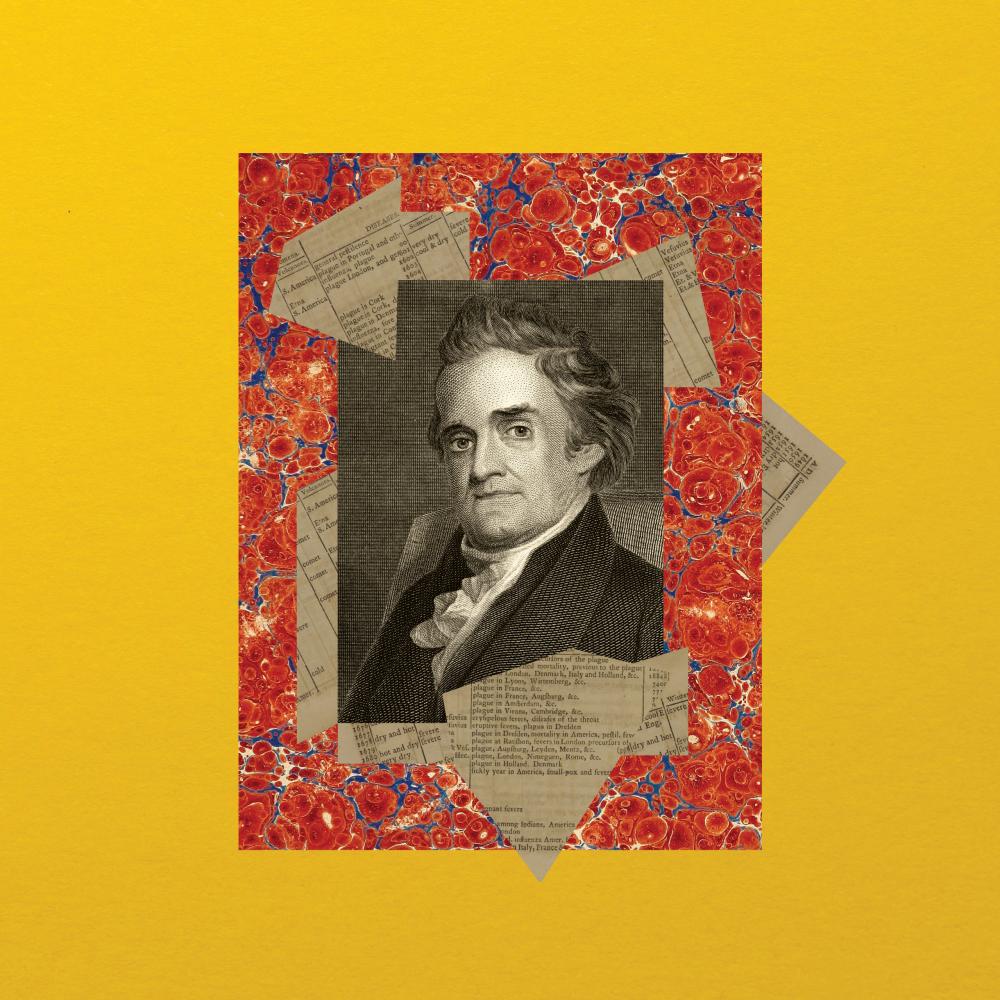

Noah Webster was an all-around do-gooder of the founding generation. He is remembered specifically for his blue-backed speller and the leading role he played in the creation of an American dictionary. In the speller, first published in 1783, he supplied a much-needed textbook. With it and other schoolbooks, Webster helped spread the founding mythos of the republic. In his 1828 dictionary, he built a monument to American authors and usage. But, in the course of a busy remarkable life, Webster made numerous other contributions as well.

Webster pioneered the lecture circuit and offered singing lessons for a fee. As a writer and a political thinker, he was known to many of the great names of his time. He visited Mount Vernon to see George Washington, who passed along the young man’s pamphlet, Sketches of American Policy, to James Madison, who read it with interest. Webster was friendly with Ben Franklin—the two men both dreamed of bold new spelling reforms.

In Hartford, Connecticut, Webster, a husband and a father, was a citizen of the first rung. A descendant of early settlers, he became a booster for many schemes of public improvement, from the introduction of currency to replace bartering to the founding of a charity to support widows and orphans. He opposed slavery, consistently and publicly, on moral and philosophical grounds but believed the most persuasive thing to say against it was that slave labor was less productive than paid labor.

