3D Humanities: Digital Visualizations Promote New Research and Discourse

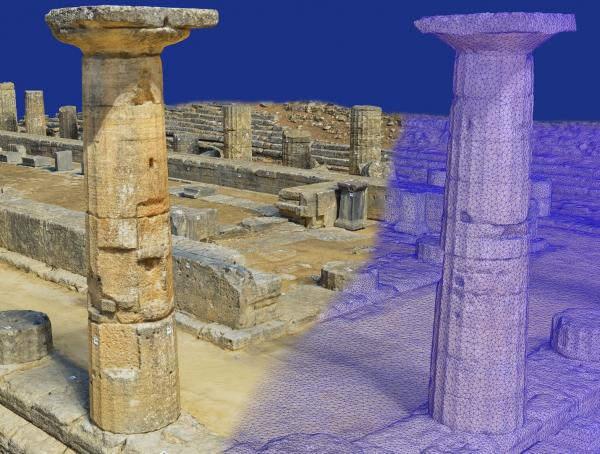

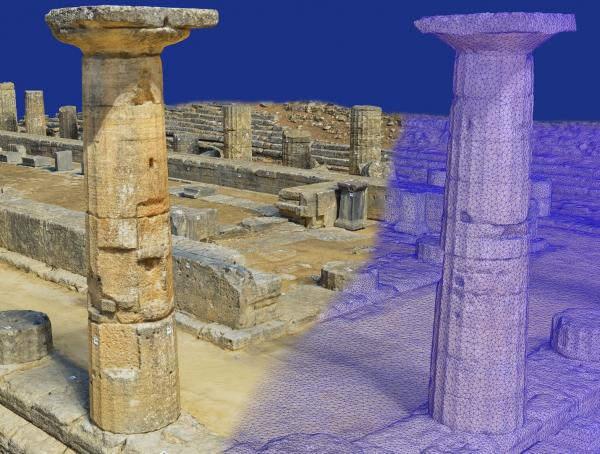

Image of Philip Sapirstein’s model of the temple of Hera at Olympia, revealing the mesh detail.

Courtesy of Philip Sapirstein

Image of Philip Sapirstein’s model of the temple of Hera at Olympia, revealing the mesh detail.

Courtesy of Philip Sapirstein

Several of the projects recently funded by NEH-Mellon Fellowships for Digital Publication feature digital 3D visualizations as part of their scholarly contributions. Broadly, digital 3D visualizations refer to digital images or graphics that allow for user manipulation and interaction across the three dimensions of space. A range of technologies can be used to create interactive 3D visualizations and can be tailored to the needs of the researcher and scope of their project. The three NEH-Mellon grantees introduced here exemplify this and employ a variety of technologies according to the diverse research questions and approaches of their projects.

We spoke with Philip Sapirstein, Elaine Sullivan, and Heather Richards-Rissetto about the advantages of digital publication, the role of 3D modeling and visualization in their projects, and how they are impacting research being done in the humanities.

Reassembling the columns of the Temple of Hera at Olympia

Philip Sapirstein is Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto in the Anthropology and Art History Department. 3D modeling is central to his project, The Ancient Greek Temple of Hera at Olympia: A Digital Architectural History (FEL-257634-18), which considers how this ancient temple’s columns were built and introduced the Doric style of architecture. To reconstruct the temple from fragments scattered across the site, Sapirstein used automated photogrammetric modeling software, which uses photographic recordings to create a 3D model. One major advantage of this digital recording technology is that it produces high-quality images in a fraction of the time compared with “analogue” methods (such as hand-drawing). In so doing, the technology has allowed Sapirstein to devote more time to “creative thinking, exploring the site, and investigating questions.” Moreover, Sapirstein notes that in preparing the site for the recordings which were used to create the model, he noticed features that he might otherwise have missed had he been focused on producing a technical drawing of the structure.

