The Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 inaugurated a new era in the history of Europe. Led by the Arab general Tariq, Berber military forces from Morocco quickly swept through the Iberian Peninsula, extinguished the Visigoth Christian Kingdom, and inaugurated nearly 800 years of Muslim rule in Spain. Henceforth, the territory of medieval Spain held by the Muslims would be known as al-Andalus (Arabic) or Andalusia: The Jews applied the Hebrew name Sefarad to it. Andalusia endured on an ever-diminishing scale until the last Muslim outpost, the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, fell in 1492.

Andalusia or medieval Muslim Spain was located at the westernmost frontier of the Muslim and Christian worlds. Its boundaries were never static and the relations among its multiethnic inhabitants were rarely peaceful. Like all frontiers, Spain’s was suffused with a militant ethos and characterized by frequent friction. Various Arab tribal groups engaged in continuous warfare and the country was riddled with rivalries between Arab and Berber peoples, and torn by conflicts of each among themselves. The Christian population was animated by a fervor to reconquer the Peninsula from the Muslims (a movement known as the Reconquista). Yet, paradoxically, medieval Spain also holds the distinction of being the sole place in Europe where Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived side by side on the same soil, frequently in harmony. This unique commingling has given rise to a good deal of romance and theorizing among modern scholars about medieval coexistence, or convivencia. At times tolerant, at other times intensely intolerant, Spain’s intergroup relations formed a fragile coexistence of Muslims, Christians, and Jews. Although often tenuous, the coexistence of diverse languages, peoples, and religions produced an extraordinary symbiosis and distinctive civilization manifested in art, architecture, music, science, and literature. This medieval pluralism was particularly well suited to the expression of Jewish culture.

Following the Arab conquests, successive waves of Berber and Arab tribes, Jewish refugees, and Mediterranean merchants migrated across the Strait of Gibraltar from North Africa and the Middle East onto the Iberian Peninsula. They were attracted by the country’s reputation as a land of opportunity and rich potential.

Yet Muslim rule was unstable for many generations, and military campaigns constantly prevailed. Muslim attempts to push northward into France were thwarted in the 730s, and the northernmost provinces of Iberia (Asturias and Leon) remained in Christian hands to serve as a rallying point in a centuries-long movement of reconquest of the entire Iberian Peninsula for Christendom. Despite the constant military confrontations between the two religious blocks, inventions, luxury goods, artistic motifs, and ancient and contemporary ideas, as well as tradesmen and clerics moved back and forth across the porous and ever-shifting borders. In like manner, the legacy of antiquity and the Middle East was transmitted via medieval Spain to the rest of Europe. The Jews of Spain, being multilingual, urban, and literate, filled an economic niche in the predominantly agricultural economy and also played an important role in the circulation of goods and ideas from the Arabic- to the Latin-speaking world by way of Hebrew and the Iberian vernaculars. At the same time, they often found themselves caught in the middle between the two faiths and periodically suffered as victim of both.

Andalusia held a special place in the dar el-Islam (House of Islam) as the sole Muslim outpost on European soil (with the brief exception of Sicily). Although Andalusia was linked to both the Christian and Muslim worlds, it was not fully part of either. It served more often as a borderland or battleground than as a meeting ground of the two competing civilizations. Economically, the Iberian Peninsula was a transit zone between Christian Europe and North Africa and the Near East. An anomaly in Europe, Spanish society defined itself in relation to the coexistence of the two rival civilizations.

Most of the Jews of Spain lived predominantly under Muslim rule from 711 until the late eleventh century, when the Almoravid dynasty began to implement anti-Jewish legislation. With the invasion of the Almohads from North Africa and their imposition of Islam on Jews and Christians in 1147, the Jews fled to Christian Spain. They remained under Christian rule in an increasingly precarious position as the Middle Ages progressed until their expulsion in 1492. Over the centuries, the Jews often found themselves in the middle of the two powers, serving as mediator and translator between the two, fleeing from one realm to the other when necessary. These historical and cultural factors assured that Sephardic Jews would develop as a unique branch of the Jewish people—multilingual, multitalented, and also deeply attached to a place where they lived for over a thousand years. In addition, Sephardic Jews reveled in the cultural stimulation of the Iberian civilization and were inspired by it to craft unique forms of self-expression. The medieval Hebrew poetic revolution, Sephardic explorations of philosophy and science, and their creation of monumental legal codes were all products of the co-existence of the three cultures in one territory.