One crude measure of Webster’s stature is how much, in certain quarters, he was disliked. In 1795, he used his pen to defend Chief Justice Jay’s commercial treaty with Great Britain, and faced a storm of abuse. Already well known for his work on spellers and grammar, Webster was at the time the editor of a federalist newspaper in New York City called the American Minerva. The paper was relatively successful for a while, particularly in its political gamesmanship: aiding the federalists while distressing the Jeffersonians.

Webster’s enemies took revenge in their own newspapers, calling the stiff-postured patriot a fool, “a most learned Stultus,” a “pusillanimous, half-begotten, self-dubbed patriot,” a “scribble of British faction, this ephemeron of literature, this petite maitre of politics.” Webster was called a “demagogue coxcomb” and many other fancy insults one might decode with the help of a dictionary.

Even at his most public spirited, Webster, hungry for applause, drew brickbats instead. That same year, he issued a circular letter inviting American physicians to weigh in on the causes of yellow fever, promising he would publish a volume, at his own expense, collecting their comments to make known all the available facts about this terrible scourge.

From the usual tomato-throwers came a great volley of abuse. Benjamin Franklin Bache, in his newspaper Aurora, published his own open letter, claiming to be from “A Fellow of the College of Physicians.” Addressed sarcastically to “Noah Webster, Esq., Author and Physician General of the United States,” it read in part:

When men of your eminence condescend to turn bookmakers for Physicians; when a man in whom all the rare qualities of human nature centre; when a man who can recite the etymology of words with as much facility as a child can recite its alphabet, deigns to step forward in behalf of the faculty, it would be the extreme of rudeness and brutality not to lend an attentive ear to him, and furnish him a ladder to mount to fame and guineas.

Yellow fever had claimed the lives of more than 4,000 people in Philadelphia and in the years following mounted impressive death tolls in several other cities from Boston to Charleston. It had been seen before but only rarely, and there was no consensus on where the disease came from or how it spread.

Wrote Webster:

In August 1793 commenced in Philadelphia that dreadful pestilence which alarmed the United States, and spread terror and dismay over that city. The spring diseases, which ushered in this malady, were influenza, scarlatina and mild bilious remittents. . . .

During this epidemic, the weather was very sultry and dry. About the 12th of September, fell a meteor between the city and the hospital. The number of victims to this disease was 4040.

A controversy arose among the physicians in Philadelphia, relative to the origin of the plague, one party tracing the disease, as they supposed, to infected vessels from the West-Indies; the other ascribing it to exhalations from damaged coffee and filthy streets. The controversy has occasioned an unhappy schism among the medical gentlemen, and the citizens of Philadelphia.

His critics were right that Webster was not shy about asserting himself in the public square, but a fairer way of stating the matter is that he had a gift for spotting opportunities to serve his country while promoting his own interests. The medical establishment’s failure to agree on the causes and treatment of yellow fever was, indeed, such an opportunity.

“Gentlemen,” he wrote, “As a malignant fever has, for three summers past, raged in different parts of the United States, and proved fatal to great numbers of our fellow citizens, and extremely prejudicial to the Commerce of the Country, it becomes highly important to take such efficacious steps as human wisdom can devise to prevent the introduction, arrest the progress, or mitigate the severity of such a serious calamity.”

“The world’s first scientific survey,” according to Webster biographer Joshua Kendall, Webster’s circular letter called on physicians to write to him what they had learned while treating yellow fever. He knew in advance that his correspondents would disagree with each other, but a final cause could not be assigned to yellow fever without hearing all the evidence. Rather like today’s news articles soliciting and comparing the opinions of medical doctors or epidemiologists, Webster’s inquiry was meant to discover a range of expert opinion.

His critics were slowing him down, though. When the Argus, a Jeffersonian newspaper, delayed in printing Webster’s call for testimony, Webster complained to the editor in a manner that says much about his character while exemplifying the high tone of public language in the late eighteenth century.

“Humanity,” he wrote, “is a common cause and one that should level all distinctions of party. The investigation of the causes of disease and the means of alleviating the calamities of life is the business of every good citizen, whatever be his profession. . . . And no man whose heart is not hardened by party prejudices can wish to throw cold water on the undertaking.”

