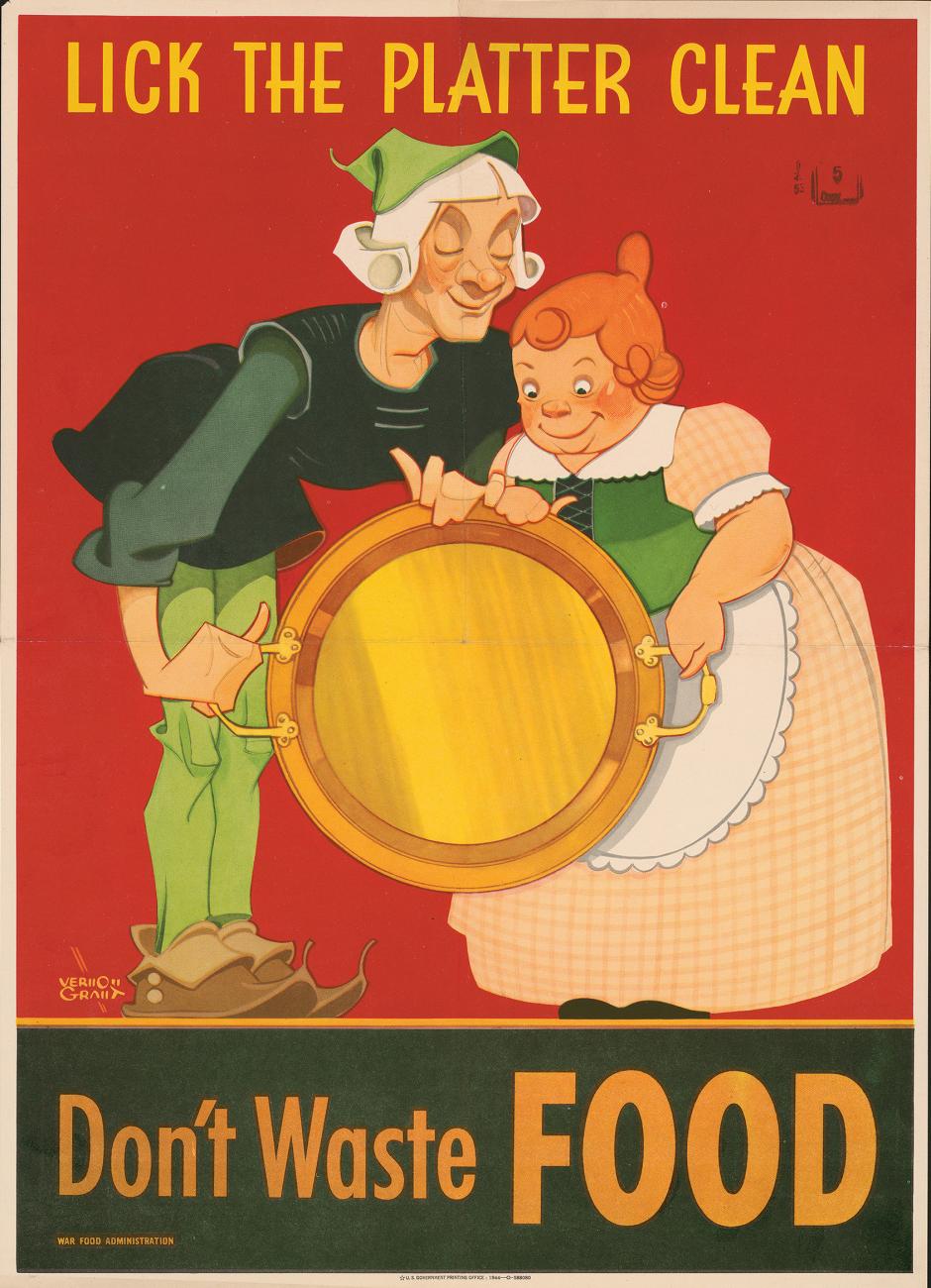

In 1942, as World War II ravaged much of the globe and those on the home front endured widespread rationing of basic necessities, author M.F.K. Fisher published How to Cook a Wolf, which offered advice on how to eat well in spite of the challenges.

Fisher’s book was so successful that in 1951, with the conflict long ended and the United States enjoying the fruits of postwar prosperity, she updated How to Cook a Wolf for another edition. It gave Fisher a chance to add a few thoughts about why, in the midst of hard times, it’s important to think about the finer points of the dinner table. By then, the world had moved on to a different problem— the dawn of the Cold War and nuclear weapons, which made the future of the very planet more tenuous. During such difficulties, were pronouncements on the subtleties of a French omelet or the requirements of an ideal gazpacho quite beside the point?

