Inspiring Hope in Place of Despair

from L to R: Commissioner Pelicia Hall, Mississippi Department of Corrections, Michael L. Chambers, II, Program Analyst, NEH, Stuart Rockoff, Executive Director, Mississippi Humanities Council, Deborah L. Mack, Associate Director Strategic Partnerships, NMAAHC, Ron King, Supt. CMCF, Jon Parrish Peede, Senior Deputy Chairman, NEH

Grace S. Fisher, Mississippi Department of Corrections

from L to R: Commissioner Pelicia Hall, Mississippi Department of Corrections, Michael L. Chambers, II, Program Analyst, NEH, Stuart Rockoff, Executive Director, Mississippi Humanities Council, Deborah L. Mack, Associate Director Strategic Partnerships, NMAAHC, Ron King, Supt. CMCF, Jon Parrish Peede, Senior Deputy Chairman, NEH

Grace S. Fisher, Mississippi Department of Corrections

Prisoner education efforts shine a light of hope into the lives of inmates and their loved ones. While paying their debts to society, the incarcerated population is no less deserving of access to the humanities and letters, as a key to self-betterment within an environment all too conducive to despair. According to Professor Elizabeth Hinton of Harvard University, about one-third of penal institutions in the United States today offer classroom instruction in a variety of subjects to inmate learners. The ripple effects of such targeted educational intervention lift up not only those imprisoned, but their families, communities, and society as a whole. The prisoner education programs sponsored by state humanities councils provide great dividends for the future.

In the Magnolia State, promising educational efforts backed by the Mississippi Humanities Council (MHC) are changing the lives of prisoners the state over. The Prison-to-College Pipeline, which includes the University of Mississippi, Jackson State University, and the MHC as supporters, is a worthy Deep South cousin to the Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project in spreading the humanities to an underserved population. At penal institutions like the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl, Mississippi, prisoners moreover are encouraged to offer input into the structure of their own class curriculums. Under the Pipeline program motivated inmate learners are not only immersed in the great literature of authors like Langston Hughes and Ernest Hemingway, but can actually earn college creditto be applied at state institutions of higher education. Such a special arrangement builds a bridge of hope for participating inmates toward achievable rewards in the future. Professors Stephanie Rolph of Millsaps College and Otis Pickett of Mississippi College have generously contributed their time to the program, finding the experience personally fulfilling.

While still incarcerated, the inmates of Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi have, under the Prison Writes program, the opportunity to pen their own stories and experience the pride of seeing their work in print. Launched in 2014 with the support of MHC, and under the guidance of professional writer Louis Bourgeois, Prison Writes enables students to compose their own narratives after weeks of editorial lessons and navigating the books of others. Having their efforts preserved in official publication provides an affirming capstone of achievement for such students.