The medical establishment responded favorably to Webster’s proposal. His work was encouraged by Benjamin Rush, the signer of the Declaration of Independence who was a major figure among Philadelphia’s doctors, and was supported by several physicians, who wrote at length to describe what they had seen. These diligent observers working before the development of the microscope come across in the resulting volume as nothing less than passionate doctor-detectives. They studied their patients with the utmost care and searched high and low for what ailed them. Whether right or wrong in their conclusions, however, in speaking publicly, they were risking censure.

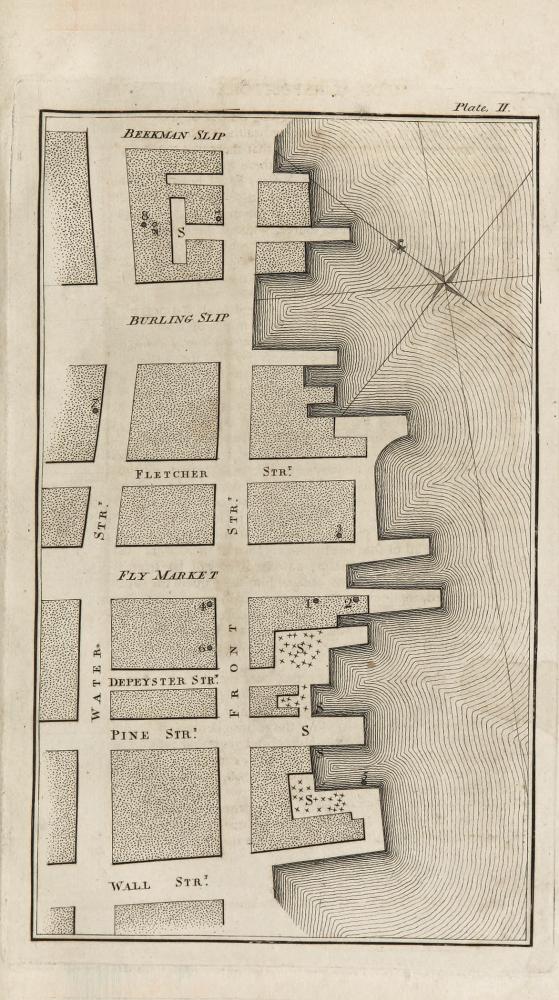

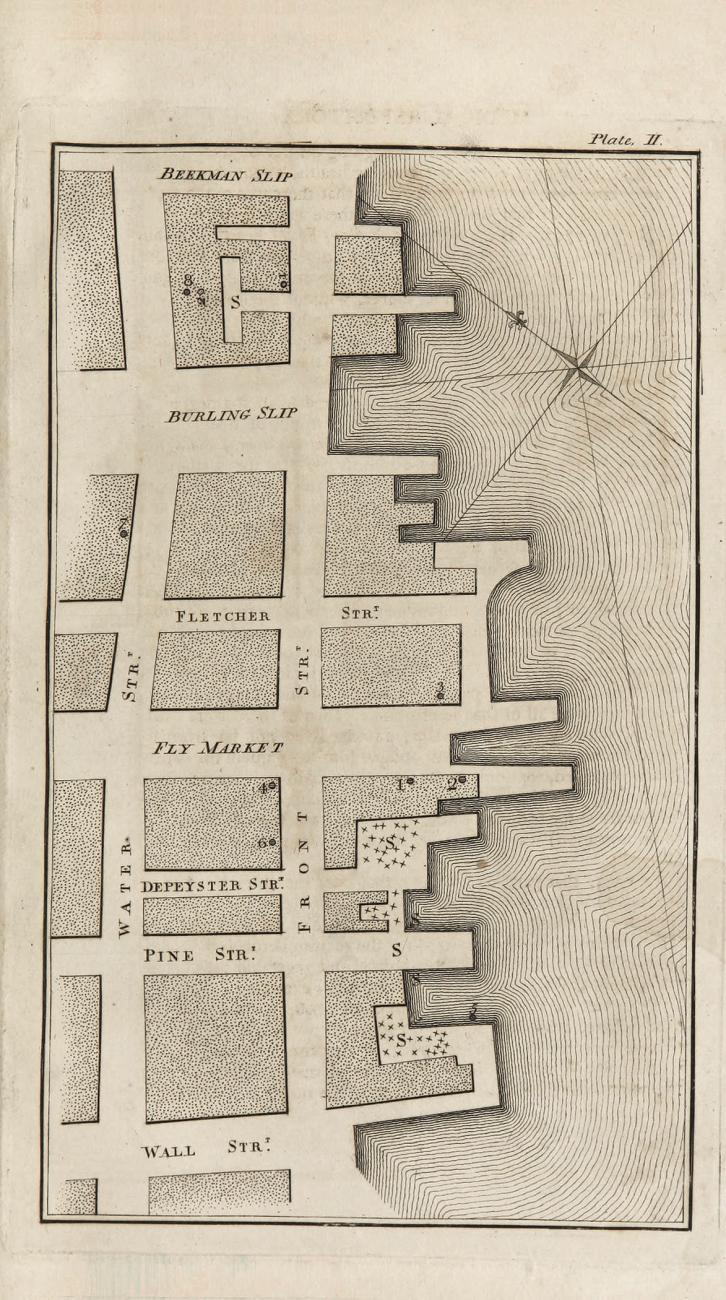

Valentine Seaman, a physician on the health committee of New York, reported from the center of the epidemic that hit Manhattan in 1795. “I am well aware of the loss of reputation that I may sustain, from attempting . . . to support opinions which are very unpopular with the inhabitants of this city,” he wrote.

Seaman’s report begins with a discussion of the great summer heat—it being universally understood that the threat of yellow fever disappeared in the fall with the arrival of cold weather. Then, very quickly, he mentions several factors that scientific history will later show are critical to the spread of yellow fever.

“Musquetoes,” he writes, “were never before known, by the oldest inhabitants, to have been so numerous as at this season, especially in the south-eastern part of the city,” which he calls “the grand center of the calamity.”

Thinking geographically, Seaman identifies certain neighborhoods and even blocks, usually low-lying and near water, that are particularly rife with the disease. “It raged with peculiar violence in the vicinity of a most intolerable pent up sink, to the west of Peck-slip, which is the receptacle of all the refuse kitchen articles, and yard wash of a number of lots fronting Pearl and Water-streets.”