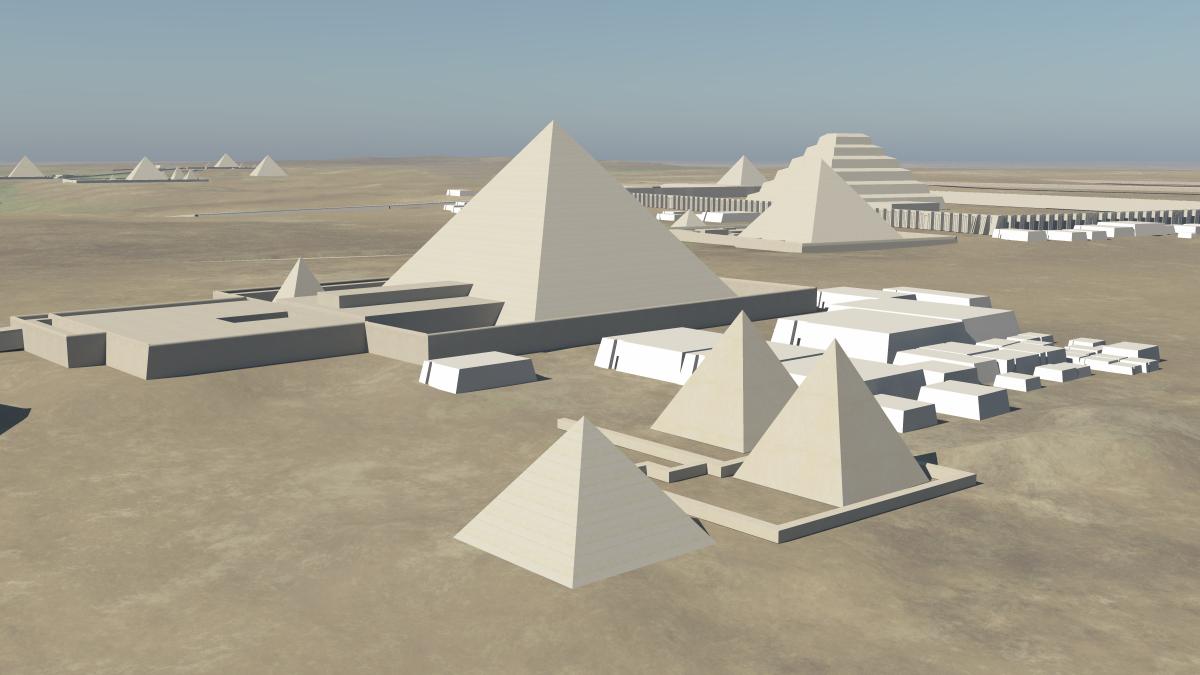

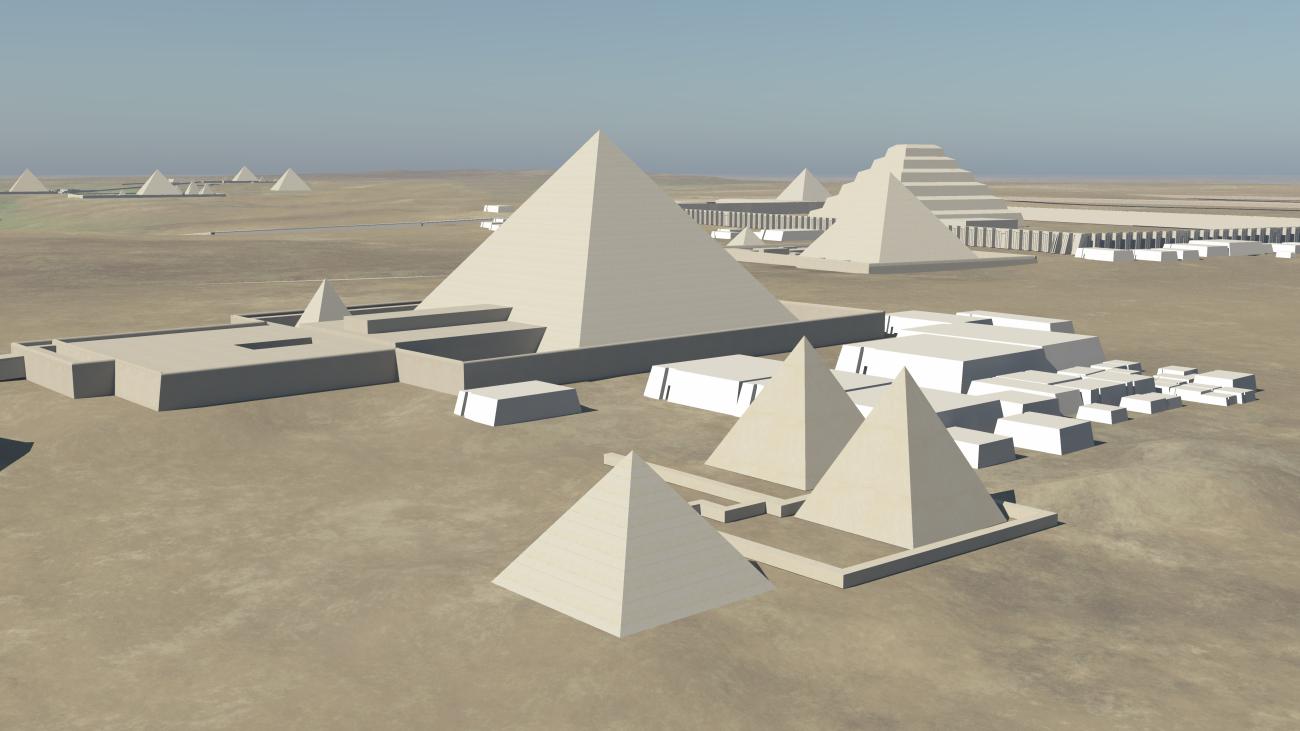

Visualizing the pyramids and tombs at Saqqara

Elaine Sullivan, Associate Professor in the History department at the University of California-Santa Cruz, employed 3D visualization technology for her digital monograph on the ancient necropolis at Saqqara, Constructing the Sacred: Visibility and Ritual Landscape at the Ancient Egyptian Necropolis of Saqqara, 2950-350 BCE (Stanford University Press, 2020). During her fellowship (FEL-257873-18), she used 3D and GIS (geographic information system) software to reimagine the array of monumental structures over almost three thousand years at the large ancient cemetery—a necropolis or “city of the dead”—at Saqqara in Egypt. The 3D software allowed her to create visualizations of the site’s monuments based on historical and archeological data in order to show them as they might have appeared at different times in history. By pairing the 3D models made with the GIS, Sullivan was able to place her models according to their precise geographic locations within their natural landscape.

