Contemporary Ukrainian literature dates its beginnings to the 1980s when Ukraine was still part of the Soviet Union, but glasnost had begun, loosening the fetters of Soviet society.

Ukrainian writers embraced new subjects. Old forms for poetry fell away and new ones, especially free verse, were adopted. The “era of festivals” commenced, and poetry performances drew large crowds in Kyiv and other cities. Such audiences may have recalled the 1960s, when the Khrushchev Thaw ushered in a brief heyday for poetry in public life as readings by Yevgeny Yevtushenko and others drew overflow crowds to football stadiums. Twenty-five to thirty years on, a particularly irreverent group in Ukraine, Bu Ba Bu, was able to get away with poking fun at the faltering Soviet regime before large audiences, further stirring the embers of Ukraine’s move toward independence, which it won by referendum in 1991. Today, poetry continues to play an important role in Ukrainian life, speaking especially to the experience of war and reflecting the independent streak for which the nation has become famous.

To gain some perspective, it’s helpful for readers in the West who may be encountering Ukrainian poetry for the first time to bear in mind a few of the basics. The Ukrainian language developed alongside Russian but remained distinct. Spoken Russian and Ukrainian are only about half mutually intelligible. In fact, modern Ukrainian is closer to Belarusian than to Russian and includes many words of Polish and German origin. The writing system in Ukraine is Cyrillic but employs its own alphabet. There are many speakers of Russian in Ukraine, especially in the east and in Crimea. Translator and book reviewer Boris Dralyuk has written that the Russian spoken in Crimea is “marinated in Yiddish and Ukrainian and sprinkled with French and Greek.”

Poet and artist Taras Shevchenko was for a long time the dominant figure in Ukrainian literature. Born in 1814, he spent time in prison for his radical ideas favoring Ukrainian independence from Tsarist Russia. His poetry painted a vast landscape and reminds the American reader of Walt Whitman. The Caucasus, an ode of about 170 lines to fighters opposing Russian aggression in 1845, is vibrant and monumental and, for having raised the common vernacular to new literary heights, retains a special place in the language of forty million Ukrainian speakers. With its celebration of Cossack folk culture and the steppes and mountains of Ukraine, The Caucasus helped articulate for Ukrainian nationalists their sense of distinction from Russia.

Following Ukraine’s independence and the Orange Revolution from 2004 to 2005, Shevchenko’s oeuvre began to fall away from its position of centrality in the nation’s cultural life. This trend has continued, following the many protests, both violent and peaceful, over suspicious election results and the assassination of a prominent journalist. By the time of the Maidan Uprising from 2013 to 2014 in Kyiv and the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas region, and now, with the new and ongoing war in eastern and southern Ukraine, poets have felt compelled to grapple with events through new language. Scholar, poet, and translator Polina Barskova sees a literary identity in Ukraine being shaped “within the realm of poetical expression.”

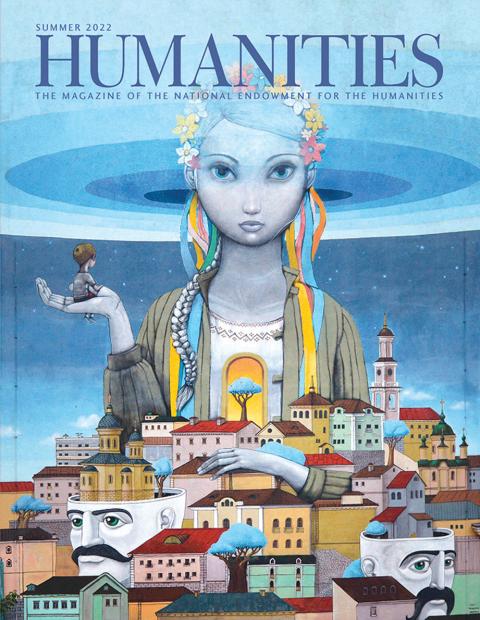

One can see what she means by looking at a handful of poets included in two NEH-funded anthologies of contemporary Ukrainian poetry and prose, both published in 2017—Words for War and The White Chalk of Days. Edited by husband-and-wife team Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky, Words for War presents 16 Ukrainian poets, writing in both Ukrainian and Russian. The inclusion of one of the Russian-language poets, Aleksandr Kabanov, has stirred some controversy in Ukraine. Maksymchuk told me in a telephone interview that Kabanov does not, however, share in Soviet nostalgia. “He tiptoes on a precarious precipice. Kabanov is a trickster and a bit of a wild card and even employs humor in his poems.” The anthology, she says, is a “polyphony of voices from different perspectives.”

