Native American languages still spoken in the United States. A language like Navajo, with over 100,000 speakers, is considered vital. But most Native American languages are at risk of extinction, with few first speakers remaining. In Oklahoma, Jack Martin, Professor of Anthropology at William and Mary College, is working with Native American students to undertake audio and video recordings of elderly speakers of Muskogee (also known as Creek).

Muskogee was one of the major indigenous languages of the American South, and is now spoken by the Seminole Tribe in Florida and the Muskogee (Creek) Nation and the Seminole Nation, both in Oklahoma. Scholarly resources have been compiled for the language--dictionaries, grammars, and publication of texts, but there have not been any analyzed recordings of speakers in natural discourse. For languages like Muskogee, facing extinction, it is essential to record informal conversation and contemporary speech, since once documented, they can be taught to younger language learners and other members of the community.

In the William and Mary project, native students from Bacone College, in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and from the Seminole Nation’s Pumvhakv School, in Seminole, Oklahoma, joined native speakers of Creek to record songs, oral histories, and conversations about traditional activities and worked with experienced linguists to analyze the recorded speech. And in the summer of 2016, these same students attended the CoLang Institute at the University of Alaska to learn more about the technology of language documentation. CoLang, also known as the Institute on Collaborative Language Research, is committed to sustaining language diversity by developing resources of value to the language community itself and, to that end, supporting ethical collaborations between academic and community linguists.

The Muskogee project will help ensure that a new generation of Muskogee speakers can be nurtured, and a connection is made between younger members of the Creek community and their language as a part of their cultural identity. The recordings of native speakers and linguistic analysis of their speech will be archived at the Sam Noble Museum of Natural History at the University of Oklahoma and will be made available on the Web. You can listen to some of the recordings on the project’s Website at: http://muskogee.blogs.wm.edu

Projects such as the ones highlighted here contribute to language documentation at the same time that they connect indigenous community members to their heritage and language, contributing to language vitality, as well as community health and well-being.