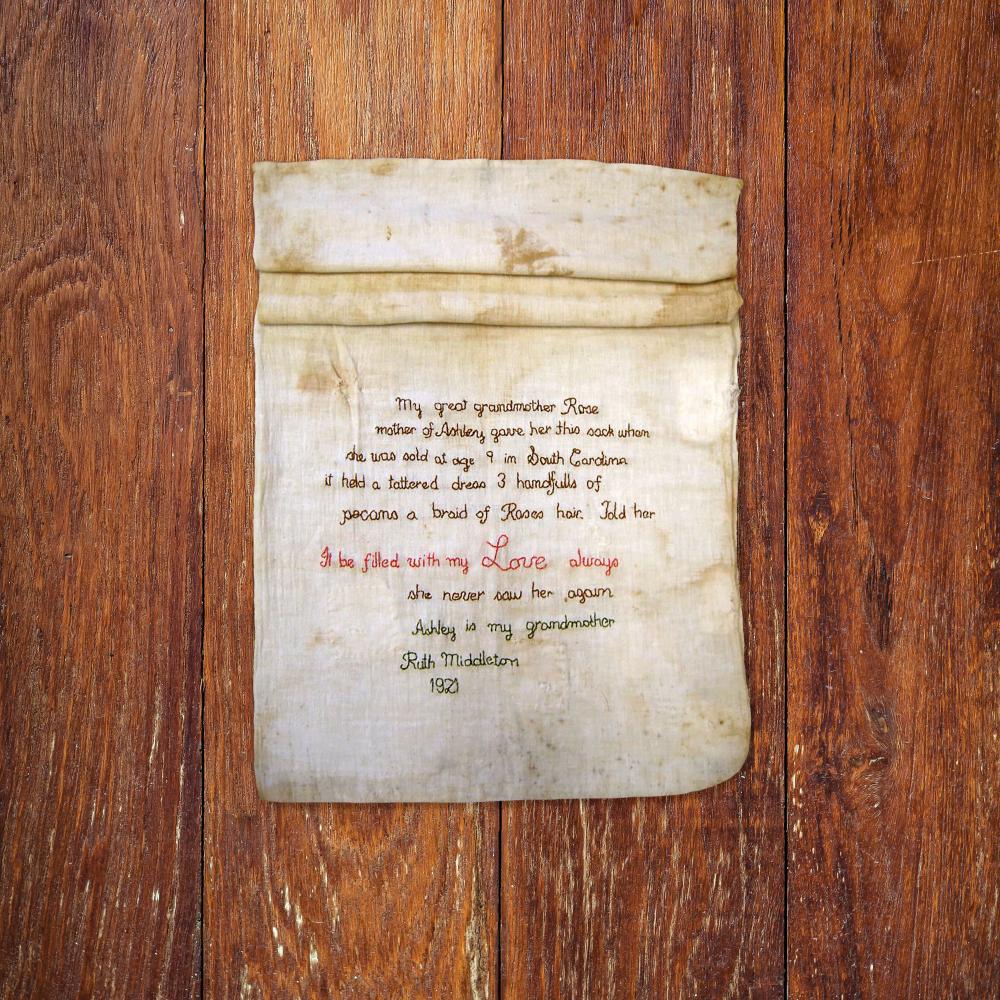

In All That She Carried, Tiya Miles tells the story of an extraordinary piece of American history, the rough cotton bag that an enslaved woman named Rose gave to her daughter Ashley in approximately 1853, as the nine-year-old girl was sold and separated from her mother forever. In this excerpt, Miles follows the thread of her own family’s history into a discussion of how quilts and other handcrafts have played a vital role in conveying the history of women, families, and nations.

My own grandmother’s voice travels across warm breezes on a hilly side street in Cincinnati, Ohio. I am nine years old, or twelve and a half, or twenty-one.

“Lord only knows what we woulda done if she hadn’t saved that cow.”