In 756 the last surviving member of the Umayyad dynasty in Damascus, ‘Abd ar-Rahman I (756–788) fled the carnage of a coup d’état and escaped to Spain, establishing the house of the Umayyads in Córdoba. He proceeded to establish a kingdom that would revive the splendor of Umayyad Damascus and rival the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad in opulence and power. ‘Abd ar-Rahman I and his successors Hisham I (788–796), al-Hakam I (796–822), and ‘Abd al-Rahman II (822–852) imported hydraulic experts, artists, and expert administrators, and set out to repair the old Roman routes and aqueducts. They endowed libraries and mosques, including the monumental mosque of Córdoba. Their determination to replicate the lost glory of the Umayyad Caliphate in Syria led to the importation of trendsetters from Baghdad and the establishment of a dazzling court in the environs of Córdoba. In 929, ‘Abd ar-Rahman III (929–961) declared a Caliphate in Córdoba and set Andalusia on its independent political path. Conversions to Islam multiplied and economic life quickened as talents, goods, and merchants flocked to the country from North Africa and even from parts of Byzantium. Travelers marveled at the variety and wealth of goods that overflowed in its markets and the elevated standard of living of its towns. Commodities from the entire Mediterranean moved relatively freely on land and sea. In the hyperbolic recollections of Arabic chroniclers, the Umayyad kingdom was nostalgically recalled as a kind of El Dorado, or Promised Land, or as a tenth-century visiting German nun declared, “the Ornament of the World.”

Spain’s multireligious and multiethnic human landscape represented an anomaly in medieval Europe. Many modern scholars have disagreed about the precise nature of medieval Spain’s human mosaic, erroneously comparing it with modern forms of tolerance and multiculturalism. In fact, Spain was scarcely a site of tolerance paradigmatic for modern pluralistic societies. Medieval Muslim, as well as Christian Spain, begrudgingly tolerated multiple religions. Even at its most hospitable moments, medieval Spain was a land of inequality. Jews or Christians were tolerated in Muslim Spain as autonomous religious groups, but it was the toleration by the superior of the inferior, by the overlord of the underling.

Under Islam, the Jews were defined as a so-called “protected people,” dhimmis, who received “protection” in exchange for submission to an elaborate set of humiliating political and social restrictions and the payment of discriminatory taxes. In the Andalusian hierarchy of peoples and religions, the Arabs were highest in the social pyramid and Berber Muslims were second on the social scale. Converts to Islam of other ethnicities were deemed inferior. Christians were still lower down and slaves and Jews were at the bottom of the social order. From the early years of Islamic civilization, Muslim jurists, basing on Qur’anic directives, devised an elaborate hierarchy in which monotheistic non-Muslims, such as Christians and Jews, would be “protected” at a low level and tolerated as second-class citizens. Guidelines for their treatment were embodied in the “Pact of ‘Umar.” Limitations on the status of non-Muslims included discriminatory clothing regulations and occupational restrictions. Non-Muslims were required to pay a poll tax (jizya) as well as discriminatory taxes on agricultural produce.

For the Jews, previously subjected to discrimination and persecution under Visigothic rule, the limitations that the Muslims imposed appeared relatively benign. In return for their subservience, Jews were guaranteed the free practice of their religion, the administration of their own affairs, mobility, and the freedom to engage in a variety of occupations, provided they didn’t exercise authority over a Muslim. Given these basic assurances, Jews in Muslim Spain found themselves in a rapidly expanding self-confident and stimulating civilization. Social discrimination did not preclude cultural sharing. The distinction and tensions between the two spheres—the cultural and the political—was often expressed eloquently in the poetry of the Jews of Spain. The very asymmetry between cultural sharing and social and religious ostracism was itself a creative factor in shaping Sephardic Jewry.

Over the centuries Andalusia and its capital, Córdoba, has become synonymous with the emergence of “Sepharad” as a definable entity in Jewish history. It is closely associated with the beginnings of revolutionary experimentation in new forms of Jewish self-expression and the appearance of a new Jewish personality, one at home equally in Torah and secular culture. Most of Sephardic Jewry’s daring innovations in the manipulation of the Hebrew language in versification or Sephardic interest in philosophy and science flourished while the Caliphate of Córdoba briefly blossomed (929–1031). With the breakup of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the eleventh century, Andalusia was divided into more than two dozen statelets or mini-kingdoms (the Taifa kingdoms 1031–1089), each boasting its own court of poets and scientists and a patronage system that included the talents of the minority populations. Jewish courtiers flourished in Saragossa, Granada, Mérida and elsewhere, sponsoring their own secular salons that mirrored the dominant hybrid culture. Jews branched into astronomy, cartography, medicine and mathematics, philosophy and Hebrew and Arabic philology, and poetry.

