Chronicling America’s Historic German Newspapers and the Growth of the American Ethnic Press

From the old to the new world. German emigrants for New York embarking on a Hamburg steamer.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionWashington, D.C. 20540 USA.

From the old to the new world. German emigrants for New York embarking on a Hamburg steamer.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionWashington, D.C. 20540 USA.

This article is the first in a series about the history of the ethnic and foreign language content of “Chronicling America,” a database of historic American newspapers from 1836 to 1922 supported by NEH and the Library of Congress. Future articles will feature newspapers in French, Italian, and Spanish and those written for the Jewish community.

Extra! Extra! German Immigrants in the United States

Were Germans the most influential group in the ethnic press? For a time, yes! In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Germans came to the United States in droves. For decades, Germans were the largest non-English-speaking immigrant group in America. Between 1820 and 1924, over 5.5 million German immigrants arrived in the United States, many of them middle class, urban, and working in the skilled trades, and others establishing farming communities in the West. Their numbers and dedication to maintaining their language and culture made Germans the most influential force in the American foreign-language press—in the 1880s, the 800 German-language newspapers accounted for about 4/5 of non-English publications, and by 1890, more than 1,000 German newspapers were being published in the United States.

Germans were the first non-English-speaking group to publish newspapers in America. At least until the First World War, these newspapers were critical for maintaining German American identity. For many German immigrants, the emphasis was on the first part of that identity—they were Germans first, and sought to become Americans without relinquishing their German-ness. The group established a pattern that other immigrant groups followed later. They came to America, settled into cultural enclaves, and constructed microcosms of their society in the new country. Maintaining their language and printing newspapers in their native language was critical to that process. Some of the many German-language newspapers published in the United States may now be found in Chronicling America.

What is Chronicling America?

Chronicling America is a freely accessible web site providing information about and access to historic United States newspapers published between 1836 and 1922. To date, more than 7.8 million pages representing 32 states and the District of Columbia are available on the site. Chronicling America is produced through the National Digital Newspaper Program, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Library of Congress, and state projects. NEH awards enable states to select and digitize newspapers that represent their historical, cultural, and geographic diversity, and to contribute essays containing background information about each newspaper and its historical context. The Library of Congress unifies all content provided by states and permanently maintains the digital information. Chronicling America is freely available on the internet. Users may search the millions of digitized pages contributed by state projects and the Library of Congress and consult a national newspaper directory to identify newspaper titles available in all types of formats. This effort ensures that users will continue to have access to this historical record even as technology changes.

The Fraktur Challenge

Chronicling America currently offers full-text digital access to 24 German-language newspaper titles—over 150,000 pages—with more being added all the time. Making these papers available and searchable digitally was no small feat for the Library of Congress, however, because the papers are printed in Fraktur script. The many angles, breaks, frills, and different weights used in Fraktur, compared to more common square typefaces, makes the writing in these papers particularly difficult to analyze with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software, the primary tool for creating searchable text. While Fraktur typesetting was quite common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is seldom used today. Until recently, software tools that could easily read modern German were not equipped to read texts printed in Fraktur.

In 2008, the European Union embarked on a three-year program called IMPACT, which brought national libraries together with software development companies to improve access to historic texts. By the final IMPACT conference in 2011, the program had produced several outcomes in text recognition that led to revision of the Library of Congress’s technical guidelines to incorporate non-English language publications. These outcomes included improved recognition tools for Fraktur text as well as other European languages. Taking advantage of these, Chronicling America has added indexing and stemming systems—tools that understand the dictionary and grammar of a particular language and enable searching in it—for German, French, Spanish, Italian, Danish, Hungarian, Norwegian, Portuguese, and Swedish. The Library continues to work with state partners and software vendors to refine searchability and add new languages to Chronicling America.