Fisher (1908–1992) didn’t think so. “I believe,” she told readers, “that one of the most dignified ways we are capable of, to assert and then reassert our dignity in the face of poverty and war’s fears and pains, is to nourish ourselves with all possible skill, delicacy, and ever-increasing enjoyment. And with our gastronomical growth will come, inevitably, knowledge and perception of a hundred other things, but mainly of ourselves. Then Fate, even tangled as it is with cold wars as well as hot, cannot harm us.”

Fisher’s basic argument—that good food can nourish our minds and souls as much as our bodies—might now seem self-evident to many Americans. That principle gained fresh currency during the lockdown days of the pandemic, as families stuck at home tried new recipes for solace and sought comfort in sharing meals. Thousands turned to baking, and online tutorials on making sourdough bread became something of a cultural meme.

With our seemingly intuitive sense that good food can be about more than a full stomach, the message of How to Cook a Wolf might now appear a given. Fisher emerged, however, as a writer at a time when food wasn’t nearly so central to the national imagination. The story of cookbook author and TV personality Julia Child, one recounted in the 2009 feature film Julie & Julia and a subsequent TV series and documentary, is a potent reminder that American cuisine tended to be bland in the middle of the twentieth century. Innovators such as Child, Fisher, and chef James Beard, who all came to know one another, helped shake things up.

“America was another country in the fifties,” culinary writer Ruth Reichl has pointed out in describing the nation’s eating habits. “Spaghetti came in cans. Cheese mainly meant Velveeta. Nobody had ever heard of cappuccino. Most fancy restaurants were serving something called Continental Cuisine, and the only Chinese dish anyone knew was chop suey.”

While Child and Beard taught Americans how to cook, Fisher, “on the other hand, believed ‘the first condition of learning how to eat is learning how to talk about it,’ and she wanted us to read about eating for sheer pleasure,” Reichl adds.

The pleasure of Fisher’s prose is the biggest reason, one gathers, why How to Cook a Wolf is still in print. Of course, as today’s households navigate the residual challenges of snarled supply chains and worries about inflation, any book that promises sound advice on dealing with scarcity is likely to get a second look.

Even so, many of Fisher’s 1940s recipes might sound dated to modern gourmands. Readers will perhaps wince a bit at the thought of Fisher’s sausage pie (or sardine pie), which includes biscuit mix and tomato sauce. Not even Fisher could get worked up about some of her offerings, such as war cake, a kind of heavy raisin bread in which spices can be used to cover the taste of an economical, if dubious, ingredient, bacon grease. “I am sure that I can live happily forever without tasting it again,” she confesses in a parenthetical aside.

As with many of Fisher’s books, How to Cook a Wolf is divided somewhat evenly between her recipes and her philosophical musings about food. Her commentaries are what make How to Cook a Wolf timeless. The book is really a literary rather than a culinary accomplishment—ultimately, more book than cook. Fisher’s cheekiness in telling readers how to make war cake and then warning them away from it is a small case in point. Much of the book is like that, as Fisher steps slightly offstage of her narrative and confesses a change of mind.

In one passage, for example, Fisher describes eating alone as something to be accepted as an occasional necessity rather than a pleasure, then dissents from herself in a bracketed addendum to the second edition: “I now disagree completely with this, and could and probably will write a whole book proving my present point, that solitary dining, no matter what the degree of hunger, can be good.”

This is even stranger because Fisher had already drawn that conclusion in “On Dining Alone,” an essay in her 1937 book of culinary pieces, Serve It Forth. These kinds of inconsistencies would be damning if Fisher weren’t so affable in admitting her intellectual caprices. Her work reminds us that many great essayists, such as Michel de Montaigne and Henry David Thoreau, are interesting precisely because they call the reader to watch them think things out in real time on the page, a process that can reveal vivid contradictions.

In doing so, Fisher invites us to think about what we already think. She’s skeptical of received wisdom, an iconoclast in the tradition of Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1942, as the urgencies of a global conflict inspired a general feeling about the primacy of American values, How to Cook a Wolf raised a subtle voice of dissent.

Fisher’s confidence on the page raised alarm bells. “When Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher began to write,” journalist Bill Moyers noted, “her publisher said, ‘Women don’t write this way,’ so she was told to use the initials MFK.”

Not that anyone would have been fooled for long about the woman behind the words. The title of How to Cook a Wolf was inspired by a poem by the pioneering feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Wolf at the Door.” Fisher suggested that when the wolf of adversity arrives at the doorstep, don’t run—just outsmart him and have him for dinner.

