Phantom Records: A Two-Part Series on Searchability and Records in Chronicling America, Part 2

In the previous blog post in this series, I discussed the search function of the National Digital Newspaper Program’s (NDNP) website, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, using variants from Library of Congress Name Authority Files (LCNAF). That blog post focused on how to use a person’s LCNAF record to refine search terms, and how to utilize the variant names within an LCNAF record to enable different avenues for research. I will continue this discussion of Chronicling America and LCNAF records, but this time using a direct example from my work as a summer intern for the Division of Preservation and Access, enhancing the LCNAF records for newspaper editors in the ethnic press. This record enhancement work builds on the work of previous intern Joshua Ortiz Baco, who wrote about his internship experience in “Title Essays, Linked Data, and the Ethnic Press” last summer. This summer, I continued where Baco left off in his record enhancement.

When NDNP state partners submit newspaper titles to Chronicling America, they provide much more than digitized images of newspaper pages. Coordinators also submit title essays, which are brief summaries of a given newspaper title’s history, including information about any prominent editors or reporters, and the role the paper played in the community it served. Over the summer, it has been my job to identify the editors named in title essays, research these editors, and compile the information necessary to create a new entry for the editor in the LCNAF record. One step in this process is to search the editor’s name in the LCNAF record, to see if the editor has already been assigned a name authority file. If so, then I make note of the existing LCNAF record. If the search for an editor’s name does not match any existing LCNAF record, then I use Chronicling America to find evidence of the editor’s work for the newspaper, and I provide a link to the digitized newspaper page as evidence of the editor’s role, a citation that will then be used by the Library of Congress staff to create the editor’s LCNAF record.

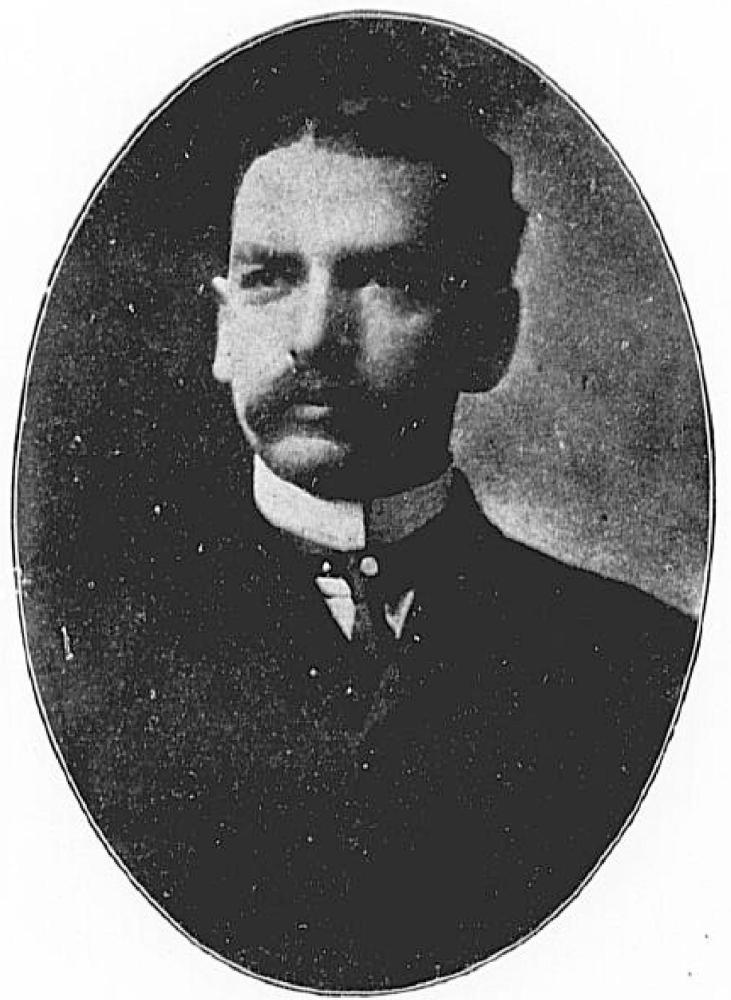

This record enhancement process allows me to “meet” so many fascinating figures in the nation’s history, including Samuel W. Starks, founder of the West Virginia paper the Advocate (1901-1913). The title essay for the Advocate describes the paper as part of the Black press, covering Charleston’s and West Virginia’s Black communities more broadly.