The German Press

While the software that enables digital access to it is new, publishing newspapers in the Fraktur script is anything but: the first German newspaper printed on American shores predated the Revolution by almost half a century! In fact, the first foreign-language newspaper in the United States was in German—Die Philadelphische Zeitung, begun by Benjamin Franklin in 1732 in his Philadelphia printing shop. While this paper folded after only a few issues, German immigrants to Pennsylvania established numerous popular German publications in the eighteenth century. By 1802, German newspapers were published in Philadelphia, Lancaster, Reading, Easton, Harrisburg, York, and Norristown—and that was just in Pennsylvania! The massive wave of immigration in the next century brought many Germans to America and to the fore of newspaper publishing. Joseph Pulitzer, for whom the Pulitzer Prize is named, got his start as a reporter for a German-language publication in St. Louis called the Westliche Post. While many German editors and publishers worked for English-language publications, others were intent on using newspapers to preserve their language and culture in the new country.

Political Tides

Like nineteenth-century newspapers in most any language, German publications expressed a wide range of strong opinions, reflecting the views of their editors—but often changing politics with changing times. For example, serving the huge population of German-speaking immigrants in Cincinnati was the Tägliches Cincinnatier Volksblatt. Established in 1836, the paper at first supported Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party and its immigrant-friendly ideology. The paper later adopted a more independent stance, however, to appeal to a wider reader base. The Indiana Tribüne in Indianapolis, on the other hand, morphed from a pro-Republican to a pro-Labor publication, reflecting the late nineteenth-century labor movement in America—its publishers boasted in 1886 that it was “the only German daily workingman’s paper published in Indiana.”

The series of failed revolutions in Europe brought many radicals to United States’ shores after 1848. The “Forty-Eighters,” as these radicals were known, were in fact so highly represented among German newspaper editors that for a long time Forty-Eighter sentiment was thought to reflect the German immigrant community as a whole. Socialist publications such as Der Tägliche Demokrat (Davenport, Iowa) represented the democratic movement spreading across Europe in the 1840s. The paper’s motto was “To each his own,” and its editors opposed slavery and supported popular freedom and social reform. Just as often, however, the changing views advocated by German-language newspapers indicated the growing mainstream political influence of German Americans. The Minnesota Staats-Zeitung in St. Paul, for example, was begun by a Forty-Eighter who had been exiled from Germany for his support of the revolutions. The paper presented extensive coverage of the 1860 elections, including the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and particularly the Republican courting of German-American votes through endorsement of the Homestead Act of 1860 and opposition to limiting the rights of naturalized citizens to vote.

