The Three-Cornered War: A Q&A with NEH Public Scholar Megan Kate Nelson

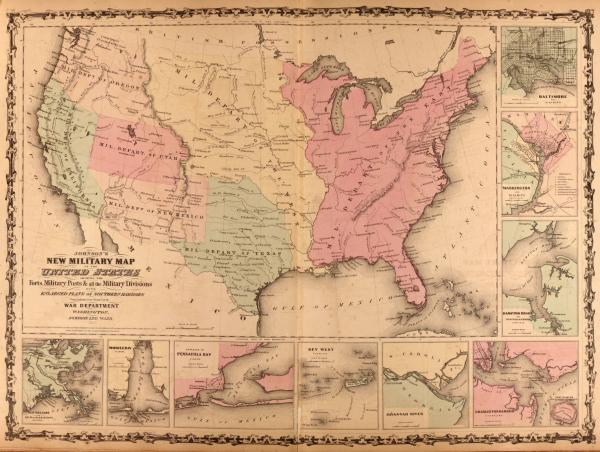

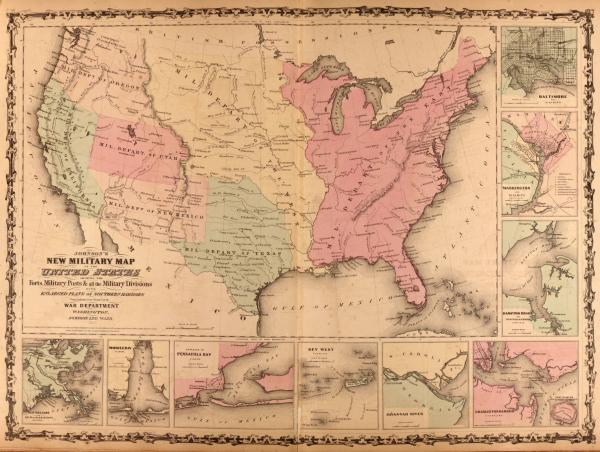

The Union Army’s organization of the US in 1862 from Johnson’s New Illustrated (steel plate) Family Atlas (New York: Johnson and Browning, 1862)

Provided by Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division (G1019 .J5 1862)

The Union Army’s organization of the US in 1862 from Johnson’s New Illustrated (steel plate) Family Atlas (New York: Johnson and Browning, 1862)

Provided by Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division (G1019 .J5 1862)

When it comes to Civil War history, the battles at Shiloh, Antietam, and Gettysburg are the most well-known episodes of America’s great divide. However, there are landscapes of the war that often go unappreciated in their historical importance. For this reason, NEH Public Scholar Megan Kate Nelson looks past the Mississippi River in The Three-Cornered War: The Union, The Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West (Scribner, 2020). Nelson creates a mosaic of the experiences of the Civil War beyond the Mississippi through the stories of individuals. She describes the vast West being eyed by both the North and South as a source of wealth to fund the war. For the South it was also to be their future “empire of slavery.”

The Three-Cornered War tells the stories of soldiers of both the Union and Confederacy, the wife of a general, a frontiersman turned commander, a federal land surveyor, an Apache war chief, and a young Navajo woman. The Battle of Valverde and the subsequent Battle of Glorieta Pass in 1862 are the explosive meeting points of their stories, and they are also pivotal moments in the conflict for the West at large. Nelson’s work, a finalist for the 2021 Pulitzer Prize in History, also contributes to the story of expanding America as her accounts of the battles are set against the backdrop of the birth of Arizona and the adolescence of New Mexico.

I talked with her about her research and about the role of the West in the war.

What brought you to the topic of the Civil War west of the Mississippi River? And why did you focus on these specific individuals?

When I was researching my previous book (Ruin Nation, 2012), I was reading a lot of general Civil War history. In the course of that reading, I found out that there were battles between Union and Confederate armies in New Mexico Territory in 1862. I was shocked. I grew up in Colorado, and had never heard of these battles, or the fact that Colorado soldiers played an important role in gaining control of the West for the Union. And as a historian, whenever you find out something you never knew about your topic, it lights a fire. I wanted to know what had happened in the Civil War West, and why.

Pretty early on I discovered that the war in the far western theater was incredibly complex, and involved many different communities, across vast distances of the high desert. I thought a lot about how best to tell all of these stories, and to convey how interrelated these communities were. I hit upon the strategy of multi-perspective narrative, rooting the book in the experiences of nine people. All nine of them played important roles in shaping the war in the West, and they each left behind enough source material for me to use in order to tell their stories. I wanted to give readers a real sense of the struggle for the West as it happened on the ground, and that larger vision of these communities as both diverse and interconnected.

Your focus on a federal land surveyor, John Clark, shows that the Union was not only trying to defend remote outposts but was also looking for possibilities of western expansion during the war itself. Do you intend for your book to say something about Manifest Destiny?

Yes. The historian Ari Kelman had already argued in his excellent book, A Misplaced Massacre, that we should see the Civil War as a war of imperialism. I knew from the sources I was reading about the conflicts in New Mexico that Union and Confederate officials saw the West as an integral part of their expanding empires. For the North, the region was central to their vision of an empire of free white labor, a West filled with farmers and ranchers and miners making the mountains and valleys productive. The South imagined the West as the center of their expanding empire of slavery, extending to the Pacific coast and then perhaps moving south into Mexico and Latin America. Both of these visions necessitated the extermination or removal of the West’s rightful landowners, Indigenous communities across the region. And during the Civil War, the Union and the Confederacy fought one another and various Native groups in order to make those imperial visions manifest.