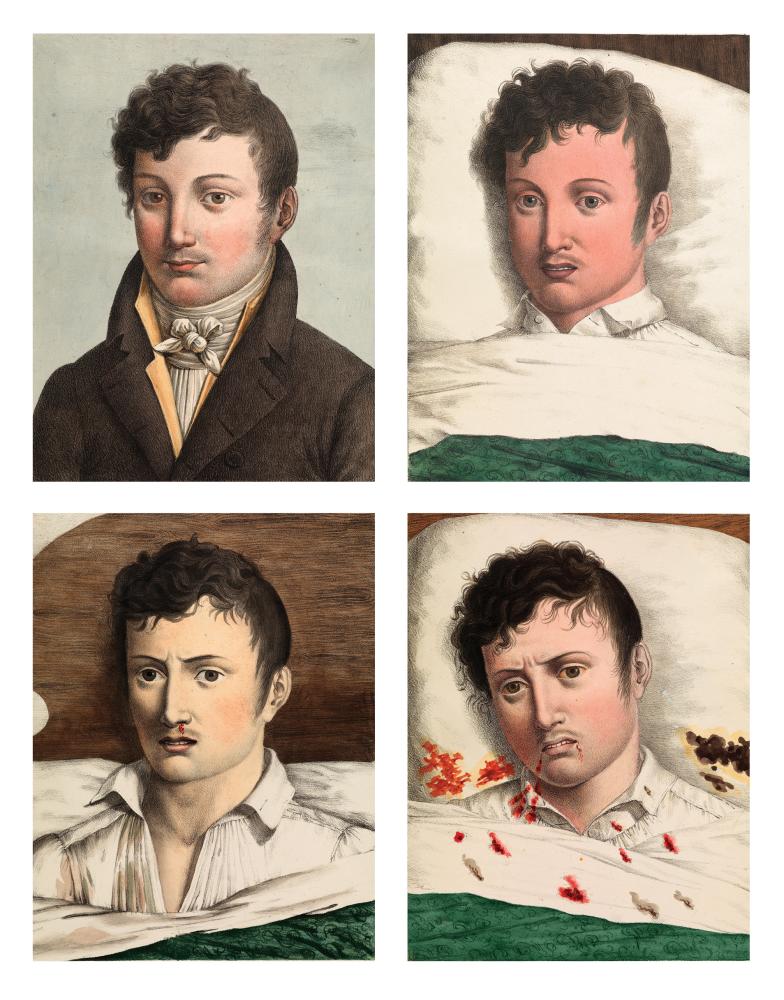

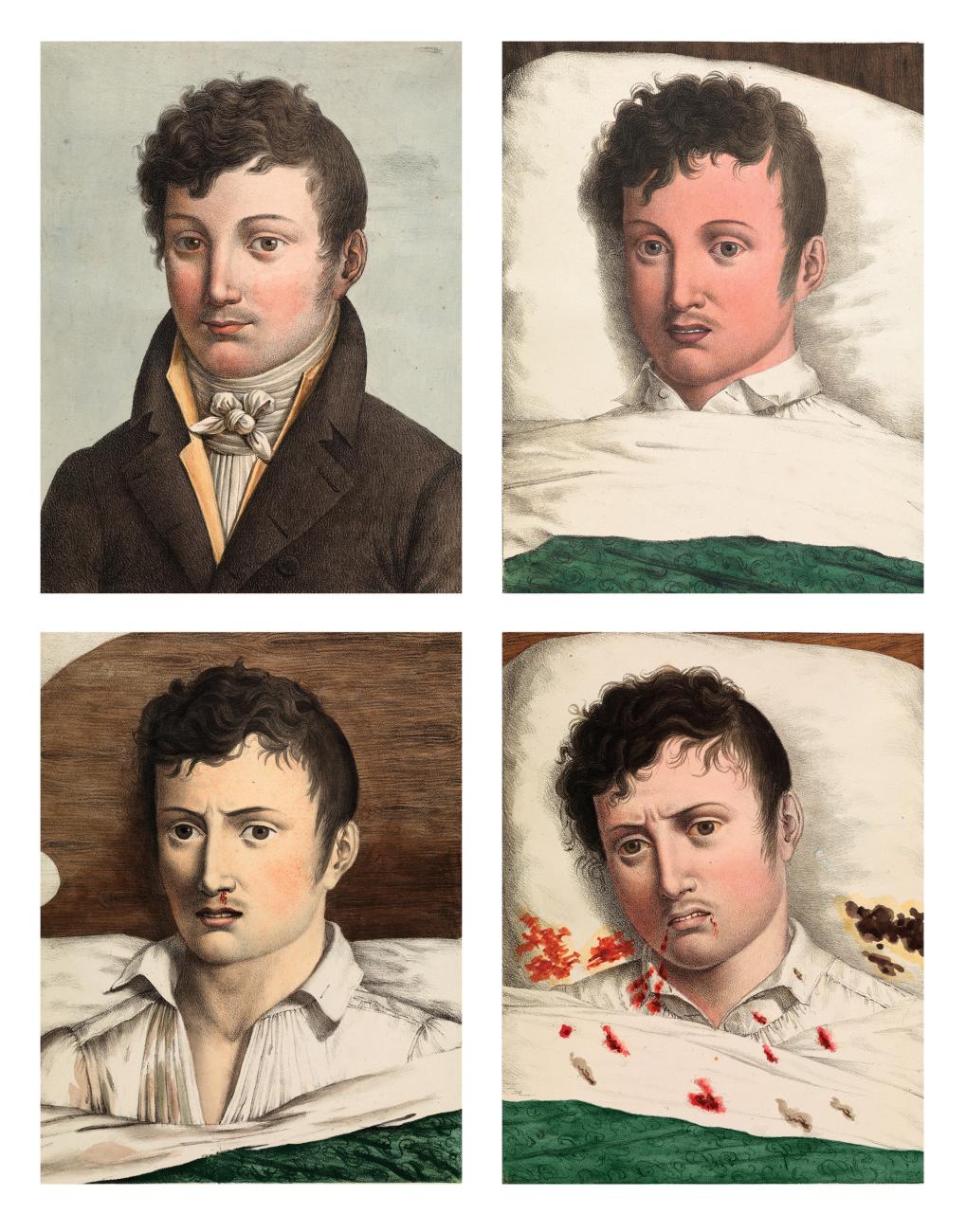

He runs down the symptoms of yellow fever, beginning with fatigue, followed by nausea and vomiting: “a puking of fluid exactly resembling coffee.” As the victim’s jaundice shows in “a yellow tinge” on the skin, “Musquetoe bites, which before had entirely disappeared, shewed themselves . . . in small purpleish red spots.”