Local and Global

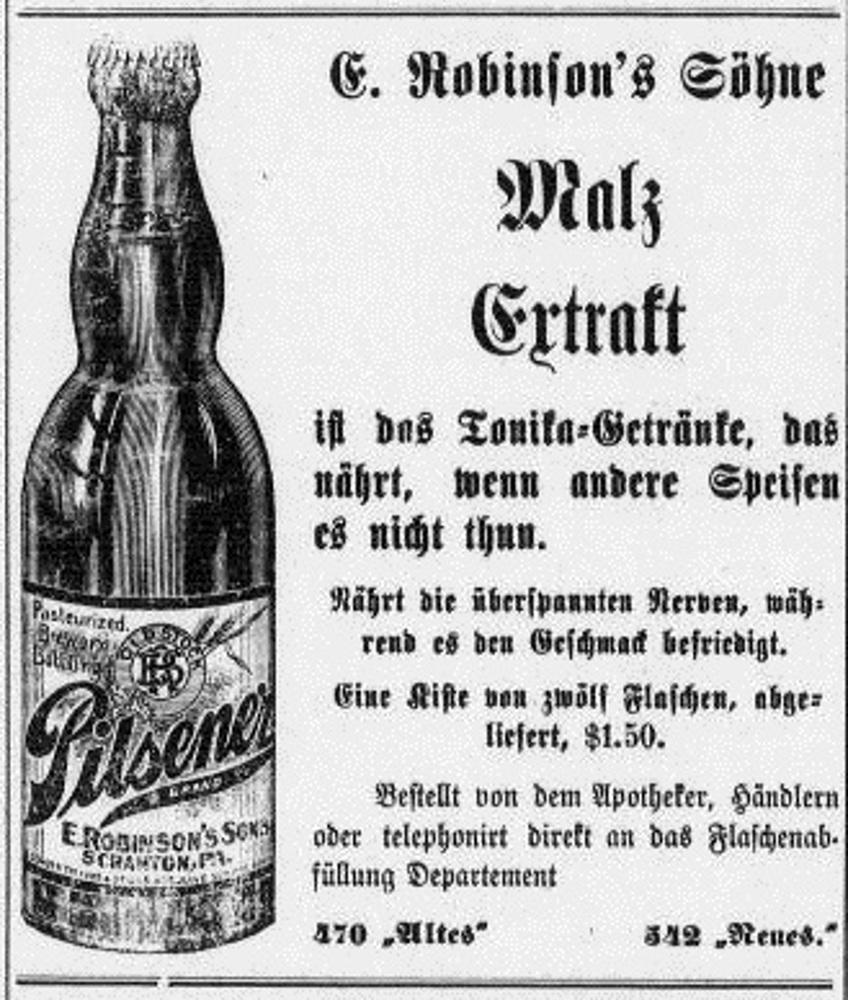

Balancing local interest stories with global affairs was a primary issue for newspaper editors. German-language newspapers represented a wide range of interests, with some focusing almost entirely on international news, mostly from Germany, for immigrants who maintained strong family ties to their homeland. Other newspapers published mainly local and lifestyle news of interest to immigrant communities. Der Nordstern (St. Cloud, Minnesota) focused on local news of relevance, as did the Scranton Wochenblatt (Scranton, Pennsylvania), which published serial novels, recipes, human interest stories, and in-depth articles on culture and religion. Baltimore’s Der deutsche Correspondent, founded in 1841, was one of the first German newspapers to prioritize both foreign and domestic news, where earlier papers had focused on news from Germany. Local items included detailed marriage and death notices that might not appear in English-language publications.

Anti-German Sentiment

While the German-American community and its press enjoyed a dazzling cultural prominence in the late nineteenth century, both fell on hard times during the First World War. They were accused of being too sympathetic to Germany—and disloyal to the United States. In fact, anyone using the German language was regarded with suspicion. States banned the teaching of German in schools, which had been commonplace in earlier decades. Many German Americans, seeking to prove that they were neither spying for Germany nor endorsing the German war effort, stopped speaking German and bought war bonds to show their patriotism.

Suspicion of Germans was reflected in the near ruin of the German-language press by 1920. Newsstands boycotted German newspapers, refusing to sell them. In October 1917, the headquarters of the Tägliches Cincinnatier Volksblatt was raided by federal agents looking for evidence that the newspaper sympathized with Germany.

