Documenting Lost African-American Newspapers

Louisa Trott is an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville's Hodges Library, where she directed the Tennessee Newspaper Digitization Project.

Printed newspapers are not made to be saved. Their primary purpose is to deliver timely information so, once read, they are usually discarded or repurposed entirely. In the not too distant past, they might be used to light a wood stove or to insulate a home. Even after newspapers’ historical and cultural value was recognized by archives and historical societies in the nineteenth century, the effort to collect and preserve them was rarely systematic or inclusive. Collecting institutions sought “papers of record,” rather than the often shorter-lived serials from historically marginalized communities. This considerable oversight means that the newspaper productions of African Americans, Native Americans, and non English-speaking communities were preserved in far fewer numbers, and many were lost entirely. Not only individual issues but complete publication runs have been forgotten with little or no trace.

The U.S. Newspaper Program, a cooperative nationwide effort led by NEH and the Library of Congress between 1982 and 2011, enabled state partners to locate and catalog historical U.S. newspapers and preserve them on microfilm. Building on this program, the National Digital Newspaper Program has supported the digitization of select historical newspapers, providing access to them online through Chronicling America. Using metadata from these programs, the Library of Congress created the U.S. Newspaper Directory, which allows users to search for newspapers published in the United States since 1690. The directory also provides information about newspapers held at institutions across the United States, including location details, publishers’ names, and publication dates, as well as how and where to access print, microfilm, and digital holdings. The directory currently lists more than 157,000 titles. As extensive and impressive as the directory is, it is not a complete picture of American newspaper history. The directory draws on catalog records for extant items, and so reflects only the newspapers that have been collected, cataloged, and preserved by institutions.

Paramount to our selection process for the Tennessee Newspaper Digitization Project (TNDP) was the inclusion of a broad representation of political, ethnic, and geographical coverage. We made a concerted effort to identify newspapers from underrepresented voices, in particular, African-American newspapers. As project coordinator for TNDP, I was responsible for carrying out research to identify newspapers for the project’s advisory board to consider for inclusion. I began by searching catalog records from the Tennessee State Library and Archives and the U.S. Newspaper Directory. The directory lists a total of 37 African-American titles for Tennessee (pre-1923, per the project’s scope at the time), but closer investigation of the records showed that most had only a single or a few scattered issues. This was true of all the other 62 post-1923 titles. As I broadened my research, searching in nineteenth-century newspaper directories, bibliographies, reference books, dissertations, and other newspapers (see the list of works consulted below), I realized that many of the titles referenced in these resources were not listed in the directory because there were no extant copies; the directory provides records only for titles held in collections and cataloged. It became apparent that I was finding significantly more references to African-American newspapers than were listed in the directory. Even some of the most celebrated and historically significant titles such as Ida B. Wells’s Memphis Free Speech and Headlight has no known extant issues, and so does not appear in the directory.