For a brief period of time, a veritable Golden Age of Jewish culture occurred. Rabbi, court physician, poet, and philosopher Yehudah Halevy’s career straddled the era of Christian reconquest in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Considered the bard of medieval Jewry, Halevy’s poetry continues to adorn Jewish liturgy, while his philosophic defense of Judaism and the Jewish people provided a popular apologetic text for beleaguered Jewish communities everywhere, even into early modern times. Another influential figure was Moses Maimonides, who harnessed Aristotelian thought to rabbinic Judaism, also providing Jews with a monumental code of law that remains a model of lucidity. Although his greatest works were composed in exile in Egypt, Maimonides remains the towering thinker of medieval Jewry and a foremost example of Sephardic mastery of Judaic and classical traditions. And the work of the Cresques family of Majorca and Abraham Zacut provided fundamental scientific and cartographic advances that changed the geographic horizons of early modern Europe.

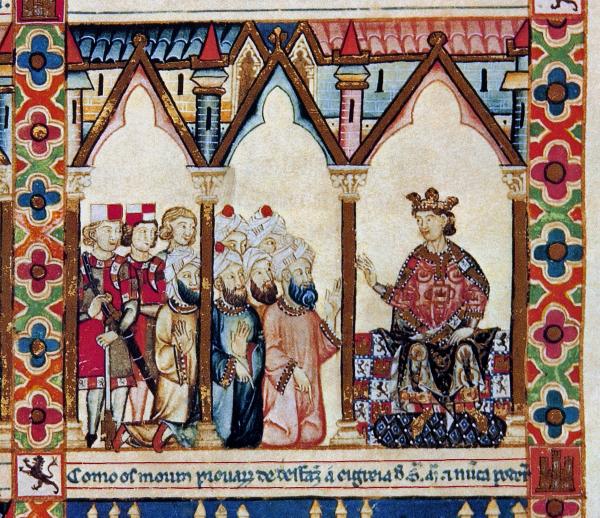

With the Almohad invasion of Spain in 1147, the Jews were forced to either accept Islam or to flee, and Jewish life in Muslim Spain virtually ceased as Andalusian Jewry scattered to North Africa, Provence, and Christian Spain. The rich culture they had developed in Andalusia persisted for a while on the soil of Christian Spain, as did the impact of their courtier class on Jewish society. Between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, most of the Peninsula fell to Christian rule. Iberian pluralism gave way to religious fanaticism as Spain increasingly embraced the antisemitism of medieval Europe, including its false accusations of host desecrations, blood libels, forced religious conversions, and pogroms. Despite the mounting attacks, Sephardic Jews continued to serve as cultural intermediaries, economic pioneers, and skilled artisans. They figured prominently in the famed translation circles at the court of King Alfonso X, known as Alphonso the Wise, where they formed an integral part of the interfaith teams that translated the classics of antiquity and the Muslim world into Latin and the vernacular and thereby transmitted their wisdom to the West. Jews also participated in Alphonso’s crafting of the Castilian language.

In 1478 a national Inquisition was established in Spain, designed, in part, to ferret out those forced converts who were secretly practicing Judaism, an act that was considered tantamount to heresy. When Granada fell in January 1492, the dream of the Spanish monarchs to unite the peninsula in one Christian community was almost realized. In March 1492, inspired and guided by their Inquisitorial confessors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella decreed the expulsion of the Jews. On August 2, the Jews of Spain were either converted to Christianity or forced into exile. The Muslims of Spain were forcibly converted to Christianity a few years later and ultimately expelled in the seventeenth century. Albeit broken in spirit by their tragic fate, the scattered Jewish exiles were armed with a sense of pride in their illustrious ancestry and legacy of creativity. Spain’s legacy of medieval pluralism is remembered in some of its architectural monuments and in the special Spanish language of the Sephardic Jews (known as Ladino). Although the majority of the bearers of Ladino were murdered in the Holocaust, the fruits of the medieval encounter created by Moses Maimonides, Solomon ibn Gabirol, Samuel ibn Nagrela, and Moses ibn Ezra—to name only a few of the hundreds of Sephardic luminaries—are today integrated in the legal, mystical, and liturgical traditions of Jewish culture.