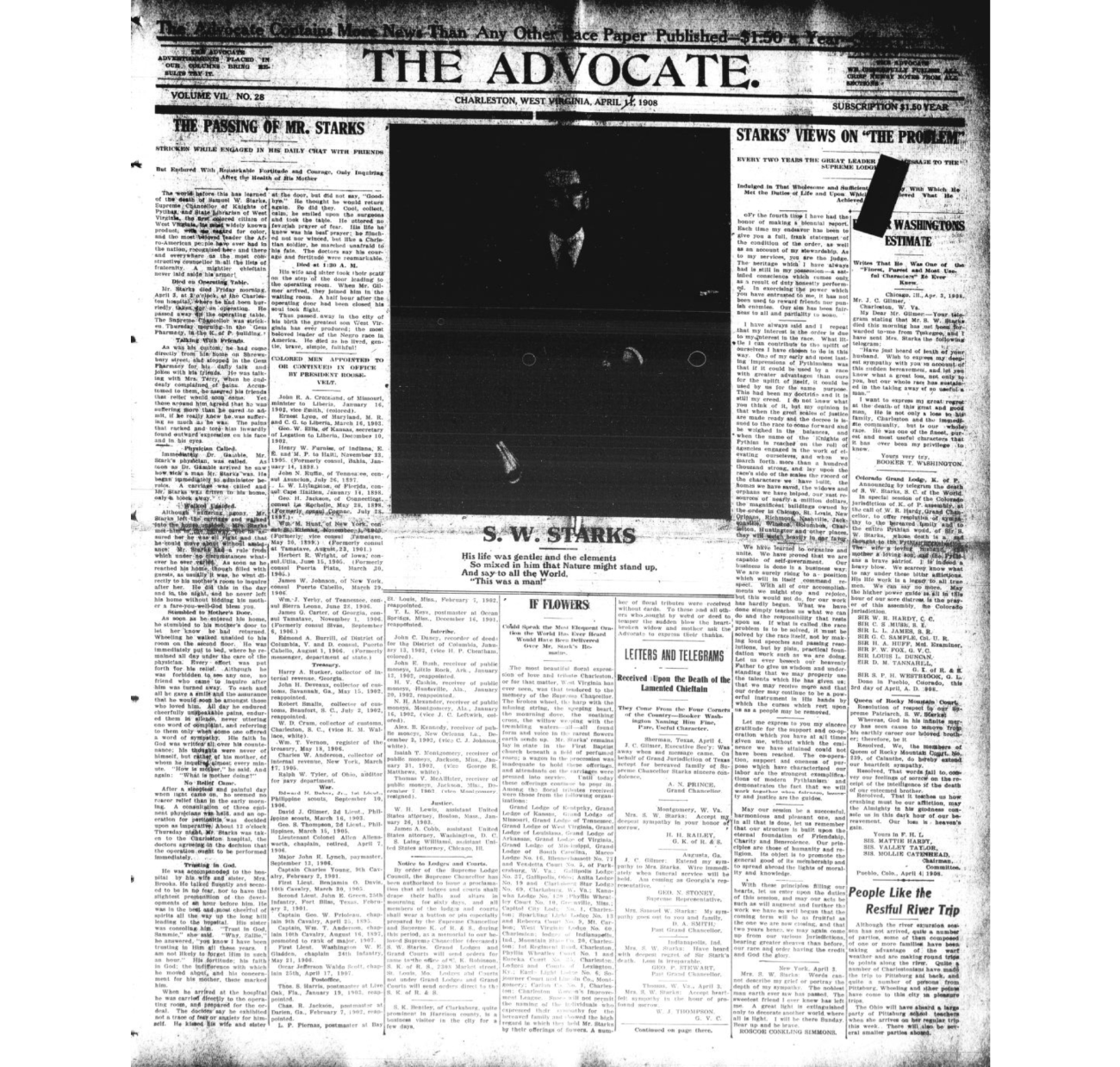

Founder Samuel W. Starks’s name is peppered throughout articles in early issues of the Advocate, mostly in reference to his prominent role as the state’s first Black state librarian as well as his election to lead a fraternal organization, the Colored Knights of Pythias. When Starks unexpectedly passed away in 1908, the paper covered his funeral proceedings and remembrances at length, including condolences from Booker T. Washington.