One of the bitterest controversies surrounding yellow fever centered on whether it could be transmitted from one person to another. Another, related, controversy concerned the role of air in spreading the disease. Like many others, Webster himself believed firmly that something in the air facilitated, if not caused, disease, leading him down some very wild paths of speculation.

Those doctors whose reasoning stayed closest to empirical and observable fact were much closer to the truth about whether yellow fever could be transmitted from person to person. Seaman noted that during the outbreak in Philadelphia several people with yellow fever came to New York City, became sick, and died without infecting anyone. And though he had followed up on various reports to the contrary, Seaman knew of not even one authenticated case of a nurse or an attendant who had not been to the city themselves who had caught the disease.

Bleeding was commonly prescribed for yellow fever, along with curatives such as bark and various other medicinals that sound today like home remedies: rhubarb, wet cloths, broth. Even spirits and tobacco smoke were among the recommended treatments. Mercury was another common prescription, as was laudanum to relieve pain and suppress the cough. Emetics of one type or another were popular with physicians who believed the secret to yellow fever, which attacks the liver and kidneys, lay in the stomach and bowels.

More impressive were the policies and public works physicians recommended. Seaman’s suggestions ran from elevating streets in low-lying areas, to cleaning and paving streets and improving the sewer system.

Frequently, the physicians complained of filthy city streets, garbage that lingers, cellars that flood. During the summer of 1795, said Dr. E. H. Smith, the weather was so hot and wet, that “every article of household furniture, or in use about a house, susceptible of mould, was speedily and deeply covered in it.”

The smell of late eighteenth-century life seems even further removed from the present than the state of its medical knowledge. Docks and wharves are singled out, especially as the tide recedes and “vegetable, animal, and excrementitious matters, being thrown in, at all times, instead of being cast into the stream, ferment, putrify, and render the stench truly pestiforous.”

Better air, more ventilation, and the opening of windows are recommended for the sick and those looking to stay healthy. Personal habits receive as much attention as any medical intervention. Exercise and sobriety are recommended in practically all of the letters in Webster’s volume. Too much wine, too much sun, and too much high-living are officially discouraged.

One notices also a striking emphasis on eating vegetables and the dangers of too much meat. “An animal diet,” said Smith, “or a great use of animal food, especially in summer, and when there is a general disposition to fevers, is thought by many physicians, of our own and other countries, to favor their production; and a vegetable diet, on the contrary, to be a preventative, or preservative, against them.”

If a large part of late eighteenth-century medical thinking was modest in its claims and sometimes wise in its recommendations, a good chunk of it, especially in the discussion of yellow fever, was preoccupied with doctrinal feuding. The question of whether yellow fever was imported from abroad was hotly debated, as were the various treatments.

In his highly readable 1936 biography of Noah Webster, Harry Warfel reviews the pamphlet war and sparring newspaper articles that followed the outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia, as bloodletters argued with the vomit-inducers over who was more absurd. Webster criticized their manners, writing in American Minerva, “It has often been noticed by medical gentlemen that the yellow fever and plague have a most powerful effect on the brain. Is not this effect very visible in the violent contentions of the faculty in Philadelphia? Is not a partial delirium discernible in their writings and challenges?”

The seasonal timing of certain diseases, including yellow fever, gave credence to the view that weather, climate, and air were the essential bearers of disease. Writing of an outbreak in the summer of 1795 in Norfolk, Virginia, Doctors Taylor and Hansford remarked, “The air was evidently impregnated with putrid effluvia, arising from decayed substances of every sort, brought down upon the creeks and rivers by the floods of rain, and thence into the bason immediately before the town.”

Taylor and Hansford recommended purging and defended the animal diet that was criticized by others, noting, “Those whose circumstances permit them to purchase the best kind of meats and fish, certainly experience no inconvenience from these kinds of food.”

Webster wrote a preface and a closing summary, in which he mentioned his own experience with scarlet fever, “I was witness to it . . . in my own family: a severe catarrhal affection, accompanied with high fever, and a partial efflorescence of the skin about the throat and breast.” He argued that police should be used to wash streets, particularly in the cities where yellow fever had struck, and recommended the building of fever wards.