Grandmother has told this story countless times to me, her rapt audience of one, and to other women relatives in private moments over the years. Her dark eyes peer at me with the light of love behind her oversized men’s glasses, the sort that come cheapest with her Medicare plan. She does not need glamour or fanfare. The red brick porch of the Craftsman cottage is her stage. She sits on her lounger with the metal frame, its pillows changed out many times and now mismatched in shape and pattern. Her skin is the honey of bees’ combs, soft as crepe and just as creased. Her hair is a wreath of pressed cotton, once black, now white. A sleeveless, pale blue shift drapes to her calves, exposing ankles swollen from a lifetime of domestic labor in others’ homes and agricultural labor on others’ farms. She leans back and folds her hands across the broad moon of her belly, which birthed six babies in Mississippi and seven more in Ohio. In the summertime, she keeps a cool drink on the ledge of the porch wall—lemonade or sun tea sealed in a Mason jar. She reaches for the cooling liquid, wets her lips, and continues. She is my first storyteller, the one who tends me when I am sick, the one who bakes my favorite rice pudding. She is my beloved.

“If it wasn’t for my sister Margaret,” my grandmother preaches, “we woulda had nothin’ left.”

This was the defining story of my grandmother’s childhood in Mississippi. It told of a fragile family and a brave Black girl. My maternal grandmother, Alice Aliene, was born in Lee County to a mother much younger than her father. Her father, Price, was tall as an oak, with bark-dark skin. He had “eyes like an eagle’s,” to hear my grandmother tell it, which she claimed he got from a “half-Indian parent.” Price had been born into slavery’s last days. He told my grandmother, and she told me, that he had been sold away from his mother. Maybe this is why the 1870 federal census lists Price as an eight-year-old alone, with no guardian or family.

My grandmother’s mother, Ida Belle, was the yin to Price’s yang, youthful, light-skinned, with long raven hair “swinging down her back.” This mother, romanticized in the adoration of my grandmother’s words, had somehow come from means. Ida Belle had been born in St. Louis; she could read and write; she could figure with numbers. Ida Belle’s father was white and unnamed in my grandmother’s stories. Ida Belle’s mother had had no choice about this intimacy. “When those white men wanted to go with you,” my grandmother explained to me, “you went.” Ida Belle had a bit of money, a set of gold-edged plates (now in my mother’s display case), and even twenty-five acres of land in her possession. Price, Ida Belle, and their splitting-the-seams farm family of nine were getting by in rural Mississippi, the state that had harbored the worst forms of torturous, Cotton Belt slavery and would later see the gruesome murders of three civil rights workers in 1964’s Freedom Summer. They farmed 165 acres, produced between 25 and 30 bales of cotton per year, and made around $100 to $125 per bale. They had “plenty to eat” back in the 1920s, my grandmother said, and lived “comfortable” on their land. She remembered their white house with the big hallway, long porch with a double swing, “fifteen to twenty head of cows,” glossy green vegetable garden, and fruit cobblers cooling in the kitchen.

And then the family fell into debt, owing someone around fifty or sixty dollars. White men came from town, riding on horses. They appeared armed with papers that they insisted Price must sign. This was a trap. While Ida Belle could have read the contract, Price had never been educated. My grandmother inserts this detail into the story as if it might have made a difference, as if Ida Belle might have marched down to that road in a long skirt and flour-sack apron, ferreted out the secret intention, and prevented the family’s financial downfall. But I know after twenty-five years of studying Black women’s history, and my grandmother must have known from experience as she told me the story back then, that a Black woman was better off hidden than smart when white men came calling in pre-civil rights Mississippi. “I remember seeing her standing on the porch crying,” my grandmother said of her mother. Price signed the documents with his X. Weeks later, the men returned, claiming that Price had relinquished the farm. Who knows what the black marks on those papers really conveyed? The truth became irrelevant the moment those men returned with guns.

My grandmother’s words pick up speed and seem to chase each other now as she tells the story, or maybe it is my memory that blurs the details. All is panic. Who runs to hide? Who stands by as witness? Price argues with the men. Ida Belle flies to locate her young ones. The children cower. The dogs warn. The family evacuates as alarm evolves into knowing fear.