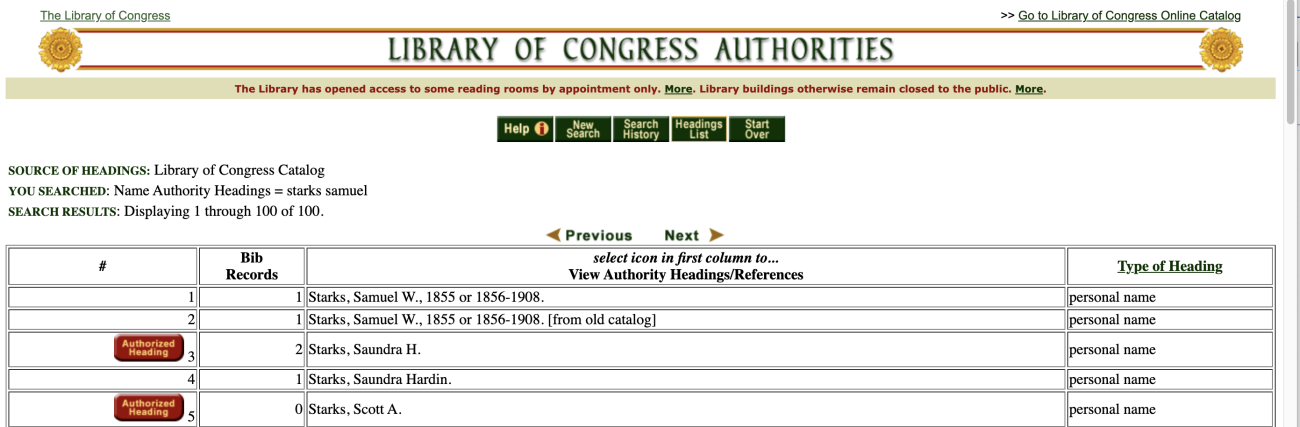

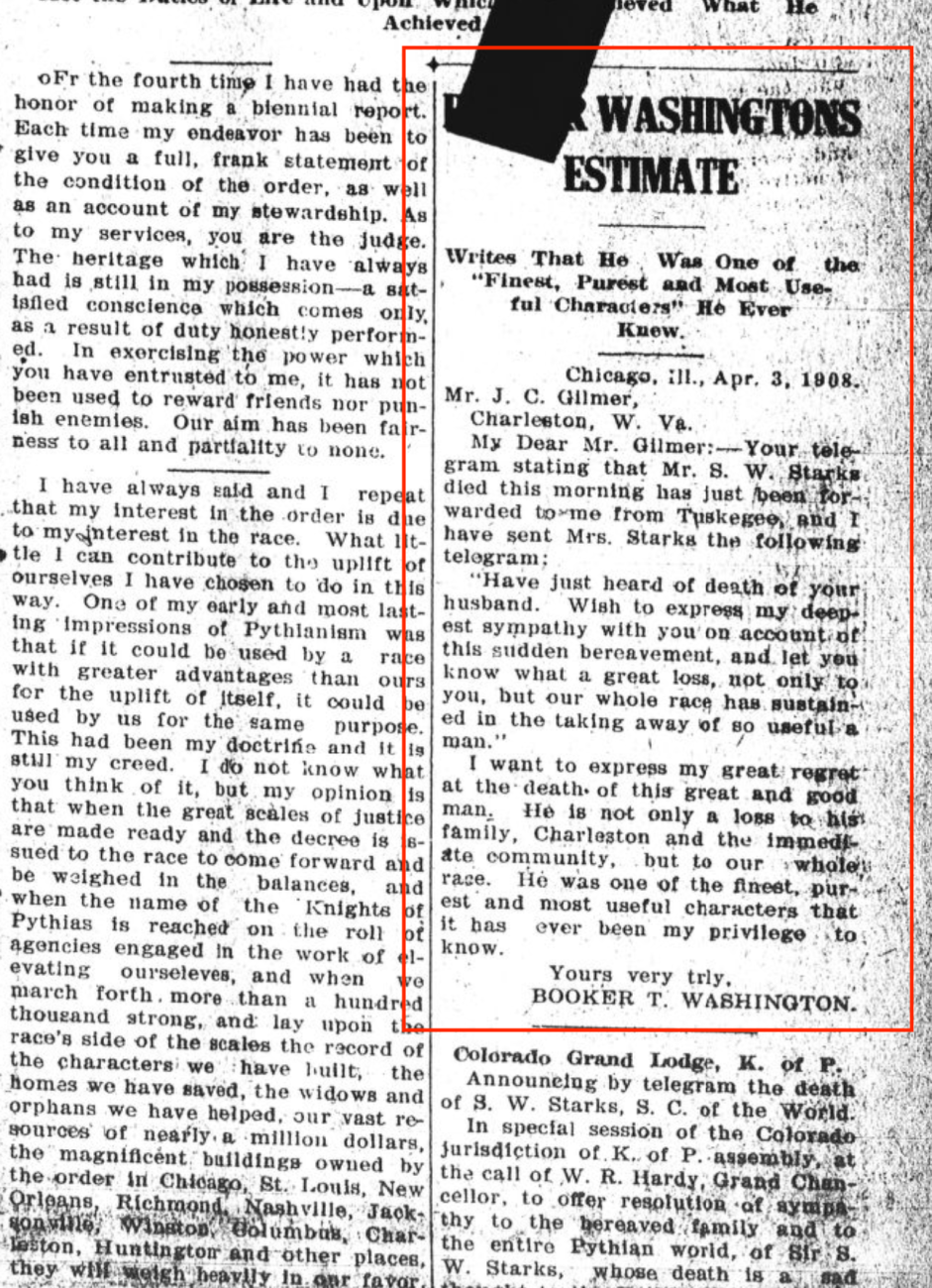

Starks played a prominent role in his local community, his state of West Virginia, and the nation’s history. How then can we ensure that those researching Starks’s life and works, as well as associated topics like editors in the Appalachian Black press, can find the resources available on Chronicling America? In my work with title essays, I searched for Starks in the LCNAF record. There, I found an intriguing entry:

The LCNAF record includes Samuel W. Starks’s name, associated with his birth and death dates, so clearly this is the correct Samuel W. Starks. But the LCNAF record also includes the notation “[from old catalog].” What does it mean for a reference to be in the “old catalog”? Does this mean that Starks’s record was “retired” at some point, for some unclear reason? If so, how then can we “revive” Starks’s record so that his name becomes part of the linked data connecting the Advocate to other resources about him online? Starks’s digital data trail includes his biographical information on the West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History website, the designation of his house on the National Register of Historic Places, as well as his Wikipedia and Wikidata pages. Additionally, what information was represented in the old catalog that could be hidden outside of the internet’s reach, in the world of material rather than digital collections?

I reached out to the NDNP partners at the Library of Congress with these questions, and the answer to my speculations was quite simple. According to the Library of Congress cataloging resources, the “[from old catalog]” note indicates a record that has not been maintained since the Library of Congress’s creation of its current catalog in 1999. The “[from old catalog]” notes appear in “several million older bibliographic records” that the LC incorporated in 1999 but did not fully verify, presumably due to constraints on time and budget. The LC resources page answered the root of my question. Library of Congress staff and I decided on a way to make special note of the editors who surfaced during my