From Chopin to Public Enemy

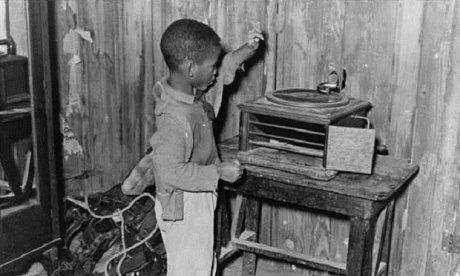

Child playing a phonograph in a cabin home. Transylvania Project, Louisiana.

Russell Lee, U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs, Library of Congress

Child playing a phonograph in a cabin home. Transylvania Project, Louisiana.

Russell Lee, U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black & White Photographs, Library of Congress

Some people can wax philosophical about a CD.

Once, when a friend asked him to explain the subject of the book he was writing, musicologist Mark Katz turned to his collection of compact discs. “Opting for a dramatic approach,” Katz recalled, “I pulled a CD at random from a nearby shelf and brandished it in front of me,” proclaiming that it had “changed the way we listen to, perform, and compose music.” The friend looked puzzled. “That did?“ he asked. “Yes!” replied Katz emphatically. Apparently unconvinced, the friend restated his question, “Van Halen changed the way we listen to, perform, and compose music?” Realizing his error—he of course was talking about the medium, not the artist—Katz generously affirmed, tongue planted firmly in cheek, that Eddie Valen Halen, David Lee Roth, and the rest of the iconic ‘80s band that took its co-founder’s name may indeed have had an outsized impact on the world of music, a point that undoubtedly has endeared him to “hair metal” aficionados everywhere. “But,” he wrote, “that was not my point” (Katz, Capturing Sound, 1).

“At its broadest,” Katz writes, the thesis of his book Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music is that “the technology of sound recording, writ large, has profoundly transformed modern musical life” (1). Recordings have changed, in very remarkable ways, people’s habits of listening to and composing music. Consider, for example, the early-twentieth-century American family that buys its first new Victrola, cranks it up, and is treated to an almost magical recorded rendition of a Chopin waltz or a Beethoven symphony, pieces that in bygone days listeners could only have appreciated live. Not only could listeners “play the same pieces over and over again without change” with the benefit of the Victrola, Katz points out, but they also had the power to decide “what they were to hear, and when, where, and with whom.” Or, shifting eras, muse for a moment on the ins and outs of digital sampling. Skillful hip-hop artists have repurposed and repackaged bits of earlier musical recordings to make new recordings, expressing new ideas. As Katz puts it, the “rich and complex” practice of sampling has challenged “our notions of originality, of borrowing, of craft,” while doing something even more fundamental, namely reorienting our most basic notions about musical composition. “Composers who work with samples,” writes Katz, “work directly with sound, thus becoming more like their counterparts in the visual and plastic arts.” In this light, the musicologist’s use of a quote by Chuck D., the frontman of socially-conscious rap group Public Enemy, seems particularly apropos: “We approach every recording like a painting” (175-176).

Capturing Sound, which won the Sally Hacker Prize from the Society for the History of Technology, is one of a growing number of books whose publication has been underwritten by a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Challenge Grant to the American Musicological Society (AMS). Starting with a $240,000 offer from NEH, AMS was able to secure four times the amount of the original grant in nonfederal gifts for a total of $1.2 million, which it invested in an interest-bearing endowment. The endowment income will provide publication subventions for important work on the study of music far into the future, particularly for younger scholars who can especially use the support. “In music, as in other humanistic disciplines, the mark of the emerging scholar is the first book, a milestone publication that refines and develops the research contained in the dissertation,” comments AMS president Anne Walters Robertson. “Yet, increasingly over the last decade, young professors in our field have found themselves in a kind of ‘Catch 22:’ they know they need to publish a book in order to be promoted, and yet publishers are wary of taking on first books. The problem is especially acute in music because of the cost of setting musical examples and other technical materials. We are gratified that we’ve been able to offer concrete assistance to our younger members, who represent the future of our Society, at one of the most vulnerable points in their careers.”

For more information about Capturing Sound, click here. To learn more about the AMS subvention program, go here.