You point out that the earliest military success that the Confederate states had was in New Mexico Territory. So why does their victory at the Battle of Manassas get all the attention?

Well, the eastern theater has always hogged all of the attention, during the Civil War and afterward, hasn’t it? For good reason: The largest armies of the Union and the Confederacy were fighting it out in Virginia, all within a one-hundred mile stretch between Washington, D.C., and Richmond. And the largest population centers were in the east, a reading public that wanted to know about what was happening in their own backyard. To them, New Mexico Territory seemed very far away.

But the early Confederate successes at Mesilla/Fort Fillmore in July 1861 were much more important than Civil War Americans even knew. They changed the map of the Confederacy, extending its western border to the Colorado River. They encouraged a larger army of Texans to follow and try to take New Mexico Territory, which was a gateway to the larger West. The battles that followed in February and March 1862 (in which the Confederates were not so successful) determined who would control 40 percent of the nation’s landmass, have access to the Santa Fe and the Overland Trail, and gain the economic benefits of the gold mines of the Sierras and Rocky Mountains, and the deep water ports of the Pacific.

These battles also changed the future of the West by bringing a much larger U.S. Army into the region than had been garrisoned there before. These soldiers, originally mustered into the army to fight Confederates, then fought campaigns against Native communities in the Southwest.

After the Battle of Valverde, Confederate forces thought they well on their way to conquering the American West. Then came their defeat at Glorieta Pass and their realization that they had failed. Do you think the West was anyone’s to claim or conquer between 1861 and 1865?

White Americans definitely believed that the West was theirs to claim. Although technically the federal government (and during the war, Union and Confederate governments) recognized the sovereignty of indigenous peoples across the region by making treaties with them, the content of those treaties suggests that white Americans believed that ultimately, they had the right to take whatever they wanted from western lands. And as the readers of The Three-Cornered War will come to understand by coming to know Union General James Henry Carleton, the Union Army and the Republican administration pivoted during the war to the rejection of treaty making and the assertion of a new kind of Indian policy: make war upon Native peoples first, force them to surrender, and then remove them to reservations where they could be surveilled, controlled, and “civilized.”

Most people think that the conflicts between U.S. Army and Native people happened after the Civil War, but you demonstrate that they were occurring from late 1862 on. Do you want your book to change the starting date of the “Indian Wars”?

Absolutely. Whenever historians expand the geography of the Civil War, we expand and change the chronology. For many residents of the Southwest (Native peoples, Hispanos, and Anglos), the Civil War was both a continuation of a long history of violence in the region, and a watershed moment in which the character and intensity of that violence changed. The American federal government fought Native peoples here from its first arrival in Indigenous homelands in the 1840s and continued to do so through the Civil War and into the 1880s. In the desert Southwest, the Civil War was an Indian War.

Can you define and describe Bosque Redondo and the Long Walks?

In the fall of 1862, when General James Henry Carleton arrived from California and took command of the Department of New Mexico, he turned the full power of the Union Army on Native peoples in the region. He initiated campaigns against Mescalero and Chiricahua Apaches and Navajos. His orders to his officers suggested a war of extermination, but his real goal (per this new Union Indian Policy) was to force their surrender and remove them from their homelands and to a reservation along the banks of the Pecos River in central New Mexico called Bosque Redondo. When Kit Carson, Carleton’s favorite officer, succeeded in forcing more than 8,000 Navajo men, women, and children to surrender beginning in the winter and spring of 1864, the Union Army sent them on a 400-mile march to Bosque Redondo, a series of journeys that the Navajo people refer to collectively as the Long Walk. Carleton chose the site for the reservation himself, and he chose poorly. Bosque Redondo had terrible soil and very few trees, and the water quality of the Pecos River was awful. The reservation (which was, in reality, a prisoner-of-war camp) was a disaster from the start, and Carleton’s mismanagement resulted in a 20-25 percent Navajo mortality rate. The conditions there were so bad that by the time Navajo headmen negotiated their peoples’ return to their homeland in 1868, they were calling it Hwéeldi (Land of Suffering).

The Three-Cornered War addresses the landscape of the American Southwest and its impact on the events of the book. Based on your description, you seem to have treated the locations as almost first-hand sources. Would you use this approach for other projects or is it unique to this one?

Yes, many readers have suggested to me that the southwestern desert is the 10th character in the book, and I absolutely agree. I am trained as an environmental historian and an interest in unloved and challenging landscapes has shaped all three of my books (the first two are about swamps and ruins, respectively). I have made site visits as part of my research process for all three of those projects; you can learn so much from looking at and being in the places where historical events took place. The high desert is a particularly extreme environment, especially in the context of warfare. The failure of the Confederates, the victories of the Union, and the sustained resistance and suffering of Native peoples in the Civil War west are all attributable to each community’s ability to control the landscape, and natural resources.

What’s next for you?

I am already working on my next book. It is called This Strange Country: Yellowstone and the Reconstruction of America. It tells the story of the 1871 scientific survey to Yellowstone and how it led to the Yellowstone Act of 1872 (which created the first national park in the world), rooting these events in the history of Reconstruction.

Megan Kate Nelson received a Public Scholars award (FZ-256405-17) to support her work on The Three-Cornered War: The Union, The Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West (Scribner, 2020). Nelson is an independent researcher and scholar living in Massachusetts.

The Public Scholars program supports well-researched books in the humanities written for the general public. For more information on the NEH Public Scholars program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact publicscholar@neh.gov with questions.