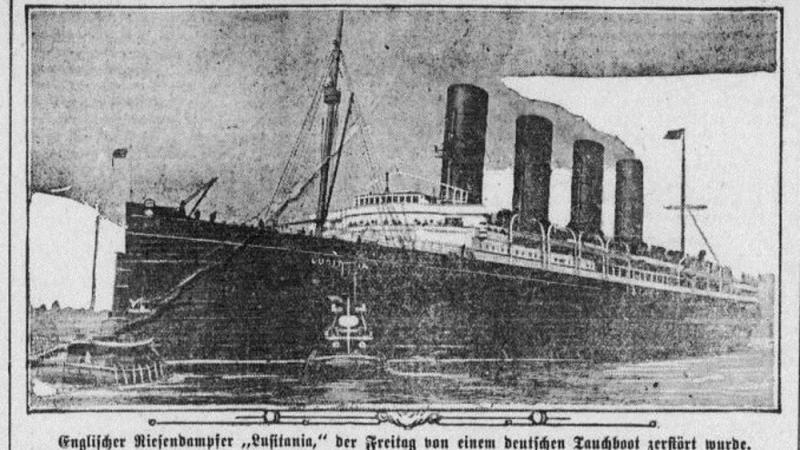

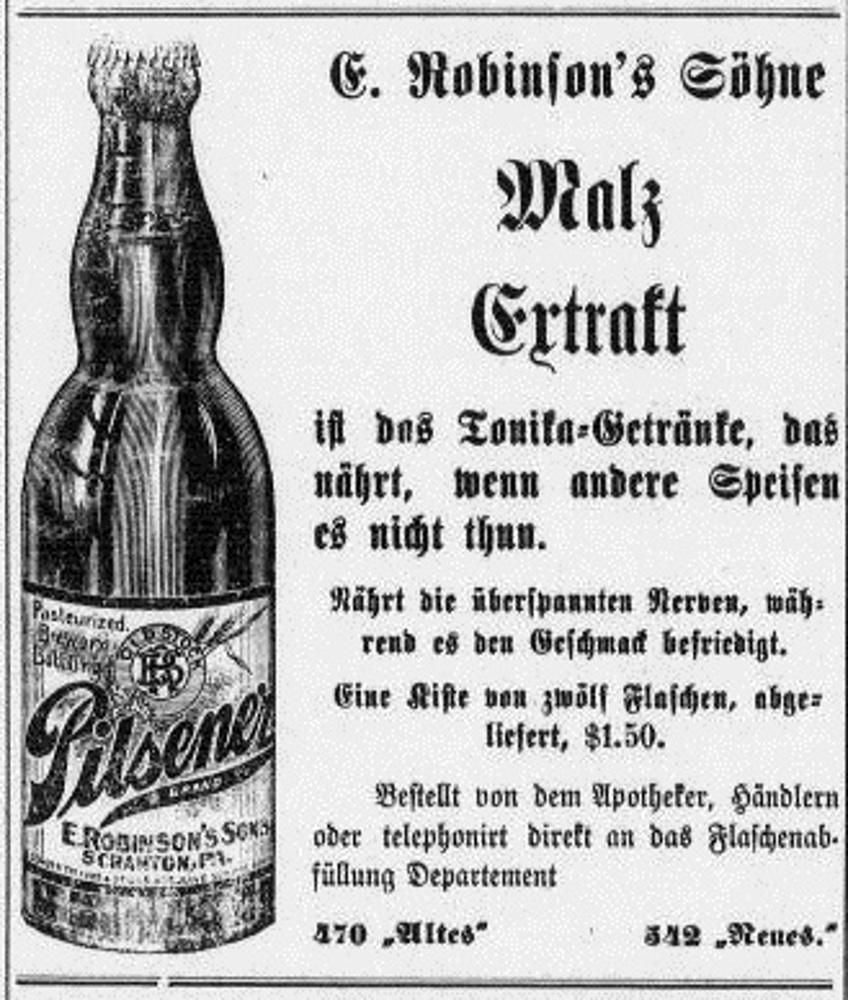

Staunching the Flow of Advertising and Alcohol

Often, the reason for German-language newspapers’ demise was a precipitous drop in advertising revenues. The Scranton Wochenblatt, for example, had expressed sympathy for the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire) after the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914 and noted that there were munitions on board the Lusitania when a German submarine sank it in 1915. When they closed their doors in 1918, the paper’s editors stated that advertising had dried up with “everything German” under suspicion. The Temperance Movement and Prohibition also had effects on the German community and its newspapers. The brewery industry was a large part of German culture transported to the United States. No longer able to advertise beer, German-language newspapers lost revenue—sometimes to the point of collapse.

By 1920, a number of the newspapers in Chronicling America had closed their doors and silenced their presses, including the Indiana Tribüne (Indianapolis, Indiana), Der Tägliche Demokrat (Davenport, Iowa), Tägliches Cincinnatier Volksblatt (Cincinnati, Ohio), and the Scranton Wochenblatt (Scranton, Pennsylvania). Baltimore’s Der deutsche Correspondent, which once enjoyed a circulation of 15,000, closed in April 1918. Once by far the foremost element of the foreign-language press in America, German-language newspapers never again attained such prominence. Studying the newspapers at their heyday and their decline, however, reveals much about German American culture in the United States.