They were being evicted by the Law of the South, which is to say by white supremacist whimsy. They had little time to think or plan, to collect and pack their necessities. They grabbed at dishes, blankets, clothing but lost all of their wealth, which was the land itself, the farmhouse, and the livestock. The men took the family’s cows, which had belonged to Ida Belle. “I never will forget them, in the wagon with the horses, going on down the road,” my grandmother told me. But my grandmother’s sister Margaret, she was shrewd and she was quick. While commotion raged at the front door, Margaret slipped out the back, fetched a cow from the pasture, and led it over to the farm of Old Man Rose. He helped them, later allowing the family to rent one of his houses. My grandmother never mentioned his race.

That cow was the only thing of significant value rescued from my ancestors’ farm besides their lives. The expulsion drove my grandmother’s family into poverty. This poverty, this pressure, this unrelenting fear of loss would later push my grandmother to marry young and migrate, out of the jaws of the Jim Crow South and into the teeth of the segregated North. But the act of strength and daring shown by Margaret that day enriched them in spirit despite their woes. This is how I remember my grandmother telling it. My great-aunt Margaret, only a teen, saved the day. And my grandmother wrapped the moment up in a silk sleeve of artful story.

I never had the chance to meet this dauntless aunt. I have never even glimpsed a picture of her. But I had seen and touched and admired the work of her hands, a connection just as powerful. My grandmother kept a quilt in her bedroom that Margaret had stitched sometime after the ouster. The quilt bears an appliqué fan design: rose and mint-colored circles and ovals alternating with a regularity broken only by shifts in shade. The backing has cobalt and powder-blue polka dots on a vanilla-cream background that brings to mind the sweet smells of an ice cream parlor. Margaret had folded a blue-dot border onto the edges of the appliqué side, mixing the mild pastel fans with an altogether different feel that smacked of modernist dots and splotches. She imposed what did not fit onto her visual canvas, the mark of a creative soul as well as a rebel. This girl, whom I would never know except through stories handed down, was both a maker and a savior. She is remembered in family lore in a way that reflects regional history tinged by archetypal myth.

I inherited my great-aunt’s quilt when my grandmother passed away, more than fifteen years ago. The quilt was for my grandmother, and is for me, a treasured textile. It seems to have absorbed into its fibers the intangible essence of a past time. When I gaze at the vibrant colors of this quilt (including stains of an ancestor’s blood), I see my grandmother as a girl and imagine the faces of her kin. I feel each syllable of that many-eyed monster, Mississippi—a place where heat, terror, and love intertwined. The story of Margaret saving the cow fused with the quilt’s material. The most traumatic event of my grandmother’s childhood is embedded in it. The history of Africans in America is brutal, but we have made art out of pain, sustaining our spirits with sunbursts of beauty, teaching ourselves how to rise the next day.

I was born in the 1970s, a chaotic time to be sure, but more hopeful by bounds than the 1920s, when my grandmother and her sisters were young. I never knew enslavement firsthand, never experienced legal segregation, yet I savor the story of Margaret, her cow, and her quilt now more than ever. This fabric and the tale I associate with it have blanketed and anchored me, a reminder of dignity preserved, and of the hope in our dire times that something necessary for the preservation and elevation of life might, in the end, be saved.

There are myriad lessons in the story of the cow. What strikes me upon this telling, as I also ponder Ashley’s sack, is the emphasis on girls and women, acts of rescue, and the salvaging of vital things that hold the deep meanings of our lives. This family story is about the resourcefulness of women and girls, even the most marginalized and maligned of them. It illustrates how the overburdened of the world can persist through unanticipated hardship. And this story suggests how instructive memories of perseverance from the past can be, especially when fastened to things that serve as aids of recall and connection.

I link the eviction to the quilt because of the heroine they have in common. In the case of Ashley’s sack, the attachment is even more material. That story from the past is sewn directly onto the fabric. As the oft-quoted scholar of U.S. women’s history Laurel Thatcher Ulrich recounts in her book The Age of Homespun, folks in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries sometimes affixed stories to objects, tucking fragments of paper about origins or events from the times into woven baskets, or pinning information about an object’s owner onto the heels of woolen stockings, or even painting wordy descriptions onto wooden chests of drawers. This impulse to preserve past knowledge by hitching narrative explanation to items exhibits what Ulrich calls the “mnemonic power of goods.” Things become bearers of memory and information, especially when enhanced by stories that expand their capacity to carry meaning. And if those things are textiles, stories about women’s lives seem to adhere with special tenacity, even as fabrics, because of their vulnerability to deterioration and frequent lack of attribution to a maker, have been among the last kinds of materials that historians look to in order to understand what has occurred, how, and why.