She encouraged her readers, presumably an audience at the time that was mostly women, to think for themselves, which was then something of a radical notion. Fisher chafed at the way that manufacturers had nudged consumers to make food choices not in their best interest, an argument that preceded the work of modern-day food activists such as Michael Pollan by decades.

“Why do we let our millers rob the wheat of all its goodness,” Fisher asked, “and then buy the wheat germ for one thousand times its value from our druggists so that our children may be strong and healthy?” She lamented that too many Americans “eat what is set before them, without thought, without comment, and, worst of all, without interest. The result is that our cuisine is often expensively repetitive: we eat what and how and when our parents ate, without thought of natural hungers.”

In England, even as battles between the Allied and Axis powers wore on, social commentators such as George Orwell and J. B. Priestley were urging readers to consider how postwar society might be reimagined. Fisher likewise argued that crisis should lead to reform. “Now, of all times in our history,” she wrote, “we should be using our minds as well as our hearts in order to survive, to live gracefully if we live at all. And people who fought to know better keep telling us to go on as our mothers did, when it should be obvious to the zaniest of us that something was wrong with that plan, gastronomically if not otherwise.”

That’s how much of How to Cook a Wolf unfolds; it’s not so much an instruction in how to cook but a continuing counsel in how to live.

Living deliberately is a key theme. There are no lavish meal plans in How to Cook a Wolf, but Fisher encourages readers to enjoy simple things with a renewed sense of wonder—another principle that achieved heightened attention during the darkest days of COVID-19.

Can’t afford a lot of coffee? Don’t extend the supply by using fewer grounds for weaker coffee, Fisher stresses. Instead, satisfy yourself with less coffee, savoring the cup. Chapters such as “How to Boil Water” and “How Not to Boil an Egg” compel household cooks to slow down, embracing an almost sacramental focus on preparing food.