In the introduction to The White Chalk of Days, editor Mark Andryczyk recounts odd facts about some of the writers that emerged during the compilation of his anthology, including this from poet Yuri Vynnychuk, who told Andryczyk that “he managed to publish his own writing in censored Soviet Ukraine by passing it off as his translations from a mysterious ancient language.” The poems of the first two poets discussed below, Viktor Neborak and Marjana Savka, appear in The White Chalk of Days, while the rest of the poems referred to come from Words for War.

In “Supper,” translated by Jars Balan, poet, translator, and literary critic Viktor Neborak, of Lviv, employs a light, modernist touch, putting a dish offered in a restaurant—varenyky, which are dumplings not unlike pierogi in Poland—out front as the central image. “There were seven of us / at one table,” we learn, “in an empty varenyky restaurant.” Some artists are at the table along with the speaker and a girl the speaker admires. It’s the late eighties or early nineties. No bombs are falling. Nothing much happens:

everyone was in his own time frame

everyone had his own window on the world

everyone had his own attitude

toward food

A few stanzas on, we’re told, “Dem ate varenyky / Henri roared with laughter / Yurko criticized the varenyky.” The speaker then, in conclusion, turns his attention, and ours, to the girl he admires:

her hair was golden

her eyes were the color of night

I would kiss her on her strawberry lips

I would have fallen for her

were it not for the cheese varenyky

With the freedom to write about anything or nothing at all, to drop the demands of social realism, and to relax the influence of the grand vision of Shevchenko, the poet is allowed to breathe. So, too, in Neborak’s surreal and lyric treatment of a bohemian night spot in Lviv—translated here by Mark Andryczyk and Yaryna Yakubyak—where, before you descend into the Nectar bar:

Green sounds echo

like a stream of blood

they flow

touch and vibrate

they’re sensed by lovers

The halcyon days, though, would soon be over.

In the ongoing hybrid war in Ukraine, soldiers in tanks and jets play traditional roles in the open, while old women report on troop movements from hiding spots they take up in forests. The writers in these circumstances—for the most part in the Donbas region—try to find the words for war. Russian-language poet Lyudmyla Khersonska has noted that Ukrainian poets need to learn again to speak their own languages. Shifts and transformations have occurred throughout the populace and within the new, sharper language that poets use to not only mourn those who have died but also to limn the losses of the survivors.

In “Books We’ve Never Read,” translated by Aksold Melnyczuk, Marjana Savka reifies this new language. In just twelve lines, the Lviv poet and publisher creates an encompassing landscape dominated by the parts of a book: “Books we’ve never read are opening for us,” the speaker states point-blank in the first line. Then, in the same stanza, she remarks, “The roads turn like pages.” This is closely followed in the second stanza by “Nothing now but the bookmark of a horizon.” In the final stanza, she observes, “The day’s reborn,” followed by “I yearn for longer books.” Each day here is, apparently, a newly made book, one that simply records the bare facts of a diurnal life. In this new place, the speaker implies, we are starting over, the stories of our lives consisting of a few brilliantly lit moments at sunrise. The final lines conclude matter-of-factly and are tinged with unnerving aplomb, “We are pure and strange as Sanskrit words. / We greet the sun whom we resemble.” The three stanzas here, quatrains, compose a twelve-liner, not quite a sonnet but ending as sonnets can, with a recognition of a new reality. Savka is, here at least, a poet still working within the lines of traditional form.

Many of the poets writing today in Ukraine, however, compose in free verse, relying more on repetition, word play, juxtaposition of images, and rhetorical devices than on traditional forms and meter to convey the harsh reality they’re witnessing. Images such as rotting fruit occur and recur. Debris lying in snow and crumbling bridges make their appearances. “Dried tree branches,” writes Kateryna Kalytko in an untitled poem, “crackle in the air like transmitters.” And from the same poem, she writes: “Words hardly fit between water and salt.”

Serhiy Zhadan, from the eastern city of Kharkiv, which, as Barskova tells us in an afterword to Words for War, was a hub of Ukrainian and Russian poetry, writes in “Stones,” translated by Valzhyna Mort, “We speak of the cities we lived in— / that went / into night like ships into the winter sea.” Zhadan’s is a journalistic poetry, which peers uncritically into the lives of individuals of the conflict, regardless of their stance, right or wrong. In Mort's translation of “Third Year into the War,” the speaker asks about the deceased at a funeral, “Which side was he fighting for?” Someone responds, “One of the sides. Who could figure them out.” Zhadan works as a civil interlocutor, has read to audiences all over Ukraine, and travels to the Donbas when he can. In “Three years now we’ve been talking about the war,” also translated by Mort, the speaker, verbally revved up, it seems, sputters:

It’s very important for us to talk about ourselves during the war.