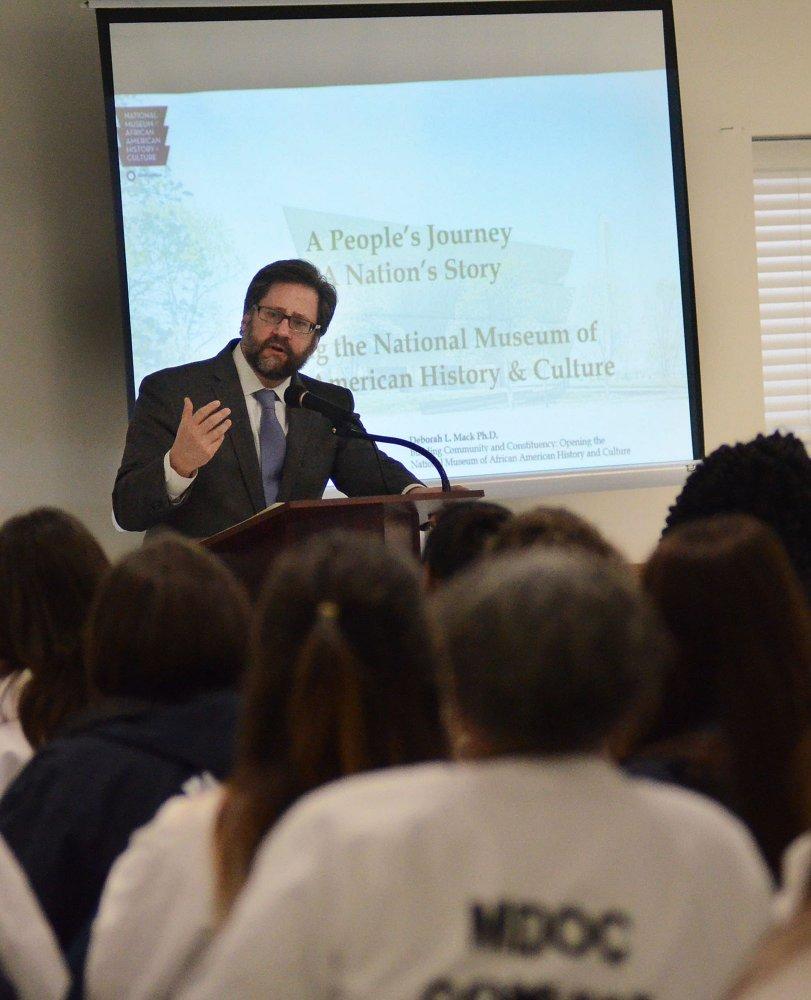

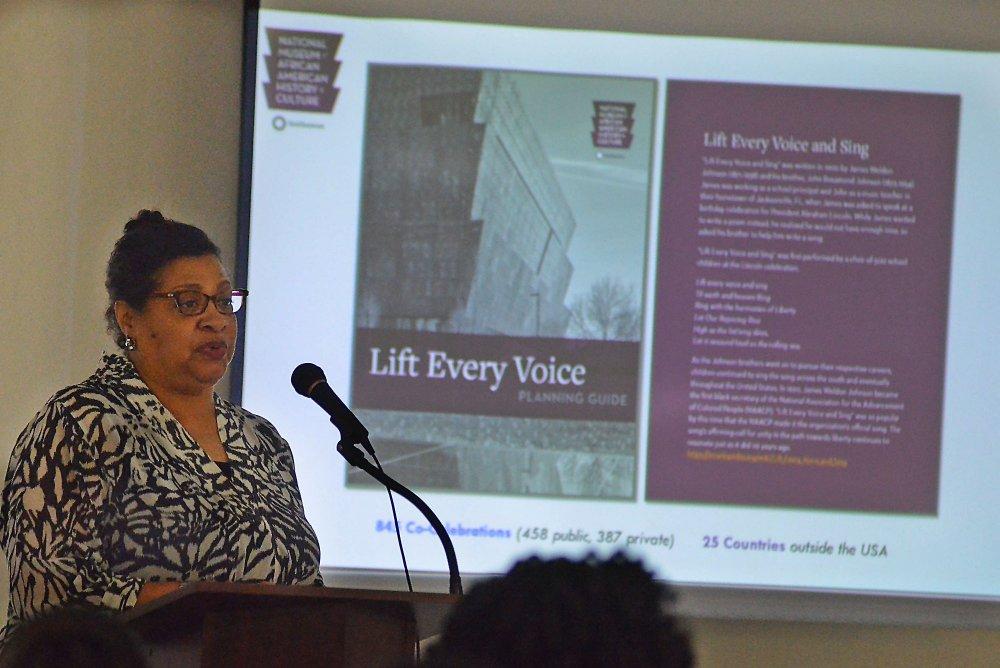

The Margaret Walker Center, based at Jackson State University, has for a half century devotedly pursued its mission of collecting, cataloguing, and diffusing information on the African-American history of the Magnolia State. In no other state is such a mission more integral and poignant, for Mississippi’s history is punctuated by the blood, sweat, and tears of slavery, Reconstruction, and the civil rights movement. Revealingly, the nation’s commemoration of African American history is in and of itself a riveting story. It is thus wonderfully fitting that the Margaret Walker Center, with the aid of a grant from the Mississippi Humanities Council, was able to bring that tale to Mississippi by way of the traveling Smithsonian Exhibition “A Place for All People,” an overview of the creation of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. The Center moreover arranged the unique opportunity for the exhibition to be displayed in two Mississippi prisons, the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl and the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, for the benefit of inmates who are too often denied access to the humanities. Female inmates at Central Mississippi were furthermore able to hear a presentation from NMAAHC associate director Dr. Deborah Mack, in marking of the exhibition’s set-up. “I appreciate everyone who was involved in the process to bring the exhibit to the Mississippi Department of Corrections,” Commissioner Pelicia E. Hall said. “It gave us a unique chance to feel involved in the museum. It also provided an educational opportunity for our offenders and staff. It’s important to understand where we have come from, where we are now and where we are going.”

