Chronicling America and the Eskimo Bulletin: Recovering the History of a Residential Boarding School in Alaska

The National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) is a joint venture of the Library of Congress and NEH and represents one of the pillars of NEH’s funding programs. Formed in 2003 and granting awards annually since 2005, NDNP supports cultural heritage institutions in every state, including libraries, historical societies, and universities, to select, digitize, and deliver content from their newspaper collections to the Library of Congress. The result is an extensive and rich online database called Chronicling America with an accompanying interactive map and timeline that visualizes the geographic and temporal coverage of the aggregated content. Chronicling America makes freely available online a wealth of rare regional, historical, and at-risk public-domain newspapers published from 1690 to 1963. In 2022, the program achieved two significant milestones, marking 20 million pages freely available to the public and, with the recent inclusion of New Hampshire, having every state participate in the program.

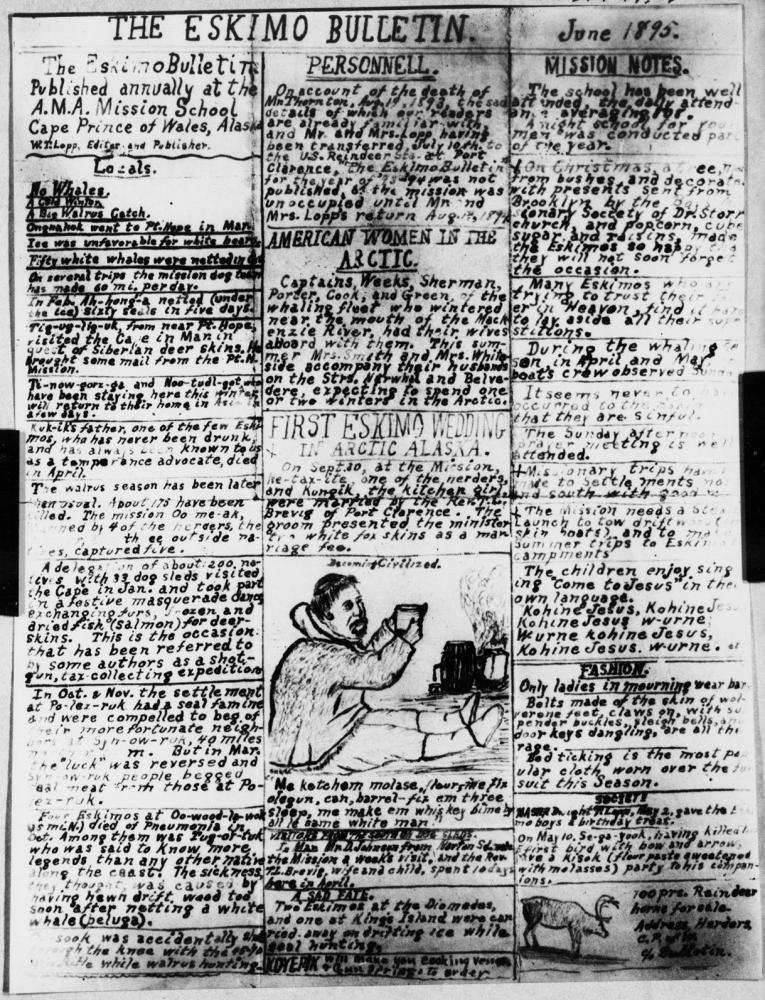

One newspaper that forms part of the Chronicling America collection is the Eskimo Bulletin (1893-1902). The term “Eskimo,” referring to the Native communities of Alaska and Arctic regions, is considered derogatory today and as indicated here, was employed by non-Native settlers. The Bulletin constitutes a record of the compulsory education system for Indigenous children that began in Alaska in 1867 following its territorial acquisition by the United States. Starting in 1819 with the Indian Civilization Act and lasting until the 1970s, Indian boarding schools were created across the nation by the United States government. These residential schools removed Native children from their families and isolated them geographically and culturally while enforcing English-only education and implementing cultural assimilation initiatives. According to the Department of the Interior, “the purpose of federal Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children by forcibly removing them from their families, communities, languages, religions and cultural beliefs. While children attended federal boarding schools, many endured physical and emotional abuse and, in some cases, died” (DOI, 2022).

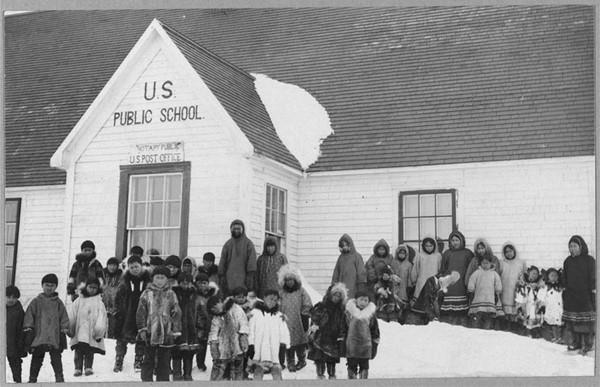

Though the Eskimo Bulletin does not record such abuse, we can presume that life was hard, very hard, for the students forced to attend. The Cape where the school was located and from where the Bulletin was published was named Nykhta by the Yup’ik Indigenous peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska. The white settlers renamed it “Cape Prince of Wales,” or simply “Wales,” and as the snow-covered roof on the schoolhouse in the above photograph demonstrates, winters were long and weather severe in this northern outpost.

The title essay, or accompanying description, of the Eskimo Bulletin provided by the Alaska State Library Historical Collections, reveals the paper’s genesis:

The Eskimo Bulletin was a yearly publication produced at the American Missionary Association’s mission school at Cape Prince of Wales. The paper was edited by William T. Lopp and published by both Lopp and Harrison R. Thornton, who were both missionaries and teachers. The first issue was published in May 1893 and was handwritten, although it was reprinted in type by another newspaper. Thornton was killed later that year, and Lopp was transferred to the U.S. reindeer station at Port Clarence. Therefore, no issues were published again until 1895 when Lopp returned to Cape Prince of Wales. The paper claimed to be the only yearly paper in the world. The Bulletin focused on local news and issues affecting Native Alaskans.

The Bulletin, published in the Cape Prince of Wales by the mission school, provides insight and commentary from the position of settlers, missionaries, and administrators of the boarding school system in Alaska. The newspaper is a rare primary source for researching and understanding the difficult and traumatic boarding system, but what is missing are the voices of the Native students.

In the absence of Native voices, images from the Library of Congress’s collections help recover this history and make the students visible, standing in front of the Cape Prince of Wales residential school:

Photographs, newspapers, records, family memories (written and oral) . . . all of these and more will be needed for us to begin to uncover, recover, and understand the experiences of these children taken from their homes and forced into these schools. To aid in efforts to make resources such as these more available, in June 2021, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to recognize the residential boarding school policies and to create a pathway to deal with the impact of these past and intergenerational traumas. In April 2023, an inter-agency partnership between the Department of the Interior and NEH expanded the initiative to provide $4 million in support of furthering this work in the form of collecting oral histories and the digitization of records from the United States' system of 408 federal Indian boarding schools. The initiative will create a permanent oral history collection, documenting the experiences of the generations of Indigenous students who passed through the federal boarding school system. These digitized collections, in conjunction with ongoing documentation through oral histories of survivors, will assist in amplifying the voices and center the experiences of Native children and their descendants who were subjected to this troubled legacy.