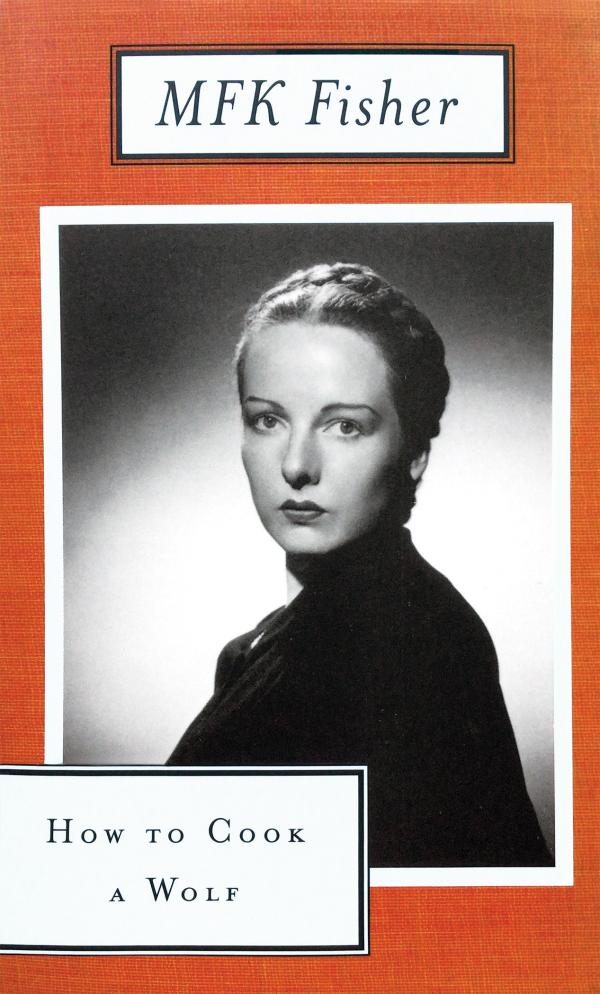

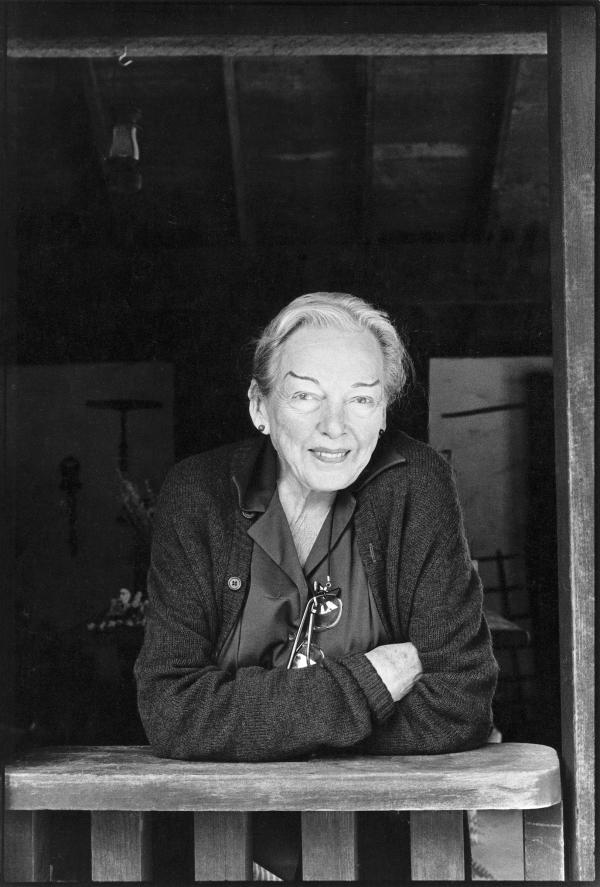

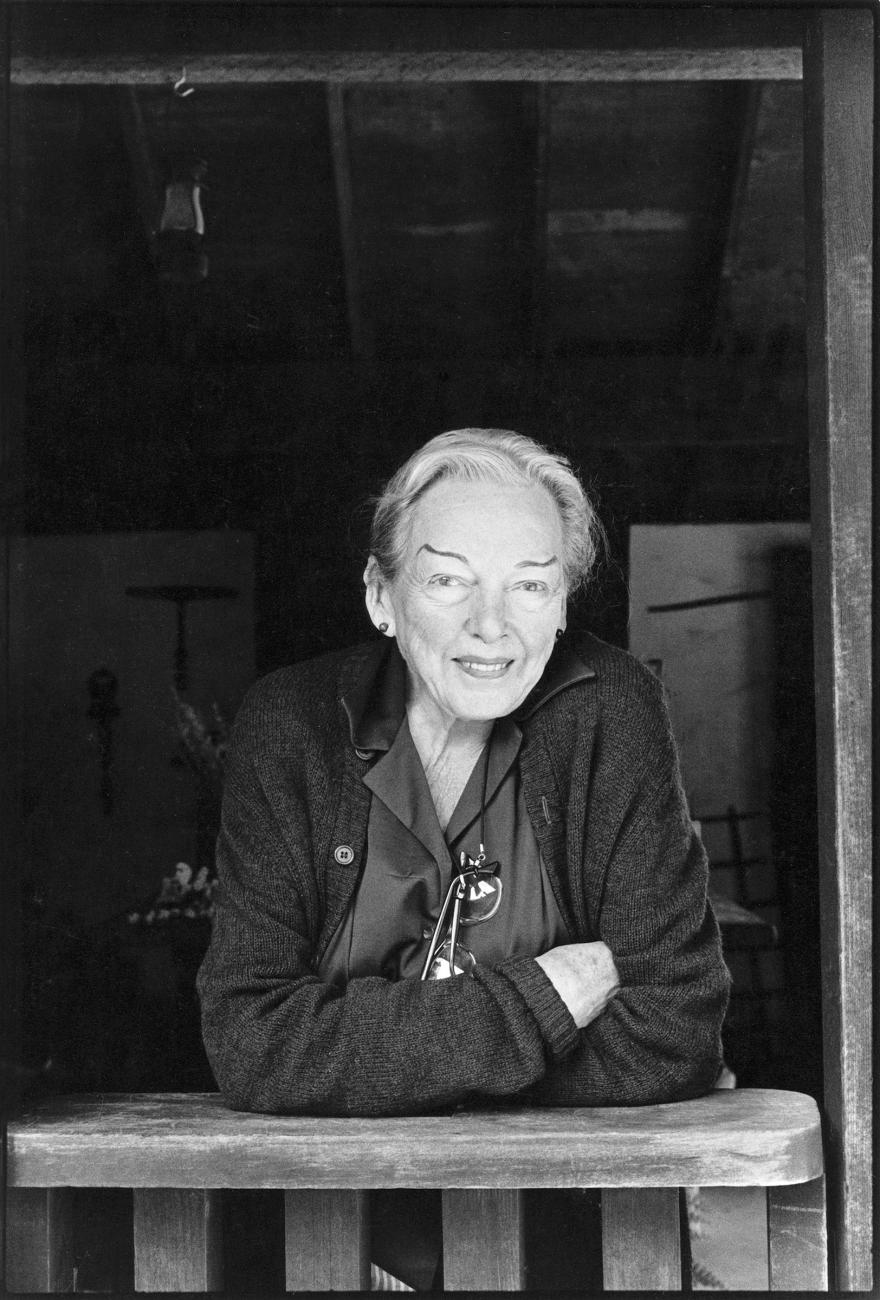

Fisher consistently sounds a note of confidence on the page, and when she was photographed, she usually looked confident, too. In the 1988 edition of How to Cook a Wolf from North Point Press, a striking black-and-white picture of Fisher taken by George Hurrell dominates the cover. She’s iconically beautiful—the composition looks like a publicity still from period Hollywood—but tellingly, Fisher isn’t smiling. She wasn’t a person, one gathers, who aspired to chummy familiarity with her audience. Fisher’s power as an artist drew from her ability to view the world at arm’s length, yielding observations born from critical distance.

Fisher’s sense of life as something best viewed just outside of the frame probably came naturally. She grew up in Whittier, California, as the daughter of the local newspaper publisher. The family was Episcopalian in a mostly Quaker town, and Fisher developed the abiding perspective of an outsider. Among Friends, Fisher’s 1970 childhood memoir, is like Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory in its elegant and sometimes elegiac evocation of an early twentieth century on the hinge of profound change. She recalls a time when airplanes were so rare that her teacher escorted the class outside to watch one fly by. “The big Jenny, made of wood and cloth, finally clattered over us, at about five hundred feet, and we all sent up a shrill cheer, and the pilot leaned out and waved to us,” Fisher writes. “It was a Moment, comparable perhaps to watching a man walk on the Moon, except more immediate.”

The scene underscores how distance was being radically compressed by progress, a development that enabled Fisher to more easily become a citizen of the world. She divided much of her adult life between the United States and France before settling for good back in California.

Just as Child and Beard did, Fisher drew on the insights from her time in France to inform her approach to food—and writing, too. In 1949, she published her translation of The Physiology of Taste, French gourmand Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s 1825 treatise on all things gastronomical. She looked to Brillat-Savarin’s prose as a model, hailing it as “a singularly straightforward and unornamented piece of prose to have been written in a flowery literary period.”

Fisher’s own prose attracted high praise. W. H. Auden matter-of-factly pronounced her “the best prose writer in America,” and critic Clifton Fadiman, not one who was easily impressed, counted himself an admirer, too. “The number of writers on food who are both artists and honest men or women is limited,” Fadiman wrote. “Among them must be placed M.F.K. Fisher.”