He thought it would be beneficial if the cause of yellow fever turned out to be local. Then city-dwellers might be persuaded to live more cleanly.

“If they can be convinced of this,” wrote Webster, “that sources of disease and death may be found among themselves created by their own negligence, it is a great point gained; for until they learn this, they will never attend to the means of preserving life and health. They will still wallow in filth, croud their cities with low dirty houses and narrow streets; neglect the use of bathing and washing; and live like savages, devouring, in hot seasons, undue quantities of animal food at their tables, and reeling home after midnight debauches.”

One can see in this passage, written before A Collection of Papers on the Subject of Bilious Fevers is underway, a major tension that still colors journalism on health and other subjects: This is the tension between reporting facts dispassionately and wanting to send the message the journalist and the public health establishment think people need to hear for their own good. Even as Webster stated publicly that he was not himself a physician, he looked to shape how the public received and reacted to information he had only begun to collect.

Nor was he satisfied afterward with the significant and well-received contribution of this one edited volume of medical papers. Webster’s career would consist of many fine collecting projects, carried out at his own expense. He began a history of American newspapers. He saw to the publication of other people’s letters and papers. His dictionary, like any dictionary, was a massive collecting project. But Webster was also a thinker, and the more he read about disease, the more he realized how little was known for certain.

In the spring of 1798, he began to do more research, visiting libraries in Philadelphia, New York, at Yale in New Haven, Connecticut, and Harvard in Cambridge, Massachusetts. According to Warfel, it took Webster 18 months to assemble his new book. Its full title was A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases; with the Principal Phenomena of the Physical World, which Precede and Accompany Them, and Observations Deduced from the Facts Stated.

Except for the word “brief,” the title of this two-volume work was apt. It was primarily a history of disease dating back to ancient times, taken down as notes, collated by year. Citing countless authors from the Greeks onward, Webster listed all the historical reports of disease he could find. It’s literally one bloody thing after another.

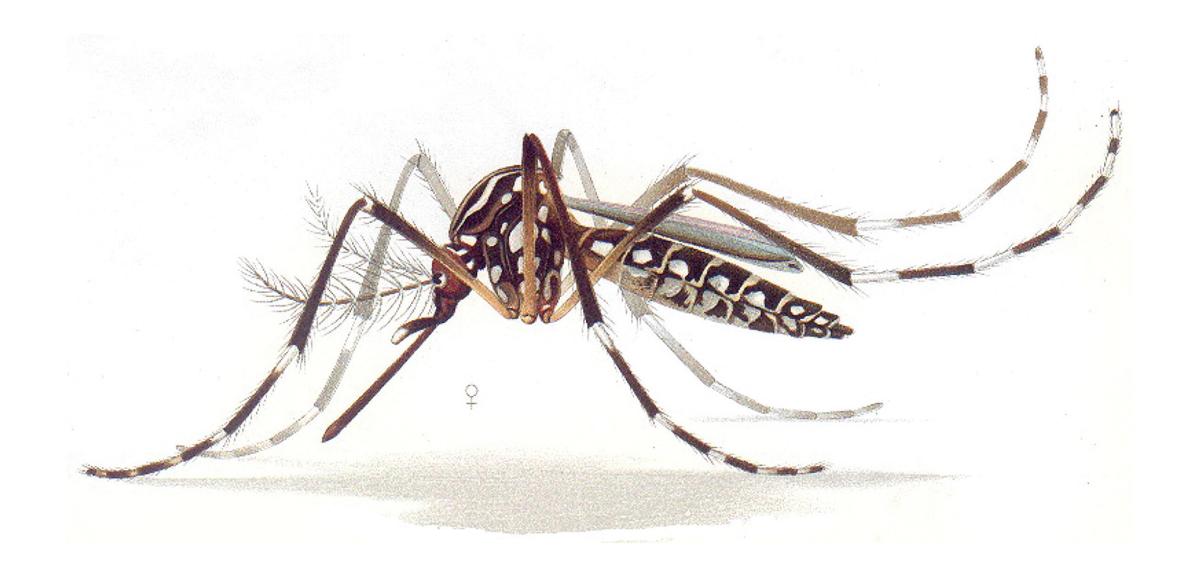

As such, A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases was an impressive distillation of historical data. Written half a century before the rise of germ theory and close to a hundred years before Walter Reed’s discovery that yellow fever was spread by mosquitoes, it filled a niche in American medical literature that helped it become a standard medical text of the nineteenth century. Along with the volume on bilious fevers, it earned Webster the title of founding epidemiologist.