In a testament to the exhibition’s success, in December 2017 NEH Senior Deputy Chairman Jon Parrish Peede, a Mississippi native, visited the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility to view A Place for All People. In remarks, Peede touched on the importance of the humanities in benefiting underserved populations. He noted in particular how A Place for All People, as supported by the Mississippi Humanities Council, is an outstanding example of how novel state humanities programming can make a difference in the lives of otherwise overlooked audiences.

Eastward across the state line and into the Yellowhammer State, The Alabama Prison Arts + Education Project is a prisoner learning program of the front line. Conducted under the auspices of Auburn University, and supported by the Alabama Humanities Foundation, instructors conduct classes for inmates at various correctional facilities covering a range of topics. Literature, mathematics, history, and psychology are presented by experienced instructors to these unique students, who after extended detachment from society are often enthusiastic learners. Lessons direct inmates’ efforts toward productive ends, boost their self-worth, and offer a tangible pathway for post-prison life. Comprehensive studies have concluded that prisoners exposed to classroom education are significantly less likely to return after release.

Special programs pioneered by the Alabama Project included classes taught by veterans and tailored to their fellow service members who are serving time. Such formats demonstrate how special connections can be made between inmates and those in “outside” society. The opportunity to serve as positive examples to their families and friends also contributes to prisoners’ positive change in outlook.

Corrections officials, those most qualified to judge the effectiveness of in-prison programs, have spoken of the inmate education initiatives with favor. The United States Department of Education has recognized the Arts + Education Project as a model undertaking and encouraged its emulation by prisons nationwide. The self-evident satisfaction of teachers associated with the Project, in their marveling of their students’ pent-up desire to learn, demonstrate how the inmates are not the only ones benefiting in the classrooms.

For the inmates and officials of the Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility in upstate Michigan, the time-honored works of William Shakespeare may have appeared to have been in jarring juxtaposition with the prison environment. Such plays, however, and particularly inmates’ participation in them, have lifted the spirits of many at the Facility. The program Shakespeare in Prison, with significant support from the Michigan Humanities Council, has introduced a novel forum of self-expression for these imprisoned women that at once improves their self-worth and inculcates valuable social skills for their future life on the outside.

Working with experienced theater instructors, the inmates spend several months learning acting skills and rehearsing for the production of a Shakespeare play. In the process these eager thespians develop teamwork skills, absorb the delights of some of the greatest work of Western literature, and hone their confidence in public presentation. According to the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, participants in the program have an impressively low 7.4 percent recidivism rate (compared with a national rate of 67 percent). The weeks of preparation are crowned with the enthusiastic reception these women’s plays regularly receive from their fellow prisoners. The most precious reaping from the Shakespeare program is the expansion of these women’s visions of what they can achieve through their own diligence. With plans for extending the initiative to juvenile facilities, Shakespeare in Prison will continue to offer the incarcerated alluring new opportunities.

In its comprehensiveness of educational services to prisoners and their families, the Education Justice Project (EJP), backed by the Illinois Humanities, may be peerless. The project has ensconced itself in the Danville Correctional Center in Danville, Illinois as a veritable school, with all the trappings of extracurricular activities, tutoring, and even alumni relations.

Under the aegis of the College of Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the EJP orients itself to the world outside the prison as well as in. Through sponsored lectures and research, EJP officials elevate public awareness of prisoner education as a topic worthy of attention and engagement. Outreach to inmates’ families enables them to remain as critical partners in their imprisoned loved ones’ development. The tracking of the progress of inmate “graduates” of the program gives the still-incarcerated hope for lives of accomplishment after release.

At the Danville Correctional Center one encounters the same assortment of educational resources as would surely be found at the local high school. Math, writing, and English as a Second Language tutoring are offered to inmates willing to seek them out. A student radio station and yearbook provide outlets for enriching endeavors beyond the classroom. A library and computer lab enable inmates’ access to the first such services they may have had since their own school years while still on the “outside.” The Education Justice Project of Illinois gives a ladder to those prisoners earnestly seeking to redress their own past mistakes.