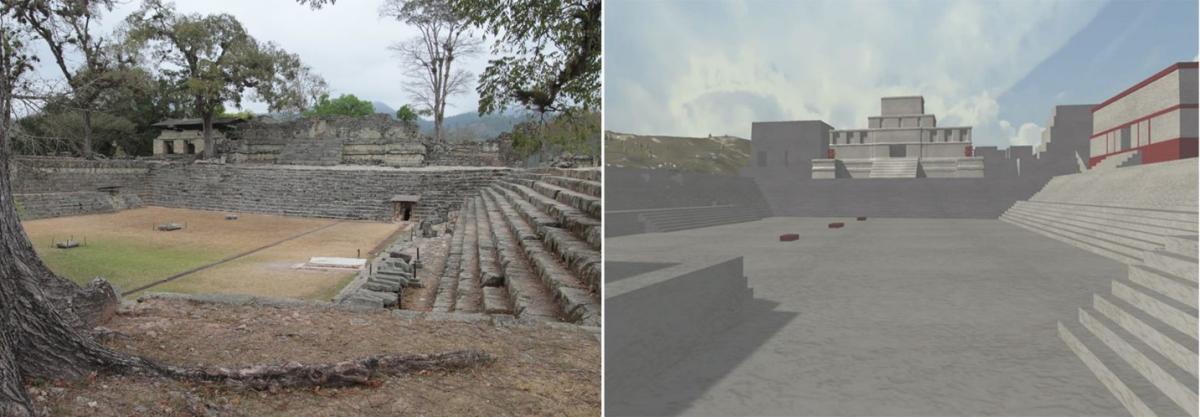

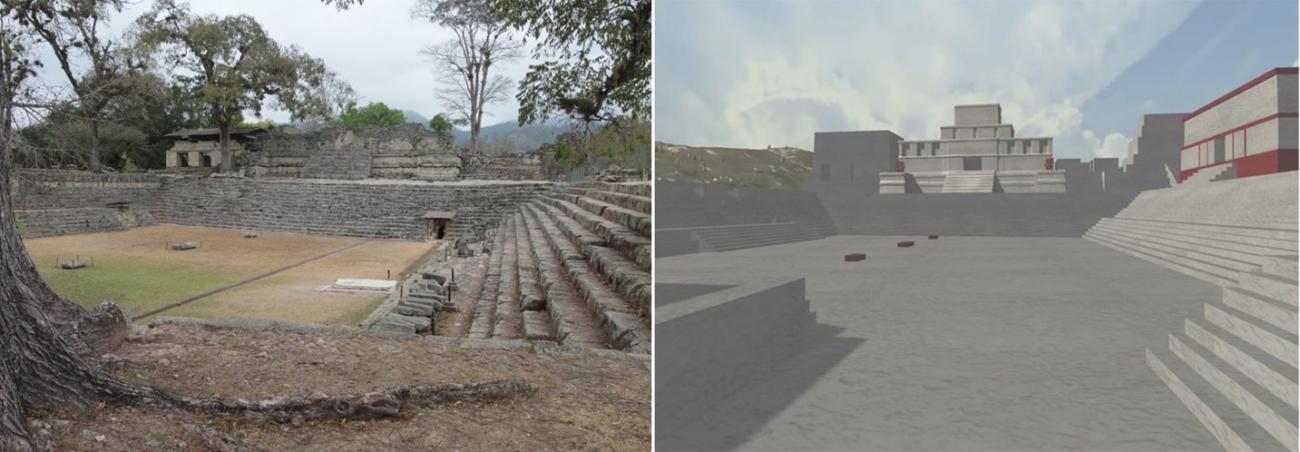

Experiencing ancient Copán

Likewise, 3D visualizations play a significant role in Heather Richards-Rissetto’s A 3D Exploration of Vision, Sound, and Movement in the Ancient Maya City of Copán (FEL-268417-20). Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Richards-Rissetto’s 3D models of Copán (Honduras) in combination with GIS, will allow her to investigate how movement, sound, and vision in the ancient city influenced the sensory experience and daily lives of inhabitants across the socio-economic spectrum.

Benefits of digital publication

More broadly, Richards-Rissetto points out that humanities scholars are shaping the methodologies and approaches associated with 3D and other digital tools in an interdisciplinary manner. “One of the challenges in studying humans and culture is that cultural studies are very complex, and resist being quantified in a binary system,” she notes. “Humanists are interested in bridging the digital with the non-digital and experimenting with the digital tools to see what works and what the digital tools can show.” For Richards-Rissetto and Sullivan, the combination of 3D and GIS modeling demonstrates how spaces that no longer exist might have been experienced by those who traversed them at different points in history.

The benefits of 3D visualizations are expanded when scholars can publish them alongside their written work on a digital platform. Besides being useful tools for individual researchers to test their hypotheses, when 3D models are published digitally with a scholar’s conclusions, they facilitate more active engagement by students, colleagues, and the public alike. Part of this is due to what Elaine Sullivan refers to as the “visual power” of the models. “We don’t necessarily have to show a single, static interpretation but, rather, with 3D we can explore and visualize multiple scenarios, while simultaneously assessing their validity and importantly allowing others to subsequently do so too,” Richards-Rissetto explains.