work with title essays and whose names match a LCNAF record “[from old catalog].” This solution will allow catalogers to retrieve Samuel W. Starks’s record “[from the old catalog]” and update his LCNAF record. Though this question is easily solved, the curious idea of Starks’s name lingering in print somewhere in library storage, covered in the dust accumulated since 1999, persists.

From a media archaeology standpoint, this case study is an example of what happens when records are updated from print to digital data, and what can be flagged and forgotten until a new round of record enhancement begins. Clearly, the “[from old catalog]” note is common enough to merit its own section in the FAQ page. From the perspective of African American history more broadly, this question also points to the necessity of enhancing the records for titles in the ethnic press, titles with editors who served their communities but who have not been properly represented in past catalog maintenance. The work of reparative record enhancement continues, and for now, Samuel W. Starks’s catalog record is on its way to being fully updated, complete with a verified entry into the LCNAF record, to serve as another piece in the constellation of information about his life, his work for the Black press in West Virginia, and the network of linked data that already exists about him online.

Jeannette Schollaert is a summer intern in the NEH Division of Preservation and Access and a PhD student in the English Department at the University of Maryland, College Park where she is completing a dissertation entitled, "Censors and Shouts: Technologies of Abortion in American Fiction."

![Close up of top-right side of previous image, featuring “[Booker] Washington’s Estimate” of Samuel W. Starks. The Advocate, 11 April 1908.](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2021-08/image%204_booker%20t%20washington.png?itok=mFkn5tSQ)

![Search results for Samuel W. Starks in the LCNAF record; Starks’s name appears with the designation “[from old catalog]”](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/2021-08/image%205_Starks%20LOC%20from%20old%20catalog.png?itok=L1IrLnPY)