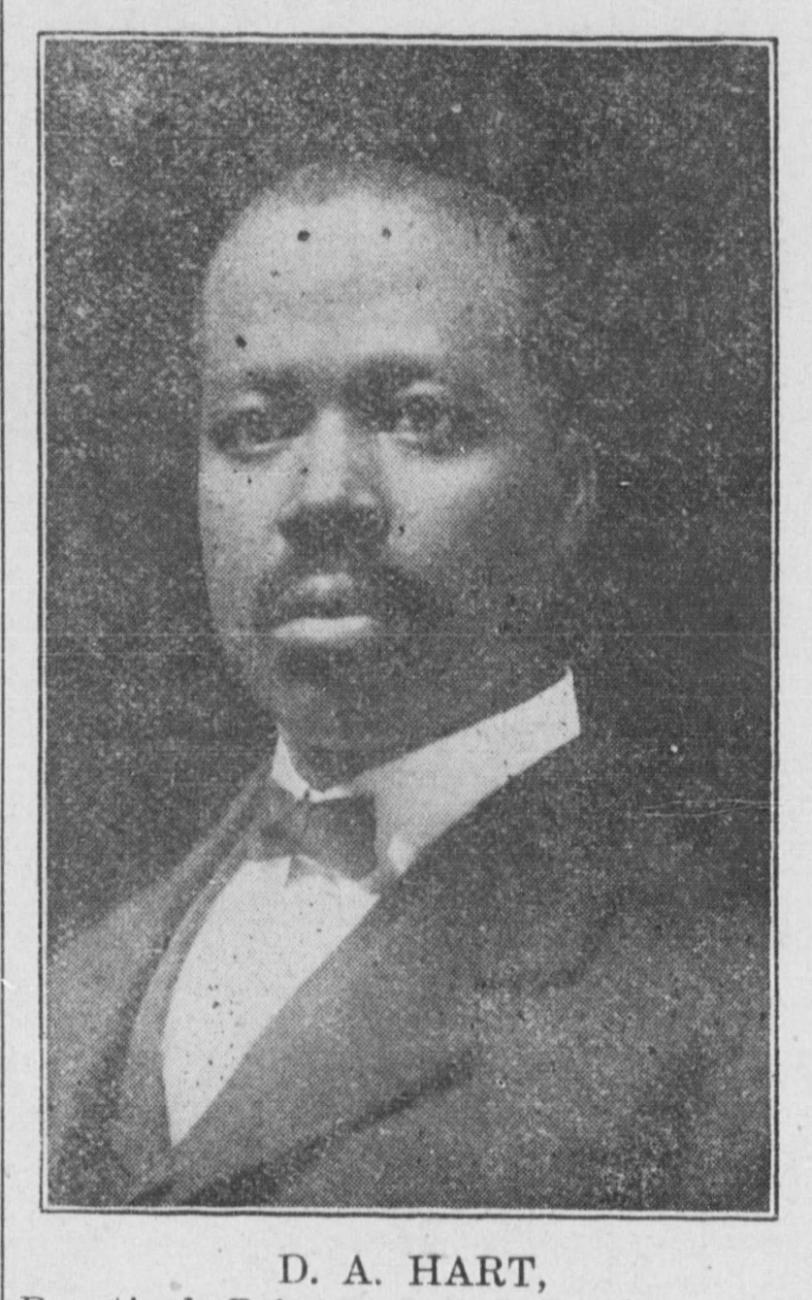

I created a spreadsheet documenting as much information as I could find about the newspapers from the various sources. The spreadsheet recorded the newspaper’s title, location, publisher, dates of publication, frequency, any additional information, and the source where I had found the information. The current total of African-American Tennessean newspapers in this list stands at 206 titles. Among this list are those that were considered “religious,” though they include much more than news from a particular church. They include more general news and information about African-American communities. In an article published in a supplement to the Nashville Globe on April 10, 1908, Dock A. Hart recognized the importance of the church printing houses in the distribution of news to the broader community outside of their congregations.

By documenting the existence of newspapers that have no known surviving copies, we can create a fuller picture of our newspaper history. This is particularly important for communities that are underrepresented in library and archive holdings. When a researcher searches the U.S. Newspaper Directory for African-American newspapers in Tennessee, they will not see a reflection of the true history of these papers in the state because so few survive. Documenting references to “lost” newspapers also helps libraries and archives with collection development. If they have information about titles that are missing, they are better equipped to track down “lost” titles, or to recognize a “lost” title if it is offered to their collection. Knowing that a title is missing, librarians and archivists can make efforts to locate issues and raise awareness among scholars, librarians, and the community. Collating and providing access to this information in one location (either at a state or, potentially, national level) will help build an even broader picture of our newspaper history and can help provide missing links or fill in some gaps in our newspaper histories.

A useful source for finding references and supplemental information on newspapers that have few or no extant issues is other newspapers from the same time period. Newspapers often refer to other newspapers, either when reprinting a story from another paper and citing it, or when mentioning another publication within one of its own pieces. These stories can often provide more information about the newspapers and the people behind them. The Nashville Globe ran a biographical sketch on its front page on January 31, 1908, about its manager, Dock A. Hart.

This piece tells of Hart’s career in the newspaper trade, and the Nashville Tribune, where Hart’s career began in the 1890s. There are only two issues of this paper listed in the U.S. Newspaper Directory, one from 1890 and one from 1891. However, another source (Brown, 1982) cites the Nashville Tribune’s publishing dates as 1912–13. A further search of the Nashville Globe reveals a story printed in the November 1, 1912, issue in which the Tribune is mentioned, along with its office location in the Johnson Building and its managing editor W. H. Young. As there are no extant copies of the paper from this time, there is no record of it in the U.S. Newspaper Directory.

Gathering and providing access to this kind of information about newspapers that once circulated but no longer exist helps us to see a fuller picture, with varying perspectives, of newspaper history in the United States.

Resources to discover references to lost newspapers:

Nationwide

- Rowell's & Ayer's American Newspaper Directories: a catalogue of American newspapers and a list of all newspapers from the United States and Canada

- Campbell, Georgetta Merritt. Extant Collections of Early Black Newspapers: a Research Guide to the Black Press, 1880-1915, with an Index to the Boston Guardian, 1902-1904. Troy, N.Y: Whitston Publishing Co., 1981.

- Danky, James Philip, and Maureen E. Hady., editors. African-American Newspapers and Periodicals: a National Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Henritze, Barbara K. Bibliographic Checklist of African American Newspapers. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1995.

- Potter, Vilma Raskin. A Reference Guide to Afro-American Publications and Editors, 1827-1946. Ames: State University of Iowa Press, 1993.

Regional

- Brown, Karen Fitzgerald. The Black Press of Tennessee: 1865-1980. PhD dissertation, University of Tennessee, 1982.

- Mooney, Jack., editor. A History of Tennessee Newspapers. Knoxville: Tennessee Press Association, 1996.

- Shannon, Samuel. “Tennessee.” The Black Press in the South, 1865-1979, edited by Henry Lewis Suggs, Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1983.

P.S.

As of April 20, 2022, we have received a fruitful response to this blog post, including new information about two Tennessee newspapers mentioned in a Washington, D.C., newspaper from 1884.

After sharing the NEH blog post with the Tennessee Library Association listserv, I received an email from Bill Dahnke from the Obion County Public Library in West Tennessee. Bill shared an article he had found in the Bee from January 26, 1884, (p.2, col.3) which mentions two then-new African-American newspapers from Tennessee (among others) – one of which was on our list, but the other was not! The New South was published in Union City, Obion county, a town which was also not represented on our list.

A further search across several historical newspaper databases and newspaper directories provided more information about the New South, as well as two short news items reprinted from the paper in other newspapers. We now know that the New South was a six-column weekly, owned and edited by P.F. Hill, a teacher in Union City. In August 1884, the newspaper’s name changed to the Royal Banner, published monthly, and was affiliated with the order of United Brothers of Friendship and Sisters of the Mysterious Ten. The Royal Banner is listed in Ayer’s directory in 1887, but it is not known when publication ceased.

Special thanks to Bill Dahnke for sharing the information that led to the discovery of these new titles.

![The Bee [Washington, D.C.], January 26, 1884, shared news of recently-launched African American newspapers, including two from Tennessee.](/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/2022-04/TheBee_18840126_p2_Announcement.jpg?itok=s-BAdYru)