What makes it especially hard to grapple with today is that, over the course of hundreds of pages, Webster more or less argues for an understanding of disease that not only connected many disparate diseases but also many disparate places and even disparate times. In want of a microscope, Webster had fashioned a kind of macroscope—informed by all the books in all the libraries he had ransacked for information—and concluded that the most promising path forward was to look for connections around the globe, linking events no modern writer would try to squish into the same narrative.

He briefly surveys the opinions of authors from Hippocrates forward on the causes of disease, finally calling them “weak, contradictory, absurd or inaccurate.” The idea that outbreaks of diseases were a form of divine vengeance he rejects with little comment. Then he begins to reveal his own thoughts, much of which were in line with theories of the time.

“As the most accurate observers of the operations of nature, have suggested the probability that pestilential epidemics are caused by some occult qualities in the air, or by vapor from the internal parts of the earth, or by planetary influence, it is absolutely necessary to enquire how far such suggestions are supported by facts. For this purpose, I shall note, any extraordinary occurrence or phenomena in the physical world, as earthquakes, eruptions of volcanoes, appearance of comets, violent tempests, unusual seasons, and other singular events and circumstances which may appear to be connected with pestilence.”

This leads time and again to passages in which Webster draws on the writings of various historians and medical authorities to suggest connections among distant phenomena:

In 1611 the plague carried off 200,000 inhabitants of Constantinople. It appears also in some other places. The summers of the three last years were very hot and dry.

In 1612 appeared a comet. A terrible tempest made great havoc with shipping—2000 dead bodies were found on the coast of England, and 1200 on that of Holland.

A plague in Constantinople, then a year later a comet and a tempest that kills thousands of sailors in Western Europe—what have they to do with each other?

Webster collected information in a “conjectural” spirit of tentatively exploring links, but everywhere one looks in his history is the same story. Calamities pile up as time shrinks and expands, while events separated by thousands of miles are brought within a semicolon of each other. “In 1677 . . . an earthquake was experienced in England; and in Charlestown, Massachusetts, raged the small-pox with the mortality of a plague.”

The most impressive aspect of Webster’s Brief History is the vast energy he poured into it. The number of sources he consulted appears to be in the hundreds. It also contains a great variety of first-person testimony from sea captains, small-town doctors, and health committee reports. He tallied meteorological data and used mortality tables to compare the rates of death during average years against years when disease struck. With journalistic skills and the use of public records, he brings together a great sum of information.

Warfel and others called Brief History the best history of disease written in the eighteenth century, and it may be so. But it is also a noticeably hasty performance. Webster is, by turns, obsessed with or utterly dismissive of the debate over importation. He presents himself as one who does not fall for old folk tales of monsters being born or of oxen that talk, but he proves credulous in other ways. In revisiting the story of the yellow fever outbreak, he seems newly converted to the idea that “uncommon flights of wild pigeons” in Maine had presaged the arrival of yellow fever in Philadelphia two years later.

The two-volume work often reads like some headlong research trip in which countless facts (famine in China, earthquakes in Europe, measles in the New World) are transcribed but never brought to order. On the other hand, without the right theory to hold facts together, any account would seem, at least in part, like wild guesswork. And, one wonders, is the actual truth that the Aedes aegypti mosquito spread yellow fever really any stranger than the imagined truth that a disturbance in the air did?

Webster had chosen well in throwing his energies into the fight against yellow fever, which during this decade claimed the lives of many thousands of Americans. Also, his method of library research, briskly collating notes from multiple authors, would serve him well when he began work on the American dictionary.

A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases became a standard reference work in nineteenth-century medical schools, but in the short run, the book subtracted from the author’s fortune. Printing the book cost Webster more than $700, and his enemies remained unimpressed.

While the editors of the Medical Repository wrote that “Mr. Webster has performed a great work,” William Currie, an eminent physician of the period thought otherwise. As Harlow Giles Unger quotes him in Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot, Currie wrote, “The doctrine of Mr. Webster on this subject, notwithstanding his elaborate researches, appears . . . to be as much the creature of the imagination as the tales of the fairies.”