Young people, particularly those caught in unfortunate circumstances not always of their own doing, are at a precipitous point in their lives. Unanchored to any support system, troubled teenagers may risk incarceration. Propped by caring mentors, however, at-risk youth may cross a bridge into productive lives. The Great Stories Book Clubs, administered by the American Library Association and aided since 2015 by the National Endowment for the Humanities, strive to be one such steadying influence for troubled teens in communities throughout the United States. Educational specialists select books whose themes hold special relevance for those encumbered by deep life challenges such as poverty, parental neglect, and drugs. Through insights gleaned from the readings, and encouraged within a supportive atmosphere, young participants can discern new opportunities for self-advancement and acquire a healthy outlook on their individualized situations. NEH has supported the efforts of numerous libraries of all types and sizes to host The Great Stories Book Clubs. An estimated 30,000 people across forty-nine states have been touched by the programs over the past decade. Each club meeting holds out the promise of another young life spared the pain of time behind bars and instead redirected onto a path of hope.

For a number of decades across the twentieth century, the Norfolk State Prison in Norfolk, Massachusetts, offered a model of prison reform at its best. Inmates were given access to libraries, classes, and musical instruction, encouraged to develop their talents, and enabled to maintain connections with the outside community. As such, the prisoners of these years, from the 1930s to the 1960s, were prepared to build their sense of self-worth and become productive citizens once their sentences were served.

The standout example of this reformist philosophy was the prison’s debate team. For many years eminent student debaters from Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton and Harvard made their way to Norfolk to contest the inmates’ team and were just as likely as not to return to their ivy-cloaked towers in defeat. The story of these prisoner debaters, which seems tailor-made for a moving tale of redemption, has surprisingly been forgotten, even in Norfolk itself. The recapturing of this stirring chapter has been undertaken by researchers associated with the Norfolk Historical Commission, aided by a $10,000 “Liberty and Equality” grant from Mass Humanities. Scholars are still close enough in time to that bygone era to be able to converse with those who were actually connected to the team. Oral history interviews have accordingly been conducted with former prisoners, team coaches, opponents, and spectators to entrust into the official record the memory of these unique debaters. All interviewees recall a period when the psychological barrier between the prison and the community was malleable enough to allow the exchange of goodwill in both directions. The planned translation of this matchless oral history into a book and radio documentary will help spread the story of the Norfolk State Prison debate team to audiences in the Bay State and beyond. For those interested in the cause of prisoner education today, there could scarcely be a more reaffirming example.

For many prisoners, the most painful rupture which they are compelled to make from society is the one with their children. Layers of separation, by way of physical walls and lost time, impinge on this most precious of relationships as the parents serve their debts to society. New Hampshire Humanities, in collaboration with the state Department of Correction’s Family Connection Center, offers incarcerated parents and their children a bridge over this divide through their innovative Connections reading program. With trained discussion facilitators, groups of prisoners read and reflect on various works of literature during scheduled sessions at their correctional facilities. Inmates are recorded reading the books out loud, which are then shared with their children who are simultaneously undertaking the same book at home. As such, incarcerated parents and their children undertake a common project, and nurture an indelible bond which overcomes all barriers standing between them. From musings on the U.S. Constitution among mothers to a pondering of children’s literature among fathers, the Connectionsprogram of New Hampshire Humanities has given imprisoned parents, and their children on the outside, a basis of hope as they travel their uniquely difficult journey together.

State humanities councils in other regions have imprinted their own marks on prisoner education projects in their respective communities. Maryland Humanities, by way of their standout One Book, One Maryland author lecture series, arranged for New York Times journalist Warren St. John to discuss the constructive role of prison libraries in benefiting incarcerated populations. In the Green Mountain State, Vermont Humanities similarly sponsored a talk by Professor Ilan Stavans on his innovative program Shakespeare in Prison, where a combination of inmate and Amherst College students contemplate the immortal words of the Bard together in the same classroom, to the enrichment of both.

According to the United States Bureau of Justice Statistics, 0.91 percent of Americans are currently incarcerated. This sizable population, forced to live on the margins of their communities, has reserves of potential which have been overlooked for too long. Prisoner education efforts, backed thoroughly by numerous state humanities councils, have valiantly and compassionately unlocked the unrealized abilities of society’s condemned and brought them into the sunshine of fulfillment. Reading the great books, writing stories, and performing plays under the guidance of caring professionals, open new vistas of possibilities for inmates as they come to appreciate their own capabilities and forge the personal connections that will help their post-prison community readjustment. As one Mississippi inmate said, “We are anxious to do whatever it takes for an education. We are eager to learn and want to do better.” For the transformational impact these humanities programs can have on lives, prisoner education programs represent a sound investment in the drive to reintegrate those forgotten Americans back into society.