Honesty—or, at least, the impression of honesty—is a defining quality of How to Cook a Wolf and Fisher’s other books. In writing about food, she inevitably writes about herself—a fact she places at the heart of her 1943 work, The Gastronomical Me. “I tell about myself, and how I ate bread on a lasting hillside, or drank wine in a room now blown to bits,” she writes, “and it happens without my willing it that I am telling too about the people with me then, and their other deeper needs for love and happiness.”

Fisher once declared that the favorite book she had written was A Cordiall Water, a 1961 work about folk remedies that she completed while living in the French region of Aix-en-Provence. She said the book’s prose “seems to have a purity about it that I have long sensed in writers who are thinking in two languages.”

The search for simplicity was a recurring theme in Fisher’s work and in her life. Her final home in Glen Ellen, California, was a two-room house. But as with Ernest Hemingway, whose bare sentences unfolded against the backdrop of a complicated life, the ostensible economy of Fisher’s work ran parallel to a personal story that was anything but simple.

She was married three times and divorced twice. Her second husband ended his own life rather than endure the agony of chronic illness. She had romantic relationships with women, which was then taboo and created inevitable emotional turmoil. Fisher also suffered from depression and anxiety, and her autobiographical writings, for all their semblance of truth, have been criticized for indulging embellishments and fabrications. As biographer Joan Reardon has observed, Fisher “played fast and loose in her rendition of events.”

“If Fisher seems to advocate a sunny hedonism based on seizing whatever is pleasant in the moment’s offerings,” author Phillip Lopate noted, “it is always shadowed by a darker recognition of life’s limitations, unsatisfied hungers, and chagrins.”

Three decades after her death, Fisher endures as a bundle of contradictions, a writer we’ll never completely figure out. Perhaps that’s why she was drawn to food as an analog of her life. It, too, is an abiding mystery, and at her best, she summons readers to the peculiar alchemy that joins food and people, love and pleasure, the hunger for the bounty of the table, and the simple hunger for life.

“We must eat,” she told her readers. “If, in the face of that dread fact, we can find other nourishment, and tolerance and compassion for it, we’ll be no less full of human dignity.

“There is a communion of more than our bodies when bread is broken and wine drunk. And that is my answer, when people ask me: ‘Why do you write about hunger, and not wars or love?’”