My attachment to an ancestral quilt tethers me to the breathtaking weight of the African-American past. Certainly, my own history is partly what drew me toward the sack, inspiring a wish to know the women behind the object and explore more deeply traditions of African-American craft and family bequeathal. This is a feeling I’m sure to share with other women (and men) of Black, southern, rural, or crafting heritages. Many of us have felt in our lives the allure of the cloth as a twining cord connecting us to history. Some save and repair hand-me-down table linens. Others hunt the flea market aisles for vintage fabrics. A few of us learn the skills of traditional sewing and quilting to reproduce the experience and art of our foremothers. The past seems to reach out to us through these fabrics and the practices of making them that have survived over time. Gathered up like crisp ends of a cotton sheet fresh from the washing, past and present seem to meet above the fold. We feel a sense of contact with the women who preceded us. We wonder if gaining knowledge about their lives can shine new perspective on our own. And as we discover the lives of these women from a time so different from ours, we enhance our ability to peer across other differences—of race and culture, class and status, ability and disability, youth and age. In this intermediate space where the fold of the fabric forms, we glimpse not only our foremothers’ lives but also our foremothers’ allies and adversaries. We begin to see the makeup of all their intersecting worlds and appreciate a larger swath of interwoven experience. We notice a shift from the self to the other, from personal and family history to local, national, and even global history. This dawning awareness leads us to trace all of the intertwined threads, to appreciate that there is one earth and one humankind, one social fabric of many folds in dire need of mending.

It may not be coincidence that we feel this expansion of self in the quaint attic rooms or antiques shops where we ponder the fibers that remain. An essential medium of social messaging, fabric announced information (often about social status), triggered memory (of events and people), and even bestowed protective magic (through embedded sacred material and shared belief). Before word processors, the printing press, and wood-pulp paper, cloth fashioned by women makers preserved the “mythohistories” of entire groups. Noblewomen spun thread on gold and silver spindles, fashioning tapestries with grand visual narration. In ancient Greece, Europe, and the Mediterranean, cloth did the work of retaining stories of distant kin, as women “recorded the deeds and/or myths of their clans in their weaving.” These tapestries, laden with messages of historical events and mythological symbolism, bore a critical record-keeping and cultural function as “story cloths.” While few ancient women had the luxury of twining their thread on golden spindles, the tradition of the story cloth of yore continues in the pieced quilts and cotton windowpane coverlets, embroidery samplers and crocheted afghans that we hand down through families with stories attached. Though early women’s history can be elusive, women need not “conjure a history for ourselves,” says the archaeologist Elizabeth Wayland Barber. We do not have to magically pull our collective past out of thin air. “Very little of the ancient literary record was devoted to women,” Barber continues. “Here among the textiles, on the other hand, we can find some of the hard evidence we need.” Similarly, in her essay “African-American Women’s Quilting,” the historian Elsa Barkley Brown insists that if we “follow the cultural guides which African-American women have left us,” we will “understand their world.” Barber, a specialist in the ancient past, and Brown, a scholar of the recent past, agree on this: Our foremothers wove spiritual beliefs, cultural values, and historical knowledge into their flax, woolen, silk, and cotton webs. The work of their hands can lead us back to their histories and serve as guide rails as we grope through the difficult past. Here I attempt, alongside you, an unpredictable expedition into the lives of Black women during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow segregation, locating them in the contexts of their dynamic social worlds by tracing the threads of a story cloth. I seek to uncover the story of an enigmatic object and its makers; to explore the historical meanings of things in Black women’s lives, Black lives, and women’s lives; and to stitch into our cultural memory the chief values Rose upheld: love, hope, and salvation.

Excerpted from All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake by Tiya Miles. Copyright © 2021 by Tiya Miles. Excerpted by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.