We cannot stop talking about ourselves during the war.

It’s impossible to be quiet about ourselves.

The poem takes a step back and a deep breath and concludes: “It doesn’t influence / the number killed.”

The muse for Vasyl Makhno’s “February Elegy,” translated by Uilleam Blacker, is a nurse “who is shot through the neck / in Maidan’s winter winds.” The speaker, rather than seeking inspiration, implores, “muse, please give us some advice / and hold tight onto the forceps / for the hour of death is nigh.” The muse, though, is bruised—an angel of death, “who drags all the wounded aside.” On the streets of battle, too, stands, we learn in the final line, the bard of Ukraine himself: “I see how he keeps up the fight / ripping asunder his greatcoat— / two-hundred-year-old Shevchenko.” Makhno is a modernist, lives in New York City, and translates another modernist, Zbigniew Herbert, from Polish to Ukrainian. Even for Makhno, who returned to Ukraine to witness firsthand the Maidan Uprising, the shadow of the great nineteenth-century poet and artist has not disappeared entirely.

Lyuba Yakimchuk, born in 1985, in the town of Pervomaisk, in eastern Ukraine’s Luhansk region, is one of the most innovative poets in helping to blaze a new linguistic trail. In “Decomposition,” translated by Oksana Maksymchuk, the speaker acknowledges with seeming resignation, even with a tinge of bitterness, “nothing changes on the eastern front.” She’s “had it up to here,” she tells us, “metal gets hot / and people get cold.” Then the decomposition of the poem’s title sets in:

don’t talk to me about Luhansk

it’s long since turned into hansk

Lu had been razed to the ground

to the crimson pavement

And one stanza after, a moment of self-doubt:

yet here you are, writing poems,

ideally slick poems

high-minded gilded poems

beautiful as embroidery

Then, “there is no poetry about war / just decomposition,” a startling and damning realization, especially for a poet, who has nothing if not words. The image of sunflowers then appears, in the final stanza, not to represent Shevchenko, a saving grace in Makhno’s poem, but as further evidence of decline, even for the national symbol:

sunflowers dip their heads in the field

black and dried out, like me

I have gotten so very old

No longer Lyuba

just a -ba

Soldier-poets, too, are present and at work in Ukraine, and, as in all wars, they write their poems out of the unassailable truths that come from direct experience. As with the English-language poets of World War I, the Ukrainian soldier-poets transform that experience in profound ways. One such soldier-poet is Borys Humenyuk, who writes from a stance much closer to Wilfred Owen than to Rupert Brooke. The “high zest” for glory Owen warned against in “Dulce et Decorum Est” is replaced here, too, by the gruesome details of war seen from the trenches. “A Testament,” translated by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky, begins:

Today we are digging the earth again

This hateful Donetsk earth

This stale, petrified earth

We press ourselves into it

We hide in it

Still alive

And in one stanza on: “Tomorrow we will die / Maybe some of us / Maybe all of us.” But the speaker requests, “Don’t gather our remains from the field / Don’t try to put us back together again,” rather, “To remember us, eat the grain from the field / Where we laid down our lives.”

Aside from Aleksandr Kabanov, mentioned above, two other civilian Russian-language poets of note writing on the experience of war in Ukraine are Anastasia Afanasieva, from Kharkiv, and Lyumyla Khersonska, also mentioned above, who was born in Tiraspol, Moldova, but who now lives in Odesa. Kabanov studied journalism in Kyiv State University and employs slang and allusion in his poems to good effect. Khersonska, who translates Seamus Heaney into Russian, describes Ukraine in a poem translated by Valzhyna Mort as “a country in the shape of a puddle” and in another, translated by Katherine E. Young, echoes Stephen Crane’s refrain “war is kind,” with the speaker observing, “The whole soldier doesn’t suffer— / it’s just the legs, the arms.” Anafasieva’s position on poetry sums up what that experience must be for many of the poets writing in Ukraine today, and abroad in the Ukrainian diaspora, whether writing in Ukrainian or Russian:

Writing poetry is an attempt to penetrate into the essence of things—to name it and to speak it out. It seems to me quite obvious that the goal of poetic speech is only to name things—that is, to name them as they are, simply because no one except a poet is able to do this. Only he can reveal the essential sound.

*This article was updated on February 24, 2023, to include translators' names.