Transparency in digital scholarship

Beyond the visual interest and dynamism, however, digital publication allows for what Richards-Rissetto describes as a “visualization of intellectual work-flow,” which provides greater transparency of the scholarly process. To show this, the models must include access to a range of background information: meta-data, such as, the date of creation, software used, image resolution, as well as information about the structure being modeled; para-data, which includes what decisions were made in the production of the models and why; and references to relevant archival records. This is especially important in projects where past spaces are being reconstructed. Sullivan notes that although the models and visualizations she creates are based on a synthesis of historical and archeological data, they do not constitute representation of “the truth”, but rather an interpretation of the data. “If someone else were to create their own model, it would look different than mine, and that’s okay,” she explains. With digital publication methods, it is possible to include large amounts of para- and meta-data that explain how uncertainties were accounted for in the design of the 3D models, and promote transparent scholarship.

Interactive presentation of scholarship

Furthermore, digital publications allow scholars to augment the dynamism offered by 3D models with additional supporting data. The availability of these “digital assets,” according to Sapirstein, not only enables scholars to make a more compelling argument than permitted by traditional print formats, but also allows readers to engage more actively and critically with the scholarship. In print publications, Sapirstein notes that, “it is difficult to ‘back up’ any claim fully, though I do the best I can with a limited number of figures. This process still relies on a good deal of trust – trust that I have perceived the site correctly, and that I have described it accurately.” On his digital platform, however, Sapirstein can provide access to his high-resolution 3D images and digitized archival records, which, he states, is “a valuable step toward transparency, in that – short of going to the trouble of traveling to Olympia and obtaining a study permit – any interested person could review in considerable detail the features which I discuss in an analytical publication. As with the archive records, others could readily challenge

my conclusions about the temple on the basis of the digital illustrations or investigate completely different aspects of the architecture.” In a similar vein, Richards-Rissetto explains, “with 3D narratives, we can juxtapose and embed text, images, videos, sound, and even data with interactive 3D models facilitating a shift from ‘readers’ of scholarly arguments to affording greater opportunities for us to become active interrogators of scholarly research.... [We] can use 3D visualizations to actively engage readers in our intellectual workflows by linking raw or derivative data at key points in our interpretations creating greater transparency in our processes.”

Research questions lead the choice of digital methods

Richards-Rissetto emphasizes that for humanists incorporation of technology into their research is necessarily an iterative process. While she sees substantial potential in digital technologies (including 3D visualizations) across the humanities, she emphasizes that technology should follow research interests and questions, not vice-versa. She explains that her own use of technology stemmed from her research interests, “I initially delved into digital technology because my research questions on understanding social interactions in ancient Maya cities drove me to seek alternative methods. My journey using GIS for computational analysis of access and visibility led me to a need for tools and methods that also allowed me to incorporate aesthetics and ground-based perspectives (rather than bird’s eye), which turned out to be 3D technologies. I extend this philosophy into the classroom encouraging students to begin with their research interests (or questions) and NOT technology.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same

The application of digital tools to humanistic study is not without its challenges. For Sapirstein, the software for manipulating scan data is not tailored to the cultural heritage sector, and, in some cases is cost-prohibitive. “Since I have experience coding, I am finding myself devoting time to writing bespoke software for presenting the models in the way I want them. I think this is useful, in that I have created and am creating tools that can be applied generally to the analysis of 3D data of architecture, though it is also not what I would have expected to be part of an architectural historian's job. This is a common topic of discussion in Digital Humanities circles – part of our time is spent doing things that are outside the traditional limits of any given humanistic field.” Nevertheless, Sapirstein says, “on a day-to-day basis, I see that most of what we do in architectural history hasn't been fundamentally changed...I still spend most of my time reading the literature and writing scholarship about architecture.” When it comes to humanities scholarship, then, it appears the old adage is true—the more things change, the more they stay the same.